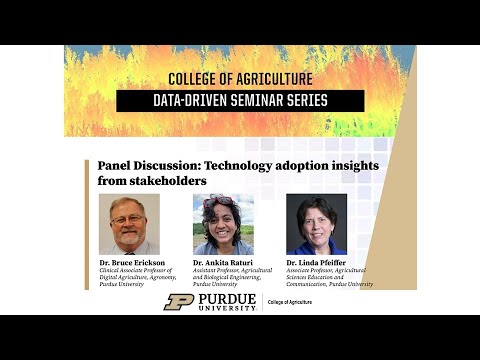

Panel Discussion: Technology adoption insights from stakeholders

Welcome to another episode of Digital Ag, Integrated Digital Forestry, and Plant Sciences Initiative seminar series. As you can see projected there, the three that are yet to come. So mark those on your calendar. The dates are already there on the calendar, but you just have to go with these events to hope to see you there.

The topic today is about technology adoption, getting insights from stakeholders about that. So I'm your moderator. I’m Dennis Buckmaster, Professor of ABE and Dean’s Fellow for Digital Ag.

So we have let's actually read them in order from my left to right, your right to left, Bruce Erickson who is a clinical associate professor in agronomy, does online education. Dr. Raturi, assistant professor in ABE and then Linda Pfeiffer, Associate Professor in Ag Sciences Education. So this is I have just a little bit of intro. I put up this one which came up on the screen capture not too long ago, reminding us that there is a tremendous amount of technology out there. It's not too different than there are a tremendous number of children.

There are a tremendous number of pets waiting to be adopted. There is a tremendous amount of technology to be adopted. And adoption really is the challenge. Not necessarily.

Even though this is what many of us do, it's not necessarily the development of the next tech. We need to do that, yes, but we need to get it adopted. So I wanted to just kick off the panel a little bit with the notion that it is solutions that get adopted, not technology. And so this is a slide actually taken from our Agtech innovation course. There is a nice website to talk to the 10 principles of innovation.

And I want to focus on the solutions, not technology. So an example is would you rather have a network of orbitals but that constantly send and receive geospatial data streams and synchronized blocks to triangulate your positions? Or would you rather have GPS or get lost in it? It's not the tech. It's the solution that gets adopted.

One Indiana company, Beck’s, one of their long standing mantras or I don't know their motto, but they sell us a stand of corn, not a bag of seed. It's a solution, not the tech and the one that I am personally involved with is this particle science separator for forages and GMR for dairy cattle. Like, people don't need a device to separate their forages and feed into size fractures. What they want is a rapid way to determine particle size so they can help reproductive health.

So keep in mind, during this discussion today, this difference of adopting technology versus adopting a solution, which happens to be technology, but make it more evident what is the problem that's been solved? Can I interject something? At this point, Dennis? No, you have to wait your turn. Wow, that's terrible when you’re good friends with the moderator. But you’re turn is next. Okay, so here's our plan. Brief presentations by Dr. Erickson, Dr.

Raturi and Dr. Pfeiffer, and then we'll have some good time for Q&A from you. I've got a couple of questions prepared, but I'm really anxious to hear the questions of those of you that are in attendance. So I hope you can gain some things today that might influence how you go about doing the research or the thing with the business that you’re in. So with that, Bruce, I'm going to hand you, effectively, the microphone.

Okay, it's my turn now, control. Okay. And the down button takes you forward. Okay. Without further ado. Okay, so something that you said that struck something inside of me and I just wanted to comment on that. Okay. We are selling solutions.

Or people are adopting solutions. But I think in many cases, companies continue to sell technologies too. And I guess I see that it's oftentimes the little shiny things that you need to adopt. And then in like household things, I think we're often you see that on consumer products. It’s the interesting new thing. So let me just go ahead and start if you've seen if you filled out the quiz, let me just go ahead and I have my main points couched around these four quiz questions.

Okay. So let's take a look at the first one here and oh other way. Okay, it's down. Okay. So you've had a chance to take a look at the question number one and the precision farming technology used on most of the acres in the United States, according to some of my survey work and according to the Economic Research Service. And what did you have for the answer to question number one? Who wants to? Okay, Christian, you've got to correct it was B, and that is the correct answer.

Okay. But probably with any technology adoption or solution adoption, it needs to be. Why is there so much autosteer guidance when we've had satellite imagery much longer, we've had it since like the 1960s and we've had variable rate fertilization for like at least 25, maybe 30 years. Okay. And so this is a panel discussion.

It's meant to be open. And so who would offer like to offer a solution? Why guidance has been so much more rapidly adopted as compared to imagery or as compared to V.R.T. and I just separate out variable rate fertilization.

Any thoughts on that? Yes, I guess. The satellite. Imagery was not my. Concern because of the spatial right and both and like the things. That's a very good point, although I would counter some to that if you include drone imagery or UAV imagery also in that it has not been very rapidly adopted either. Also, although the small spatial resolution has just been available here like the last few years.

Okay, so any other thoughts? Christian Yeah. The reason I guess, I guess is right was because it reminded me of a faculty tour that I took when I came here. I think maybe you were on that in 2005. And they're taken to to a farm. And it was in kind of a old corn grower. You might now.

