African-American Business and Community Development in St. Louis, 1765 to the Present

- Good afternoon. On behalf of the Trulaske College of Business and our partners at MU Extension and Engagement, welcome to this, our seventh offering of the Trulaske Business Insider series. My name is Ajay Vinze, and I have the pleasure and privilege of serving as Dean of the Trulaske College of Business. Today's session is being moderated by Lathon Ferguson. Lathon is a member of Trulaske College of Business Advancement Group. The presentation and discussion today is certainly most timely and I'm thrilled to be here participating in it with you.

The focus today commemorates Black History Month, and I'm delighted that Dr. Miller W. Boyd, III is with us to discuss African-American business and community development in St. Louis from 1765 to the present day. So without further ado, let me turn it over to Lathon. Thank you so much for joining us.

- [Lathon] Thank you, Dean Vinze. Good afternoon, everyone. And thank you for joining. So I have the distinct honor and pleasure of introducing our speaker for this afternoon, Dr. Miller Boyd.

And so it's just so serendipitous, right? As we conclude Black History Month, thought it would be great to do it and to end the month with a topic that ties business and education into one another. And how once we leave this wonderful university, right? How it shows up in the world. So Dr. Miller Boyd, III is a native of St. Louis, Missouri. He received his bachelor's degree in sociology from Xavier University in Louisiana. From there, he went on to obtain his masters of African-American Studies at Boston University and then concluded his educational journey.

Although he is an eternal student, but he concluded his formal educational journey with a PhD in history from the University of Mississippi. He is currently an educator in the St. Louis, Missouri area for Whitfield High School College Preparatory. And he is the proud father of some wonderful children. His concentration and his research areas are 18th and 19th century African-American history, Civil War history, race identity and slavery in American Gulf coast, African-American 19th century Labor History and Atlantic World history. And so without further ado, I will turn it over to Dr. Miller Boyd, III.

Thank you. - Thank you for that wonderful introduction, Mr. Ferguson, if you could put those slides up and then we'll be ready to go. All right. Well, good afternoon, everyone.

Thank you for having me. The confines of African-American history have often been relegated to stories about a select cadre of Black luminaries whose names are invoked every February. The problem is that a myopic focus on Martin Luther King and Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman keeps us from learning about other dynamic figures whose stories serve as an instructor for the present generation recognizing and understanding and being familiar with African-American history is beneficial to you both professionally and personally. It helps you to understand the diversity of the American experience, and it provides opportunity for collaboration to make this state, this region and this country better.

Next slide please. So today I wanna talk to you a little bit about African American St. Louis. We'll talk about entrepreneurship, business, labor and community development. Now African-American history in Missouri stretches back about 300 years beginning when French explorer, Phillipe François Renault brought almost 500 enslaved Africans from San Domain. What is now present day Haiti, to work on the territories lead mines in 1720. Slavery is going to persist in the French territory when Auguste Chouteau founded the city of St. Louis in 1764.

People of African descent along with enslaved native Americans worked as forced laborers in a variety of capacities, agricultural laborers blacksmiths, cooks, and personal servants. Next slide, please. One more, I'm sorry. Guided by what was called the CODE NOIR, which we see here on the left were rules of French slavery provided some legal protections for enslaved people. And under French and later Spanish law, some enslaved people were able to receive their freedom through a legal mechanism known as Quenta zione This was a legal mechanism that allow for self purchase or allowed for family members, friends to purchase someone out of slavery. And during the French and Spanish colonial period in Missouri and in St. Louis,

there were a few people of African descent who were able to navigate life in the precarious space between slavery and freedom. One particular woman, Jeanette Fortchet was a former slave in Indiana, I'm sorry, in French, Illinois country, and came to St. Louis around 1765. She would be one of the city's first official landowners obtaining a plot from city founder, Pierre Laclède.

As part of a small free black community in St. Louis, she and her family are going to eke out a living in a variety of ways such as farming, hunting, running a laundry business, practicing folk medicine, and bowring free Black laborers. We know that both of her husbands were skilled laborers giving them more access to resources than other Black St. Louisianians at the time. We also know that this also gave them access to wealth.

