The correcting feature of typewriters is not what I thought

Y’know, sometimes, as I desperately look for a topic to cover… relatively quickly after realizing the one I’ve been working on needs to be delayed indefinitely thanks to a thing I just discovered and need to investigate further, I find myself pursuing the bowels of my storage area. My hope is that between bouts of getting mad at myself for letting it deteriorate into the state it’s become, I’ll find a thing which gets me out of this jam and hammering out a script. Fittingly, I glanced at my collection of typewriters sitting on the bottom shelf (are you really surprised I have a collection of typewriters?) and I realized I think it’s time for a Technology… Correction! See, I’m just old enough for typewriters to have been lingering on in my childhood.

Even as personal computers, mature word processing, and consumer printers made them seemingly irrelevant, they were still handy for certain things. Like, for instance, addressing an envelope. Do you really want to faff with Word 95, figure out how to get your crappy inkjet printer to accept an envelope, probably experience a multitude of paper jams because you didn’t realize it’s gotta go sideways, only to finally have what looks like success at last... until you see that the text is sideways because you didn’t do the page setup correctly, or… do you just stick the envelope in a typewriter and have at it? Lots of people would much rather just do it the old fashioned way, especially for one-offs.

Once you know your way around a typewriter, well you can see exactly where it’s about to slap a letter onto the envelope. It’s a much more manual process, sure, but also way more straightforward. Of course, eventually the whole “printing onto envelopes” business would get better, and also people just don’t really need to do that very often anymore. Plus, setting aside the decreasing need to mail stuff, uh handwriting is and was always an option.

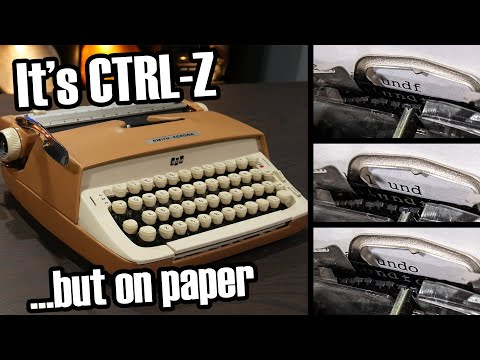

So the typewriter would eventually fade into obscurity. Although a few models are still being made, believe it or not. Anyway, before they all got tucked away into attics, typewriters gained a very forgiving feature. Take a look; make a mistake, and just like that - the mistake is gone. Now I’m sure that to some of you watching, the idea of a young whippersnapper such as myself being astonished by the correcting feature of a typewriter is laughable.

But see, it’s not that it can do it that I find interesting— it’s that I was completely wrong about how this works. You might think, as I did, that this is covering up the ink with a white substance, like correction fluid also known as white-out. And, ok, some typewriters did do that. But this one works with colored paper, so that’s obviously not what’s happening.

What it’s actually doing is undoing what it just did. See, typewriters went through a change around the middle of the last century which fundamentally altered how they put letters on the page. And it was that change that made this possible. Compare the text written by a typewriter before and after this change. On the left we have an old-fashioned typewriter, and on the right a newfangled one.

The newer typewriter has a much crisper and more uniform appearance to the text it produces. As a matter of fact this looks like it could have come from a modern laser printer. The other typewriter produced a much more… gritty text. It doesn’t have crisp edges, there’s a vague texture in the solid parts, and in general this looks… old-fashioned.

Nevermind the typeface, this looks like how I imagine a typewritten document to look whereas the other text looks like, well, a printout of a Word document done in courier. What changed between these two typewriters? The ribbon. OK, a great deal more than that changed but the difference in the ribbon is what’s responsible for the dramatically different text, and the ability to make it disappear. Before we get into that, though, I should probably give you a brief overview of a typewriter. [THUNK] Here we have a basic portable, manual typewriter. This is what I always thought of when I thought “typewriter,” which makes sense as this design was more or less the standard for half a century, with countless typewriters from many manufacturers all functioning more or less identically to this one.

