TOFS-17 Joseph M. Cheer - After the pandemic: Tourism policy and planning and 'building back better’

So good evening, colleagues. Welcome to the number 17 Tourism Online Forum Series in May 2023. This series is hosted by the Center for Advance Tourism Research (CATS) at Hokkaido University. This is your host.

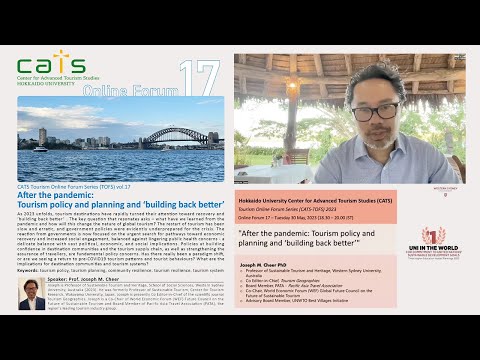

My Chinese name is Qu Meng, and my Japanese name is Kyo Mou. In English world. My. My name. Everybody call me Mo. So today we are very honored to have Professor Joseph Cheer to share his recent research. The title is After the Pandemic Tourism Policy and Planning and Building Back Better. So Joseph is a professor of sustainable tourism and printed in the School of Social Sciences at Western Sydney University in Australia.

Before he was a former professor of Sustainable Tourism Center for Tourism Research at Wakayama University in Japan. And Professor Joseph has also presented the world famous tourism journal editor in chief of the Journal of Tourism Geography. So he is also a co-chair of the World Economic Forum and a Council on the Future of Sustainable Tourism.

He's also a board member of Pacific Asian Travel Association. Also from the industry side, the region's leading tourism industry group. So so today his also bring a lot of a very interesting research question. One of the key research question would be what have we learned from the pandemic and how will this change the nature of global tourism after the pandemic? And furthermore, is also really see if this is the new paradigm shift or we are seeing a return to the pre-covid-19 tourism patterns and tourist behaviors.

And what are the implications for destination, community and a tourism system. So Professor Joseph is currently in the island nation of one of tours. So if you're looking at a map is between Solomon Island and Fiji.

So since there was no stable internet connection and the Wi-Fi single in the area. So here's a very kind, popular recorded lecture. It takes a run of 45 minutes, but he will join our Q&A session after 7:00 in Japan Standard Time. So if our audience have any questions, please leave your questions. And the comments to Professor Joseph in the meeting chat box.

And since many audience were able to attend tonight's seminar. So we will upload our recording on YouTube channel. Please note is that this online lecture will be recorded and upload to the forthcoming YouTube channel of Center for Advanced Tourism Research. So now let's invite Professor Joseph to share his lecture and share my screen. Okay.

Good afternoon, everybody. My name is Professor Joseph Cheer. I'm a professor of sustainable tourism at Western Sydney University in Australia.

Thank you to Dr. to Associate Professor Chou for inviting me to present this lecture today as I am traveling. I wasn't able to provide this lecture from my office in Sydney, but instead I'm recording this lecture in Vanuatu, which is an island in the South Pacific island country in the South Pacific. Now, the reason I'm recording it is because Wi-Fi is generally slow and unreliable and it drops out every now and then. So rather than do this lecture live, I am doing it via a recording and hopefully I can join you for the Q&A session later on this afternoon.

So again, thank you to Hokkaido University and the Center for Advanced Tourism Studies for inviting me as well as being a professor here at Western Sydney University where I started on the 1st of March. I was previously Professor of sustainable Tourism at the Center for Tourism Research, working on the University in Japan. I am also a board member of the Pacific Asia Travel Association, the region's largest travel association, and I am the co-chair of the World Economic Forum's Global Future Council for the Future of Sustainable Tourism.

So with that said, where I am today and I think where I am today gives you a good example of the very issues that we talk about in tourism. And I will explain a little bit more about the country that I am in and why I am here and how the research is relevant to the work we are doing now. While I am doing this talk, you may have a plane fly overhead, you may have dogs barking, you may have birds, and you may have tourists and staff members walking behind me. So please bear with all of that. This is being recorded live in a hotel in Port Vila, which is the capital of Vanuatu. So let me share my screen with you first.

I've got some slides that I prepared specifically for this lecture, and here are my slides. So when I was talking to Hokkaido University, a Center for Advanced Tourism studies, about this lecture, I thought it might be good to talk about where we see ourselves after the pandemic and talk about tourism policy and planning and this whole idea of building back better as I said, you will be interrupted by some background music. And here they have some very giant lizards called geckos, and they make a lot of noise every now and then. It's currently about 5 p.m.

in the evening, so within the next hour it'll be getting dark, so I better hurry and get this lecture done. So with that said, this will be the focus of my my lecture today. So what I wanted to do first is talk about some of the major issues when it comes to the question of sustainable tourism. So I will now go to full screen. So this idea of sustainable tourism is considered a paradox, right? And the question, can tourism ever be sustainable? Needs to be asked. Because when we talk about international tourism in particular, we're talking about people flying on planes and the issue of carbon consumption and climate change is a big factor in this discussion on sustainable tourism.

So how can tourism ever be sustainable if this is the business model it operates on? Also, there is domestic tourism and very often the more tourism we engage in, the more carbon we use. And therefore how can tourism be sustainable? If tourism involves highly consumptive habits. But I'll come back to this question about the growth paradox and whether tourism can be sustainable. To give you some some ideas of where I have been and the work that I've done, this is some of the work that I've done so far.