And he was all excited because he had strap GPS device onto this tractor and he was able to go down the road straight. Now and plant the seeds and well, the path was wiggly and and so he was really excited that. You could put those. Lines down. For his corn and this was really an improvement for the work that he had always done. And so I.

See that the adoption was very easy, even more. So. I think the key point is they could see what the adoption is doing for them. That's what I would add. So again, this is a discussion type of thing.

And so but but variable rate fertilization, you can see that this part of the field is lighter soil. You can see that maybe the corn is taller and greener here. Why wouldn't it make sense to put on different amounts of fertilizer and why wouldn't that really pay? And why wouldn't like every farmer be doing that? Okay, they probably should be. But I think the key point I'm trying to make here is that auto guidance is something that you can adopt.

You can put it on your sprayer, your tractor or your combine. And for the most part, you can see immediate results from that and you can quantify those immediate results with imagery, whether it's satellite or airplane or drone. Okay. So you're getting this map of your field and you can see that things are different as compared to over here. But one of the key things that I think has been a constraint is we don't always know what to do based on that. It's different.

And the same thing with the yield map, too. I mean, we have made some advances and those lines keep going up, but we're still not quite where we thought we would be like 25 years ago when we started doing a lot of this stuff. And anyone, please feel free to disagree because that's where we learn and that's where this becomes fun, that there's dialog and interaction. And if Dennis and I get the big argument, I mean, someone will have to stop it. It's

okay. That was good. And I think the same thing with variable rate fertilization.

Again, we keep inching up. I think variable rate according to the USDA is just sort of 50% of the acres of fertilization in the United States. Based on the last survey that I showed in the information that we do is fairly similar to but it's them. I guess I'll just say that, you know, you can you can take a look at a crop field and it doesn't look complicated that you're driving by at 60 mile an hour and oh, there's a cornfield, there's a big field. But those growing environments are have turned out to be much more complicated than we ever thought.

I'm taking too much time to keep going. Okay. You’ve got three more. Okay. The biggest use of on farm crop data or decisions.

The biggest use of it is for decisions about fertilizers, seeds or pesticide rights. Where is data currently being used the most? Who wants to venture something on that out of? I would say purely, I guess. I honestly don't know the answer. My guess would be it would be seeds since I would imagine that is the to say this in my opinion the most important inputs I mean see that that's what you see grow. And so I would imagine with all the different varieties and all the different hybrids and some are, imagine that they really want to be thinking about the seeds.

But I could stand to be corrected. And I will correct you on that and that's hard because you're a good friend of mine too. So but anyway, we'll still be friends after this. And seeds are probably the second biggest thing. Pesticides are probably the lowest amount of information is used to make decisions on those fertilizers typically have the highest use of data for making decisions. Anyone? Anyone venture a guess. Why?

Fertilizers. I have a. I have a. Go ahead. The reason fertilizers is the highest is because D is not shown.

D would have been machinery. I knew you would well. That for me. Okay, I'll spoil it. Okay. Can I hazard a guess? Yeah. Hazard a guess. What?

I guess because of the clear impact on the yield. Yes, I. And there's a there's a probably a much more noticeable direct impact on yield. And then also I just downloaded the, from Ag Econ, the 2023 crop cost guide that I actually just looked at the first time today. And it used to be you could count on like $100 per acre to fertilize corn. Well, for medium yield now for rotational corn, it's like $250 per acre.

I mean, so that's like what, a third of the variable cost expenses. Okay. So there is some opportunity to save money on that and to impact the elements.

You're saying, okay, more so than seeds. I mean, there's been a number of attempts on seeds, too. We've tried variable rate seeding, we've tried variable hybrids.

There are planters that put different hybrids in different parts of the field. What I've noticed on some of our data lately is that seems to be leveling off, that people haven't seen as much advantage to that as they thought they might say, okay, this is getting nervous. Okay, so we'll go to this one. Question number three, the greatest factor, preventing crop input dealers from offering more precision products and services. And this is couched in the idea that a lot of precision farming or digital ag technology comes to the farmer through an advisor or a dealer. Okay.

And so there's some reasons why they may not be offering products and services for precision agriculture. Okay. And so what is it anyone think on this one, A, B or C, C, and who said C, C, and why do you think that? I mean, I like to use fact like an extension report that comes from almost everyone based on the technology that you've seen, especially from now on.

That's that's absolutely right. That's absolutely right. If you look at it from the farmer perspective, there is often a question as to whether it's going to pay off or not.

And the dealers are sensitive to that, too. But actually, these three here, A, B and C are pretty much equal in some of the surveys that I've seen. And just like industry wide, you just can't find the people to do the work. I mean, that's like clear across the country and every thing. Right. And so yes, that's.

Where we're. All right. For. Yeah. So yeah, these are actually all correct. And we asked the dealers on this is an off of of the crop life survey. We asked them like ten different factors and these three rise to the top and so they're pretty much equal. But okay.

And so I don't think we need to go into the whys on this. I'm looking at the time here and so this is an interesting thing where around the world is digital ag precision ag use the most big farms, little farms like monoculture farms, the little berry farms, not there, not little I should say there's huge like all wind farms and all that stuff. What did you put on this one? A, B or C? Yep. I heard someone. Go have a greatest year by nature or by like capital or. Oh, you know, you're challenging me on that.

