Technological Revolutions and Art History, Part Two: Spyros Koulouris

- Okay hello? My name is Louisa Wood Ruby. I'm Head of Research at the Frick Art Reference Library, and welcome to part two of our four part symposium, 'Technological Revolutions and Art History.' Co-organized by the Frick's Digital Art History Lab and the Museum of Modern Art. It is the second this one, in a series of symposia Frick is holding to explore how recent advances in technology can affect methodological change in Art Historical Research.

The first was held in Spring of 2018 and was an exploration of ways to harness existing tools in computer vision, science for art historical research and advise their development. Videos of that event are available on the Frick's website. Part one of this year's symposium, a four-part symposium, took place on October 15th and focused on the reasons for the divide between science and the humanities in the late 19th century and what it means for us today. For Art Historians in the 21st century, this divide is only widening as some scholars embrace technological advances while others remain unconvinced that computational techniques and tools can bring meaningful changes to the field. These symposia hope to change that trajectory.

Presentations today, and you see the list on your screen there, we'll examine how the invention of photography impacted the study of art and how current technological advances have been able in recent years to promote (indistinct) with new developments in the field. It will end with a discussion, an opportunity for the exchange of ideas for the future. Videos of both the October 15th event and this event, will be available on the Frick's website in the coming weeks. On your screen, you can see a list of the... no, we don't have that on our screen today but if you go to our Frick Digital Art History Lab website, you can see a list of the titles and links to sign up for the rest of the series, that takes place on January 14th and March 11th. Perhaps that, We can post those in a minute, or I'm not sure in the chat.

Also in the chat you can find a link to the speakers' full biographies and abstracts of their talks. There will be a question and answer period at the end today, so right at the end from about 12:50 to 1:00 PM. So please write down your questions. You can put them in the Q and A box that you see on your screen, (clearing throat) and the Q and A will be run by Samantha Deutsch and myself both from the Frick. So feel free to start with that. Today, it is my pleasure to introduce Spyros Koulouris, who is the photographic archivist of the Biblioteca Berenson of Villa I Tatti, The Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance studies, a center for advanced research in the humanities located in Florence Italy.

So many of us are very jealous that he's there. Today, he will speak to us on how the famed 19th and early 20th century art historian Bernard Berenson, realized early on the revolutionary implications of photography for art history. And now I'll turn you over to Spyros. - Hello, Louisa, and thank you for this introduction, and I think you can see my screen right now. And thank you to the Frick collection and the Museum of Modern Art, for inviting me to talk to this symposium about Berenson and photography.

Talking about art history in the context of technological revolution is something that archivists love doing because they believe that everyone is thrilled to see images like this when attending a seminar. Well, although photo archivists believe this image with all its complex data and the links between them represent their work, most of the times they have to resolve less sophisticated issues like the ones you see here. Berenson and photography is a topic that often comes up when talking about art historical photo archives. He was the one of the first art historians to create a large collection of photos.

But what about his thoughts on technological development of photography? What you see here is the picture of a black hole, unveiled in 2019, by the Event Horizon Telescope project. It may be considered the latest evolution of taking photos, as it is actually the first ever image of a black hole. This is a silhouette of the galaxy called M 87, and being able to see it is considered a great technological advancement that a group of scientists obtained by using a network of telescopes in different parts of the world. Now, the question you may ask is what Bernard Berenson or photo archives have to do with it? Well, among the many different photos that can be found in the Berenson archive is a group of 12 images of our galaxy.

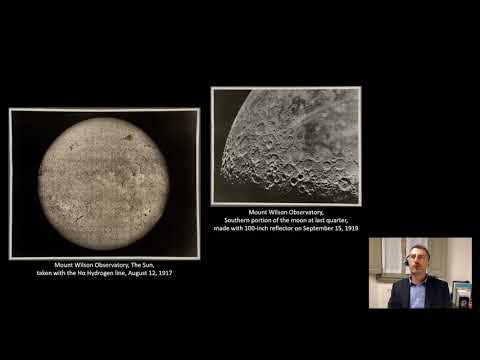

As we learned from Nikki Mariana's notes, the images were sent to I Tatti by Belle de Costa Greene, the librarian of the Morgan library in the summer of 1926. Unfortunately there is a gap in the rich correspondence between Bebe, as his friends used to call him and Belle Green, which doesn't allow us to know the complete story of this acquisition. Since the development of photography, there have been several tentatives to capture the moon and the stars. In this case the photos were taken from the Mount Wilson Observatory in California, between 1917 and 1920. It is fascinating that Berenson was interested in this kind of reproductions, and I believe it is a demonstration of his interest in potential uses of photography to study both art and science.

