Chapt. 7 Public Financing Costs

Okay. We, are doing. Chapter seven here. Guess. It's kind of a tradition, now, although. I. Do, have my bright. Green shoes on today running shoes so we're gonna go quickly today. There's. A lot of content, in Chapter seven of course since. This is recorded, you. Can always go, back if you didn't understand something. Or. Contact. Me as. Well and get an additional, explanation. That's always an option for you for sure. But. With a lot of content I'm going to try and squeeze it into I like to keep these at 45 minutes or less if I can I'm not always successful, but I know it can, be hard to watch. A. Lecture. Once. It gets more than that a lecture, that you can't necessarily interact, with so. In. Chapter 6 to remind you we talked about some, of the benefits, to Pope, financing. For the most part and, a little bit of the structure about how we might measure potential. Benefits, and. If it makes sense in terms of economic impact. So. This, chapter starts, talking. About. This. Idea of opportunity cost, right so. The. Dodgers, this. Was a big deal in the mid 1950s. When the Dodgers, actually, left Brooklyn. And the reason it was a big deal on baseball was. Because. Well. For one baseball. Was very. Stable, Major, League Baseball was very stable for, the first 50 years of, the 1900s. But. Then the. Braves moved, from Milwaukee down. To Atlanta. The. Browns moved, the. A's moved, as well but all three of those franchises were, struggling, so financially. So, the reason that the Dodgers were different is that they, were the most profitable, team in. The National League when. They moved and. They. Accounted, for almost half of the National League's profits. They, were well, supported. Within the community, of Brooklyn, so. Why did they move well, like, I said, starting, out. Opportunity. Cost even. Though they were doing really well in Brooklyn, in, comparison, with other major league teams the opportunity to move out to LA, where. There was twice, as many people. I was about a million people in Brooklyn at the time 2 million people in LA, the, cost to them not moving, the money they were leaving on the table was. Just too much and so they moved out there they also convinced, the Giants. To. Move out to the west coast as well San. Francisco obviously. But, also another New York team moving. Out there because, the opportunity, cost of staying in New York was just too great. Now, when we talk about franchise, movement, um in, our. Leagues here in North America an, important, point is. That. Some of our league's most, of our leagues include, one, or more Canadian, teams, an. Exchange, rate can, make a difference here in terms of franchise. Movement, and publicly, financing, teams, so. Keep. In mind that, any of these, Canadian. Teams they're. Getting most of their revenue in Canadian dollars right think about how sports teams make, money right, you've got sponsorships. You've got. Merchandise. Sales you've, got ticket sales. You've, got broadcast. Agreements. And. Legal, one-off oh concessions. And other. Stadium. Revenues, so. A lot. Of that inflow, except, for with the exception of perhaps the broadcast, deal which is. Sometimes. It's a kanay tiff it's a team in Canada other local broadcast deal would obviously be with the Canadian station but the national broadcast deals are negotiated, in American dollars but all that other income, sponsorships.

Ticket Sales, merchandise. Sales that's. Revenue, and Canadian dollars if you're a Canadian team right, however. All. Of these, Canadian, teams pay their players in u.s. dollars, which. Is their biggest expense, right, so. They have to take that, revenue. Money exchange. It for US, dollars and, then pay, their players, the. Reason they all pay their flows in u.s. dollars is they don't want to be at a disadvantage of free agency right. So. The problem is that if. You're taking. In revenues. In one currency and your expenses, are in another, your major, expenses, in another currency, fluctuations. In the exchange rate can really, impact, the viability of, your business and the profitability, of your business, in. The book gives this example of 2011. The Canadian dollar in US dollar were about. Equal. But. Ten years ago, the. Canadian dollar was, much much, weaker. So. When a Canadian from. The Canadian dollar is weak compared. To the US dollar. That's. A problem when your revenues coming in in Canadian dollars because you when you convert it you're not getting as many US dollars, for that so, you having to convert more Canadian, dollars just to get the same amount of US dollars and, that's why you saw 10 years ago. The. Canadian, teams. Speaking. About, Hokkien in particular. They. Just didn't have the same revenue. Sources to pay, payroll and. They became less competitive, on the ice because. They were less competitive, off the ice and we saw, the. Winnipeg jag Jets, is just one example moving. To Phoenix. We. Saw. Who's. The other teams. That move we saw the, Colorado Rockies, I think they were the Quebec Nordiques, they. Moved to Colorado and became not, the Rockies excuse me to avalanche. And. There was one on their movement. One. Of the teams was. In. Canada, and moved to become the, Thrasher's, I don't remember whether it was actually. Robber. But then. The. Canadian dialogue gets a lot stronger versus, the US dollar over, a 10 or 15 year period and, then we see actually, an American team moving to Canada, with. The Thrasher's moving, giving. An NHL, team back to Winnipeg in. 2011. So. We've. Talked a little bit about market. Power and kind of who has. The. Power in a marketplace, and how monopoly can manipulate that, market power quite a bit we've. Spent time talking about how North American sports leagues because. They're closed leagues and they limit, the number of teams that creates, this power, in the marketplace. It. Certainly. Increases, profits. Because they can extract, sort. Of they. Can extract financing. From cities right, that, are bidding to try and host teams. It, also enables, them to kind of increase competitive, balance within the league itself, because it's a closed league so because they have more profits, they, can spread those profits around and it can help them increase competitive. Balance you saw, that. Kind, of argument in the CNN article that that was posted on blackboard, that you read for I think it was your first discussion board opportunity. That. Compared, the European model that's not close leagues to our model in the u.s. that does have closed leagues. But. Even though we have closed leagues. Sometimes. That market, stranglehold. Er that market power is broken, a little bit in the leaks do agree to expand, usually. For one of three reasons we already talked about one. If. The, marginal revenue that a new team can bring in exceeds, the marginal cost, of spreading the revenues over that additional. Team. Then leagues. Will expand. The. Blue jackets are a good example, of that in the Minnesota Wild as well when. They came in. Another. One is to prevent the formation of a new league, right, so if you're going to restrict, the number of teams and, we talked about this before too and you have markets. Without. Teams, but, there's, the demand for teams that creates an entrepreneurial, opportunity, for rival leagues. To. Form, and put teams in these markets, that don't have, professional teams. And. Eventually. Become a viable competitor to, the current, dominant. League so. We. See the dominant league will try and expand into markets. Where. Where. They. Can probably. You. Know a market that can probably support a team because. They, want to leave a few markets, maybe without teams to continue, that strong marketing, market.