Each one of the keys is connected to a metal arm called the typebar which has on its end a small metal casting with two reversed symbols protruding from its surface. Those symbols just so happen to match the ones on the keys. Collectively, these typebars are known as the basket. This weird thing with the hard rubber roller bit back here is called the carriage and it holds the paper on which you intend to typewrite. With paper in place, as a key is depressed the type bar leaves the basket and approaches the paper. As that happens, an ink-soaked ribbon is lifted upward so that it comes between the typebar and the paper.

With sufficient force, the protruding symbol on the typebar presses through the ribbon and contacts the paper. That will transfer some of the ribbon’s ink to the paper in the shape of the protruding symbol, and the end result is that symbol appears on the page. Pretty striking.

After that happens, the ribbon moves out of the way so you can see what you’ve just typed. The semi-soft surface of the rubber roller, which by the way is called the platen, helps the ink transfer happen more completely by allowing the typebar to press into the paper ever-so-slightly. You may have noticed, possibly because I told you, that every typebar has not one, but two symbols on it. For the letters of the alphabet, those are the lower- and uppercase version of each letter, and for the other keys… it’s whatever two glyphs the manufacturer decided belong on that key. Selecting between them is accomplished with these; The shift keys.

And pressing them shifts the location of the typebasket into the machine so that the top of each typebar is what will hit the ribbon and paper. This machine, like most, also features a shift lock which is simply a latch which holds down the typebasket. You release it by pressing either of the shift keys until it’s released. Because this thing is entirely manual and the typebasket is, y’know, metal and heavy… this is a pretty clunky experience. This is just not easy to use.

Here’s a Technology Connection for you; ever wonder why the keys on a keyboard are so weirdly staggered? If you’ve never noticed it before, nearly every keyboard out there doesn’t arrange the keys on a neat grid, and instead each successive row is shifted over, and even more weirdly, it’s a different amount from row to row. See, the row below the numbers is shifted over half the width of a key, with the second row’s keys centered below the gaps in the first row. That kinda makes sense but the third row is only shifted over by half as much from the second. That is a relic of the typewriter that lives on! Since in a typewriter the keys are arranged in four rows, and every key acts upon a single typebar in a linear arrangement, every row of keys has to be shifted over a bit to keep the linkages between key and typebar from landing on top of one another. Typewriter manufacturers could have designed the keys with different attachment points to the linkages to get around that but that almost never happened, and the staggered-key arrangement became standardized.

With so many people used to a keyboard with this staggering, it didn’t make sense to mix it up. And even once they had become simple buttons on computer keyboards the staggering was retained to give typists an easier transition. And we’re still doing it because the only thing better than perfect is standardized! In typewriters with a typebasket, the carriage (and thus the paper) moves as you type. That's probably why it’s called the carriage. This allows a much more compact design since the machine only needs to be large enough to contain the typebasket and keyboard.

And really it’s the only practical way to go about it since the keyboard and typebasket are part of the same bulky mechanism. So, a line of text is started with the carriage all the way... to the right, and each press of a key moves the carriage to the left one space in preparation for the next keystroke.

The space bar does the same thing but without actually typing anything, allowing you to leave a gap between characters because that’s how words work. Some typewriters, particularly those that write in languages that used accent or other diacritic marks, have some so-called dead keys which don’t move the carriage when you press them. That allows you to, say, type an accented e by first hitting the accent mark, which would slap it down but not move the carriage, and then hitting the e key.

That could have been accomplished with a backspace between two keystrokes, but when your language uses those marks a lot, dead keys are much more convenient. Anyway, as you keep on typing and approach the end of a line, the carriage will ring a little bell [adorable ding] to inform you that you have only about ten characters left before you hit the right hand margin, so either finish this word or get ready to hyphenate and start the next line. Starting the next line is accomplished by using this chrome bar, called the carriage return, which returns the carriage to the starting point. And that’s customizable - these little tabs back here can be moved, and they define the margins of the page. The left tab defines where the carriage stops when you return it— really handy for addressing envelopes! And the right tab triggers the little bell ten characters ahead of where it sits, warning you you’re near the end, and then stops the carriage at that point and keeps you from typing. This key, labeled M-R, is the margin release key which allows you to override the end stop in case the word you’re working on is just one or two characters too long and you’re willing to break the margin for it.

