Virtual Production: Are You Game? | Produced by the Academy's Science and Technology Council

Welcome, Academy members and the broader filmmaking community. As you all know, the genesis of filmmaking starts with an imaginative script that draws the map of where we, as filmmakers, need to go. But creatives of all types have to figure out how to take us there.

That's the magic of our collaborative art form and the beauty of the marriage between the arts and sciences. Today, we're here to invite you to explore how the most recent innovations in virtual production technologies and techniques can further this collaborative journey, as we provide a multidisciplinary view of how these new filmmaker tools can help evolve and expand your means of storytelling. I'm pleased to be joined for this presentation by key leaders in the virtual production arena who'll demonstrate notable advances in this technology and how they relate to most, if not all, of the Academy branches. Our presenters will share new work paradigms that will allow us to further globalize our talent pool, enhance our communication, and reduce our overall carbon footprint as we consider how best to allocate our ever more precious resources.

They'll also help us understand how we can continue to expand our creative capabilities while maintaining the safety of our cast and crews. I'm delighted we all have this time to learn more about these new technological advances so that we can collectively make informed choices as to how we create, how we connect, and how we continue to deliver compelling films that reflect the intent of the script from inception to screen. Before we introduce today's guests, we'd like to kick it off with a bit of behind-the-scenes magic that celebrates this ever-evolving and pioneering industry.

Wild, weird, wonderful-- the stuff of which movies are made, adventure to make you wonder if it's true, while your eyes convince you that it is truly the thrill of thrills. [MUSIC PLAYING] This is the way. Hello, colleagues. I'm Deborah Chow, a director on The Mandalorian and the upcoming Disney Plus series Obi-Wan Kenobi. One of the reasons I love both these projects is that I've always loved fantasy and sci-fi as they create new worlds of visual imagination, which we believe is real.

And that, for me, is the power of cinema, as you've just seen. For over 100 years, filmmakers relied on in-camera techniques, such as rear-screen projection, front-screen projection, and other more complex methods to merge pre-recorded material with on-set photography. There were several advantages to shooting this way. The footage was captured at the same time as principal photography, actors and key crafts people could work in context, and dailies contained all the elements that comprised a complete shot.

And while all of these aspects are clear advantages, there were also drawbacks, most notably, in regards to shooting limitations and image fidelity. Due to these challenges, many filmmakers transitioned from using projection techniques to blue and green screen photography, which allows for more camera freedom and higher-quality imagery but comes at the expense of not shooting the full scene on-set and leaving the final composite to post-production. Today, the tradition of in-camera work has come full circle and evolved into the dynamic and expansive world of virtual production.

With increased computing power, projection innovations, and recent technological breakthroughs, a new suite of tools have emerged that allow filmmakers to combine live action footage and computer graphics in real time. With these dramatically improved in-camera techniques, creatives can, once again, visualize their projects, direct the content, and make informed decisions in context. We all benefit from these advances as they allow us to put storytelling back in the hands of filmmakers earlier in the production process, thereby, accelerating the ability to establish the overall visual language of the film across disciplines.

There are a number of different ways this technology is utilized. Hence, our program is designed to give you a brief overview of the various forms of virtual production, demonstrate some of the most current practices, and share insights from a variety of branch members that we hope will inspire you to explore these new production methods as a means to expand your own creative capabilities. To join me as part of today's show, I'd like to welcome Ben Grossmann, the CEO of Magnopus and one of the key people in the industry, who has been working in the virtual production space for over a decade. Thank you, Deborah. So for the last century, we've primarily worked in the physical world.

Movie sets were the place to be if you wanted to know what the movie would look like. And there was no more important vantage point on a movie set than through the camera. Production used to be the place where we created, and post-production was where we edited and refined what we'd created. But when computer graphics became a filmmaker's tool, it came with a curse. We couldn't just create things digitally fast enough to include them in production, which gave birth to the phrase, "we'll add that in post." What did it cost? Everything.

Now, we might think of them better as physical production and digital production. A physical production often focuses on one single shot at a time, working in seconds, minutes, and occasionally, hours. Conversely, digital production or visual effects might work on thousands of shots at the same time for days, for months, for even years. Now, the resulting two groups of people have been separated by a calendar, making it even harder to create a consistent vision throughout the filmmaking process. How do we bridge that gap? Well, we're going to need to borrow an important piece of technology from our entertainment industry siblings, the games industry, which brings us to the term, "virtual production."

Now, we use physical filmmaking equipment, actors, sets, even locations with digital augmentation at the same time. Virtual production is the combination of the best of physical and digital production. So to talk more about how we meet in the middle, I'd like to welcome a film and game industry veteran and the Chief Technology Officer of Epic Games, Kim Libreri. Take it away, Kim. Computer graphics and feature films has been around since the early 1970s. In those early days, the work was severely limited by rendering times and the ability for artists to iterate on what they were creating.

While computer graphics brought exciting possibilities, meager computing power limited how fast their vision could be realized. In the early 1990s, CGI started to become an important part of the movie industry. At that time, the computer of choice was the Silicon Graphics workstation. These workstations enabled pre-rendered content to be incorporated into films such as Terminator 2 and Jurassic Park. As the visual standards and complexities increased, so did render times.

Individual frames could take hours, if not days, to be rendered. And in my embarrassing case, one frame took 144 hours to complete. I won't tell you which movie.

While this was happening in the feature film realm, the same type of hardware was driving innovation in a completely different industry, video games. The Nintendo 64, the first mass market console, offered many players their introduction to 3D gaming. It was a direct descendant of the Silicon Graphics workstations. But even though computer graphics and movies and video games shared many creative and technical inspirations, they stayed mostly on separate paths. However, film directors like Stanley Kubrick, the Wachowskis, James Cameron, and George Lucas were among the first to embrace what would eventually be known as CG previsualization.