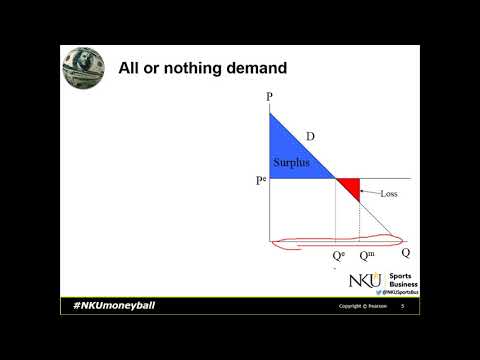

Power Where they can the owners can negotiate with, cities, that don't have teams. That could probably support a team and they can sometimes, extract, more out of their own city by doing that so that happened here Cincinnati. With the stadium deals, but. They don't want to leave so many markets, open without, teams that a new league can form so it's kind of a balance there right. Another, reason is to appease, Congress, like sometimes, Congress likes to meddle in the professional, sports and that, antitrust, issue is always. Sort. Of right under the under, the surface. Several. Decades ago a senator, or a congressman from. Louisiana. Was starting to needle. The NFL, a little bit about antitrust. Issues and to. Appease that, congressman. The NFL put, a team in, Louisiana. In New Orleans that's how we got the that's how we got the Saints in the NFL, and. There's. Some limitations, to this market, power to so cities. Really. Cleveland. Is unfortunately. Close. To where I grew up it's not unfortunate. That it's close where I grew up but Cleveland. Unfortunately. Committed, this error in terms of negotiating, power they kind of gave up their negotiating, power when. They lost the Browns because, they passed legislation to. Pre-commit, funding, to, an expansion, team even, before an expansion, team was granted, right. So they sort of set the, bar pretty high in, terms of expansion fees. For. The NFL itself, because, they approved, all this funding the NFL knew the money was there so the NFL of course charged them an exorbitant, expansion. Fee because they knew that the money was there because. Cleveland. Had already pre committed it. Another. Limitation from the league side is when, if you put teams in all the markets that can support, a. Team, then, you don't have any empty markets, to sort of leverage against, right, to, say hey if you're not willing to pony up and support your team in this market then that team can move to this other market that can probably support, a team right. But that argument is not gonna work if all the markets, have. A team right that argument. Doesn't work in the EPL, for example English Premier League because, it's. A closed league or excuse me it's not a closely, it's an openly so. Any market that can support a team a team will eventually, be, formed by an entrepreneur and work its way up through the levels of. Professional. Soccer and England and could eventually make it to the Premier League. And. Then there's regional appeal right hockey's the best example of this that limits the, market power of leagues somewhat. Because. Hockey's not more popular in the south or, in, whether climates, it limits their power a, little, bit because it has. A pretty strong regional appeal. NASCAR. Also. Has that same issue although opposite. Regions right NASCAR, very popular, in the southeast. Some, parts of the west but it's had trouble sort, of catching on in the north and specifically, the Northeast. So. Another example. Here, I think the book uses NASCAR for this example to is not. Every, product. Is. It. Able. To be sold or, provided. In various. Quantities, where we can have a whole, continuum. Access. Access. Excuse. Me. Along. This line some, products. You're, either gonna get all of it or you're gonna get nothing right. And. The, book uses the NASCAR Hall of Fame for this example and that's a pretty good example right, the. NASCAR Hall of Fame is when, they were deciding where they were gonna locate, that. Hall of Fame they sent out a request for Proposal, two cities, and. The cities have the chance to bid on what. They were gonna provide in terms of maybe tax breaks maybe property. For. The project. Maybe. Some, municipal. Bonds, or loans, at, a very low rate to help NASCAR. Build. That property, build. The Hall of Fame and host. All of. Memorabilia. In the Hall of Fame, but. Those that request for Proposal, was, in all-or-nothing, situation. So. They were saying you're, either going to take the whole Hall of Fame and at. This dollar amount or you're gonna get nothing right so. In cases like that where a, product, is provided, at a specific quantity, right, the, equilibrium.