We know this by virtue of an inventory of possessions what you see here on the right. That was created after the death of her second husband, Valentin in 1790. Her children inherited her possessions following her death in 1803. And one of her grand daughters Julie would marry a butcher and cattle dealer by the name of Antwan Lavidi who was one of the wealthiest African Americans in St. Louis before the Civil War. Jeanette and her family would be representative of a small free class of color, that could own business and determine their destinies to an extent. And although existing in a society that was race-based, their physical and even sometimes their social proximity to other races ensure that they interacted and did business with different types of people.

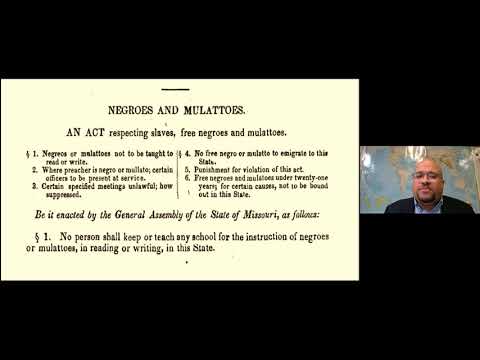

Next slide please. Entering into the 19th century, African Americans made nearly 20% of St. Louis' population, but yet after the United States purchased Louisiana territory in 1803, laws for People of Color became more repressive. It actually became illegal to teach Blacks and Mix Race People. More importantly, the guaranteed ability to buy oneself out of slavery, or to have someone else buy them out of slavery, a right that was guaranteed by the Spanish was removed. Next slide please.

Additionally, and maybe more importantly slavery became more vital to Missouri's economy after the creation of the cotton gin, that you see on the left, this led to a flood of people coming from places like Tennessee and North Carolina and Virginia trying to move their agricultural operations westward hoping to get rich by growing cotton. So as a result of the changes that happen in the United States and after they acquired the Louisiana territory, even the most enterprising free African-Americans had difficulty controlling their lives let alone achieving a measure of financial security. But while rampant, poverty and marginalization restricted the ability of most African-Americans to achieve a measure of financial stability in the 19th century, a small class of block elites emerged in St. Louis before the civil war. According to Sabrina and clay Morgan. Oh, go back to the other slide.

According to Cyprian clay Morgan, a descendant of of the wealthier Black families in St. Louis, African-Americans in the city controls several million dollars worth of real estate in 1858, a sizeable percentage of what he called the color of aristocracy, were barbers a lucrative profession in the 19th century that was almost exclusively the realm of Black men. Next slide, please.

One of the more noted black barbers in St. Louis, Robert J. Wilkinson owned an establishment of the prestigious planter's house hotel and was worth slightly more than $21,000 in 1858. If we adjust that for today's money that means he was worth about $600,000 in today's money. Other blacks like former enslave one Polozzi Rutgers made money through real estate speculation and other investments.

In 1860, her net worth exceeded a half a million dollar in today's dollars that's about 14 and a half billion dollars. Next slide, please. The marriage of Rutgers daughter, Antoinette to barber and landowner, James Thomas created one of the wealthiest Black families in America being worth at their height about $800,000 in 1870. And because of deflation, that was also equal to about $14 million in today's money nothing to sneeze up. What you see on the left, you might be able to read that but that was what we call his free Negro bound.

In order to be a free person in Missouri you had to have this insurance policy to ensure that if you've got to measure a trouble that somebody would be compensated for your mischief or what have you. He was a very important person in Missouri. And as you can see from the obituary on the right side he knew some very famous people including a former president of the United States, James K. Polk. Now, while these tales of Black success are fascinating they were not the norm. The condition of most African-Americans in St. Louis lagged behind because of oppressive racial policies and lack of investment in black communities.

All you had and surprising businessmen and women, poor access to capital made it hard to create lasting and sustainable businesses that anchored large communities. St. Louis would have a variety of free people of color that straddled every imaginable social position. We talked about the black elite, but St. Louis also contained a free Black middle and lower class that also made their living in any way they could.

in an urban area like St. Louis, you would have African-Americans who performed skilled labor served as butlers, worked on boats and ran their own establishments like salons. Others hire themselves out for odd jobs and the like. Their freedom of course was tempered by their race.

By the eve of the civil war. The black population in Missouri had jumped considerably. And although they constituted excuse me, 10% of the state's population in 1860, there were more people of African descent living in Missouri than ever before. Most of them being enslaved. Of the 114,931 black Missourians enumerated for the 1860 census, almost 97% were held in bondage. The remaining 3% of the population were free blacks, 3,572 of them in all.