My personal experience with early real-time visualization was in 1997, as we were planning the bullet time sequences on the first Matrix. In 2000, ILM used the first version of Unreal Engine to visualize the Rouge City for Steven Spielberg's film AI. During shooting, they were able to compose blue-screen shots of this virtual environment by combining the BBC's camera tracking system with an SGI Onyx powered system called Brainstorm.

This was the first use of real-time CGI, a simulcam, merging live action with CG elements on set to aid in framing and lighting during principal photography. Today, we call this virtual production. For the next decade, the film and games industries continued on their own paths with fairly limited crossover. But things began to change as game graphics started to look more and more realistic.

In 2002, Bob Zemeckis and his team at Sony Pictures Imageworks were early adopters of virtual production techniques, using Kaydara's Filmbox, soon to become Autodesk's MotionBuilder, to support a motion capture production, The Polar Express. Following closely behind, in 2005, James Cameron and his Lightstorm Entertainment team built upon this technology to create a directable interactive scene that resembled a video game. This became the methodology for Avatar.

Meanwhile, Jon Favreau and his team were pioneering virtual production techniques leveraging Unity's game engine for the 2016 Jungle Book and then later, for The Lion King. This allowed them to use traditional filmmaking techniques like dollies, cranes, and camera heads inside a virtual world, a further integration of filmmaking and gaming tools. These virtual production techniques came into sharp focus in prep for the first season of The Mandalorian.

As Jon Favreau assembled teams from ILM, Magnopus, Profile, and Epic Games to further advance the state of the art. With this, game engine technology has become central to bringing creative control back into the hands of filmmakers. And we're only just getting started. Thanks, Kim.

So as Kim just showed us, the foundational ingredient that we need for digital content to be real time is for the assets to be built in a game engine. And that's the secret. In virtual production, you're no longer separating the core creativity of filmmaking by months, which means that finally, digital production can work basically the same way that physical production always has, with very similar processes you're already familiar with. That means before we can shoot, we've got to build the things we're going to shoot, whether they're physical or digital.

In the future, it might likely be just one art department. But today, we have three, the Physical Art Department, which is responsible for the construction of physical sets and the augmentation of locations, the Digital Art Department, which is responsible for creating final quality digital assets to be used in visual effects, usually located at the visual effects companies, and the Virtual Art Department that fills in the middle and unites them both by creating real-time digital assets that can be used in virtual production. Ideally, all these art departments are separated only by tools and techniques. But they're strongly united under the vision of the production designer.

So let's look at how to create such beautiful assets. The Virtual Art Department priority is the best-looking assets that we can render in real time. And if you want to get them in camera as final shots, then they need to be really good. And if you're not trying to get them in camera, then they only need to be as good as required to influence the final creative execution. You might not finish a shot during virtual production, but you should have a pretty clear visual representation of what the finished product should look like while you're creating it live.

Now that creative buy in from the filmmakers on set can be critical. So here's a pro tip from experience. Just like any set, prop, or performance, the better they are executed, the more seriously people take them. And that means that the more likely they are to survive to the final cut. The more they look rough or incomplete, the more likely they are to get reimagined later. A Virtual Art Department can complement the work of a previous team.

And they'll build both the physical and the digital assets to assist a director in blocking scenes and a cinematographer in framing shots during virtual scouts. In a process called tech-vis, they can actually identify the parts of a scene that'll be built by the Physical Art Department and then the parts of a scene that will either be accomplished in physical production for live actions on set or by the visual effects artists later in post-production. So we can imagine virtual production as the spectrum between physical production and digital production. So let's explore some popular examples of virtual production techniques, starting with the simplest and working our way up. One, virtual production fundamentals that work anywhere.

Virtual cinematography, performance capture, traditional filmmaking interfaces to all CG material. You can use traditional live action cinematography equipment as an interface by building the assets in a real-time game engine. So your pre-vis team can employ virtual production techniques to bring a tactile, hands-on experience to the process and to make it more inclusive to creative collaborators who come from physical production.

Depending on the content, you may choose to capture your pre-vis with real actors through performance capture and use virtual cinematography with your DP. You can scout and block the scenes as you would in a physical production. But then, animate the scenes with your pre-vis team, then come back to the stage and shoot your coverage with the virtual cameras and render out your selects for editorial.

Two, virtual production techniques on a live action set. You can use real-time assets, real-time camera tracking, and real-time compositing to see what your shot will look like on the day while you're shooting it instead of months later. In this approach, you'll use blue or green screen to stand in for the parts of the frame that you'll replace later.

And then you'll record them through the camera using one of many available camera tracking systems so that we know where the camera is. Then we just render a video feed out of that real-time engine and use a real-time compositor to replace the blue and the green screen. Now, you've got a temp video clip that you can at least send to editorial that won't require a three-page list of notes about what's supposed to be added to that shot someday so that it makes sense. You might also have heard this technique referred to as simulcam because of the camera's ability to be working in both in the physical set but also in the virtual set. This allows filmmakers to see both of them composited together. You can also use real-time camera tracking and compositing to add a foreground computer-generated object to a live action plate.

And if you want to get fancy like the crew of Avatar did starting in 2005, you might performance-capture that character live, too. So you could either direct an actor on or off-camera, then stream that performance into a digital character, and then composite that digital character together with a live action plate at the same time. Third, virtual production stages. LED screens or projection for in-camera finals.

If you're ready to put a little more work into the assets and a lot more electricity into the stage, with the possibility of skipping some post-production altogether, then LED stages are the latest option to consider. This technique takes the real-time game engine environment and connects it to an array of LED panels. Then it uses the camera tracking information to render the perspective appropriate to the camera. Now, when you do this right, the walls and even the floor can just disappear to the audience. Getting the lighting to match between a foreground and a background is pretty key to a successful visual effects shot. And when we use an LED stage, we get the foreground and the background and the integration lighting to marry them together all at once.