Here you can see the photos, of the moon and the sun, and this is the image of a Spiral Nebula, one of the first photos of stars in other galaxies, obtained by using early 60 inch telescopes. I'm afraid that considering my poor knowledge of astronomy, it's better note to go more into depth in this topic. So let's go a few decades back, and see when and how Berenson got first interested in photography. His biographer, Ernest Samuels, reports that in 1884, when Bernard was only 19 years old, he and his sister Senda went shopping in Boston for photographs to decorate his room.

Later in 1888, Bebe asked (indistinct) from Senda, to buy photos of paintings in Dresden. By the time, art books were often illustrated with two photographs or from mechanical prints, and the market of photos depicting artworks was already very big as more and more people wanted to obtain copies of their favorite artworks. So all major European studios were publishing catalogs to advertise their work and that way they made the circulation of photos easier. Alinari, Brogi, Anderson in Italy, Braun in Paris, Hanfstaengel in Munich, are some of the photographers that made those reproductions.

Thus two years afterwards, in 1890, Berenson express publicly for the first time the importance of having good photos in the journal Donation. In this editorial, he praised the work of the Milanese photographer Carlo Margozzi, for the perfect reproductions made of the Poldi-Pezzoli collection, and hoped he would continue photographing other collections. In his first steps as an art historian, Berenson was greatly influenced by Giovanni Morelli and his method of connoisseurship. This consisted of using clues, offered by details in the paintings, like hands or ears, in order to identify its author. Although we know Morelli owned photos of artworks, he didn't make any reference on them in his writings.

Regarding the illustrations of his books, in the 1889 preface of the "Italian Painters", he mentioned that the readers that intend to make a serious study of the artworks should, I quote, "go to the works of art themselves." end of quote. Berenson tried to refine Morelli's technique and employed photos in order to improve his memory or to study paintings that he wasn't able to see in person.

He started collecting photos that collectors, photographers and other art historians were sending to him. That was an excellent way to compare artworks that were physically far away from each other and also allowed him to further reinforce his connoisseurship skills. A first important contribution on the topic of artwork reproductions was made by Berenson with an article written in 1893, that means he was then 28 years old.

and the article was titled "Isochromatic Photography and Venetian Pictures". At the same time, he was preparing the first edition of his "Venetian Painters of the Renaissance" published one year later in 94. So he was very much aware of the difficulties when studying Venetian painting In the article he made some strong arguments about the need to use photographs when studying the old masters, I quote, "if most people are still incredulous "about the possibility of giving a rational "systematic basis to the criticism of art, "it is largely due to the fact that until very recently "any accurate comparison of pictures "was out of the question. "The hitch in connoisseurship has always been in comparison. "In the days of slow travel, "when there were no photographs, "of old pictures to be had, "the connoisseur was obliged to depend largely upon prints" end of quote. In the article, Berenson admired the work of both Alinari and Anderson for undertaking the difficult task to photograph paintings in Venice.

Berenson argued that the paintings were in many cases in very dark churches or in rooms with very strong sunlight, making it possible for visitors to study them. For him, there have been two major technological developments that revolutionized art history; photography and railways. The possibility that these gave to travel faster and easier in order to see works of art around the world and the possibilities to make comparisons between artworks. Berenson noted that both Passavant and Cavalcaselle, were not able to use photography. And that Morelli was the first critic who made systematic use of photos.