And the vast majority of them lived in St. Louis. Now, the manner in which African-Americans both free and enslave responded to the civil war, had almost everything to do with financial and physical security. Or many narratives of the civil war focus on black enlistment and imply, or even directly state, that black men joined the union army to emancipate the entire race, or to affirm a nascent sense of patriotism. My research demonstrates that the opposite was more than likely true. Black men, both free and enslaved, like their white counterparts made decisions about enlistment based on their immediate needs, many of them being financial.

Only were definitely concerned about the status and welfare of enslaved people across the country, many who shared their same condition and slave men only enjoined the army only if it was advantageous to them, financially. Many families, many men whose families were literally starving during the civil war or in poor condition, did not have the luxury to think about collective emancipation or patriotic self-sacrifice. If enlistment provided them with what they needed freedom and a steady income, they joined the army.

If there were other options many chose to do other things like engage in free labor. - Dr.Boyd. - Yes please. - Dr. Boyd.

- Yes, sir. - I just want to ask real quick... So we have had a couple of questions that have come in about a couple of the topics that you have just briefly touched on. If you want me to give them to you now for you to answer or do you wanna do it at the end? - Let's do it at the end.

- Okay. - Let's do it at the end. Can we get to go to the next slide, please? During the civil, we see that a state and regional economy moving from an enslaved labor to a free labor model and a slavery class a number of farmers, businessmen needed to fill jobs left by those who had fled bondage.

Beginning in the spring of 1863, the union army began to match loyal employers with formerly enslaved people who were looking for job opportunities. The union army helped to drop contracts like the one we see here on the screen and oversaw the program to the extent that they could. This free labor system was successful to the point that it helped to alleviate the financial pressures of feeding and caring for black refugees, fleeing their masters, during the collapse of slavery in Missouri. But for some this labor system this free labor system was too successful. The proliferation of free jobs, free labor jobs throughout the Midwest made it very hard, especially in the summer of 1864 to recruit black men for the union army. Out of the estimated 20,000 able-bodied black men in Missouri during the war only about 8,400 actually served in federal regiments.

Next slide please. Well, the enslaved men were not the only segment of the population who were circumspect about military service in relations to the financial needs. If certain segments of the enslaved community viewed federal military service unfavorably because of financial concerns, the vast majority of free black men in Missouri rejected federal enlistment altogether.

As it had been with their enslaved counterparts free black man also viewed military service through the lenses of opportunity individual need and necessity. And although their race limited their employment prospects free black men, especially in St. Louis were often able to secure steady jobs in a variety fields during the civil war. Black man not only found jobs as simple laborers or farmhands, but also found employment in more specialized occupations, which paid more money than the army did.

Some own businesses like salon owner, Robert Smith, tobacco is W. Harrison and Shoemaker R. Hill. Blacks and service occupations like Charlton Tandy, a Porter and Will Brady a waiter, could earn enough money to provide for their families. Some African-Americans in fact, made considerable sums by working as riverboat pilots and barbers men like businessmen, Henry Clay Morgan owner of a popular downtown barber shop and bathing salon known as Clay Borgan bath dedicated to such luminaries as you list this us grant William to come to Sherman and others had enough discretionary income to pay a substitute to serve in this place. After the war department order the draft from Missouri in September of 1864. We have insight into the lives of free blacks and their financial concerns from military records which we see right here on the screen. Many of them did not sign up for federal service during the war, but beginning in February of 1865 those who had not enlisted in the army were mandated by mandated by law to register with the Missouri militia.

The vast majority of these men who enrolled at St. Louis were black men who were skilled laborers or business owners. And you might be able to see some of their occupations they're highlighted on the right. Free black men, especially in St. Louis could earn far more than the 10 to $13 paid to African-American soldiers during the war.

And as a result, interestingly enough by and large rejected military service. Next slide please. So because the federal army paid considerably less than some black skilled and unskilled laborers could earn them off, free Black men may have actually seen enlistment during the civil war as a financial burden. And we know this to be true by virtue of the more than 3000 black men who were forced to enroll several months before the civil war ended. We can also see these concerns about a soldiers pay and a letter from a black barber and a business owner to the head of union operations in Missouri.