And that interaction can be all the difference in maintaining the illusion. Now, this approach brings some added perks beyond just warming up a cold London stage on a winter day. And we all know the headache of a big location change in physical production. An LED stage can take an entire crew and its gear intact across the world or back in time in just a few minutes. So just imagine an entire day of shooting French reverses but without shooting French towers.

And if at any point you decide that the content on the screen isn't living up to what you hope to see in-theater well, with a button click, you can just switch that section to green screen and then keep using the other advantages from the rest of the stage, like lighting, creative contexts for actors. Maybe you tend to take the editorial for visual reference before you go pick up that safety shot. One of the key advantages of virtual production is getting creativity in the can today, rather than kicking that can down the road.

And the secret to success is buy-in from the filmmakers. Make sure each of your department heads is represented and has a voice and can get hands-on with what's being done and how it's being done. That ownership and confidence in the tools is going to increase the chances that when it's time to check the gate and move on, you won't be coming back in post-production to reimagine the shot. No innovation in filmmaking is possible without a director who's willing to embrace the unknown and take some risks in the hopes of achieving something truly great. And it takes integrity and patience to be a protective shield for the crew and their gear as they struggle to realize that vision. Jon Favreau has brought us highly-acclaimed films, such as Iron Man 1 and 2, Elf, and Chef.

Jon went on to push the virtual production envelope with the Jungle Book and The Lion King, as well as his latest cultural phenomenon, The Mandalorian. I've had the privilege of trying to fix broken equipment on numerous films while Jon waits patiently in the director's chair. And I think you'll enjoy his insights. Jon. Film is a medium that has always had a partnership between technology and storytelling.

From its earliest days, the foundation was a technical breakthrough, which was the moving image, was the film camera. And stories began to follow to explore what that camera could do. And the whole century that we've been dealing with the legacy of cinema has been a dance between innovation and filmmakers being inspired by those innovations, and then opening up the stories that they could tell as a result of those innovations, and then coming up against limitations, and then innovating their way out of those limitations by creating new tools. The legacy of cinema is relatively short.

A lot of the people who've innovated those new technical breakthroughs are still around and available to talk to. And I find that there's a tremendous generosity in our community, where, if you ask somebody how they did something or you want to use a set of tools that they innovated, that's part of why they do it is to pass those innovations down and then see how you build upon them. And so dealing with people like Jim Cameron and George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, these are people who came up with methods to be able to tell stories that were in their minds. You can't separate the technology from the content here because there's such an interplay that's required to understand, and that requires a lot of people who understand everything from budgets to technology to filmmaking, cinematography.

And all of these had to come together and coalesce in a way that made it something that could be done on time and on budget and ultimately, deliver a product that would be acceptable to the audience because they're the ultimate arbiters of any innovation. Because if you do something cool and they're not into it, that's not how movies work. I like to be inspired by things that I do in my day-to-day life or my travels or experiences that I have, but then I tend to work it into my writing.

And then the writing becomes something that then gets translated into a variety of images that are better served by being on a volume. I write for knowing what the tools that we have innovated can do and looking for new opportunities to innovate on top of what we had done already. It's ultimately process and workflow that determines whether or not these technologies are useful. And so by adopting certain workflows from cinema, live cinema and certain workflows from animation and certain workflows from gaming, there's so much overlap and evolution and cross-pollination now because the technologies are starting to-- there's a confluence. It used to be that there were certain things that were good for movies and certain things that were good for games. But those divisions are becoming harder and harder to draw distinctions, and it more becomes about narrative style.

Animation-- animation has always been steeped in technology at the time. And whether it's looking at the Pixar stuff or way back to cel animation, there's always a technological aspect to it. And you didn't get the luxury that you would on a live action film of filming a lot of stuff and then figuring it out in the editing room. And if you're wrong, you could cut it different ways. On a CG film, you render only what you're going to use because it's so expensive.

In animation, you would spend a lot of time sweat boxing a scene. You would have pencil sketches and put those story reels together and see how well they play and make sure your script is good. Make sure your jokes are funny. You do as much of that as you can before you ever touch a computer.

But this process requires a tremendous amount of work and planning in pre-production. In our case, we inherit what we did on Jungle Book and Lion King, which is we actually stage the action in virtual space. We create the sets as you would a video game level. The director, the cinematographer, the production designer, your crew, we put on headsets, and we go through the virtual sets, and we scout it as we would a location. As soon as gaming came on, you start to see a lot of consumer-facing technology associated with virtual reality, real-time rendering for gaming.

And we were able to use those to be able to make Lion King in the way that we did, using virtual reality and ultimately on The Mandalorian, using new faster video cards and video walls, LED screens, and game engine that was innovated for a very robust gaming community. We were able to use those in this industrial application for making film. Sometimes, it's good to go someplace.

Sometimes it's good to have the flexibility to be able to create an environment where you are. In the case of something like Star Wars, you could create worlds that don't exist, be on a Space Station one day and next day, we could be on the sands of Tatooine. I think sometimes, it's good to immerse yourself in an environment.

I don't know that I'd want to see a Terrence Malick film filmed on a volume. You know what I mean? I think that there are certain ones where the environment is a part of it, and you feel it or the actors feel it and then you feel it. The director is inspired by it. Jim Cameron was actually on the lot, too, working on Avatar.

And I remember him coming over to look at it. And it's so rewarding when somebody who's such a great innovator and somebody who I've really piggybacked off of all the work and research that he had done-- and he was very helpful with us with Jungle Book. And I'm working still with a lot of the same people who've overlap with his projects. So they've learned with him and brought that knowledge to my productions.

And I've learned from them. To have him see what we were doing and understand what we were using to solve similar problems to what he was trying to figure out as he's doing more Avatar films and always pushing the envelope on what you could achieve on camera with technology. And so to have him see it and appreciate and understand-- what's amazing, too, is you get somebody like him or like George Lucas walking on your set or Spielberg, and they immediately get it. Like you start to explain, and all of a sudden, they start asking you questions that are not the questions people normally ask. Like what's the limitations to this? How did you do that? How does that work? Could you do this with this? Could you do this for that? Oh, so you can't do this.