We've talked it when we talk about sustainable tourism, we've talked about tourism resilience, adapting to environmental change and adapting to social, political and economic change. For example, where I am today, about a month or two ago, we had two cyclones in a row. It destroyed much of the the the tourism industry up to here, and it caused the industry to have to rebuild again. Of course, what we see is that, you know, following COVID where there was a major hit, the cyclones have had a big disruption to much of the infrastructure, but not a not a totally permanent impact. There are hotels starting to open up again and tourists are starting to come back.

But of course, there are operating issues that are very difficult to resolve overnight. The book over tourism is something we've talked about in the research I've done with colleagues a lot. To what extent do we understand the limits of tourism growth? And around the world, in the age of tourism and this is before COVID, we noticed that many destinations around the world were suffering from tourism, added, It either gone out of control or tourism that no longer had the best interests of the local people at heart.

But I think it's important that when we talk about tourism, we look at the supply chain, and this is why we did some work. On looking at the incidence of modern day slavery and orphanage tourism. But of course, whenever we go to cheap destinations, whether it be in countries in the global south, such as in Southeast Asia, Southern Asia, Africa or Latin America, we often find that tourism is cheap. But when tourism is cheap relative to what we earn in the countries developed countries, if we come from Australia and Japan, the question must be raised why is this cheap? And who is paying for this to be cheap? I'm also worried about global tourism and COVID 19. Global tourism has had a significant impact on tourism, as we all know.

The whole world came to a stop, but we also know the global tourism has changed. Some things in tourism, especially visitor patterns. We see that now it's less likely that people will fly long haul flights, let's say, from Australia to Iceland or from Japan to Latin America. And instead people are flying short and medium haul destinations, which is very close to their countries of origin. We also talk about the growth in tourism in the Asian century. We see that economic growth in Asia is vastly outstripped, economic growth elsewhere and we can't miss it.

We can't under acknowledge the impact that economic growth has with tourism. And then we write about island scapes and tourism in my latest book, where, although we love going to islands, to some degree, island tourism can be the most unsustainable form of tourism. Because we think about islands, most of the things are taken to the islands in terms of fuel supplies and everything else. Is it necessarily the most sustainable form of tourism is something we ask in this book. So that's my general introduction to the work that I've done.

Now I want to present to you some notes from the field where I am today before we go on to discuss other things. So, I mean, the country of 1.2, which is in the Pacific Islands, you can see on the left of the screen Australia and the red circle is where I am at the moment in the capital city, Port Vila. We see the Pacific is a vast area made, made up largely of ocean, and we see that within this ocean lies a lot of small island developing countries. And within many of these countries, tourism is probably the most important industry for their economies over the last couple of decades. Japan is further north, probably another 8 hours or so from Port Vila.

If you flew in a plane directly. So tourism in Vanuatu, a small island, developing states, is largely made up of leisure tourists and cruise tourists here. The questions about whether tourism is contributing to the development or not is a very big question. Right?

To what extent are the local people benefiting from tourism? As you can imagine, the COVID pandemic had a major impact on tourism here. And if we are to do what many research is saying, stop flying, we will see that small island countries such as Manawatu will struggle for their livelihoods. Especially tourism, is one of the major forms of livelihood. We see other destinations around Vanuatu, like Fiji, like New Caledonia, like Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea. So as a small island, developing states, this these countries are very vulnerable to climate change and they are at the forefront of the climate change movement where as sea levels rise, many small, low lying island countries find themselves inundated with the rising water that comes in.

So while tourism here is seen as a mechanism for development to help the country become more prosperous and developed, it also contains a large number of problems that prevent it, that prevent tourism from achieving its aims to be a vehicle for development. In a paper written by the UN Center for Trade and Development, they talk about the prospects for a post-pandemic tourism and economic recovery in Vanuatu. This is a question that many, many countries are asking themselves. What does the pandemic mean for our tourism industry? Will we get it back or not? As we speak here in Vanuatu, recovery to 100% of where tourism was before the pandemic has not happened yet. We see that the airline is suffering from under resourcing. We see that the government has other priorities too, to deal with crisis, to deal with the two cyclones that they had recently.

So how can we say that tourism will be a vehicle for recovery when some of the most basic needs in the country are not being met yet? As as the the next slide shows here, no one was prepared for the crisis and that and that as well as the peak the economic crisis from the pandemic slowdown, we see the ongoing feeling, the ongoing impacts of a climate crisis in terms of water, in terms of more incidents of extreme weather events like cyclones. And how can small island countries that rely on tourism deal with the vulnerabilities that they have and resilient to a lot of the climate change effects that are impacting the tourism industry? And at the same time, we see, according to some of the researchers like Regina Stevens in episode one, that there is now resistance to tourism in the South Pacific. But the question is, will governments put words into action? And this is where policy and planning comes in. Governments are responsible for policy and planning when it comes to tourism, because if tourism isn't growing in a planned way, the question is whether local people will benefit from it, whether the environment will be protected as it should, and whether the social and cultural effects of tourism understood fully.

So that's the background to the tourism destination. I mean, as you can see out there, there's the sea, but at the moment it's cloudy and overcast. Usually to this morning it was bright and sunny.

There were birds. It was fish starfish in the water. So it doesn't look as good on screen as it does in real life. So when it comes to the lecture about building back better, it seems to me that policy and planning is vital to building back better. And there are some key concepts that we need to understand in the study of tourism.

Perhaps you've already discussed many of them. So forgive me if I repeat them, but I will just go through this list very briefly. When we talk about sustainable tourism or sustainable development.