He also pointed out that the reason why Morelli focused on drawings and on Etruscan painters is because photography could only give the outline of Venetian paintings and it wasn't capable of rendering the colors. This is something of which John Ruskin was aware of 20 years earlier. I quote, "I tremble to think what would happen "if photographers were able to take photographs in color, "seeing what mistakes they make now, when they have all the monochrome to deal with" end of quote. Berenson also described the distortion of the colors in what he called ordinary photography, in which blue becomes white, while red and yellow change to black. He also expressed his disapproval of what was the common process of retouching the photos in order to make them appear more close to the original.

The new technique of Isochromatic photography was already adopted by photographers like Braun and Marcozzi. Thanks to Alinari and Anderson, it was used for the first time in paintings, all around the Veneto region, making it possible to review attributions of Venetian artists. Berenson praised both photographers but made a special mention to Anderson because his photographs, I quote, "are the pictures of themselves on a smaller scale" end of quote.

An immediate result of Berenson's article, was that the new edition of Morelli's work "Della Pittura Italiana", published six years after Morelli's death in 1897, included a large number of reproductions not available in the previous German and English editions. As mentioned in a note of the introduction, the reproductions derived from Isochromatic photographs of Anderson, Brogi and Alinari. Color photography continued being one of Berenson's interests, and he kept himself updated on the progress that took place in the first year of the 20th century. A small collection of about 100 glass autochromes, documents his curiosity to the technique invented by the Lumiere brothers Auguste and Louis. The new process was first marketed in 1907 and offer the possibility to have color photography before the advent of color film.

Initially Lumiere film color and then the multi layer subtractive color films of Kodak and Agram in the 1930s. 47 of the autochromes reproduce the art collection of I Tatti, views of the library and the gardens, as well as some pictures of Mary Berenson. As Giovanni (indistinct) has pointed out, the presence of Nikki Mariana in the image you see here, allows us to date this collection between 1919, the year when Nikki arrived at I Tatti, and 1920, which is expiration date, we find on the containers, on the boxes, of the autochromes. The different formats of the remaining 50 autochromes and the letter written by Mary suggest that these were made earlier, in 1911 approximately. That means that the autochromes were commissioned in different moments, demonstrating Berenson's interest, in the development of this new technique through the years.

Berenson was interested in owning several photos of the same painting. We know for example, that he organized many photo campaigns to document his own art collection. Among the photographers involved were Harry Burton, Vittorio Jacquier, the Foto Reali studio, and others that haven't been identified. The series of images that you see is a selection of photos that he commissioned, depicting the same painting Giovanni Bellini's Madonna and Child. And it highlights his desire to investigate the possibilities offered by new techniques in his belief that each photographer and each print may provide useful visual information. In his writings he often referred to the use of photographs he made.

In the preface of the "North Italian painters of the Renaissance" published in 1907, he informed readers that although he has examined all the paintings mentioned in the book, there were a few exceptions of paintings attributes the painter only by studying them through photos. I quote, "I have however inserted, "on the inspection of photographs, "some few pictures in public places "and relatively permanent private collections "without having seen the originals" end of quote. After (indistinct) he specified that this can be done only in cases of very good photographs made by talented photographers like Braun. Making a judgment based only on photographs was definitely not something common for the time. But this demonstrates the high value that Berenson gave to photography for its reliability and validity. Indeed, a few years later in the new edition of the "Venetian Painters", he expressed once again, his belief that it is thanks to Isochromatic photography and to rapid transit that connoisseurship became, I quote, "something like an exact science" end of quote.

By that time, it was obvious to many scholars, the need to create reproductions of as many artworks as possible. The Arundel Club was the society founded at London back in 1904, whose main tentative was to encourage knowledge of European masters by reproducing artworks in private British collections. Berenson tried to promote the Society's activities. He wrote an article about it in the journal donation.

He became a member of the society and contributed to it financially. It is in this context that we should consider photo campaigns that Berenson organized himself. There have been recently identified approximately 80 prints in the archive, by the photographer Harry Burton made between 1900 and 1911. The photos were commissioned by Berenson in order to study the Venetian masters, as he was preparing the updated list of the "Venetian Painters". They include reproductions of paintings in various locations in Veneto and Puglia.