Point For that quantity could, be. Something. Like this. We're demand. It's, here. But. The supply. Line. Is vertical here it's all nothing of the price line excuse, me. We've. Got this surplus. At this price. However. In. A monopoly, situation, where it's all or nothing which of course the nascar has. Monopoly, in that example. Nascar. Says hey. You've. Got a bid on this quantity, right. So even though this might be the optimum, quantity for the demand. That. Exists in the marketplace we're. Only going to give it to you at this quantity out here, right. Well. This is beyond the demand line you see that right now. There's. Still a consumer, surplus so the people that demanded, it, even. More at, an even higher price or even more of an investment by the city this is still a surplus right, because they're only having to pay at this particular. Level, however. They're getting like this, huge quantity. It's. Much more than, is what demanded, or at least somewhat more than what is demanded, this, becomes a loss situation. The. Consumer, or in this case the city is the consumer, in, the example, of the NASCAR Hall of Fame it's. Still going to buy at, quantity. And quantity. Monopoly. Here. As. Long as this loss is. Smaller, than. What the. Surplus is that. They're gaining right. So. They're willing to absorb some sort of loss. In. Terms of quantity, that they're getting that they don't really want but they're gonna have, to house all that merchandise right they get a larger, Hall of Fame than they actually wanted. But. They'll, take it, because. With it comes, a, degree. Of, demand. Surplus, as well at that price. So, like. I was just describing the max quantity. That. The consumer, of the city is going to take in this case it's all the way until that. Loss becomes. Equal, to the surplus and then they're not taking any more right, then it's just too much it's, just too much stuff so in. An all-or-nothing, demand situation the quantity is essentially, set right, and, the. Consumer. For. The city whoever's paying for, it has to decide. Do. I want to pay this amount for. This much product and, even. Though, it might be more than is what demand what is demanded. Which. Means I'm going to have to I'm gonna have access. I'm. Going to continue to take that until, it becomes too, much access to, where it just doesn't justify. Me taking it. At. That particular price. Present. Value. You. All, I'm. Assuming, have had some sort of finance either in high school or perhaps. Here at college where you have some understanding, of present. Value and future value this. Is important, in terms of public financing, because a, lot of this commitment. Of. Dollars, for stadiums, and for teams or, future. Tax breaks right, our, benefits. Where. We're. Measuring benefits. In the future that. Might come but, we're gonna have to outlay, funds now right, so, we have to think about this what's the present value of these future. Benefits. So. At a very basic level. Would. You rather have $1 right now that, I hand it to you or would you rather that I gave you that dollar tomorrow. Well you'd rather have it right now hopefully, you didn't have to think about that very long right, because. At any positive, interest, rate the, dollar now is, more valuable to you conceivably. You could invest, that money and. Even. A day from now it would be worth just a little bit larger right, a little. Bit more. So. How do we calculate that. The. Value of $1 today in a year is just the, dollar times.

1. Plus whatever, the return rate is the rate of return is or the interest rate that you're going to get on investing, in your money right. The. Calculation. If you want to know in. The future I want to have $1 right. Say a year from now I want to have $1 how, much money do I need right now I take that dollar and I divide it by 1 plus the interest rate right. Simply. A little bit of algebra, from that equation right above it right, and that gives us how much money do I need now, to. Have a dollar a year from that all. Right, so. Let's. Expand, this out a little bit so there you see an equation here. That has given you the present value of $1, in two years right, so I give you a dollar now what's, it going to be worth in two years. $1. Divided, by one plus the interest rate square. So, now let's expand this out a little bit more. So. Here. We're thinking about. There's. A stream, of benefits that, are going to happen right so this b1 is the benefit, in year one this. Is the benefit in year two the. Benefit, in year three, right, so if I have an annuity, that, is going to pay me a hundred dollars, in. Year, one a hundred. Dollars a year - a hundred, dollars in year three all the way out to t, years. Or however many years this, is how I'm going to calculate it right put. That hundred, in here divided, by one plus the interest rate that number. Plus a hundred, dollars a year - divided, by one plus the interest rate squared, plus. One, hundred dollars in year three divided. By one plus the interest rate here three right. And. That. Gives me this. Stream. Of benefits right. There's. Another system, that economists. Will sometimes use. To. Measure. What. Is the value, of something, in the future, and. That's willingness, to pay. That's, the W TP. Willingness. To pay and. That's contingent, valuation, right so, it might be something like. You. Know what would you be willing to pay for the Bengals sustain, Cincinnati, over the next ten years right. That's typically. A survey. Type question.