You might not be able to read it this handwriting but I'll read it to you. It says, "I think that I'm sufficiently patriotic to go into the ranks, but a young family who were dependent on me for support could not live upon the pay that is paid to a private. If nothing could be heard I should like a recruiting commission." So this Barbara is saying, you know I will not be able to take care of my family if I'm paid like a private, if you'd like to make me an officer a recruiter and pay me a decent wage, I'll be fine to affirm my patriotism and go into the army. And he implied that if he didn't get the pay that he was looking for that he would stay working in his business.

I did try to search for a response letter and to see whether he was able to get that recruiting commission. I was not able to find a response letter and more than likely he was not granted his wish. Next slide please.

So the civil war change the landscape of Missouri and the entire nation. And during reconstruction, there was hope for a broader social and political and economic future for African-Americans. At that time, African-Americans had the ability to bank with very few institutions. One was the Freedman's Saving and Trust a financial institution established by the federal government starting in March of 1865.

The St. Louis Branch opened in 1868, but it shuttered its doors because of fiscal mismanagement at the national level and the economic downturn that resulted from the panic of 1873. The failure of this bank wiped out the savings of scores of African-Americans around the countries and established a feeling of distrust among African-Americans regarding doing business with banks, that extends to this day. Next slide, please. But at the beginning of the 20th century African-American prosperity, waxed and waned in St. Louis,

extreme poverty among African-Americans continued to play the region but you also had African-American success stories. One of the most notable is that of Annie Turnbo Pope Malone. Some of you may have heard of her. Malone was born in metropolis, Illinois, and came to St. Louis in 1902. She like others, was concerned with notions of beauty.

And as a result founded a haircare company that she called Poro. She invented a formula to help black women manage and grow their hair. And with a team of employees she sold her product door to door.

One of the people who would work and learn the business from any Malone would be Madam C.J. Walker. The woman who erroneously is recognized as the first black millionaire. But regarding Malone she was dogged and determined and Malone's product became a hit and made her very wealthy. Despite the fact that white banks had refused to finance her expansion she became a multimillionaire by 1920. Next slide please.

Malone's success allowed her to build her own manufacturing plant and stores. Additionally, invest some of her profits and to what she called poor rural college, a cosmetology school for African-American women. Next slide please. Poro college also became a prime meeting space for African-American social clubs and fraternal organizations like Alpha Phi Alpha who held its closing banquet at their 1922 convention.

Malone was a very important figure in black St. Louis. Malone gave her her time and her money to worthy causes one being what was called the color orphans home which was located in North St. Louis. This orphan's home has now been renamed, The Annie Malone children's home. Now the great depression and a contentious divorce. What reduced Annie Malone's net worth but her legacy is still seen in St. Louis

with an annual parade given in her honor. The Annie Malone parade, which usually is scheduled in May of every year is the second largest African-American parade in the country. Next slide, please. Aside from Annie Malone, there were other enterprising African-Americans that skillfully navigated Jim Crow St. Louis

in the early 20th century. African-American entrepreneurs invested in salons like we see here on the right, The Rosebud Bar and funeral homes, like the one we see with Harrison and McKoin here on the left. They also have other independent businesses focusing on things. Next slide, like barbershops, carpentry general contracting newspapers and others. These advertisements come from a defunct African-American newspaper called the St. Louis palladium.

And they were scores of ads that were issued and printed weekly. There were also other entrepreneurs who trIed to make their way in Jim Crow St. Louis. But since what banks did not normally lend to African-Americans Black businessmen had to create their own finance companies. And the 1915 African-American high school principal and community leader Frank L. Williams

founded the first African-American owned financial institution in the state of Missouri. It would be known as, the New Age Building and Loan Association. Next slide, please. Eight years later, a local black businessmen founded what was known as People's Finance Corporation, catering to a mostly or exclusively minority clientele, both of these institutions would help African-Americans buy their own homes and start their own businesses.

And while People's Finance Corp and The New Age Building and Loan Association were seen as a godsend to families and businesses. These small institutions did not have the resources to serve the entire African-American population in St. Louis And as such financial stability often alluded many in the black community. Next slide, please.

Aside from challenges, getting access to capital there were also other barriers to financial success. Restrictive real estate covenants. These are agreements made between a property owner and a buyer to not sell to a particular race or ethnic group. This became common place in St. Louis starting in 1917. After the city voted to enforce residential segregation by law, this effectively reduced housing options for African-Americans and made our city more racially divided. Redlining, that is the refusal to lend to people who live in a particular part of town because on paper they are considered a poor financial risk.