The greatest adoption, I should say. But yeah. Where, where is precision? Precision ag in general being used the most? And so I heard someone whisper C my right here and C is correct.

Okay. So I guess my point here is that typically it's large what we call broadacre farms, whether that be a North America, US, Canada, Argentina, Eastern Europe, some that's typically where precision farming on big mechanized farms Australia to lots of it there's surprising a little little precision ag being adopted in on like strawberry farms or lettuce farms or vegetable farms or vineyards in California, Florida or Michigan. There's some of that happening, but not like in the Midwest here. And so one of the biggest challenges of precision agriculture around the world is that these small farm smallholder farms, the Africa, Asia type farms, we desperately would love to help them to do precision agriculture or digital ag.

But it's been really hard to find solutions to help them with that. Okay. So there you go. Okay. 20 to go. So if you're interested in any of this, the reports that I have talked about are posted. There's an economic research service report.

And also my surveys like the last 20 years are posted on the website. Thank you. So maybe I'll take this a little bit from thinking about adoption to some of the reasons that we can think about for helping some of the adoption challenges. So a lot of my work is around this idea of human computer interaction and design, and my focus is on sustainable agriculture. The challenge of adoption is not unique to agriculture, although the reasons are there are lots of reasons why each of us choose to bring technology into our lives.

And so there's an entire family of methods that we can use to try to understand why and how people use technology and really think a little bit more about sort of what the role of technology can or should even be in society. As we start to think about this idea, like, how are people using data to live, work, play and even connect? And so that's kind of the space within which I work. You know, I start with this premise that at the end of the day, we're not trying to design technology to necessarily fix something, but to support people. And it's to support people who are trying to engage in sustainable development.

So you can think about this as digital mediation. The tool is not the end. It's just a means for us to actually engage in building a better future. And so it means that we actually need to reframe the conversation around technology from this being the object to actually being the people that are using the technology. And my IT. So I also come to this work with the argument that all agricultural work is knowledge work, right? We talk about this idea like what does it mean to use information? Every single decision you make, everything you do involves using information about the world around you, whether it's looking at things when deciding what to do, whether it's using a sensor to try and augment your own data input, or even just being able to talk to a friend and ask for some advice. You're always engaging in data, data driven decision making.

You're humans using data to learn something, solve a problem, to make a decision, and that tool is just a vehicle for this type of action. And so a lot of the technologies that we see being built, a lot of the proposed solutions are really trying to shepherd people through this process of moving from just collecting data reactively to being able to actually think about how they can start to make decisions and really try to be able to actually internalize that idea. Right? You want people to be able to become experts or feel like they're experts because things feel more intuitive when we talk about, you know, when I interview folks, especially farmers, I'll hear stories like someone's dad will say, well, you know, I actually don't need to check the soil sensors. I look at the trees. I know that they need water.

I know that the system needs blank and the daughter goes, Well, I don't know what that type of green means. I actually do need a little bit more support because she's still learning how to actually engage in agricultural management. And so in a lot of ways, right, we can think about the design of different kinds of technologies.

Is trying to support people through this path from being able to just collect raw data about the world to actually becoming a little bit wiser about the decisions that they're making. And adoption issues are rampant throughout the stack. You know, does have a beautiful graphic that shows every single piece of tech those out there right now, I'm sure even you in your own lives are flooded with technology.

And we all struggle with the issue of, you know, do we trust the tech? Is it something that's really solving a problem for us? What is it actually doing? So we want to we want and so I couch it in terms of these five design challenges that really I think are barriers to adoption as well as utility. It's really thinking about solving a problem for a real person. Or is it just like something that you thought somebody wanted or you scratching a real itch or something that's in your head? One of the biggest challenges right now is still around usability. So even once you've found a really good problem or important problem to try and address, sometimes you just need to figure out the back end stuff. As you just make the data work, you kind of flex it all together and just say, okay, now everybody start using it and then no one uses it because it's really God awful to use and so like trying to think about like how do you actually like help people use this and feel joy when they're actually like touching this piece of technology? For me, a big part about usability is also about like happiness, right? You want to feel good when you use a piece of technology, not like it's taking something away from you.

Interoperability is, you know, every software engineer’s favorite topic these days or every agricultural engineer's favorite topic these days because just moving data from one place to another is kind of awful. And so that's something that we're really interested in and thinking about. And the other side of this, as then, you know, as we start moving data across platforms, do people trust us with what are doing? Can they see what we're doing with it? As a as a recovering technologist to enter agriculture, I spend a lot of time thinking about this, right? Like I want people to trust me with their data, with a process of managing their information that's deeply personal, even when it's just about the weather on their fields. And the last one, you know, I think about this idea of resilience in many different ways in my work. But in this particular case, it's also thinking about the resilience of technology. Right. And this is where, you know,

I always look at as when I say this to make this comment, right. The thing that we're trying to be right now in agriculture is the spreadsheet. Right. That has stood the test of time. If you can build something that is better than a spreadsheet then you know what, you're probably in good and good luck.

So that's kind of what we try to do with my lab. And we take these three approaches and I mostly share this not as an advertisement for my lab, because I think these three approaches actually help us try to address some of those challenges. The first is this idea of engaging in participatory action research. I don't do this because I think there's money in it. I do this work because I think there is a feature that matters deeply.