The margin-release key also allows you to go beyond the starting point if you hold it down while returning the carriage. Now, before this turns into a typewriter trivia tangent, which I suppose… too late. Uh, let’s just get back to the meat and potatoes of the ink and the ribbon. This typewriter, like many others, uses a simple ink-soaked cloth ribbon for making letters happen. That’s why the text it produces has that texture; you’re seeing the weave of the ribbon come through.

And since this is ordinary ink on ordinary paper, if you make a mistake you have few options. Special hard erasers for typewriters were available, and they would really just sand off the top surface of the paper and thus the ink from that spot. And of course once correction fluid hit the mainstream, there was that option, too.

But with a change in the typewriter’s ribbon, we would get not only crisper, darker text, but we’d get the ability to undo our mistakes without leaving a trace. This monster of a thing is an IBM Selectric III. That’s right, III. The Selectric series of typewriters is as iconic as it is fascinating.

Instead of a basket of typebars, these typewriters use an interchangeable typing element, known informally as the typeball and even more informally as the golf ball. The typeball sits inside of a moving type head. In this typewriter the paper is stationary and the typeball moves along the paper’s length as you type. The entire mechanism is powered by an electric motor, and pressing a key causes an amazingly quick and yet somehow still precise Rotate, Pitch, Wham maneuver, with the exact character you selected slamming into the ribbon and making a mark upon your paper.

It will forever be astounding to me that this machine manages to make all that happen in the blink of an eye, and with absolutely no perceptible variation between character landings. I mean, the text from the manual typewriter, which isn’t doing anything near as complex as this, is not consistent at all, but this whacky ball thing manages to rotate and tilt into place with such consistency that fancy script fonts like this one work perfectly! Did I mention you could get different fonts for this thing? And it can do either 10 or 12 characters per inch! Now this video isn’t about this typewriter. If you would like a better understanding of how this works, you should check out The Engineer Guy’s amazing and also way more concise than I could ever manage video on the subject. I’ll put links in all the places. What I want you to notice is the ribbon. The typewriter has one, of course, but it’s nothing like the fabric ribbon we’ve been looking at.

If I remove it... you can see (after I almost tore it) that it’s very very thin, and we can also see the letters that have been typed. Not great for sensitive locations; destroying these ribbon cartridges was often a matter of national security.

Anyway, these polymer ribbons are what make the text so crisp compared to the cloth ribbons of ye olden times. But, yeah, they’re also not what allows the correcting feature. IBM introduced carbon ribbons in 1949. Or maybe 1937.

Yeah it's not clear. Also I can’t even tell for sure if those are polymer ribbons. Anyway, it’s not important, polymer film ribbons allowed for complete transfer of their pigment material to the paper.

There’s undoubtedly some fascinating materials science that went into making the carbon stick to the paper which I am not even going to try to explain, but the end result was very dark, very crisp text on the page. The biggest disadvantage to this was that the ribbons were single-use, though being quite thin they lasted a long time. Oh also you can see everything that was written with that ribbon, which as I mentioned may not be desirable.

This particular ribbon, though, is different. It works just the same as any polymer ribbon, but some even more fascinating materials science was done to it to make the pigment not quite so sticky. This is a correctable film ribbon, which first made an appearance in the Correcting Selectric II in 1973.

It does a decently fine job sticking to paper, but its adhesion is just weak enough that with a bit of adhesive tape it can be lifted off. This white tape sitting near the ribbon is really just sticky tape, and when you press this key below the keyboard, the type head moves back one space and when you next press a key, it will lift the sticky tape into position instead of the ribbon. By smashing the same letter at the paper through the sticky tape, a very strong bond between the tape and the pigment is made. So, the pigment gets yanked right off the paper like nothing ever happened. At least… mostly. It usually takes a few hits to completely remove a letter.