Economists. Will put out a survey like that get the money back and that gives them some kind of a contingent, valuation. Contingent, on the Bengals staying here for ten years what, are you willing. To pay. Obviously. There's some problems with that, sort of a measure because. There's. No stick to make the person peut you know the respondent, so. It's somewhat. Squishy. Or subjective. That willingness to pay, but. It at least gives you kind of a benchmark. To. Go from right. Let's. Actually know. What let's. But, we'll get four I was gonna take a minute workout. Present, value of future value, problem here in. Excel but to. Keep the, lecture at a reasonable, rate, we'll just keep, moving office, I'm, assuming, that you can plug the numbers into, that equation, here, and come. Out with. An. Answer. So. The. Winners curse this is another thing that's common. Amongst. Economists is, the common term, amongst. Economists well, referring, to events like, the Olympics, like, the Super Bowl or the all-star, game that, cities essentially, bid on hosting. So. The idea the winners curse is that there's. Somewhat. Of an auction, right. Cities. Are bidding to, host these, major events, the payoff, is relatively, uncertain. In, the future. The, winner who's the highest bidder, we. Would assume would, be that person that expects, the greatest payoff right. So. It, must be the city that is best able to exploit, the opportunity, because they're willing to put up the most money they're expecting. The greatest return compared. To other bidders so they're. Best suited to exploit, the, opportunity, of having the Olympics of the all-star game and that's why they're willing to put up more, than the, other bidders or. They. Might be the most over-optimistic. Right they might be overestimating, the, benefits, more, than the other bidders and that's, where the winners curse comes. In right. So. There's. This example Sochi, Russia, was famous for this, with. Their. Winter, Olympic bid. And what was at 2012. I think, when they hosted the Winter Olympics, so their initial budget. For. Hosting, those games was about 12 billion dollars. They. Went over budget by 39, billion. Dollars. Lots. Of speculation some. Of it substantiated about, corruption. That. Happened but. Essentially. The, cost of hosting those Olympics was 51, billion dollars. Compare. That to how much it cost, NASA's. Estimate of the cost of going to Mars about 2.5, billion. Seems. A little, out of whack there. So. That's the winners curse you win this mega that and then, all of a sudden you're on the hook to put it on and. You. Might have overestimated the benefits, and get in a little bit over your head in terms of spending, money right so. Let's, stop we've been talking a lot about these eras, of stadium, construction I focused, mostly on the most recent, era let's talk about two eras that happen, before this most recent one so, the first one around the turn of the century. 1900s. Meaning turn of the. 1800s. To the 1900s. Your. Book calls that the entrepreneurial, period. And by entrepreneurial. What, the authors mean is you. Had these baseball. Fan primarily, baseball, families. That. Got involved in baseball, when it was first becoming a spectator, sport of professional spectator. Sport, they, were building. Stadiums. That had the name that, were called, parks, or fields. Often. The baseball teams run into the local football team, earlier.

Versions Of the NFL, essentially. Usually. The facilities, bared the owners name, at. That time we of course have a couple. Stadiums. Still left from that era Wrigley. Field, noticed, the field their Fenway. Park right, also using the word Park both of those carrying, the. Original, owner's name. As well then. You had this period from about the mid 50s, to the 80s. Where. There was a lot of public financing, went, into stadiums to try, to use the stadiums. For. Urban development put. Stadiums, downtown. Build. Other things around the stadium. And. It. Would be like a showpiece, to get people to come back down downtown when a lot of people were at, that time moving. Out to the suburbs that. Remains. That, theme of using, a stadium for urban development continues. Into the next era the most recent era. But. Some. Of the public financing, has increasingly. Gotten called into question more recently, but. A lot of that public financing started during the Civic infrastructure. Period. And. Then, that, period also had the municipal, name which we saw here riverfront. Coliseum. Right a riverfront stadium that we had here. In Cincinnati Three, Rivers Stadium. At. Pittsburg carries kind of like a municipal, type name Veterans, Stadium in, Philadelphia, you know it's carries, sort of a municipal, or. You. Know honoring, somebody, in the community like veterans. Then. Today like I said some, of the public financing, has gotten called into question quite, a bit more and, so, it's more of a public-private, partnership a, lot. Of times to fund the private part owners. Use naming, rights on a few occasions naming, rights have been transferred, to the public. Side the city gets to sell the naming rights to offset, their cost that they're putting in of, course we've talked about, this before to the. Stadiums during this recent. Period have become sports specific, for the most part when. We're talking about the stadium's themselves, not necessarily, the arena's with the stadiums. So. Facility, construction costs, this. Is probably not, news. To you but it's. Gotten a lot more expensive to. Build football, and baseball stadiums, to the expectation. Of the NFL or MLB, compared, to what it used to be well. Past a billion dollars now and basketball. Arenas, are now starting to approach a billion. Dollars. Certainly. Over 600, million, Abbot's, field by comparison. Was. Considered, a pretty extravagant. Structure. When it was built in. 1913. Cost. $750,000. It. Was built, for the Brooklyn Dodgers we talked about how the Dodgers, moved, in in, the 50s. So, they played there for about, 40. Years. 44. Years something, like that but. $750,000. Even accounting for inflation, is, about. 17, million now. But. Our facilities, cost a billion dollars you can see sort of the, the. Expansion and a lot of that is creating, these luxury. Amenities. That. The, owners can. Capture. More dollars, from and not have to to, share with. Other teams in the league as much as they give the, actual, regular. Seats gate receipts. So. Here's a nice chart. Hopefully. You can kind, of pick. Out, some. Of the figures here. Your. Horses. Cincinnati, and Great American Ballpark. Gives, you the construction, cost of these stadiums through the years starting in 2000, with the Blue Jackets arena, up, the road from, us in Columbus all. The way through 2012. Marlins, Park. This. Also gives you some idea of how much was. What. Was the public expenditure, here so we get 86%. Approximately. For Great American Ballpark, we. Also have. Oh. Oh. Brad. Statement I thought. It was guess, we only get Great American Ballpark unless I miss it yeah. No. All. Right well we just. Get one of them um. And, also there is a set. Of slides, available. On blackboard, that has just, a couple slides specific, information to our ball park deals here in Cincinnati. Specifically. Hamilton, County which is the public financing, source was the county in that case that's. A separate set. Of set. Of slides you can get off a blackboard. So. During, this period this just gives you the averages, here's. The average cost. We've. Seen this cost skyrocket. Since 2004. Getting close to a billion dollars or over a billion for some of the recent, NFL stadiums, just announced, Cowboys. Stadium is over a billion dollars, obviously. Already in existence at. The stadium in Atlanta. That's being built is going to be over a billion dollars ought, to replace the Georgia Dome. So. During this most recent, rush.