It comes from the Brundtland Report, The Brundtland Report of 1987. If you don't know what it is, you can find it online. Stated that sustainable development was all about ensuring that the next generation inherits a planet that is in good or better condition than what we are handing over to them. Also, there's the question of winter as it was developed. There is likely to be change and we have to ask ourselves, So what are the limits to acceptable change and how do we measure those limits to acceptable change? And who decides what the allowable change should be? And there's the concept of carrying capacity.

We often have to ask ourselves, to what extent can a tourist destination or a place cope with tourism is 5000 tourism? The extreme carrying capacity. Is it 10,000? Is it 15,000? So for us as tourism researchers and for the industry, it's tourism practitioners. They're constantly trying to understand what is the capacity of this place, because at some point a destination will reach its reach, its capacity, which is why we see the concept of Overtourism coming up, right where people, local people are feeling that they are bearing the costs of growth, but they are not benefiting from the growth in tourism. And this this idea of sense of place, you know, as it as a destination becomes more developed, it starts to change, it starts to become less authentic.

And this is what we mean by a sense of place. Tourists go to a place to feel that they are in a unique place, right? Because if I go to Kyoto and I could be anywhere else in Japan, why do I go to Kyoto? So this idea of sense of place is particularly important when it comes to evaluating sustainable tourism and tourism development. The next concept, placemaking. When we talk about placemaking, we are talking about the processes where a place and its people become subject to tourism. The question is raised Who is responsible for placemaking and to what extent do local people decide how their place is represented and the type of development that takes place? Or is that the tourism industry that takes over everything? Then we talk about tourism impacts social, cultural, environmental and economic are the key impacts we talk about. And sometimes with tourism develops, we are talking about the trade off of impacts.

We might talk about increasing economic impacts, but perhaps having an impact on the environmental impacts of tourism. So to what extent do we trade off the environment for the economic trade offs that we receive in turn from tourism growth? Then the last point there is the newest, I suppose, discussion when it comes to tourism, this idea of regenerative regenerative tourism. To what extent can we visit a place and leave it better off than when we first got there? It reminds me of the old phrase We visit a place, take nothing but photographs, and leave nothing but footprints.

So to what extent can tourism leave a place better off? So my first part of this, this lecture is the policy and planning and the responses to paradigm shifts in tourism, because everybody expects the paradigm shift to take place in tourism. Yet yet what we see is that tourism is in some ways returning to its old models that many described as being unsustainable. So with that, I will take a backward glance and look at Cogat and then work forward to see how destinations are implementing new policies and new types of planning to ensure that the industry, when it recovers, recovers in a manner that allows it to be sustainable and regenerative. If that's the case, in 2020, at the height of the pandemic, we asked ourselves, you know, what will be the key to tourism recovery? At that point, we thought that making vaccines available to everybody will be the key to a fast tourism recovery. Vaccine passports. There was also the issue of vaccine equity.

Which countries had the vaccine? Poor countries didn't. How are we able to deal with a tourism situation where only people in the rich countries had a high uptake of the vaccine while in poor countries people didn't? And how do we reconcile trouble that people will make from rich countries to developing countries, or indeed in countries that are the same as themselves? But of course, this conversation, which is two years old, is now not as relevant as it was back then. So we found that attempts to reboot international travel on a wider scale have failed due to the successive ways of COVID 19, and it's only starting to come back now.

More than a year after most borders were open. With borders closed, many countries put a focus on attracting domestic tourists instead. And while this helps maintain economic stability in countries such as China and Japan, because their citizens weren't going overseas to spend money, right, They were spending money in the country. So it kept the money in China and Japan.

But to what extent is this going to continue to happen as borders and a vaccine requirements change and hopes for the swift recovery of international tourism were pinned on the distribution of the vaccine, which we now know is something that has mostly been successful in being distributed to countries around the world. We posed three questions that are important for tourism policy and planning. What travel regulations will prove effective? How will airlines restart their businesses? And will traveler confidence return? With first question, we see the travel. Travel regulations are ongoing.

They are constantly changing to fit in with the changing circumstances. But what we know is that most destinations were not prepared for the pandemic. How can airlines restart their businesses? This is one of the major issues for tourism recovery.

Many airlines are not back to full capacity yet, and airfares are very expensive, which is discouraging the return of international travel. And the third question will traveler confidence return, especially in Japan? It was quite obvious that Japanese weren't prepared to go overseas because of the risks involved, the health risks involved. When will people return? The confidence that they had? And we see that there was chaos and we see now that in the summer, northern hemisphere summer, the same kind of chaos is expected as there was last year.

Travel regulations driven by policy have been largely trial and error. In other words, educated guess where under preparedness was common and made worse by an inability to harness a common collaborative approach worldwide. Countries weren't working with each other. They were working on their own to procure vaccines for their own people, but not for others, and not realizing that in a global world we are all together on this. Vaccine equity, vaccine passports and nondiscriminatory requirements were especially prominent, especially anti-Asian sentiment that emerged in many Western destinations. And then now we talk.

We hear of the pandemic leading to a global recession. Economic recession. How might that impact travelers in the travel industry? And this is why we need effective government policies to support the tourism industry during the pandemic.

Governments provided cash subsidies to the tourism industry, cash support to pay for employees wages and vouchers to stimulate domestic tourism. For example, in Japan, the go to travel campaign was quite common. And as we see, airlines are still struggling to bring back capacity.