And so I'm not just building for a community, but I want to be part of these communities right? These are my friends. These are my neighbors that I'm actually building tools with. Right. So this other part is this idea of actual research where, you know, the last thing somebody needs is for some researcher from God knows where from California to come in here and say, hey, I've got I've got a tool for you. Right? Or to go into some space and like dropship a piece of technology. And so it means that in order for me to actually understand what people's challenges are, I need to actually listen.

And so grassroots organizing is a really big part of trying to then think about like, okay, what research problem should we solve? And I know my colleagues here do a lot of those kinds of things as well. And so that's kind of where we start from the second piece, which is maybe a little bit more science facing as well, is this idea of open knowledge. And I don't just mean open access to data or open access to your papers, but I mean like fair data, right? FINDABLE, accessible, interoperable, readable data. I mean, transparent and understandable data models where you're using language that is not jargony, which even I am guilty of.

And so if you're building a tool using words that real people use, what they're describing, how they plant seeds, and that again, right there requires talking to people and listening to people's vocabulary, their language, consulting with linguists and ontologies if you need to and when you want to with their funds. And then also building open source software, right? The OATS mission has always been dear to my heart. That's what brought me out here, because this idea of being able to look under the hood is something that I find very deeply valuable. And so do folks in agriculture. Right. Farmers have always wanted to be able to repair their own tractors, and that's a really big part of what we should be thinking about with our tech. And the last is just sort of like, you know, the types of things that at least I think we're all moving towards is this idea of not just building for rural economies, but building for resilient communities regardless of where they are.

And the other part of this is, you know, not just thinking about agriculture as production of food for the sake of it, but really as part of being, you know, being part of an agro ecosystem. And so regenerating our environment as we see so many different challenges around the world. Okay. So I spent most of my time giving you so much of that framing, but I'm going to give you a couple of quick examples of how we go about this. So I practice what's known as human centered design, and designers will argue with me for a very long time about why that phrase is also incorrect, because it could also be thought of as community driven design or ecologically oriented design.

You can couch it however you want, but really the process is, you know, you talk to people, you listen to them, you go visit with them, you look at their data, you look at their problems. You figure out exactly why that, you know, that's posted on their fields. You then try to actually bring them together in the design process and you co-create.

I know that you'll talk more about co-production as well, and then you build and refine and you test and you iterate over this. This is not something that is done right. So for me, the act of building and designing technology is a lifelong process. And so it means that we also need to think about things like the maintenance and longevity of technology, especially in the context of resilience. So we use a lot of different methods, a lot of mixed methods. We can always talk about methods another day, but today I'll show you some pretty pictures instead.

So in this particular case, I'll show you the first half of at least our process. And it's this idea of how do you go from, okay, so you run in you like courage. 30 people show, tell, tell you about the challenges they are having. How do you move from that to actually building a piece of tech? So what we do is we'll start by actually visiting with folks and I'll give you some examples from my small firms work.

And so this is the stuff that I've been really interested in doing around small, small to medium scale, diversified fluid environment systems. So think regional food sheds for. That's right. So this is what I see for people like this is their data. This is real data.

This is organic certification data at its finest. And this is like it's the gold standard still, because nobody is really using automated tools for things like organic certification. You go to certified printed out because you don't want to have to write it on the computer. You fill it in, you scan it, you put it in your stack, you put all your labels together, and it's like this giant binder of glory that is like your last three years of of agricultural work. So we look at those things, we bring all those different pieces together.

We start to think about how we can actually map out user flows, data flows, but also technology ecosystems. That's everything from the text messages you're sending to also. Then the advisor that you're talking to is emailing you PDFs as well as soil tests to all of the other potential automatically collected data like sensor data, stuff like that. But not everyone's using all these pieces. Everybody's ecosystem is different. We usually will pull these together to then kind of sort of map out decision topics, right? So how is somebody actually using each of these pieces of data, using each of these tools together? So then ultimately try to make decisions about blank, right? In this particular case, it's about when to go to market, right? So this is a specific user flow for somebody to be able to go from harvest to actually getting it out to different kinds of restaurants.

This is from a study that we did last year. This is a toy graphic. But, you know, the data underneath the hood is fairly real. And so this is kind of the stuff that we start with then be able to start mapping out design pathways, right? So think about this as an image of like the different screens you see on an app, right? We want to be able to sort of map out, okay, from page to page, what does somebody need to do, what data they need to enter, what integration might we need to build on the back end? And there's a lot more stuff in here. I won't go through all of these because I know I have another example of here. But, you know, this is kind of then how we go to from user problems to open source software.

I realized I did that very abruptly because I saw the time about but I can kind of just leave it here end up. So I need to see this. Okay, so this is me. I specialize in science communication and so what that means is communication between scientists and engineers and people who are not scientists and engineers.

So the public and policymakers and people who don't have the same background as the scientists. And so we work a lot in mediated spaces with different media platforms and also and interpersonal communication. So yeah, so this is a busy slide. So the research that's pertinent for me here today is that we're for the last few years we've been working on anticipating responses to novel technologies. So we've done a statewide survey.