This also kept large swaths of the African-American community financially stagnant and impoverished. Next slide please. But in spite of segregation, two dynamic African-American communities emerged in St. Louis in the 20th century.

The Phil and mill Creek. Well, the Phil was the most celebrated of the two. Malone's Poros college, Homer G Phillips hospital and Sumner high school anchored this dynamic community. I've already mentioned Poros hospital but both Homer G Phillips which we see here and these images, and some of our high schools were transformative community institutions.

Homer G. Phillips was one of the few hospitals in the country to accept black doctors into residency programs. And as a result, according to historian John Wright nearly half of all black medical residents in the United States during the time it was open came to Homer G. Phillips to complete their medical training. Let's go ahead. Let's go to the next slide after that.

Thank you. Now, some were high school on the other hand was an incubator of black excellence and when it was founded in 1875, it became the first black high school West of the Mississippi river. Its faculty was nationally renowned and nationally recognized and consisted mostly of black intellectuals, who could not by virtue of their race, find employment at white colleges. Next slide. One of the best examples of this was the man who we see on the right, Dr. Charles Henry Turner.

Turner received a PhD in zoology from the university of Chicago. Graduated in Magna Cum Laude in 1907. And although he was a world renown animal behaviorist with 70 research papers to his credit. He was forced to teach high school students at Sumner. And he did so from 1908 to 1922.

But Sumner students benefited from being taught by people like Dr. Tom and other top notch faculty. And as a result Sumner is gonna produce a number of famous graduates. Next slide, please. Now time does not permit me to highlight every noted Sumner grad and you might recognize some of them here. But a few of them, we should acknowledge would be former Congressman Bill Clay, actor Robert Guillaume, tennis legend Arthur Ashe, comedian Dick Gregory, singers Chuck Berry and yes, even Tina Turner. Next slide, please.

Now the other community that I mentioned, Mill Creek had a history that was more working class. But no less important to the African-American community. First established in the 1760s Mill Creek was one of the first parcels of land doled out during the French colonial period.

And as St. Louis expanded so did the population of Mill Creek. As wealthier people moved away from the bustling industrial downtown after the First World War. African-Americans moved in, looking for decent housing. And by the 1950s, more than 20,000 people called Mill Creek home. while they was not as prestigious as The Ville, Mill Creek was a multifaceted community.

And according to Bruce Olson, by 1955 it contained a vibrant mix of more than 800 African-American businesses, churches and other associations. Next slide, please. Now, while you had a Sumner high school in The Ville, there was a Vashon high school in Mill Creek.

And Vashon will have a long list of famous graduates including Congresswoman Maxine waters, boxing champs Michael and Leon Spinks, jazz great Clark Terry and one of the most important soul singers in musical history. And I believe he was just honored by the GRAMMYs with a posthumous award. And that is Donnie Hathaway who you see at the bottom in the center.

Now, the decline of The Ville has been connected to desegregation and suburbanization in St. Louis. But Mill Creek on the other hand has a completely different story. Next slide, please. Mill Creek was the victim of an urban renewal plan that demolished approximately 5,600 buildings in clear close to 500 acres of real estate in the area just East of Midtown, beginning at 1959.

This was a severe hit to the African-American community both socially and financially. More than 20,000 people had to find a new place to live. And countless African-American businesses had to relocate or close. And so these are some of the actual notices of the businesses that had to relocate to other areas in St. Louis, just to stay open. Next slide, please.

Now going to the 1960s. The tensions of the civil rights era led to protest but it also led to opportunity. In 1963, after Jefferson Bank and Trust refused to hire African-Americans for anything other than custodial positions. Protestors marched and picketed at the bank for approximately seven months. Jefferson Bank is going to finally relent and hire four black clerks in 1964, but others were not satisfied.

And they believe that a better banking solution was needed for the African-American community in St. Louis. Next slide please. Oh, actually conceived several years before the Jefferson Bank protest, George Montgomery and a coterie of black lawyers, doctors and businessmen established what was called Gateway Bank in 1965.

Next slide. To cater to one of the most unbanked black communities in the United States. And from 1965, until 2009 Gateway would be a pillar of North St. Louis, a predominantly black area of the city. But despite the opportunities offered by Gateway Bank, African-American entrepreneurs still struggled to find a level playing field in relation to obtaining capital to start businesses in St. Louis.