Harry Burton continued working for Berenson and other Anglo-American art historians in Italy, such as Frederick Mason Perkins and Maud Cruttwell. Berenson ideas on Isochromatic photography had a strong influence on the young Burton who became early interested in color photography. In the following years Burton either as a field photographer in Carter's team during the excavations of Tutankhamun's tomb, or as a member of the Metropolitan Museum's expeditions in Egypt, he was able to further experiment with new materials and techniques such as cut film and color transparencies. It's interesting that when Burton moved permanently to the U.S he left his negatives of Italian paintings in Florence.

Some of the glass plates are now part of the Gabinetto Fotografico of the Uffizi Gallery. While the biggest part of them was acquired by Helen Frick, through Mason Perkins, and these are still in the Frick's photo archive. For Bebe, the Venice project seems to have been his first attempt to organize a large photo campaign of this kind.

From that time onwards, he became involved in many similar projects. The most famous one was the association he created in the 1920s with the Italian art historian Pietro Toesca, with whom he served the same desire to reproduce unpublished illuminated manuscripts. We don't know a lot about this society, it is mentioned however several times in the Toesca-Berenson correspondence, we can think of it as an Italian version of the Arundel Club in which, several partners, art historians, collectors, and others, contributed money in order to share the costs of reproducing the manuscripts. Now, Berenson was a scholar with many interests and was fascinated with the Mediterranean as an area where many civilizations flourished. On the other hand, he was also curious to meet other cultures beyond Europe and to open his horizons in Asian and pre-Columbian art. And this is reflected in his collection of artworks, books and photos.

Quite early he got involved in photo campaigns out of Italy. The most well-known case is the one of Archibald Creswell, the British Islamic architectural historian, that's traveled all around the Middle East, measuring and photographing monuments between 1910 and the 1920s approximately. As it turns out from the correspondence between the two men, Berenson admired Creswell's work and sponsored him to complete his ambitious project. But Berenson took part in another photo campaign, this time with the Harvard professor and photographer Arthur Kingsley Porter. The Berensons were tireless travelers and in 1923, they undertook a three month trip to Greece with the Porters. During the trip they visited and photographed a large number of Byzantine monuments.

Now, the great value of both of these campaigns, stands in the fact that the photos were taken by the scholars themselves. Indeed they can be found details, usually not shown by commercial photographers and images of lesser known Byzantine and Islamic buildings. For instance, here, you can see that scaffolding used by Creswell to photograph the mosaics, the details of the mosaics in the great mosque of Damascus. and in the next image, you can see that specific detail, that specific mosaic photographed from that scaffolding.

Before closing this presentation, I would like to make a last remark about the role of photographic prints in organizing the information related to artworks. Berenson included a lot of metadata on the verses of the photos and the arrangement of the entire photo archive allowed him finding easily all kinds of information. While in his publications, the artists appear in alphabetical order. In the photo archive the same artist, can be found in chronological order, and in other adaptations he made when visiting museums and private collections are organized in geographical order. So this elaborate system of organizing metadata, permitted him to cross-reference both textural and visual information coming from different sources.

There is no doubt that if Berenson was alive today, he would have been excited to see all the new tools that art historians have available. New technologies provide all what he most wanted. Faithful reproductions of the originals sophisticated software to compare different artworks or several images of the same artwork. Easily retrievable metadata and last but not least, the possibility to make adaptations on the images.

And this is why I'm showing you this IIIF viewer screenshot. It's not to talk about the reasons why, Vincent Van Gogh cut off his ear, but to highlight how this image combines the technological capabilities of the IIIF manifest, with Giovanni Morelli's method of studying art. In the context of what is called Fourth Industrial Revolution, we can hardly imagine what effect with digital humanities and new technological developments like artificial intelligence and 3D printing may have in art historical research. As Berenson wrote by the end of his life, "representing something is like compromising with scales, "whether visual, verbal, or musical."

Under this light, his photo archive may be seen as a compromise to organised knowledge. A sort of telescope that Berenson used to capture what was still unknown in art history research. And that was all for me. Thank you.

2020-12-22 18:11