Given the time lag in between making the decision to start flying again and the preparation of aircraft and crew. As a result, airfares are still very, very high. For example, traveling to Australia and from Sydney to to Kansai used to be about $700, but now you can't get it fair for less than $2,000. And then we see countries like Japan open cautiously. Japan only open on the 11th of October less than six months ago, and they were worried about bad mannered foreigners who weren't sticking to health protocols, simple things like wearing a mask, sanitizing. And of course, we see key markets in Asia trying to convince their citizens that travels abroad should region.

We see governments are searching for pathways that lead to rapid economic recovery and increased social engagement while striving to maintain public health and pandemic protocols. And governments mostly now have border entry requirements that have been removed. They recognize the urgency to reassure citizens that pandemic management was being exercised and that travelers weren't going to be carriers of coronavirus contagion again. But this raises a lot of questions. Will we ever be prepared for the next pandemic? We also found countries like Japan policies that building confidence in destination communities and the tourism supply chain were important policies on economic assistance to businesses to provide weight, replacement for wages, and for and for travelers policies around the requirements to meet pandemic protocols, whether they be tests, certification or something else. The more barriers we have in place for travel, the more unlikely people will travel.

And this question is one that we should ask ourselves as a tourism industry. Are we going to be ready for the next COVID wave or the next pandemic, whatever it might be? Because we now know that a global pandemic has major implications for the global tourism industry. So when people say there has been a paradigm shift, we have to ask ourselves, as they really be in a paradigm shift, or are we seeing a return to tourism patterns from before COVID? Early indications now over the Northern Hemisphere summer demonstrates that tourists have returned and are returning in force. We see that flights between North America and Europe are almost back to 100% of what it was in 2019.

But demand, for instance, for international travel has still been impacted by multiple factors. The effects of the Russia-Ukraine war continue to underline security fears. Cost of international travel remains comparatively high, and this is associated energy costs and supply chain constraints. And we also see the fears of a potential economic US led global recession.

What would happen if a global recession started in the US and continued elsewhere? That would surely have an impact on tourism. So for us as a tourism industry, it's very difficult to plan and make policies because there are many unknown variables that will that are likely to emerge. And we ask ourselves now when will COVID stop being a global emergency? Many people say that COVID hasn't really gone away.

We have seen the highest number of infections in many countries across the world. And the World Health Organization says they cannot say that the public health emergency is over when millions of cases and thousands of deaths are still occurring on a daily basis. What does this mean for international travel? What signal is it sending to researchers, to manufacturers and to investigators developing new drugs and new vaccines? Is we going to experience something bigger and worse? And a second point, can we say that tourism has returned been the largest market for international travel? China still remain subdued, although in Japan, the reports are that they are starting to come back slowly. But most forecasts are that tourism in the Asia-Pacific will not recover until 2024, until China's borders open in 2019. Before the COVID 19 outbreak, 154.6 million Chinese traveled outside the country and there's a plane going overhead.

So excuse me for that noise. This is what happens when you do a live presentation from a tourism destination and this idea of encouraging travelers to travel again, how do we convince them that travel is safe? To what extent can you say that the spread of coronavirus is largely under control? We see, for example, the World Travel and Tourism Council and their campaign Safe travels, introducing global protocols and in a stand book, some destination border entry requirements still too onerous. We have to ask ourselves this question.

Although overall, apart from China, most countries have relaxed their border control requirements. What reaction would another pandemic likely cause? The tourism industry. And as a result, we see that caution against international travel remains high for travelers. To what extent will confidence return is something that the tourism industry is asking themselves? The last time we had a paradigm shift in tourism, we saw it was during September 11, 2000, when planes were flown directly into buildings in New York.

Right. That had a major impact on the way we travel. It meant security procedures would change quite considerably. There was a time when we didn't have to take off our shoes and coats and we could take water bottles on the plane. We didn't have to open our bags and show our computer. That was the last paradigm shift because it changed tourism considerably.

And there were many calls that said this will be the end of tourism. But of course, that never happened. Tourism has a habit of bouncing back, so travel patterns have changed as a result of the pandemic. But have they changed for good in particular? Transport systems. And we argue that for once, the governments around the world, once in a lifetime, have a chance to proactively shape how transport is delivered and used and to support and promote the most effective transport modes. And of course, we see things like flight chain where people are saying, no more flying.

If you're going to go somewhere, get a train instead. But of course, it's difficult for island countries like this where the only way to get to the Pacific islands is to fly where you can come on a on a ship as well. But that will take a long time. So how do we break down the habits and attitudes that underpin so many decisions at all levels as to how, where, when and why we travel? We see that the tourism agency in Japan, the Japanese National Tourist office, is saying that travel will reach pre-pandemic levels by 2025 and their responses have focused on some of the following Adjusting border entry requirements, implementing public health support for tourism, destination marketing to ensure to assure potential travelers that they are safe and to encourage visitation. Investing in domestic tourism recovery through direct industry subsidy will come incentivizing international tourists to return the three air fares and travel vouchers and incentivizing domestic tourists to travel around the country by deals and discounts such as the Go to travel campaign in Japan.

We see that for the Japanese government to achieve the international arrivals of 2019 before PAN, before the pandemic in 2025, they must address the following They must restore traveler confidence. Right? Because without traveler confidence, people will be reluctant to travel. They must support tourism businesses to adapt and survive. They must promote domestic tourism and support.