Throughout the 1960s, the 1970s, 1980s and the 1990s African-Americans were routinely denied loans or were only offered loans at higher interest rates compared to their white counterparts. Barriers to financial stability stifled black businesses and made it hard for many of them to thrive, amidst increasing competition, from larger companies attempting to make inroads in the black community. Nonetheless, several African-American owned businesses flourished in the St. Louis region defying the odds. Next slide, please. After retiring from the NFL in 1975, former middle linebacker for the St. Louis Cardinals football team,

Jamie Rivers purchases first McDonald's franchise. Eventually he's going to own and operate four very profitable franchise restaurants. And over the course of four decades in the business he would employ several thousand St. Louisianians.

Next slide, please. Other black business leaders came to prominence during this time as well. In 1980 oral surgeon, Dr. Donald Suggs and two other partners became majority shareholders in the St. Louis American newspaper. This historic newspaper had been in operation since 1928 but at the time that Suggs and his partners had purchased a stake in the paper, its best days, many thought, were behind them.

Suggs is going to revamp the newspaper and its business model. And by 1984, he'd become the sole owner and publisher of the St. Louis American. Currently today Suggs has grown the paper to be the largest weekly paper in the state of Missouri. The St. Louis American has won numerous journalistic awards

and it's considered one of the best African-American newspapers in the United States. Next slide, please. Another African-American dentist, Dr. Benjamin Davis,

would also leave his Mark on St. Louis history. But not by not only purchasing the first African-American owned McDonald's in East St. Louis, but by opening another McDonald's on the St. Louis side of the river. In the early 1980s Davis opened a McDonald's on the riverfront. Some of us might remember this. Affectionately known as the McDonald's boat.

It would be a favorite summer destination for St. Louisianians old and young for more than two decades. And I was included in that number. Next slide.

Also in the early 1980s, husband and wife duo Reuben "Andy" Anderson and Katherine Anderson founded Andy's seasoning. Initially this was a home-based business but Andy's quickly took off. With products being placed in stores throughout the region. By 1988, they had outgrown their second location and moved into a 13,500 square foot facility on Chouteau Avenue, in the South side of St. Louis. Following the death of Reuben in 1996, who had run the day-to-day operations, Katherine took over and according to Andy seasonings more than doubled the size of the facility and quadrupled their profits, in a very short period of time. Today's our Andy's is known nationally as one of the most important food service companies in the region.

Next slide, please. Into the 1990s other African-American entrepreneurs would see even greater success. Colonel Jimmy Williams, another McDonald's success story, received his first job at the age of 16. Working at the McDonald's ironically owned by Dr. Benjamin Davis. Williams, who is originally from East St. Louis spent nearly a decade as a pilot in the Air Force.

And after acquiring first McDonald's in the late 1990s when he retired from active duty, Williams expanded his Estel Foods Company to include 18 restaurants. Williams currently employs 1300 people and has an annual revenue that is in the tens of millions of dollars. Next slide please.

But no discussion, about black success in St. Louis is complete without mentioning this man here, Dave Steward. After borrowing about $300 from a local bank in his hometown of Clinton Missouri Steward hitchhiked to St. Louis in 1973 to begin a job in sales.

And after a career with the Missouri Pacific Railroad, he founded a company known as world Wide Technology. In 1990. The business solutions company was started off with a handful of employees and he modest revenue has become one of the titans of business in the Midwest. This privately held company is now the most profitable African-American owned business in the United States.

Last year, World Wide Technology brought in $11.9 billion in revenue. Next slide please. But despite a record of success. Black entrepreneurs in 2021 still encounter obstacles to starting businesses in St. Louis. Despite solid business plans and a track record of running profitable ventures, African-American business people still note how challenging it can be to secure loans to start or expand their businesses. In a recent interview that I conducted with Darryl Jones who we see here of D&D Concessions.

He noted that getting his business off the ground was quite challenging. Despite obtaining a loan for several million dollars and properly repaying it, he had difficulty getting additional funding. With this he decided to move away from large financial institutions and Jones decided to work with local community banks who cater to his needs and establish a relationship that has continued with him to this very day. Currently D&D Concessions has a stake in 80% of the restaurants and food stands at St. Louis Lambert airport

and their portfolio is growing. Next slide, please. A similar sentiment in regards to the difficulties of establishing a business was recently echoed by Jason Wilson, the owner of Northwest Coffee and a member of the Clayton school board in St. Louis. Wilson sought to acquire a coffee roasting company in 2012. But despite his Washington University MBA and a history of entrepreneurship, he could not obtain a business loan. His business had to be privately funded with help from friends, family members and investors.