And Say most recent now this stops, over. Ten years ago. But. During. This period. Here. In 1992, 2004. When. They started splitting up NFL, MLB stadiums. You. See. About. Two, thirds publicly. Financed. Versus. One-third. Private. Dollars during, this period this. Is probably. Well let's go back to the last slide this. Has probably, gone down a little bit since then look at these most recent numbers, so you've got the Nationals, Park which, was a hundred percent public but you see some lower numbers here right. 27:17, see. Some zeroes here, as. Well but you'll also see a couple higher, numbers as well. But. My guess. Is that this number, is going to start going, up in the future and, this, number, the public financing, is gonna probably, start, to decrease. Somewhat. So. What are the funding sources. On. The private side. The. League will, sometimes contribute, some money a lot. Of times that can be through a loan a really, low interest, loan, to the owners of the team. They. Can take out a bank loan just, like you would if you're gonna build a house or buy a new house, there, can be some equity. Investment. From. The standpoint of. Owning. The. Team right, so they could give. The construction. Company a little, bit of team, equity, that's relatively. Uncommon. But. Sometimes, the current owners are willing to put in some of their own equity into, the stadium if they have some, revenue. Associated. With, the stadium they're going to get out of it so usually, that equity investment goes with some sort of commitment. Like you. Can keep the concession, revenue or you, can keep the a. Certain. Portion of the, event revenue, outside, of your particular sport, so maybe concert, revenue or something like that the donors might be willing to chip in some of their own equity and. Then, facility revenue so facility. Revenues, could be like, we talked about before. PSLs. Right. Public. Seat licenses, or personal seat licenses, excuse, me were, there selling, to. Individuals, the right to buy tickets. And. They're using that initial, investment by, those fans. Essentially. It's a right. To buy their season ticket other using that money to fund the facility. Construction. Or the owners part of the facility construction, what about public funding sources well taxes. Of course that's what we've focused, on so far Lottery. Fund's so you see the example here the Ravens. Using. The lottery. Well. It's the Raven Stadium but Maryland, state, of Maryland. Issued. A special type, of lottery, of, which certain. Revenues went to fund the stadium. Bonds. So, cities will issue or, counties, will issue municipal. Bonds that have some benefits. Tax. Benefits, for the, bond purchasers. They. Can write, those bonds, off on their taxes, meaning, if I buy municipal. Bonds $100. Worth of municipal. Bonds I can deduct that hundred dollars from my taxable income and. Because that's allowable. It. Incentivizes me. To buy municipal. Bonds right to buy bonds from cities or from the county. Because. I know I can make some money on my taxes on the flipside it allows the county or the municipality, to. Issue, those bonds, at a lower interest, rate than. Say. A private, company that wants to issue bonds right, because they're not tax deductible so as an investor I'm, going to demand a higher interest rate from those bonds that are not tax deductible which.