So how do you do that? They cut all the way through everything you've learned over the course of like a year or two in a five-minute conversation. And now they're asking you questions you can't answer. Cinema was the door that opened it all up, the movie screen, you know.

But now, we can create things. We could share things. We could experience the things differently.

And our brain can be introduced to imagery that we only could see in our imaginations or dream. But I think the screen is one small window into what our children's generation is going to experience. Once people have this available to them and as the price point comes down and Moore's law, everything gets faster. It's also going to get cheaper.

And as there's more adoption, more people will be using these tools, and then they're going to come up with cool things to do with them. And then everybody starts to benefit from those innovations. I mean, that's the ultimate experience because it's the communal experience between not just family members but different generations and the entire community coming together.

And I think there's something we pick up off of that, that is hard to measure, but it is very palpable. Up next is Rob Legato, a guy that I worked with on Jungle Book and Lion King, taught me a lot about this subject. One of the great innovators in this field, who's going to talk a little bit about consumer-facing virtual cinema products that are available for people to explore and experiment with. Hi, I'm Rob Legato.

I'm hosting this sort of mock session we're doing. And we're going to start with everybody introducing themselves and what they do. And we'll start with say, Andrew Jones. Hi, my name is Andrew Jones. And I'm a production designer.

I'm Caleb Deschanel. I'm a director of photography. My name is Amanda Serino, and I'm a set decorator. I'm Safari Sosebee. I am Virtual Art Department Supervisor at Happy Mushroom. So we're going to start with Andrew.

And what would be great is if we could start maybe with a blank set of this is what like a standard set would be. And then you'd start to add your magic to it to make it a personalized to the character. Rob, I'm just going to jump into VR to do this with Safari-- Sure, we're starting with-- now, maybe I should put my camera on. Safari, if you don't mind putting the furniture in without the other little props, it'd be great.

On my machine and Andrew's machine and Safari's machine, we have the ability to be in VR. And if you see this little thing - it says Safari on it. That means he's in VR. And then there's Andrew Jones, running around the set.

So you see little thing that says A. Jones on it. So he's actually in three-dimensional space walking around as if it's a real set. So I have a question, Rob. How can I get into the virtual space that you're in? Do I need to have a different setup with maybe borrow my grandson's headset, you know. You could go into VR, and you could walk around and do all the same things that Andrew's now doing.

So anybody can do it, and it's off-the-shelf items. But in other words, I could move around in that space, and I could say, oh, I'm in a good place to put the camera. Can you put the camera right where I am? Correct. OK. That's good. That's correct.

I mean, I think that's all I would need, you know. I want to point out to the viewers that right now, we're in a mode where it's not necessarily as photo real as it's going to be when it's eventually done, where we bake in all the lighting. We call it baking in. So baking is a term that you use.

It's the same as rendering? That's right. Andrew, do you want to talk about what you're doing? Yeah, of course. This environment reminds me of a place in New York that I used to know. I'm sort of creating a story around that, so I'm just adjusting things to match what I remember of that. Safari, is the dressing loaded in this scene? Yes, sir. First thing was we were going to try to make this wall have a brick texture opposite the windows.

That's one of the things that I remember about the environment I'm sort of riffing on here. And I found that that's a really successful graphic device in a volume, having architectural lines diminishing into the distance, parallel lines. What it does it just really sells the illusion of depth. Any sort of geometry that has gotten architectural lines really just makes the LED wall disappear. Where is the set deck? Safari, is that here? Oh, the extra stuff? Yeah.

Let me pull that up. OK. We're going to have a look at that with Amanda. Yep, I'm ready.

So I do have this overview environment, Amanda. The idea-- And Amanda, are you generally in VR when you do this? No. A lot of times, I will share Safari's screen. So I do know that it is shaky for viewers to watch, but it is a helpful tool. So Safari can drive around.

We would talk about bringing in five different things. We can put them in the environment. We can move them around. And for the most part, Safari does all that. And we just kind of work back and forth. And I think what we're trying to say is that Amanda's job would be identical to the job would be on a real set.

You actually have more options here because you control all of it. So once we pick a style of a sofa, we can change the color, the texture of the fabric, add a pattern. We were able to-- if we wanted to-- take that sofa and stretch it a little bit closer. If that seemed a little bit short, we can get it closer to the bookcase.

Safari, I don't know if you want to put the-- yeah, just one. And then stretch that out just a little bit. Oh, wow. And maybe you throw the pillow back in the corner. And then you can grab the blanket that's on the ottoman and bring that on over.

This checkered pattern one? Yep. The one you selected. That'd be perfect. Perfect. So it's kind of great that we have that ability to move things around. What shows up on the walls is an extension of what we're actually doing, rather than the main unit of what we're doing.

The first step for us is to build the whole place as we like it, as it tells the whole story, and then go in and find out where the action is going to go, where the camera is going to go. And then divide up the world into what's going to be built and what's going to be virtual. So that decision is going to be part of the blocking. I think what Andrew was saying about building the entire thing.

And then once you go into that space, saying, what needs to be real. And what determines what needs to be real? Is it something relating to the actors and their interaction with the-- A lot of it is down to the camera, honestly, Caleb, If you're placing a camera in relation to a performer, there's places where the virtual wall is going to work really well. And that's a major consideration. The distance between the camera and the actor, and the actor in the video wall. And it's flexible too. You can affect that.

You can change that around. For example, we could have a scene in the kitchen here and play that out with all of that area in the living room as a backdrop. And then we want to play another scene over the other end and you're going to use the same flooring. Perhaps you're going to use the same virtual environment as an extension, but in this case, the kitchen is going to be on the walls. And that can be done very quickly. You can swap from one to the other.