We've gone on the ground in southeast Indiana, talked to folks there. These are people in my lab, or Tucker Weiner's my lab manager. And so what we've moved to is this culprit option model, which fits very nicely with Last Talk, right? And so when I first came to Purdue, I was working a lot with the scientist. We have somebody over here in the College of Agriculture and some folks over in engineering.

And so this is roughly the process that I experienced for engineers and scientist. You do? So you have this great idea, light bulb moment, you do some research in planning. You might develop a prototype or a research design. You do some testing, maybe redesign, maybe more testing, and then you roll out the end user. So there's lots of feedback loops in here. To be fair to the engineers, but then usually they bring me in at the end and say, okay, let's make a cool product for you to or let's you know, let's publish In the Prairie Farmer or let's and I will say, you know, can't do it.

And they're saying, Would you have a PhD in this? And I say, Yeah, I do, but here's the communication process, right? So I cannot do the end product that you see there on your right until I really understand who is the audience for this tech knowledge? What are what knowledge do they have about this? What is their belief system? Are there values that might conflict with this development? You know, what do they want to their capability? Is this going to work for farming in particular, who's their social networks and influencer? Who are they going to care about and listen to? Right. And where do they get their information? So, you know, if you're in your tractor and it's driving by itself, YouTubes are quite popular. Radio is popular here in the dairy. So you have different audiences and you need different communication channels to reach those audiences. So we need to do quite a bit of analysis upfront so that we can tailor our communication products to be meaningful to that audience. And if we don't know that audience, if we haven't spent time with them understanding what their needs are, how they would use this technology, you you know, you can spend a lot of money on big campaigns.

Big GM was one of those campaigns. We spent a lot of money on telling people it's safe to say health, safety or food. Sorry. But when you look at some of the research, what they're concerned about is who this is benefiting.

We don't see it’s benefiting us. We see that it's benefiting industry. So so you don't want to have these huge communication campaigns or any communication without doing your audience analysis. So like you, for us, it's qualitative work, you know, really talking to people and getting to know them and understanding what might they want from this technology and how does it fit in your community.

Then we might do a survey to generalize findings. We might talk to other stakeholders. If there's multiple stakeholders like nutritionist, for example, if we're working with dairy farmers, we want to get some picture of the whole social network. Then we would design a message and test it, right? So before you roll out your communication, you have to test it because there's language that means different things to different communities. There's values that they might reject.

Your science just out of hand, right? And now that we can do the communication piece. So in my lab, what we're trying to do is have a co-production process so that in the beginning, when there is this new idea for cameras that look at the particle size, for example, we're already on the ground talking to people and saying, what would this mean for you? How would you like it to function? Would it be helpful? What do you want the engineers to know about your day to day world that would help them design it in a more effective way? So then we would continue to meet with stakeholders as the product is developed, as the technology is being developed, so that the engineers are informed of how can we tweak this to make it more functional for this this space right? So we would work simultaneously through the whole process. And then of course at the end, because we really understand our audience and have the technology and the technology is now reflecting the needs of the community, then we can design communication campaigns so we can educate other people about this new technology, other people who are like the people that we've been interviewing and working with all along. So we've started this work.

Some of the things we learn southeast Indiana about novel technologies and how people perceive novel technologies. So these are some of the big findings, right? So the public sees technology as kind of a double edged sword. So during COVID, it was really helpful to have computers so that your kids could stay in school. And it was really unhelpful to have computers if you had no connectivity like much of Southeast Asia. Right.

And so then, you know, their kids are falling behind. And so, you know, they're seeing it as there's potential there, but it's not necessarily realized in a way that's helpful to us. So they're seeing that their perception is that the risks accrue disproportionately to the end user. So the costs, the risks of so kind of the negative consequences and the benefits are going to large scale firms we're hearing in big companies, but not necessarily to the person who is using that technology. So we're hearing that a lot with big data, actually, that people are feeling spied on, that people are making a profit off of our data and the profits are coming back to them and it's putting them at risk.

Right. So questions from the stakeholders. So this data that's collected in these tractors, you know, is that used for the stock market, market shares, is it going to influence that? And what about how does that influence us that? So there's a lot of questions that, you know, people have a lot of they're also feeling they have very little personal control. So many people we talked to felt like you can't you can't not have a computer. You can't not have some of the newest farm technology because you want to stay either. But you also can't afford it through farms.

And so these decisions, how can we how can we stay even but and not use this expensive technology? And so it's a real dilemma, I think. And and so when we get into governance, people want to be involved in the design. How can I fit better with my needs? How is it going to be implemented? And they're feeling like it's very top down, no control, top down. Here's a new thing.

You either use it or you don't. Often there's no service people that know how to service it in your rural, very rural area. So you incur those costs and now you can't get your machinery fixed. So there's there's a lot of frustration that I think we could address if we were working more closely with these communities.

And so what the research is showing is people want to be involved in this. The only time they want top down is if they're feeling threatened in way that big tech is going to put them at risk in some way. Then they see a need for government intervention. But these are rural Republican communities who don't like the government generally, unless it's to protect them from something that's being imposed and will put their livelihoods at risk. So there there's some nuanced findings that we're getting talking to people. So so by having this co-production model, it is more time, it is more money.