In a recent conversation that I had with Wilson. He noted that large banks have almost completely ignored what he likes to call "the urban domestic emerging market." And his conversation with me he said this, he said, "they need to get on board." And I will tell you, Mr. Wilson is doing quite well.

His coffee as some of the best if you ever visit St. Louis, please stop at Northwest Coffee Company. Although Wilson and others had to often trudge a rocky path to success.

African-American men and women in St. Louis and nationwide are determined to build upon the past to make an even brighter future for themselves and their families. It's going to be the black luminaries, both known and unknown who lead part of a diverse coalition of forward looking people who will help St. Louis reclaim its former glory. With the city, being at a crossroads where will you stand Mizzou business students, where will you stand? Will you recognize the opportunities to partner with people who will be part of the Vanguard for better and more prosperous St. Louis? Or will you lose out to those who can clearly see the writing on the wall? In many ways, past is definitely prologue.

And while the past reiterance cannot determine future gains, I would hedge my bets that there are many more Polozzi Rutgers, James Thomas's, Annie Malone's Dave Stuart's and Jason Wilson's right here in St. Louis and throughout Missouri. And they're looking to possibly do business with you. Thank you so much for your time. - Dr. Boyd.

So since we're not in person, I won't do my sound effects for a round of applause but I would just say, you know, on behalf of Trulaske college of business, we thank you for your time time today and for your presentation. Now, I know we have some time left. I wanna get to. We've had some very thoughtful questions come into the Q and A, that I wanna get to.

A couple of from, I want to say a couple of staff and faculty but the majority of them are from students. So let me get going right now. And I'll blend the first two kind of into, first two questions into one. So the first question says Cotton was not a dominant crop here in Missouri, were the Easterns successful in establishing themselves with slavery in Missouri.

- Well, Missouri is not going to have the type of success in terms of large scale plantations that you would find further South. Cotton is not going to be the big crop, I hope is. And still, that is still going to entice people to come from areas where probably the best parcels of land had already been taken or were probably too expensive for them purchase.

So no, St. Louis and the entire state of Missouri dependent upon slavery. In St. Louis, it was an urban version of slavery. So people were not just working in agriculture. But in the Seven-County region known as Little Dixie along the Missouri river, slavery was the foundation of the economy.

- Perfect. Thank you. IN the next one I'm going to, again I'm taking a little bit of an assumption.

But part of your presentation in the earlier years. The next question is, where were the sections of African-Americans inhabited in St. Louis? The predominants. - Where was sections where are, or are we talking about after residential segregation is enforced? - It didn't say. It just said, what were the sections? And I know you mentioned The ville and you know, those areas. - So The Ville is in, what we consider North St. Louis.

Mill Creek, if anybody's familiar with St. Louis, it is around Midtown. If you knew where the St Louis university basketball arena is, where Harris-Stowe is, that area was Mill Creek. It is now filled with things like Wells Fargo, other businesses and I believe the soccer stadium. The new soccer stadium was gonna be built in that area as well.

- Perfect. Next one comes from one of our students. I believe this is a student and the question is more personal for you. It says, have you ever faced discrimination when entering the workplace? If so, how did you overcome it and not let it bother you? - Wow. You're gonna get into

some kind of existentialism discussion, a very personal. - We got some Scholars Dr. Boyd. - I applaud them. I have been fortunate for those experiences to be very rare. I can give you one example, I was a financial advisor before I went back to school and I had inherited an account.

Then I went out on a home visit and you know I'm talking like I naturally talk on the phone, but when I got there the person opened the door and looked me in and slammed the door in my face and said, we don't want anything, please don't send us anything. And I was not gonna knock again because I didn't want something else to happen, but I went back to my car and I said, this is Miller Boyd. I was supposed to be meeting with you and your husband at six o'clock. I was the man at your door. And she profusely apologized but that kind of stung, but, you know, I persist, I try to be the best person that I can.

I try to lift up all people who I work with. And I have zero tolerance for racism, sexism, bigotry, homophobia, whatever. And I try to inspire that type of character and my students and those who I work with because we are all we're all Americans, we're all people, all human beings.