Means The money is, a little bit cheaper for the city because, they can pay a little bit lower interest rate because, then they allow their, event the investors, in those bonds to deduct, the taxes. Cities. Might or counties might commit land that they own and say hey there. You go we'll give you the land if you build your stadium in this spot, grants. Rebates loans all, kind of the same. Type, of thing can be tax rebates. That. They use. To. Try and fund, the. Stadium, could be that. They get blown. From. Various, sources just, like a private company. Would although, they. Can usually get loans at lower rates. Because. They're a city and they have the. Ability to raise or lower taxes. To some degree to increase. Revenue to pay back any loans and, so they get a lower interest. Rate on those loans because, they're less risky, from the bank's perspective, user, fees so, it. Could be a tax on tickets, to events in the facility, attacks on parking, revenue. Those. Are different types of user, fees that, you might see, so. Let's look at a specific example here. Let's. Use the lions Ford Field. So. Ford, Field was one of those. Football. Stadiums that was right about at, what the average was at that point in terms of it being 300, million in 2002. The. Way that they financed, it so Wayne County, just like we had Hamilton County here funding, Paul. Brown Stadium Wayne, County, was the public. One. Of the two public. Entities. Contributed, money to this they. Issued bonds and then, they used an 80 million dollars in bonds and then they used a one percent hotel tax and a two percent rental car tax to try and pay off. The. Bonds right, after, the issue. And. The idea there is you're taxing people that are coming in from out of town right. People. Were using hotels, using, ranked rental. Cars, so. You're it's, a little bit less controversial. Because. You're not, conceivably. Taxing, people who actually live there you're taxing the tourists, that come in. Also. The Detroit downtown Authority contributed, forty, five million dollars Ford. Bought, the naming rights as you probably realized they paid. Forty. Million dollars for that. Over. 40 years that's probably a little bit low they got a good deal on that partially, because. Well. This, gets back to sort, of shifting money around the owner of the Lions is. The. Ford family. So. Ford. Cuts that deal. They don't pay quite, what probably, naming, rights market value is which means the Lions. Get. A little bit less. But. It also makes the Lions look less profitable than they actually are ford, keeps it a little bit more right Ford. Is in a business that they don't have to share revenues, with other teams or, they don't have to negotiate well, they do have to negotiate with their United. Auto Workers but, not. In the same way that NFL. Teams undergo shooting with the players union rights NFL teams have a little bit of an incentive. Not. To look like they're making a lot of money right. But. Anyway, that's. Hearkening, back to our. Discussion in previous chapters of how owners. Who, owned another, business entity besides their team sometimes, shift, money around a, little bit. But. The point being that they did use the. Lions use that money from Ford, to.

Finance, Some, of their portion, a Ford. Field and. Then, the rest of the money came, from an alone. Low-interest. Loan from the league itself. Allows to build their new stadium. Paying. For stadiums. So. There's. Two, good reasons that we've already talked about for. Arguing. That the public should finance sports. Stadiums. One. Is that teams. Are a public good right, my, pride. In place that I get pride, in the city that I get from Cincinnati. Being, a professional sports city does. Not exclude, you, from also, taking that pride my, identification. As, a Reds, or a Bengals fan doesn't exclude you from also, feeling that same sort of identification, with, your hometown, team, so. There's some argument. There the. Other one would be what we talked about with externalities. Right, the positive, externalities. Outweigh, the negative externalities. Therefore. The. Government should chip in to make sure that an appropriate quantity. Of this, particular product, is. Supplied, to the, city or the marketplace. Because. In a private situation a, private transaction situation. When there's positive, externalities. Usually, the, private transaction, provides less than the optimal. Quantity for. People, so. Markets, under provide goods with positive, externalities. Right we talked about that in Chapter six looked at a graph to. Show how to show, how that was true. So. Those would be the kind of the arguments for it another. Aspect, of that would be. Related. To that it's like the psychic, go, to the city or the branding, of the. City itself again. That's. Sort, of an externality, that's, kind of a combination these two things it's a public good, that we can take pride in it but it's also a positive externality, in, terms of it increasing. The, brand of the city itself right. That's an externality, because. The, city is sort of a third party to this transaction. Between the fans who are using the product, the team, itself that's. Producing the product. So. What. About. Taxation. There's. A three, different terms here that come up in the book one, is the Ramsey rule which. Is essentially. Saying that, the, most efficient. Taxes. When. It relates to sales tax is to tax something that there's high. In elasticity. Of demand before. So. The. Reason, for that as. You see listed there does minimize deadweight, loss but the reason that it minimizes deadweight. Loss is that. If you tax something with, high in, elasticity, of demand that. Increase, in price that the tax creates, doesn't. Influence the quantity, purchase. That much right, so, it. Creates, the, actual tax dollars. Being generated, and going to whatever, the taxes for whereas, if you tax something where there there, is elasticity. Of demand meaning, the, elasticity, is. The. Consumers, are very price sensitive they, will not, buy as much when, it gets taxed and the price goes up then. You put that tax on and there's a lot less quantity, sold, right.