You're going to have, like Amanda was talking about, you're going to have dressing that exists both in the physical world and the virtual world. And so you're going to need to have both versions of a prop, for example, this table. If that table's going to have some action on it, we obviously need a physical one. If it's going to be in another scene in the background from the kitchen for example, Safari's team is going to have to scan that or build it into the game engine. Make it into a game asset and then it can exist in the background. But that's a really useful device.

Because when you have an asset which is appearing both in the real and the virtual world, it blurs that line. It sells the illusion, if you like. Most people who have never experienced this are afraid of it, because they feel like they don't know anything about this sort of technology and so that they no longer have a job. And I think our point is that your years of experience of the art of set decorating, which is the same and that you would be able to operate in the way you normally would. If I'm doing a virtual set, we can control the entire environment. What's green, what's actually tangible that we're shooting, and we can see it.

So you have a full knowledge of exactly what the entire set is going to be. Then we go in and we figure out what portion of that really is going to be where the action is, where the physical actors have to touch the items. So if someone's walking across it, if somebody's sitting on it, if someone's interacting with it, all that has to be real. So for a set decorator that job will never go away.

If an actor is dealing with it, it's practical, it's real, and then this is an extension to our job. And I've done several different projects. One is using a video screen, one was not.

And no point at any point did I feel that that could have been done without the proper people in place. Like for our department, you still needed a set decorator, you still needed the lead man, you still needed the crew to do. So I don't feel that this is definitely a tool to help make our jobs better, but it is certainly not a tool that is replacing anybody's position. We're ready for pre-light now.

OK. We had a pretty good daylight feel at one point. I really want some sunlight just pouring in there. Let me get the angle of the sun. There we go.

That's starting to get there. And if you were lighting this on stage, would you put up a 20K behind every window? Well, yeah. Chances are you wouldn't have as much room as you'd like to get-- you can't get back far enough to make it one light, so you probably would have put a light through each one of the doors.

I would think of it's on a normal sized stage. Yeah. Then what I would generally do, is have a big, large, soft light above that creating the ambience of the skylight coming through. What I always do when I do miniatures and used a one-point source being the sun, it would never really would hit everything you wanted to hit. So I'd always would go in with a little spotlight and just rake something.

And it looks pretty believable. Listen, you're really ultimately always creating the illusion of some kind of reality much more than you are. Well, reality isn't all that interesting or beautiful looking sometimes. Can you lower the sun a little bit? Lower, lower in the sky? Yes. There you go.

And maybe move it away from this a little bit so it comes more towards us a little bit. More backlit? Yeah, more backlit. There you go. Like right now the way the light is, you can say it's the middle of the day, you can say it's late in the day, you can say it's morning, you can say anything.

In the script it says, it's getting towards sunset. Or it says, the next scene is going to be nighttime. Yeah, it's approaching nighttime. What does the drama dictate as to what we're looking for? All those are the factors that have to do with lighting. And that's where the director of photography comes in. Because he interprets the script, and then the lighting and the framing of the shot specific to what you're trying to achieve.

And if it gets pre-lit by somebody who doesn't even have a script, they are just generically illuminating it more than lighting it. That's why it's important to have a director of photography actually dictate how it's done based on something. One of the keys, obviously, is to have as your right hand man in a live action movie and a digital movie as well, it's so important to have someone who's really, really good at lighting. And I was fortunate on the Lion King did have is Sam Maniscalco. We could blend my experiences with lighting live action with what he was used to lighting in a digital environment.

It's important to have that key relationship between you and your gaffer, just the way it is on a regular movie. And the same thing with a grip, we would use on Lion King, we had a real dolly on the set that was tied to the dolly that was in the 3D space. And all those things were really, really valuable collaborations. I'm going to go into VR here. My big experience with it is that when you could actually get into the set in 3D with the goggles, it makes it so much easier to deal with things. And it is really cool to be in VR in this set.

So now dolly-wise, when I go over the furniture or what do you think? If you just are in by this side of the coffee table and then just come straight back from there. So I'm on the kitchen side of the coffee table, right? Yeah. And then we can just look in towards the stairwell and then back ourselves up. Yeah, it really needs to come straight back from there. And then as it rounds the counter, it just needs to curve around.

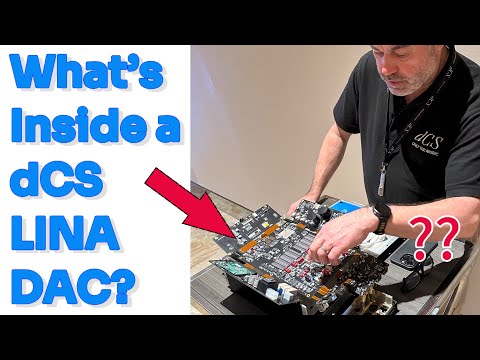

Yeah, it's pretty good. I think it's looking very good. So Safari let's send this to the LED stage. I'm Phillip Galler, co-founder of Lux Machina, a company that specializes in LED stage technology and operations. What you're seeing here is a direct delivery of content from Rob's basement tech-vis, to the Nant Studios LED stage in Segundo.

We're here today to show you some basic setups and how to implement this kind of technology for the production. Cave environments like this, are a great example of how all departments of production have to work together to really get the most out of working in a volume. There's a lot that goes into blending the physical and virtual together. And there's a lot of features that allow us to make creative decisions on the day. For example, this light shaft behind me can actually be moved around set in real time.

It's tools like this that allow us to make creative decisions that we can actually see in camera and realize completely. This gorge is a good example of how we can create endless magic hour in LED volume. The lighting mimics the real world, yet offers the opportunity to pause time and therefore, the ability to enhance storytelling. Every production will need to decide if this technique is right for them.

Thank you, Phillip. Now let's take a look at how some recent filmmakers are using LED volumes to create process shots. Cut. Ready, and action! LED volumes have expanded the way filmmakers can shoot a scene in pretty meaningful ways. Even without the benefit of real time camera tracking or a game engine, LED stages offer significant advantages over traditional projection techniques. With sharp imagery, controllable color temperature, and brightness, and removing the projection throw that requires a large stage.