But the end result, that is, you have less rejection of your technologies and they're seen as more useful and more legitimate because they've had feedback into the entire process. Right. And so we're finding this, but the research also is supporting this, that if you want your technology to not be rejected, you need to be talking to people in the development design and then implementation phases. So that's me. Okay. I have to.

Is there one after this? Thank you for attending. Now let’s open up for questions. You saw some of those graphics. I really good. I am glad you were here to see them.

And I'm also very glad that we've recorded this session because I think there are some gems in the comments there. For many of us here, we can design things and do research in science or regardless of the discipline. So I guess not everybody thinks like me? Is that what you’re saying? Not everyone thinks like an engineer. I think we're safe to say that. Engineer, engineering sort of. Here was my challenge as the moderator.

I had prepared some questions. Most of them are, so I need your questions, though I do have a couple down here, but I'm very interested in your questions for this panel about these things, and I'll just make one more comment so that you can get the courage to ask. As some of you know, I've heard the term preto-typing. Some of us have done some briefings on that topic.

It is a very exciting one and it gets to the point you two were making. Pretotyping is a combination of pretending and prototyping, and there are multiple ways to prove that you can just use your favorite search engine and find some free publications about Twitter. But the idea is that you have something that's able to be adopted when you don't even actually have multiple ways of doing that and then going home. Well, am I even got to prototype the right thing because prototyping is expensive and you have to iterate it.

So if you can at least pretotype the right prototype the right thing is at least have something that I think it fits this production model. So but for me, how about your questions? It could be to any specific person or a panel as a group. Yes. But the question, I guess, that relates to all three of your talks, they're fantastic.

Great to see those perspectives then of data processing to get to better stuff. But I'm curious how you deal with those technologies questioning the status quo. I give you a story. I was at a retreat recently trying to sell mapping software, and I talked to a representative of a very large look. We could use this technology to do in very detailed urbanization.

We didn't know pesticide applications, most fantastic, really more sustainable would be great for the environment. Everything the gentleman observed back, well, this is all fine and dandy, but we have the business of selling chemicals. That's number one priority. So all the technology that you operate, as much as the community enjoy all this and not too much as we use it. It's those big companies, many of which. Have made buildings here in the state.

Companies that are pushing actively against adoption. And so how do you address that kind of political struggle, too? TIME You know. So our graduates go work for those really big companies and public relations right there. And so yeah, and they have teams, armies of people that are selling these things, right. And the farmers are aware of that. I mean, there's, they're skeptical about that, but it is a challenge.

So how do you overcome this? All these resources that go into pushing more chemicals when it's at the front of might as you're saying your mapping helps of need not so many chemicals. Right. And so then your audience probably isn't the chemical salespeople. It probably is legislators and the farmers and especially farmer groups.

Farmers listen to each other. You know, they're they're pretty networked and finding out who's the opinion leaders with the farmers, you know, with the with the farm that they all look at and see if that person is adopting something, what do they listen to of their meetings and and that kind of thing. So those might be the people that you want to go to who have.

Ironically, you'll be approaching those companies now. Do you feel they have an interest in buying up start and not have that of competition? And they do. Yeah. Which doesn't help with sustainability.

So I had an interesting experience. The last few years I've been working with one of the top five crop protection companies, farm chemical companies on precision solutions to pesticides and I like one of the first things I said to them, and this is on a consulting basis, I said, Well, why are you doing this? Because this is inevitably going to lead to less use of your products. And they said, yes, but we realize that. But if we don't come up with a solution first, someone else is going to and we need to be ahead of this new curve not left behind with the old curve. And so that was like really refreshing for me to hear that kind of thinking with this company.

It could be refreshing if they're actually doing that for it. That's just their greenwashing. So that's the marketing approach that we're we're sustainable now. But are they actually practicing sustainable? Yeah, and you make a good point, but I was deep enough in the project that they were actually doing what they were saying.

Yeah, that's a plus. It's sort of a separate project, but one of my early projects here at Purdue was exactly that. Yeah, to design and evaluate a system that is less than 10% funded by the insecticide company. So

I'm sure it happens, but it doesn't always happen that they're trying to hide. So I think this is where when we talk about stakeholder engagement, it's also important to remember you're not just we're not just talking about farmers. I yes.

It's important to understand who your ideal user is. So in your particular case, there's sort of two complications, one where there's a value mismatch and another where it's not entirely clear that the user group is completely matched to the product that you're designing. Then the other part of it is, you know, and this is something that we found helpful, is that when we have when we have different kinds of stakeholder workshops, actually also having industry present at the conversation. So that way that they're also hearing what everybody needs to be hearing each other's perspectives and values because at the end of the day of your people too. And so it means that they're all able to then start to see each other's perspectives, understand what the implications of one versus the other are, and actually feel like they're converging on solutions together as opposed to being pitted against each other. And so at least a lot of the work that we've been doing in soil health has included very large companies that I would typically have not thought of as my first call for somebody that might be interested in tools for farmers to be able to share data about soil health.

But they're interested because they also want to make sure they don't get left behind, but they want to love the perspectives and they're open to change. But they need to know why? Because I think that's sort of how they then decide where their investment priorities are. I think ESGs are a nice example of a changing model for the way in which we decide where and how to invest as well.