Seyfried Side of international tourism, rather than rushing domestic tourism for economic recovery, but not having the health policies in place, providing clear information to travelers and businesses and limiting uncertainty, evolving response measures to maintain capacity in the sector and address gaps in supports. So for example, during the pandemic, many employees of the tourism industry. So as the recovery takes place, many businesses are finding themselves short of employees and employees and not coming back to tourism because they have found jobs in other industries that are paying them better. How do we strengthen cooperation within and between countries to help manage the recovery of tourism, but also deal with the crisis that comes up? And of course, building more resilient and sustainable tourism in countries is the main goal right? And many of the points above talk about how we might be able to do that as the UNWTO or the United Nations World Tourism Organization stated. International tourism is on track to reach 65% to prevent pandemic levels by the end of 2022, which they came close and an estimated 700 million tourists traveling between January and September in 2021, equating to 63% of 2019 levels. So by the end of 2021, recovery was well on the way.

And as you will hear, tourism industry from different countries saying that there is a demand for travel and that with the improved confidence levels and the limiting of restrictions, this is likely to help the global tourism industry achieved a bounce back in 2023. We saw that when Japan opened its borders on the 11th of October, tourists returned quite rapidly. This resulted in good economic growth. And as Julie Simpson from the World Travel and Tourism Council said over the past two years, this is 2021 and 2022, the global travel and tourism sector had suffered tremendous losses when it last year, 2022, was poised for a strong recovery.

And we did see a strong recovery in many destinations. The world travel and tourism Council also said that the sector could recover more than 58 million jobs or 8.6 trillion. And this is why we want tourism to come back, because it provides so much employment for so many.

And as people start traveling again, governments must implement simplified rules, including the use of digital solutions. For example, here in Vanuatu, I still have to provide my pandemic certification to show that I've been vaccinated at least three times. Travelers without it will find it difficult getting into the destination. But how can we how can we move away from that and digitalize everything so that travelers don't have to carry lots of documents with them? They can just have their information verified when they arrive in a destination. And contactless travel guarantees safety in the Asia-Pacific.

This is what Pacific Asia Travel Association has as forecast. They said that international recovery to and within the Asia-Pacific is projected to return towards the end of 2024. So far, we see this recovery taking place as China slowly opens. We see tourists coming back. We see Thailand receiving many, many tourists and already getting close to the 2019 figures, as Japan is still cautious with its tourism industry, the following policy conditions influencing recoveries have been shaped by several key factors.

For example, the Japanese yen is at historical lows, 24 year lows, in fact, making Japan a very attractive destination and a cost effective one or entry ticket to international tourists have opened in the last six months and already we see really strong growth. Some in Japan said perhaps the Japanese government should have opened the borders earlier. Some COVID mitigation measures remain, especially for infected travelers to be to be quarantined and for unvaccinated travelers still to provide proof of a negative COVID test and a focus on achieving medium to long term growth targets are still being reinforced. For example, before the Tokyo Olympics of 2020, which happened in 2021. Japan was expecting a growth of tourists 30 million at the end of 2020 and then to 60 million at the end of 2030. The pandemic adjusted those figures, but now we hear the Japanese government saying that by 2030 they expect 60 million tourists.

In other words, a doubling over a period of seven years. And we see tourism as tourism starts to recover. There are labor force issues there, not enough people to to work in tourism. That is part of the the recovery that needs to take place in a country like Australia where I'm based. Tourism in Australia is seeing a very slow recovery because we see that travelers are not traveling long distances so much anymore. They are traveling short and medium haul distances in Australia.

Border entry requirements have been so simplified, high airfares remain a constraint. Inbound Travel Australia is at the end of the world. Right? So how do we continue to to improve our tourism industry if airfares remain high as well as airfares remaining high, their capacity is constrained.

So Australia is a relatively high priced destination, high cost of tourism services, and Chinese outbound travel is the key to tourism recovery. But yet that is yet to happen. Domestic transport options are limited and there are tourism labor force constraints as well. So it's a good time to get a position in the tourism industry.

We see that the return of tourism to Japan has seen this enormous economic growth once again. But I think I've covered most of this already, so I will skip past this slide. So while the pandemic may have grounded the world, it has also been a catalyst for change as the tourism industry considers the future of travel.

In your experience, proposed by travel, brands reflect the profound societal changes that are complex our relationship with the environment. People have said that the pandemic has made us more conscious about our social and environmental relationships. How we travel is not just about how we spend our leisure time, but increasingly it should reflect the values of an entire society. So my second and final part is about what all of this means for policy and planning, and especially for overtourism that has occurred over the years.

So this is one example. And in a city in Sydney that talks about how without tourism, advertising or without tourism development plans, tourists find their way to popular destinations. The question is this is a place called Segal Rocks in Sydney, where councils are telling tourists to stay away from the town because it would be too many tourists.

How can we plan for these things? In some ways this is like the situation in Kyoto before the pandemic, where tourist pollution was a problem, right? Or Kunkel could go where tourists were seen as polluting the natural environment of Kyoto and whether we had reached the limits of which the city and its people could deal with tourism. In articles we wrote about Overtourism as a glowing, growing global problem in the Spanish city of Barcelona, where that photo was taken. Tourism was seen as an occupation for people taking over a destination. Then we see in this book that we wrote how tourists were asking for their spaces, for separate spaces to be provided for tourists, and how some places within a local community should be seen as out of out of bounds for tourists. You know, tourist zones.

But tourists are allowed to go where they don't live locally. But of course, companies like Airbnb said, you know, if you come and stay at an Airbnb. You will live like a local. But did anybody ask the locals what this means? We see the same problem happening in in kilter where in some parts of Kyoto people were.