LED screens can be configured in flat panels, curved panoramas with ceilings and floors, or many other shapes that are set might require. In addition, LED walls can be augmented with smaller, more portable LED screens for creative lighting as needed. That way, you get convincing reflections and interactive lighting on the vehicle, your talent, wherever you want the camera to be. And now to help get us back on track I'm going to turn this over to my colleague Rob Bredow, Chief Creative Officer at ILM who's assembled a panel to give us some further insights into the use of led tech for productions. Well, thank you so much for joining me here.

I'm Rob Bredow I'm the Chief Creative Officer at ILM, and I have with me an amazing panel who is actually working together right now on an LED stage shooting things in production. We are joined by Dave Klein, director of photography. Hey, Rob, thanks for having me. Andrew Jones, production designer.

Hey, Rob, glad to be here. Richard bluff, visual effects supervisor. Hi, Rob. And Janet Lewin, co-producer. Thank you.

So I just want to start by turning the clock back and Richard, let me throw this question to you. As a visual effects supervisor and someone who's responsible for the content on the walls and helping to put a lot of this together, how important was it for you and for Andrew Jones the production designer on the show that they bought into this technique and even thought about the show in the context of use of shooting a portion of it in this LED volume? I don't believe we would have achieved what we did without John and Dave driving this from the very beginning. We had some very conservative estimates as to how successful we thought this could be. A percentage of in-camera finals, percentage of scenes that we thought would lend itself to this technology, and all the way John was wanting to push the envelope and asking us to experiment. And even though we identified areas of concern, whether it was distance of the camera to the wall, distance of a wall to a physical set, trying to play on the same plane, John wanted to shoot those scenes regardless to see where the limitations were. And I think without John driving it from the very beginning and testing us all the way, I don't think we'd have learned anywhere near what we did.

So when it came around to season two, the gloves were off at that point. I remember John saying early on, let's not tap the brakes. Let's just go where this is going to take us and try to make it work. There's a lot of smart people. And the mantra right from the get go was, if it's a really great lighting volume and we're getting awesome reflections on our fully reflective character, we're in good shape right there.

If we're getting some certain shots in camera, fantastic. And the more, the merrier. Well Dave, we heard how important the DP is in this formula. And just from your perspective, getting involved in very early stages of prep and prepping one of these shows, what are the things that you like most about the control you have in shooting in the volume? And maybe, what are some of the challenges? You know what Rob, when I first took a load all the way from the prep stage to shooting, it's one of the first times that I've ever got a set to look exactly the way it was in your head and on the screen.

And because you've planned it for so long. And I get my great minds involved. I get the key grip, the gaffer, and I work with Andrew. And we work on how to light these sets that we've been looking at for a long time.

And it's really an exciting thing. That's the key about this methodology. Is that there's no need to reinterpret the intent of the key creatives like the DP, the filmmakers, the visual effects supervisor, production designer. Everybody's making a decision on the day. And that's either a final or the blueprint for the work.

Dave, can you talk a little bit about just the difference that you have to take into account in terms of your depth of field when you have an LED wall at a certain distance, but it's simulating content that is either much further back or perhaps sometimes even drawn a little bit closer to camera. Yeah, that's one of the things that gives away our magic trick. Because if you put a really wide lens in there and you're looking at mountains but the screen is only 20 feet away, you're not going to have the right depth of field.

And sometimes there are some tricks we can do to defocus that image. But for the most part, it doesn't do the same thing that our lenses do when you're out in a real environment. So it defocuses in a different way. And even if it looks good, your mind is telling you, that's not what I've been seeing for my entire life in the movies.

So we try and shrink the depth of field as much as possible. And also, the lenses we use. We're using Panavision Ultra Vista lenses that are vintage. They're are vintage glass and they have a lot of, let's say, character to them and very little depth of field.

So that's one of the huge advantages of shooting on anamorphic. Is that sometimes you can have a wide lens close to somebody and your background is physically 20 feet, but it should be a mile and you get away with it. It clearly means, that your visual effects work that used to be happening in post is going to be earlier into the process. Does it affect a lot of other departments? Does it affect a lot of other things about the schedule? It does.

We're leveraging as much as we possibly can in a virtual setting. So sending teams out to location to get photogrammetry as opposed to a company move, kitbashing from miniatures and elements that are in our digital backlog to create that very organic Star Wars feel even though it's with a very high tech methodology. John and Dave and all the filmmakers, they fully commit to the designs that Andrew and Doug come up with. So once it leaves Andrew's department and moves into visual effects, as far as we're concerned, we are executing exactly what Andrew has handed over. Because that's what the filmmakers want to see.

The point is that whatever we end up with on the screen the day that we're shooting, the filmmakers and Jon Favreau in particular, is fully committed. That's it. That's the final.

And that's incredibly refreshing. Well, given that you are some of the most experienced experts in this space, if somebody was diving into a show like this for the first time or trying to shoot on a volume for the first time, what's one piece of advice, something you've learned maybe the hard way that you could pass along to somebody from any department? Andrew, can I start with you? I really think that simplicity is a good place to start. I've seen some sets that have been conceived right up the bat that are really complicated, involved sets with a lot of moving parts. And you can make those work.

But if you want to have a lot of success and start to learn the process, just take some simple ones. That was the most successful ones for us on season one, and got us in gear for everything that came. That's great. Now, Janet. I would say, be mindful of this paradigm shift that we talked about. For filmmakers who want to embrace this methodology, it means approving those designs early.

That's where you get the big win. Is to walk away after the shoot day and have those in-camera finals or the blueprints for post-production work. That's great. And Dave. My one piece of advice would be to work with Andrew, Richard, and Janet.

Because without the team that I've met here, I wouldn't know how to approach shooting a volume. Especially, I've been scouting virtually. This is the first show I've ever been on, where I can do a lot of my prep virtually. And in season two, we were virtual Scouting not only the volume loads, but also the practical sets that Andrew was going to build and put on stage.