Let's take another question here. Was just a ready to pop out? Right. Okay. So obviously the common thread that we have all talked about was data. But I think that even in all three of them, there's a lot of trust, even in your level of trust. Right. It's not just which is that just with data, it's the technology that basically gathers that data.

It's one of the biggest questions that I hear across the board for people who are outside doing it, boots on the ground, talking with the growers, is that how do we build trust with them? Right. And so obviously these companies are using technology and precision as a way to kind of do that. Right. But it is a double edged sword.

And so what what advice would you have these folks who are trying to, you know, have these honest conversations about basically saying, right, I don't trust what you're doing, this data. You're going to use this against me at some point. What are you going to tell the person? That's right. Or mercy from that? I'm this amount of money, is it more money or you're going to start raising your prices because you're going to see this this bag of seed or this this is price to own.

But by one piece. So a lot of the cover crops work that we have been doing, it involved. And I'll just give you a little bit of context, right. So there are researchers collecting data about the on farm, right? And so it was a lot of like far more data that was coming in. There was industry interest and using that data, there was an interest in being able to create then government services or decision support tools to help people access government services. And so at the end of the day, there were lots of different data flows that we were trying to think about as we were going through that process, we sort of were noticing that one thinking about data stewardship as a collective was really important so that way you are not just thinking about how you're collecting data, but then how you're also communicating with people across the way, what's happening to the data at each stage.

And so we put together a little trust framework that at least reflected the way in which people are thinking about it. And there's sort of two parts of it was being able to demonstrate how you're trusted with the data, and you would do that by doing things like, you know, being clear about privacy challenges or how the data is actually being used these days. If you download an app on your phone, right, it shows you how you do it.

That's an example of that. The other part of it is this transparency idea, right? So when you're actually collecting data, being able to show people exactly what data you're collecting about them. So cookie pop ups are an example of that, right? We all know what cookies are being collected about us. The other half of that is being trusted with a process. Right.

So people need to understand that your process is not just like grab it and take it and run. And so you actually need to give people this ability to feel like they have agency in the system. I think you talk about agency as well, so I should be able to opt in and out at the bare minimum.

But I should also be able to like export my data. And so this is like very real implications of the functionality you build out, not just portability, but portability. I should experience vendor in for instance. And so that's sort of like all that kind of culminates for me this idea of like generally trying to demonstrate accountability as you're going through this process. And so those are at least those four pieces are the ones that we work with under those two buckets.

Yeah. And if I could adjust to that in communication relationship, that is the foundation of trust. And I'm a little bit worried about, you know, during COVID we went to all these online programs which were functional but much more difficult to build a relationship than if you're on the ground because the relationship is key and always being honest, transparent with your subjects because they want to they want to know if you violate the trust. Right.

It's just like in a friendship with someone that you find out they lied to or a spouse that never it takes forever to come back. So you've lost that trust. So the transparency is key and we talk about huge scientific uncertainty. A lot of these processes, you know, you're developing the technology and all the follow, but being transparent about. So if there's some follow up, what is the plan that you as scientists or engineers have to address that? So people are smart, they know the technology isn't perfect.

Let's first roll out, but they want to know, so what's your plan if something goes wrong with it? Right, that you thought about that, that you're foreseeing any implications that might happen to you? So spending some time building relationships, that's why I hope extension goes back to the in person because that's your it's like a bank account, a trust, right? So if you have positive, positive, positive interactions and there's one minor negative interaction, you still have trust with those institutions and people. If I may add one piece, I think one of the challenges that, you know, when I put my engineer hat back on, my software engineer back on, one of the challenges that we have is, you know, you hear we talk about these as social processes and communication processes, but then at the end of the day, we also need our tools to actually uphold those. And so if we think about software as the codification of values and the codification of how we're actually doing things, then you can actually see very clear transitions to functionality. And I think that's for me the piece that like we don't always talk about because this isn't enough time, but being able to understand exactly which pieces of functionality do I need to build in my tool to be able to uphold these different pieces, whether it's permissions in a database or authentication scopes like they're very beautifully laid out, technical things that you can actually do.

So it's not just something that you should. I think, communicate, but also do in your software at least some percentage. Good. So about half of ag retailers have a user services agreement with their pharma customers.

And so that to me is part of the trust thing. I guess it's sort of way like a prenuptial or something like that and you know, that's who owns the data or whatever. You have a common understanding that that to me is a foundational thing. Like for instance, one of the examples of things is like if an a retailer is on a farm that is owned by this party but rented by this party, then the owner has the data.

Does the renter have the data? Does the retailer that's putting all the fertilizer have the data? So there is those questions of that can be ironed out and on campus here the trust thing for me I are I often worried about that a lot but it's really come down to be pretty simple. I just don't work with people I don't fully trust and I don't work with companies I don't fully trust. And fortunately in this room, I think I pretty much trust, fully trust everyone.

So thank goodness. We have passed the Erickson litmus test. That’s something to write home about.

Just don’t put that on your resume necessarily. Well, I wanted to ask the question, though. As a user of technology, I see all agreements and they're like ten pages.