There was an explosion of mini tackle or short stay places. How does that have an impact on the local people if they have no control over that? Now it's getting dark and I'm just looking behind me so that we have enough light. And then this this question of overtourism occurs because of poor policy and planning. So I would encourage you to watch this. This

documentary, which is available on YouTube. It gives you a good indication and a good example of why policy and planning is important to avoid the impacts of overtourism on sustainable tourism. This is a new documentary that just came out recently as well. The Last Tourist making the statement that travel has lost its way. In other words, at a time when travel was about development and people to people relations, travel has become an indulgence now. It's become about consumption with tourists don't care so much about the impact, where governments don't care so much about the local people, but more about the economic impact that they making.

So when we talk about tourism and the troubles with tourism, very often, this is one of the key issues that comes up. To what extent has policy and planning ensured that the right type of tourism and the right level of tourism is taking place in a destination? This film in in in Laos, in Southeast Asia, how tourists to a village changed the lifestyle so considerably. And this is what we need to understand.

Tourism changes things, but to what extent and the to to to what extent? And that what is the type of change that communities will accept. Now, sometimes change happens quickly. Sometimes change happens slower. We see, for example, in Bali now Bali's coming.

It has brought in many, many new laws to ensure that tourists behave themselves. But of course, what this means is tourists are saying, I do not want to go to a destination where where there are too many rules upon me. Now, while I'm here, what I am researching with my colleague, Dr. Anne Hardy from the University of Tasmania.

So this is the party. So what I think we should do is we can have a discussion about tourism and I will ask and saying, what do you think are the barriers to sustainable tourism development? Well, in which region of the world anyway, in destinations generally, let's say Australia or Japan. You've been to Japan and was in Japan last year. Okay. I think probably one of the biggest barriers is finances, because I think at the moment a lot of the tourism industry is recovering from the effects of the COVID pandemic, particularly in smaller destinations. And so I think finance is probably the biggest one, but the first one is probably knowledge. Yes. So knowledge first and then probably finance is probably the second.

So in a country like Vanuatu, I just described it then where we are. What do you think is the biggest barrier to tourism development here? Oh, absolutely. Well, knowledge in finance, totally, because I think this country has been hit. When you say knowledge, you mean skills and. Well, actually knowledge of what it is in the first place that, you know, it involves, you know, protecting the communities, protects the environment, financial sustainability in terms of keeping the money in the in the in the location and also visitor satisfaction.

So I think we often also forget about business dissatisfaction. And I think I don't think of sustainable tourism as a trinity. I think it is or okay. And of course, and was in Japan last year, we and all the students watching are in Hokkaido.

Right. And it's from Tasmania, which is at the bottom of Australia. Mm hmm.

So in terms of sustainable tourism in Japan or the tourism product in Japan, can you can you explain what you feel as a foreigner, how you feel about the Japanese tourism product? Okay. I feel like it's really undersold, actually, because I think the amazing thing about Japan as a destination, unlike many destinations around the world, is that it has a as a traveler, when you go there, you get a really strong sense of, you know, you can have Japanese food. It's easy to buy Japanese labeled products.

It's easy to, you know, engage with Japanese owned products that sort of businesses. And so actually a lot of what it already does is possibly sustainable tourism in that it's know locally owned money goes back into the country. So we think about that.

A lot of it's already been done, but it's not necessarily been sold as such. So what to you stood out about your experience in Japan? For me, it was the culture. It was actually the cultural experience. Well, it was actually a complete blend of the cultural natural experiences.

So the ability to go over to a place where there's, you know, you can barely many of the towns where we went, there wasn't a lot of English. And for me, that was actually great because for me that it shows that this this is a destination that's actually managed to, you know, keep it be resilient in terms of maintaining its culture and its language. So that stood out for me, the cultural aspects, the food, the the dress and but also the natural environment was amazing. Really amazing. Okay. Yeah. Thank you. I got to.

And since you can stay there, so this is a last comment, the last one of the last documentaries that I think you should watch. It also talks about how as tourism develops over time, the kinds of decisions that undermine the sustainability of the place. So gringo trails gringo is a is a Spanish word for a foreigner or a white man that comes to Latin America. And how the growth in tourism has impacted both positive and negative. The community there nearly finished then. Okay, so that's my concluding slide, of course, because this is a recorded session.

I will join you after this for question and answer perhaps Dr. Mohsen, we call him, I will coordinate a announced question and answer session. And the reason we recorded this is this is a problem. We know how important Wi-Fi is for travelers. I mean, everybody wants to share their photos, but in a country, especially in less developed countries, but Wi-Fi is problematic.

So hopefully I can join you for Q&A. You know, as travelers, we are so used to being able to get on our phone and communicate with the rest of the world. But imagine being in a place where there's no Wi-Fi or Wi-Fi drops out. So in this large resort, I'm at one end and ends at the other end to get the best Wi-Fi. We have to come and sit here in the restaurant to be able to do this.

It's a constraint to tourism developed because we know that to a satisfaction is important. The more small things that take away from the overall satisfaction, the less happy they become. And we know the tourism and destination development also heavily relies on word of mouth. But so with that said, thank you very much for listening and we'll look forward to joining me for Q&A. If we can say thank you to Dr.

and Hadi from the University of Tasmania and is a very famous professor and his ANZ's work is about tracking tourists. So if ever you you need to come up with an essay about tourism technology and you want to find out about how we can understand tourists movement around a destination, look for an Hadi in Google Scholar or in any any, any of the places you do your research, you will find that information. So with that said, thank you very much, everybody, for listening. Now let's hope we can join you for Q&A at any minute. Okay. Thank you. And it's the very things professor and his guest about tracking tourists safe.