You. Follow me there so, the. Ramsey rule is saying the, best things to tax or things where there's any last disappea of demand meaning, the price going up will not really affect the quantity that much versus. A very inefficient tax, where there's a lot of deadweight loss happens. When, tax, something that. There's lots of price sensitivity, to and the. Demand. Drops off right. Then, you don't get as much of the tax dollars right it's very inefficient and there's not as much of the quantity, produced, if you tax something. With. High. Elasticity. The. Other two things vertical, equity, in horizontal, equity you're. Probably already familiar with. Conceptually. A, vertically. Vertical. Attacks. With vertical, equity, is. Where. People. Who can pay for the tax are the ones that incur, most of the tax right so income tax is a vertical, equity tax right horizontal. Equity, is, where whoever benefits, from. It should, have to pay regardless of. Whether they can afford to pay or not pay so. Sales tax, is, sales. Tax on say groceries, is like, a horizontal, Akwa t tax right we all have to eat well, we all benefit, from getting the, food itself right. But. You're how, much you, have to pay in sales tax on groceries is the same as how. Much a very rich person has to pay on sales tax not that you're not rich some of you might be, but. Your income level doesn't, influence, your. Level of sales tax on groceries. Actually. Coming back here let me say one more thing on this so we. Talked about lotteries, and used fun teams lotteries, are also used to fund an education quite, frequently. Lotteries. Who. Do you think buys a lot of lottery tickets people who are rich for people who don't have money. That's. Right not a lot, of rich people buying, lottery tickets. Which. Means lottery. Tickets. Are what's, called in, some ways a regressive, tax instead. Of a progressive, tax a regressive, tax meaning, you're. Taxing, people who are, maybe. Have the least ability. To. Pay that particular tax, right. Versus. A progressive. Tax is, similar, to vertical equities where you're, taxing the people who can most afford to pay pay. Sales. Tax and tax burdens, this is just a graph. This. Is a we use for example a hotel tax right, so. Well. Let's look at this graph initially, right so without. A sales tax you've. Got some level of demand for hotel rooms you've, got a certain level of supply, of hotel rooms at different prices, right our supply curve we. Find that the quantity. Equilibrium. Quantity, is here. And. Here. But. Then, like. For instance we, saw in the example Ford, Field Detroit, implements, attacks on hotel rooms, let's.

Say That tax is $10 right that's. Going to shift our supply curve like we've seen before, over. To the left. That's. Going to mean that. Our. Equilibrium, changes. To. Here but, our. Price. Is now as, our price increased by $10. No. Here's, $10. Right our price is only, increased, by it looks like a fraction, of the $10 maybe five or six dollars made $5. Less. Than $10, the. Rest of the tax is paid by the hotel. Why. Would the hotel be willing to, incur. This tax well. They're. Hoping. That it's going to create more, demand. By. Having whatever, this tax is going to support so if it's going to support a new stadium downtown. That. The hotel is hoping, that the demand curve that this new stadium is going to shift the demand curve out to the right a little bit right, and that's going to help them. Sell more hotel, rooms than they used to so, even though they have to incur some of the tax. They're. Thinking that they're going to sell more quantity. We don't see that happen in this graph because we're. Not making the assumption, that the demand curve shifts it, may or may not shift. But. That assumption isn't made in. This particular example, so. This. Is getting to the Ramsey rule kind of the last part of this chapter. So. Let's, think about a product, here, that. Has. Relatively. Elastic, demand, right. And that's what we're seeing on this graph. Here okay, so. You see, that the demand curve, is. Not. By. Any means completely, horizontal, but there's certainly a horizontal. Type slope, to it here right. We can see at different, parts of the graph just. Looking at the demand curve here that as. Price. Increases. Say. From, F, to. A F. It. Was quantity. 0 was. Demanded, once, that price increases. To. A we. See right. Quantity, goes down. In this regard we've, got a sizable, or, decent, gap here right, with. That change in price. Now. The. Book uses, this. Is kind of a drastic example. But for any elastic demand something like dialysis, treatment, right for, failing kidneys. So. If. You need that treatment. Or. You're gonna die you. Are going to get that treatment no matter what the cost is right, so we see a very vertical. Demand. Curve here. So. As the, price changes. Say. From. Point. C or, whatever. To point E right. You, see very, very little, change in if. We. Move. Down you see very, very little change, in. Quantity. Right. Not. Much of a difference here even. Though there was this drastic. Rise. In price right. So. Let. Me get back to this for a second so the ID this is the idea of the Ramsey rule right that, you want to tax something, that. Is again. There's a obviously a moral, issue to this but in. General you would attack something with inelastic demand. Because. It doesn't change the quantity that much right. This. Is going to be our dead weight loss. Area. Here. Notice. How this is this dead weight loss area, is much bigger. When. You tax something with. More. Elastic. Demand. And. Here it is, in. A series, of kind. Of graphs right so, same, same idea here we've got to man we've got supply we've got some. Sort of equilibrium. Quantity. Before. The tax, we've. Got this consumer, surplus here, so people on the demand curve here are willing to pay more, but. They're getting it they're, getting the product, at the, Librium, price it's a consumer surplus right. I've. Got a producer surplus. Here right, they're willing to supply it at a much lower price in this part of the graph but they're getting this price so this is. Supplier. Or producer, surplus. Gain. To society, is the sum of the two all. Of these right some goes to producers some goes to consumer, all. Of those are. Each. Of those as part of our societies that's the game. So. What happens within a tax situation, well an attack situation right supply shifting, to the left we. Go from this equilibrium, point, to, this equilibrium, point. All. Of a sudden our. Consumer. Surplus is reduced a little bit here right the, price has risen, price. Was. Used. To be here, now. The price has gone up to, this. Point right, price, is risen quantity. Is fallen right here was our original equilibrium. Price. There's. Our new. Excuse. Me equilibrium, quantity is our new equilibrium quantity. Quantity. Is fallen, right, all. Right. Oops. Whoops with the wrong direction, there. We go okay. Also. We see the. Producer, surplus falls right, now, we've only got this. Portion, and. Producer. Surplus right. Because. This. Is the. Quantity. Again supply, right. This. Is the price but. This. Gap here right, is, getting paid in taxes, it's not going to the producer it's going to the. Government let's say, that's. Imposing, the tax. Indeed. This, is the tax revenue, right so tax. Revenues taken some of the consumer surplus is taken some of the. Producer. Surplus. So, it's lost by consumers it's lost by producers, it's gained by others in society assuming.