Since this typewriter is purely mechanical, the correcting feature is fully manual. To undo a mistake, it’s best to hold down the correcting key and then hit the erroneous letter’s key a few times. Usually after the third strike, we have lift-off. The typewriter I showed you in the very beginning is a much newer, fully electronic typewriter. It uses a daisy wheel for its typing elements, a mechanically simpler arrangement than the IBM golf ball but which requires electronics to monitor its position as it spins and fire the striking solenoid at precisely the right time. Since it has those brains (and it uses them for other stuff, too, like spell-checking and line-by-line previewing if that’s your jam) it knows the last letter it punched out, and so simply hitting the correct button performs an automatic backspace and three whacks with the correcting tape.

In fact if you want you can have it correct an entire word. Now you might think that the ability to lift the words right off the page means the documents produced with these typewriters must have poor resiliency. But they’re actually quite durable.

If I use the back of a pen, I can’t rub these markings off. They’re really on there. Using an X-acto knife blade I can scratch them off, but it’s not any easier than scratching the toner off of a modern laser-printed document. The typewriter can take its words back so effectively because it’s not just the adhesion of the correction tape that does the job, it’s the fact that in the typewriter the same typing element that left the mark in the first place also applies the correction tape to the paper. That means it’s being pressed *hard* into the offending letter and, crucially, nowhere else on the paper.

Only the pigment is getting touched by the correction tape. Yes, if you put a piece of Scotch tape, use something to apply pressure, and lift it off you’ll end up with some of the text on the tape. But even then you don’t get it all and you’re likely to take some of the paper with you. I know I can get fascinated easily, but I think this is remarkable. I never imagined that a typewriter could play textual take backsies.

That just seemed well outside of the realm of possibility! I didn’t know that these letters aren't made with ink, so I thought the only possible cover-up was… a cover-up. Now, as I said earlier there were correcting typewriters that typed in ink and did put a white powder atop mistakes. As a matter of fact, the Correcting Selectric typewriter could be used with a standard inked ribbon, and a non-adhesive, white correction tape would simply hide your mistakes. But of course that only worked with white paper, and I can’t imagine that worked nearly as well as lifting the text off. Even if it did a fantastic job, you could always shine light through the paper and see that mistakes were made. Of course, if you were making carbon copies, well this wouldn’t work.

I mean, it would for the top one, but all the copies below would be royally… messed up. Then again by the time this feature hit the market, photocopiers were common in the office so carbon copies weren’t too much of a thing anymore. And actually photocopiers were a way to get around noticeable error correction using white-out. Yeah you could see the blob of white goo on the original, but copies will hide that swimmingly. Anyway, I think that’s it for now. It may not surprise you to learn that I wrote… quite a lot more about typewriters before trimming this down.

Like, for instance, how it’s actually kind of strange that this manual typewriter has a 1 and exclamation mark key. It was common practice for that key to just… not exist! And a lowercase L would be typed for the numeral one, and an exclamation mark was better known as "period backspace apostrophe." I was going into a really deep dive on this machine and others before realizing maybe I should cut to the chase. This was supposed to be quick after all. At least as quick as I can manage. But hey, if you all like this video, maybe I’ll revisit the topic later on.

It’s genuinely surprising just how many of our modern word processing conventions can be found right here in mechanical form. ♫ typographically smooth jazz ♫ …typewriters sitting on the bottom shelf. Are you really surprised… *sigh* Oh, that’s a live spider! I saw that this web was here… ooh. Or, doyou just stick it in the env… BBPPBP Don’t really need to do that much ah haaaa That’s obviously not what’s doing. This looks like this could’ve been come [flailing] In typewriters with a typebasket, the carriage and thus the… ahh! Oh.. Yeah, no thatshoulbe. Some typewriters... But its adhesion is just weak enough [hits typewriter with hand] that….

Well that didn’t work, did it? If you've never used a fully manual typewriter before, gosh is it not fun. The key travel is something like an entire inch - your fingers are powering the whacking, after all - so I cannot touch type with that thing at all. You didn't get to see an electric version of the same design - a motor does the whacking for you! If we cover this again I'll show you that fella. Much, MUCH easier to use.

'kay bye

2022-08-03 15:31