Anywhere you need to come up with that, an essay about tourism technology. And you want to find out about how we can take tourists movement around a destination. Look for anybody in Google Scholar or any any of the places you do hello Joseph information. So with that, I'm going to go to a chair here. We can join you for Q&A.

Sorry, I have some tech issues to ask you are finished playing the widow out now. It's fine. So we received to Q&A, but before that, welcome back and congratulations. You made it. You find out why. Wife Eventually.

And I have a lot I want you to comment. Yes, I can hear you loud and clear. And it's really amazed to follow your research. For more than five years before I. I heard your presentation about Pacific Island and later about Japan. Now is about a post pandemic.

Before I have a toss of a question, I will give the floor to our student. And there is also a technology antennas at 8:00. So we have more or less around 40 minutes for Khun a a singer. That's quite enough. Okay. Okay.

So maybe let me read the first question from Liu. You're hoping he said she says, Hi, Professor Joseph, thank you so much for your informative presentation. This is Liu. You're a doctor, first year student at Hokkaido University. I have a question regarding the virtual tourism in the post-pandemic era. So during the worldwide lockdown in 2020, worries forms of water tourism have shown their importance.

For example, watching livestream travel on TikTok was once very popular in China in the post pandemic, as well as in the more remote future. So what extent do you think water tourism will contribute to the paradigm shift in the tourism industry? Yes. Well, thank you very much for the invitation and thank you to everyone who's here also. Hi to Johan. Professor Johan, if you there as before that, I would like to apologize for the quality of the Wi-Fi.

Right. I was supposed to do this class in Australia, but unfortunately, my travel plans to Japan changed. I'm here for the Asian Development Bank and we are looking at tourism development behind me. You will see the beautiful tropical environment and the sea is not too far away. I wish you could all be here.

It's very warm, but it's warm in in in Hokkaido as well. I believe so by virtual tourism and the pandemic shift. I think what is what is what is evident is that virtual tourism, obviously had perfect a perfect set of circumstances. People couldn't travel. There was a shift to the online environment, so virtual travel gained popularity at that point.

But the question I think ping you you raise it is possibly one and maybe I can try and paraphrase or guess that perhaps you're asking, is virtual tourism something that's going to continue to strengthen over time? And if I may, I may compare that to something here that this is one of the reasons we're here. During the pandemic, domestic tourism around the world is quite complete. Japan was one example, and that's because people weren't able to travel overseas. Right. Is that going to be a permanent situation or will people now continue to travel overseas because they have the potential to do that and the and the ability? Now, I think it's the same with virtual tourism. I'm not the school where I think tourism is a people to people experience face to face rather than virtual and online.

I think there's a place for virtual tourism in terms of when you study marketing, tourists finding themselves in the dreaming phase, right, when they're looking at going somewhere. I think virtual tourism and be good at the dreaming phase. It can also be good at providing information and demonstrating people's experiences as a way of enticing people to go to the destination. Is it going to replace face to face travel? Very unlikely. I would say. For example, if we look at the data between travel, between North America and Britain, that's already reached about 95% of the pre-COVID capacity.

We see countries like Thailand. pre-COVID capacities, even because even in Japan, I think inbound tourism arrivals have increased a lot quicker than they anticipated and especially will do this when when Chinese travelers regain the confidence to travel again. So if I was if I was a man, a betting man, you know, betting money on where the virtual tourism will continue to to to to flourish or not, I would probably say it will continue to be a part of driving tourism demand, but I doubt that it will ever replace the desire to for face to face encounters that we tourists have. Okay. Thank you very much.

We have three more questions piling up, so let's do it one by one. So another question from Dali Harnick. I'm sorry if I pronounce your name right. It says Excellent webinar regarding financing. Why have governments evidently been slow to request World Bank IMF funds? Yes, very good question, Dale. And I think Dale is a a LinkedIn friend who I've never met in person.

But thank you, Dave, for your question. Thank you for coming to this webinar. It's a very important question, especially here where I am in in Vanuatu, small island developing state where the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, Jica, the Japanese development agency COCA, the Korean Development Agency, U.S. aid, the British Development Agency, DFID, they've all seen tourism as a vehicle for development. Why have been why have they been slow, as Dale asks? Well, there's a very good reason. Very often organizations, let's call them bilateral, organized multilateral organizations like the World Bank and the IMF or the Asian Development Bank, they often are keen to to provide financing that is evidence based.

Now, all while while evidence of the long term impacts of COVID very difficult to understand, they remain very shy in terms of engaging in investing in tourism. I mean, here Dr. NRD and I are on this assignment for the Asian Development Bank.

There is a desire to invest more in tourism in the industry, but our job here is to try and build on the evidence. That's that's that's very thin on the ground. So when we talk about development agencies, when we talk about investors, when we talk about someone who may be wanting to develop a resort, evidence drives good decision making.

Evidence drives policy and planning. And in the absence of evidence, making decisions becomes a bit tricky. So that's the reason, Dale, that I can see from my perspective. You've. Okay. Thank you much.

Okay. Next one is Talk Korea or Kochi. So I think the number of tourists will continue to fluctuate due to a sudden disaster or pandemic in the future, especially when there are few tourists. How should we keep the employment on tourism and keep the quality as tourist destinations? How do you evaluate the idea of collaboration with other industry, for instance, work costs and business plus tourism, resort therapy, health care plus tourism and others to question? Thank you for your question.

There are several parts to it, and I will try and answer that quickly within the time constraints. So you are right. We are in a in a situation of more uncertainty than normal right now. You know, the question remains, are we past the pandemic or is the pandemic still with us? Now, you will have varying discussions around this. So, you know, we found that when the pandemic occurred globally, we were we were very much underprepared to deal with this. We had never anticipated something of this magnitude.