It's always like, read this plug. Yes. And go. It's burdensome to try to do that. So, you know, how how is a user develop these things? Can you make this a little bit more apparent to me without having to read a ten page document what's going on? So for me at least, this is a usability challenge as well, right? So when we think about the way information is presented to people, I don't meet the 20 page terms and agreements and I'm downloading the software. And so there are different design patterns that are recommended to be able to try and actually like color around these issues. These are not for you as a user.

These are not things that you should be doing. The onus is on the technologist and I think technologists taking the responsibility of choosing design patterns, including things like TLDR like too long only by having a summary statement, right? Or having there's a project that I'm affiliated with whether you're talking about like human readable, legal these right. For me, I read an open source license. I'm like, man, I don't want to read that. Like, I need to figure out how that will go around my piece of code that I'm going to release into the world and then I want to be able to tell you what I'm going to do with your data. But if I don't even understand that legal document underneath, that's a barrier.

And so there are different projects in the space to talk about. So that understandable ability piece as improving the usability of different kinds of privacy preserving features that I think we at least technologists talk a. Lot about that one needs to do things on that. But I'm more interested in your question. So I'll kind of talk about this where the adoption is largely on the farmer or the company supporting farmers, but is there potential for there to be like a consumer side to this story to where there's either space created for farmers to experiment more incentives or something that can help drive some adoption.

Through an experiment with practices? Yeah. Yeah. If I'm trying to produce carrots at a certain price, yeah, maybe there is a technology I'd like to try for a year or a season and see how it goes. But yeah, I would have to eat that cost of doesn't work out. Yeah, I at least look at incentive programs as mechanisms for trying to at least make it easier for people to do risky things.

And I don't just mean cost share for larger, more common commodities, but more there are like that. So I'll give you a couple of examples. Right. So like with the CSA, the commodity scrap came out and there were like a whole bunch of incentive programs that are going to come out of that.

And series has so many different conservation assistance programs, there's so many different assistance programs, but even knowing where to find those sorts of support structures to then be able to like be risky or try new things is really hard. And that applies for everyone from carrot growers all the way to food growers. And I guess there's also sort of everything in between. So I think digital twins and modeling and all that help with this too.

I don't know. There's not really be. A way to to estimate with some sort of. Yeah, yeah. The likelihood of success here. Because I know like those economists do these Monte Carlo simulations and all this kind of stuff all the time. It takes a good, thick, good model.

Yeah. And then my colleagues reflect uncertainty. Honestly, what will help with our trust? Like, here's, here's this and we're this. Sure. You know, with its success or that sort of thing, do that. And I think part of the challenge is that right now, models are not robust enough yet, in my opinion, for certain kinds of areas to accurately be able to help you run those of scenarios.

And so for me, that's a really interesting research, right? So that's something that I think we should be working on is trying to be able to create models that help you to do predictive and perspective analytics in addition to. Right, the usual. And so there's an open space there, but then also trying to think about like, well, okay, what happens if I adopt this a program in theory on my bank account, but then also in practice on my soils or whatever or my market thing.

Is often done for the virtual budget side by side scenarios. What is that? Some of our restrictions, I. Was thinking earlier, could you guys work with Purdue on their user interfaces like some of the businesses? To some extent. So you have no idea how to fix this sometimes. So now we're talking with designer about user interface. Okay, any it's not just.

Your. I just get frustrated. What a waste of time to implement so many systems that are not efficient.

But I know one point or another important point earlier about the sort of the power of extension and all of this as well. Right. As we're thinking about like who tells you what kind of practices you can play with or he tells you where the assistance programs are that you can engage with to try something risky. For me, I always look to extension and advisors of growers and other managers of systems as the purveyors of that type of information. And so empowering those groups, I think, is a really important piece even with technology and also getting better interface, I think with extension and the scientists here right.

My opinion is that the software requires the user manual. Maybe it's not as user friendly as it ought to be. It ought to be reasonably intuitive with, of course, the details you need to watch the videos that your.

Filing might look for reported. But it has to be structured. Okay. One final question before I ask it. Let's take is three for some really good first one, maybe if you have a quick answer, it would be great. How about instead of just advice to the designers and the scientists, a little bit less to adopters? So my question is, how do you how what advice do you have to people who are faced with this thought about how will they choose the right one or the best technology or the best solution? What should I be looking for to choose this instead of the top of mind? Because I know the territory you got to know.

Like with the it's for corn and fertilizer, you got to know how corn response and how soil varies. And that's where I think for a lot of us, we don't fully understand the whole system. Don't engage, get involved in the process. But people you know, people there are lots of opportunities to actually inform the design process for certain kinds of tools, especially the open source role.

And so actually coming in and voicing your opinions I think is an important part of it, but then also trying to find ways to educate yourself about the options that you have and matching it with the tools that you need. And then just try stuff. I download every app and then I decide which one is better.

I have to go through. I guess I would say, you know, I would say don't put the consumer in that position because you have designed something that's not necessarily tailored to their needs. Right. And so it would be much better to understand in the design process what are their needs so that you don't have to impose something in the system. They're experts in their own world.

And I think as scientists we forget that. So we have the expertize in engineering, in science, but they have the expertize in their daily lives and those have to go together. Yeah, I guess what I was wondering is I am a consumer and I have multiple things to choose from, but I really can only as one. How do I know which one? So because there are multiple companies, multiple researchers generating alternative solutions that I actually want, that I don

2023-04-08 19:11