The Tax is used for, some reason, that's going to produce a societal, benefit. So. It's not necessarily, a net loss overall. Except. That. We. End up having whoops, whoops whoops we. End up having. This. Portion that becomes a, deadweight. Loss right. Because. Before. This tax was imposed the. Quantity, was, out here right, and the price was here. Now. The. Quantity is back here. So. We went back. In. Quantity, meaning. That these people on the demand curve did not buy, they. Will not buy with the tax right, too. Expensive for them up here they, would have bought at this. Equilibrium price, this becomes a deadweight loss and nobody realizes, the benefit, from those particular. Sales, it. Is that part then. Deadweight. Loss is a net loss to society. I, think. This is the last part here I, will. Zoom through here, syntaxes. We're familiar with that Cleveland, used that to raise, some of the public funding for. Cleveland. Stadium the, new Cleveland Stadium when, the Browns pull that's not new anymore but. So. The. Problem with syntaxes is that it can raise some money some tax revenue. But. Cigarettes. And alcohol tend, to be somewhat. Elastic. In terms of when price goes up people. Might, use. Less of it right so. When. You're sacked when you're taxing. Cigarettes. Or alcohol you. Might reduce consumption, which means less tax, dollars because, consumption. Is reduced there's. Some benefits, to that you might be discouraging, undesirable. Behavior, like smoking, that, can lead to health, problems but. Then you didn't get as much tax money so you kind. Of get one goal in discouraging, undesirable, behavior but you don't, get the other goal which is raising cash dollars. Tax. Incremental funding all right so a portion of Hamilton County's. Come. Into the, stadiums, that, we have for the Reds and bangles was tax incremental financing meaning. No. New taxes, so that portion, is not, applicable to Hamilton, County there was a new, sales tax but. There was also, an. Earmark on additional. Tax revenue, beyond. This. Certain point. In time right so, tax. Incremental financing is, where you say okay we've got 100 million dollars coming in in taxes, right now we're. Gonna pass this, tax incremental, financing which. Means that. On the first hundred million dollars of taxes next year there's. Nothing that goes to the stadium but on the next the incremental. The additional, taxes, next year over, our baseline so, say we, 110, million that, next 10 million, is. The incremental, part we're going to tax that at, ten percent say. Right. I, mean, ten percent of that additional, taxes, will commit to the stadium. They. Tried that in San Francisco in San Diego. The, problem is it's very. Fluctuates. A lot with the economy, by, how much tax revenue is raised so if. You pass something like that to try and pay for stadium and then the economy goes in the tank. You're, in big trouble because, you. Might not have any incremental, taxes your tax base might go down a little bit right then. You're not raising any money for the new stadium and you're on the hook to pay for typically. Its bonds, that the city or. County issues, you've, got to pay off those bonds when they come due so. You've got to get that money somewhere. Milwaukee. And Seattle, used to horizontal, what we would consider horizontal, equity they just taxed, the. Local. Retail. Businesses. Around the stadium that they thought would get a lot more business. Because. The stadium was being built so, they, remember. Horizontal, equity is taxing, the beneficiaries. Right. And. A. Ticket. Sales tax, right that. Goes toward building stadium that'd be another example of a horizontal equity. -. Debt. So. Just because the. City borrows, does not mean that they're not going to tax they're. Gonna have to pay back that debt right I've already mentioned that a couple times and, the, way that the city raises revenues is usually through taxes, so even though they might issue bonds are going to debt through some, type of a loan usually. They've gotta increase, taxes, at some point. To. Pay off that debt when, it becomes due but. I already talked about there is some advantage to municipal, bonds being tax deductible, to. The investors, that buy the municipal. Bonds which means that. Cities can pay less, and interest when. They issue those bonds and still get investors to buy them. That's. It all right so I know I went pretty quick through that there was a lot of information to digest, you can always of course we rewind go back, always. You can as you're watching this send me questions write down questions, bring. Them to class or.

Office Hours. As. Well. But. After. This is the midterm right, I have. Posted on blackboard or will post on blackboard, a short. Midterm review all that's going to be is me pulling together some of the key slides from, some of our past. Lectures. And chapters, to. Help refresh your memory it's not going to be everything that's going to be on the midterm exam. But. It will hopefully help, you refresh your memories you go back and think about what are the key points that I need to remember and, focus. On as. I do my study.

2019-01-02 05:54