What if we have another one? That's that's unintended and unforeseen. Will we be able to deal with it now? We hope that the pandemic has given us an ability to be forward looking, to be able to create scenarios where there are particular crises and we are able to deal with them. But of course, as crises tend to be, we don't really know what the full extent will be. So I agree we operate in a in a climate of great uncertainty.

And then beyond the pandemic, there are issues about climate change. So we always your next question is, especially when there are few or should we keep the employment on tourism and tourist destinations? Now, that is a very interesting question because in a destination like this, as recovery takes place, it's quite evident that people, employees in the tourism industry have left the tourism industry to go and work elsewhere. They've discovered high paying jobs in other industries in Vanuatu as an example. Many have gone to Australia and New Zealand to work in the farming industry, where they will get paid far more. So it's a really important question Should we continue promoting tourism when it when, when it's still recovering? I think we should, because soon enough we see the recovery will take place, I would think, quite rapidly.

And are we going to be prepared to have the workforce on the ground? Because if you don't have the workforce to deliver tourism experiences, then that has an impact on satisfaction. That has an impact on capacity. We see, for example, when when borders started opening over 18 months, two years ago, airlines were facing this very problem. Staff had gone to other industries and then being able to restart and retrain staff is a very difficult situation. So it's a balancing act.

How much do we invest in our employees in maintaining and keeping them? How much do we do? We saved on employment costs, on the other hand, until tourism recovers. Now, many tourism organizations and many destinations, we see that the industry has just done that. They've let employees go. But suddenly, as the demand has as kicked up, as it has increased, they found themselves running behind because they did not have the employees.

So this is a very tricky question for the tourism industry. For us as university professors, we have to ask ourselves what kind of employment futures will tourism students have? And, you know, has the tourism industry learned from this and will they reward tourism employees far better than they had been in the past? And this is really in an in a developing country like this one, tourism provides real alternatives for employment because there are not and there are very few other other opportunities. But even even in that situation, there is a labor force crisis.

And I think if anything's going to going to prevent the crisis, but to prevent the tourism industry from recovering quickly, it's the labor force crisis. Now, if I can go to your last question, you talk about vacation resorts, therapy, health care, tourism and others. Now, certainly workstation or digital nomads increase quite rapidly because of the pandemic. Wellness, tourism and health care tourism did so as well. So while some sectors of the tourism industry had a downturn, other sectors became more relevant. Now we'll continue into the future.

This is a very difficult thing to kind of forecast in the very uncertain environment. But I would say when it comes to work in the digital nomads, the pandemic has taught us that there are other ways of working that we don't all have to go into an office, for example, here, not here, but in Australia, where I live, there are empty city office buildings because people aren't going into work. What's going to be happening with them in the near future? You know, some organizations are saying we want employees to come back to work. Productivity is down.

So I think there is still a little bit more to develop in the next couple of years before we can see that becoming a permanent thing. Thank you, Melissa. Okay. Well, it's another question from Dali, and we would like to know what could the best steps to accelerate the transition to sustainable or regenerative tourism? That's a good thank you. It's a very good question.

And the bigger question than many are asking is what is the difference between sustainable and regenerative tourism? Right. Is there a difference? Now, there's also the problem with regenerative tourism. It's become this populist thing that that you can now see in marketing. And to some degree, it gives you the feeling of greenwashing.

Right. But if we could first start with defining sustainable tourism and regenerative tourism. Sustainable tourism comes from the 1987 Brundtland report on sustainable development, where it was about intergenerational equity. In other words, is what we doing today going to compromise the planet for the next generation? Right. That's what sustainable development and its its its origins. Ask regenerative tourism has become very popularized in the in the last couple of years.

Now regenerative development is not new thing. Many indigenous communities have been practicing this. Many rural communities in Japan have been practicing this permaculture permaculture roots in agriculture have been practicing this, where the idea is what we do and the activities we undertake should improve rather than degrade the environment we're in. So for example, if I if I have a corn farm, the idea would be that what I'm doing improves the state of the land rather than degrading it, which is the common case for many industrial agricultural practices. Right where we use artificial but we use supplementary fertilizers to replenish the earth that we've had all of the the the good things taken out of. Now, regenerative tourism suggests that with tourism we can make the destination better.

For example, here we're saying that with regenerative tourism, the reef, which is about 100 meters away, will have the ability to regenerate itself. We're saying that the the the products that the crops that we get from the land leaves the land in a better state. We're saying that the fishing we do we are mindful that we are not overfishing so that to the end we are not catching fish that are too small so that we allow fisheries stock to replenish itself. Now, how do we accelerate this now? I think we see this already accelerating from an ideas point of view, from a research point of view, from a tourism policy and planning. But in my mind, the way we can accelerate regenerative tourism is changing tourist behavior. I think usually we start from the top and we say policy and planning is important and we work our way down.

I think tourist behavior is working from the bottom up because if we change tourist behavior and we change the demand for certain products, we then force the industry to to provide those products for us. Right. But, you know, do I have faith in consumers to want to make good decisions? I mean, it's very difficult to have faith in consumers generally because across the planet, you know, we are largely living consumerist lifestyles, consumptive lifestyles. We see problems with fast fashion as an example.

We see problems with sustainable agriculture. Right. So all the while, we see that despite the calls for a better way of living and existing with the planet through regenerative tourism as an example, do think without that bottom

2023-06-10 16:48