It was more designed to look at the volume loads, and the crossover was putting practical sets in there. So my advice would be, to have a virtual art department that's very experienced to help out your other creatives. That's great. Worth mentioning there too, that you are able to go in and light the sets, and lens the sets, and get your head around the set early on in the virtual world. And also just another point with that, we were all able to go and collectively virtually scout sets in VR. You don't have to jump in a van and go someplace.

But other than that, it's very similar to actually doing a scout. That's been a bit of a benefit, I think, is getting everybody in there early to look around and get familiar with it. And Richard, I want to end with you.

One bit of advice for someone jumping into this for the first time? I think the word's collaboration. It's hard to think of other situations in filmmaking that brings so many different departments together. And it's a great leveler, everybody gets to contribute, everybody gets to see their work on the screen.

And affect what's on that screen, whether it's in prep and on the day. And so as a result, I think everybody has to buy into it. Everybody needs to want to do it this way. Because this isn't a visual effects tool, this is an approach and design tool, or a deep piece tool, it's a filmmaking tool. And I think everybody has to get behind it, and want to push the technology forward and understand it.

And hopefully, have a good time. Now, that's great. Thank you so much for that.

And thank you to Richard, and Janet, and Andrew, and Dave for joining us and sharing your expertise and everything you've been learning in working in these kind of volumes. Thank you very much. And now we'd like to welcome back Jon Favreau, to open up the conversation to other branch members in the Academy. It is now my pleasure to introduce you to Dana Glauberman, Carl Weathers, and Jonah Nolan to discuss emerging technologies like the LED wall, the volume, and virtual production and their experiences with them as filmmakers. Jonah, I know we alternate between asking each other questions about how the other dealt with certain challenges that we were about to deal with.

I know the volume in the video wall and those techniques that we were exploring or doing research to get ready to explore on the Mandalorian. I think that was the last thing we bounced around. We have one amazing dinner in particular, when it comes to the volume.

When you explained what you were going to try to do, I said that's the dream. That's the dream. If you can pull it off, then everyone gets to benefit from a whole new set of tools. And you did. And you were so generous, you let me and my team come down and take a look at what you were building. I did not realize quite how ambitious.

[LAUGHTER] We were talking about set extensions. You created a whole universe there. Yeah, it's interesting because we're all dealing with the same problems, and each of us solve different aspects of it and then learn from each other. And so your inroad to it was through conversations and having discussions about it from separate experiences. With Carl, it was a different inroad.

Because Carl, you and I worked together. And, well, we knew each other from the DGA for many, many years just as colleagues and friends. And then eventually, it was to see if you would do me the honor of doing a small role that ended up turning into a big role on the first season of The Mandalorian.

And then you jumped into the directing seat and just crushed it right out of the gate. A part of what I enjoyed so much while working with you, is that there was a hesitance at first when you made that transition. Because you don't pride yourself on being a technologically cutting-edge person in day to day life, right? Very good, Jon, yes. And you're not a person who strikes me as being intimidated that often by anything but this was something where I saw you brought your lunch pail with you every day. And you wanted to learn every single thing you could before you stepped onto the set. And then immediately, because the technology is so young and is transitioning so quickly, now what I'm really liking is that you're becoming one of the handful of people who have expertise in this and experience in it.

And now you're being asked to sit on panels and explain your experience and pass that knowledge down to them. Which I think is really a testament to the technicians that have put this together and made it so user friendly, so that you could transition without ever feeling a bump in the road. And understanding it so intuitively that you're able then to use those tools to your advantage in storytelling. So you went from somebody who was hesitant and an early adopter, to somebody who became one of the foremost people in your field when it comes to this technology. Well, I was fortunate enough to have a mentor, to have a creator, to have a person who really understands technology. And I had listened to you, as you said, for several years in those DGA meetings.

And you weren't just about the technology even though that's what we're talking about, but you were about so many other aspects of filmmaking. And to have a place where you're secure so that you know, Oh, I can go to Jon and ask Jon. If he can't tell me right now, he'll have an answer for me before I get a chance to exhale.

What did I have to be afraid of? The only thing that I was afraid of was that, I wouldn't live up to what was there, and what was available at how good the previous episodes had been. So looking at the technology, come on man, throw more at me. I'm just dealing with technology that has been created. And how many other directors have dealt with it? So I always felt comfortable.

But on top of that, you had such great technicians. From our DPs, to our first. I'll give you an example. I never told you this, but I remember being on the stage for one of the first times and I can't remember who said it, I think it was one of our first. All I remember is hearing something about the volume. Jon, I didn't know what the hell she was talking about.

[LAUGHTER] I had no clue. And a second or third day I went, Oh, the volume. So there's so much in technology that doesn't necessarily relate to the experience. But if you have enough really good people-- Yeah. --you'll get it. You'll get it.

It's often nomenclature. Because you had so much experience of being there and working with it already. And so there wasn't really as much to learn as you thought going into it, because you already knew how to direct and you already had been on the set with that crew. And that crew already respected you and liked you. And so it was a very shallow learning curve. If you hadn't noticed, I like to have people around me who were more experienced than I am.

And that's how I got to where I am now, is just by being around really smart experienced people. With you Dana, when we had reached out to you to work with us on The Mandalorian, you were involved from the very beginning. When we were first in VR, you were working with our animatics, with our pre-vis with our VCam, the virtual cinema techniques that Carl was alluding to through production, and then in post-production as well. At any point, you can weigh in on it as a collaborator. So it's a big question, but what was the process like? How did you find it different? Did you find it limiting? Did you find it empowering? What's your take as somebody who has a wealth of experience in the traditional cinematic form? I had never heard of the volume before.

So when you explained to me what it was, I was just blown away by it. The fact that you can shoot a sunset all day long without having to worry about light, losing the sun, lighting changes and whatnot. It's quite empowering and it's very exciting for any production moving forward. You were not just learning a new technology, but you're also teaching other people.

What was that dynamic like? How was that experience different from what you're used to? It's all a collaboration. And I love teaching people about storytelling and some of the techniques that I have, in terms of making things look seamless on the screen and cut together really nicely. So my experience with it is quite empowering. The technology of the volume is not really what I understand but doing what I do as editing, and teaching people, and taking people under my wing is what I love the most.

How about with regards to the footage that you were seeing, or the techniques we were using to film it using these newer technologies? This is the first time that I have gone through and actually cut pre-vis. And I was a little bit nervous about working with it at first, but it really allowed me to learn what the directors are going for, and really learn the story that much more. Because to have the conversations with the whole production team in terms of wanting to get a different angle, or wanting to get a close up of something that wasn't necessarily planned for, just being involved in the conversation so much earlier than what we normally are is really exciting and really helpful.

And it just makes you feel more a part of the collaboration and a part of the process. It's interesting because I think that the thing you're identifying, might make the biggest difference more so than the technology itself. Because the technology demands so much pre-production. We ended up inheriting a lot of the workflow of animation.

And an animation, the editor's involved very early, the directors-- You have pods of creatives that see this production through for many years, and have a voice in every step of the process. Because the actual production or the rendering of it is so cost prohibitive, that you have to be very sure it's measured twice, cut once. But I'll go back to you Jonah, Dana and Carl both said that they don't see themselves as technologists first. But from my conversations with you, you really are the leader, one of the leaders of your field as far as tech goes because you just enjoy it. And it just is one of your interests. And I think it's overlapped with the filmmaking experiences that you've had up to this point.

As a writer primarily, that was your first. That's the first of your many hyphenates. As the writer, how do you see technology as informing your creative process? Do you just tell a story as you would, or do you take into account the techniques you might be using? I spent the first 10 years of my career writing movies with and for my brother. And so he would handle the directing, producing aspect of things and I would handle the writing and the things and just working in the movie business. What I brought to the table with Chris, was that I didn't know or care how he was going to have to do it.

So I would come in and say, no, the right thing for this sequence is it should be a bunch of ninjas stealing something off an oil tanker. I remember the look on his face when I submitted the pages and he goes, Oh, OK. All right. Let's figure out how to do it. Yes this is the right moment, but we already budgeted it. And how are we going to do an oil tanker? Then you get into it, and figure it out.

So I always try to keep that part, you can see the writer as a inner child. Slightly naive. I don't know how you're going to do this? And try to keep that switch flipped when we're writing. And then when it comes to the directing, in television I got a crash course in actually now having to be responsible for all the nonsense on the page. But that's what I think is so fun about where all these technologies are going. And what I saw when I first came down to see, to visit you on the set of The Mandalorian is its magic.

We've gone through this 25 year period where there's a lot of imagination that the actors and the crew members and everyone has had to do. I remember getting a tour of Leavesden where I think you've worked there. I've worked there.

And it was the great Harry Potter factory for years. Warner's turned it into a museum. And I was getting shown around and the beautiful practical sets.

And then we got to the Quidditch set. And I was really excited for the Quidditch set. And it was so disappointing. It was a big green room, with a green jib arm, with a broomstick. And he went, Oh. And obviously, terrific actors, terrific filmmakers have been making terrific films with these technologies.

But you go all the way back to the Lumiere brothers and the beginning of film, where you had to figure out how to get it in the camera. You really couldn't fix it in post, you couldn't figure in those things out. And what I love about the technology, is the volume technologies. As you were saying, breaking up this rigid hierarchy or linear filmmaking where it's prep, its production, post-production, the vis effects vender has never talked to the production designer.

And with these sets of technologies, one, you get that magic on set, which is so exciting. Yes, the actors can do it without it, but it's so much more exciting for everyone when you can see the reality of it. But also having everyone editorial, vis effects, production, art department, everyone there building it together, that's an amazing... And it's hard to make any case that that's not an improvement in the way things. It's interesting because Carl and I know your brother from the DGA.

And although you've collaborated a lot with him, hearing you too speak about technology there's definitely a different take on it. Because Chris is a bit of a purist when it comes to projection, photochemical. Not that he's not a master with visual effects because whenever he dips his toe into it, it's not it's not from lack of experience with it or mastery of it. To me when I think of Dunkirk compared to what we do on The Mandalorian, it's opposite ends of the spectrum. Hopefully, with a common respect for the history of cinema and the images and the audience. But it's a very different technique when I see him submerging a plane in the water on a real location with IMAX camera with film running through it.

Yeah. but yet I think we're all colleagues and there's a lot of mutual respect. Which I think people don't fully understand is that we can have different tastes, but we're always talking to each other and comparing notes. And Spielberg is interesting because he's the one who goes from one to the other.

So there's really room for all different types of exploration, experimentation, and collaboration. It was amazing also with the actors who were excited by it, and who appreciate it, and who were confused by it. A little shocked, exactly.

To me, when I got the biggest kick out of is Werner Herzog, who was there. And he was the one who literally moved a boat. [LAUGHTER] Over the mountain.

Yes! yes! Across the country, across a country! A continent! You could have shot that thing in a week here. He's done stuff with 3D drones, shooting on iPhones, he is not afraid of technology. But he's a consummate storyteller.

The other guy who was like that was Robert Rodriguez, who we've been working with. You see him because he was the guy I picked his brain about Sin City. I'm like, how did you do this? He's always found a way to do things efficiently. When he's using techniques that would require normally bigger, more heavily financed productions and you watch a person like him working on it, and their minds going-- And what they're doing with it, the version they're all going to come up with, that's more efficient and better and cheaper. And that's part of the fun too.

As we introduce these other filmmakers. And a lot of filmmakers I think, have gone off to work with this technology. And you Jonah, you've worked with a version of th

2021-10-23 13:54