- Great. So the next one is who would you consider to be the greatest hero for black communist in Missouri? - Wow. - And I know this is more of your opinion, right? With that question. - You know, I'm not one of those people who subscribes to the idea that there's like this one Black leader that is sorta like Martin Luther King leading people to the promised land. I think there are a number of different people in different segments of the community.

They still, whether is one financially Jimmy Williams. When we think about politics a person like Tishaura Jones, treasure of St. Louis, in education or Rinaldo Anderson at her store. But there are many people, people known and unknown who are role models and leaders, on the macro and micro level and who make a difference every day.

- So next question. What was the panic of 1874 and why was there panic? - It was a panic of 1873. It was a financial crisis. It was a market crash.

And it's been a while since I've taught that period of of American history, that reconstruction era, I'm wanting to think it had something to do with the railroad, but I can not remember. I'm a little rusty when it comes to that financial crisis. I can tell you more about the financial crisis that resulted from Andrew Jackson, basically defunding the second bank of the United States, which led to a financial crisis during Martin van Buren his administration. Which should have been blamed on Andrew Jackson and not his his vice-president and his successor. - Gotcha. Question, was there a lot of segregation in St. Louis

after the civil war and beyond? - Yes, oh definitely. St. Louis has a really fascinating history when it comes to African-American history and race relations. St. Louis is definitely considered a Midwestern city but the state in many respects is considered sometimes the upper South.

We were one of force slave States during the civil war that never seeded were called border States. And by virtue of that, slavery will remain legal until the state constituted convention outlawed it in January of 1865. The emancipation proclamation did not apply.

So you had these areas, these urban areas like St. Louis, where they were fine with getting rid of slavery but those urban areas, I'm sorry those suburban areas, I'm sorry, rural areas like Little Dixie, held on to slavery as much as they could. And even after the civil war, there were many instances of African-Americans being targeted for reprisal. I gave a presentation recently where I discussed how there were these Confederate, these we call them bush rockers but these gorillas who after slavery was outlawed. And even after Lee had surrendered to grant in April of 1865, they were still trying to force African-Americans back into slavery.

And really by 1863, late 1863 the institution of slavery had collapsed around the state but they put a flyer on a local store saying that if blacks did not go back to their old masters and work as they had previously done, they will start killing people. And about 10 days later, they did. And those type of lynchings reprisals continued throughout reconstruction.

I think if I remember correctly outside of Southern States we probably had the largest numbers of racial lynchings in the country. - So I mean, questions are still pouring in, and again I know we got eight minutes to sit here. I'ma skip around a little bit and ask a couple more I'm trying some are really direct yes or no. So I'll ask this real quick. Are the buildings like the hospital and the high school still around? - Okay. Homer G. Phillips.

The building is still around, but the building... The hospital closed in the early 1980s under Mayor Vince Schoemehl. Now Sumner I should have, I'm sorry, Sumner, I should have mentioned, like I said it's the oldest high school, Black high school West of the Mississippi, the local school board because there are so few people attending St. Louis public schools. There are talks of shutting Sumner down. And a lot of people who were concerned with the history of preserving that history, have spoken up and they really would like to see Sumner remain open, but it's going to be very hard with the numbers pouring out of St. Louis public schools

into other districts and then to charter schools. - So here, I'm going to give you three questions again and then I'll let you pick which one, right? Because they're, very, (indistinct chat) (laughing) Okay, so this one is, I wanna say it's important because it brings kind of forward what you presented on especially from business standpoint. So this one says, can you tell us anything about the Delmar Divide, that's a whole nother presentation, but, so I'ma stick a pin in that.

And then another student says books by A.G Gaston and David Steward describes how to be financially successful. Our high is assigning these books and teaching students how to achieve similar success.

- Wow, someone brought A.G Gaston founder of, gosh. What insurance company? Wasn't Atlanta mutual, gosh. A.G Gaston was a big, big businessman in Alabama. And gosh, I can't think of the name of the insurance company.

I don't think entrepreneurship is being taught in many schools, Black or White. I think that it is important for students of all races all cultures to be instructed and financial literacy. I think that there needs to be some innovation when it comes to curriculum. I know here at Whitfield we do have an economics course but that is the senior elective, but I think it would be very helpful for students. You know, I think lately and you can probably remember us growing up.

We had home economics class and people have moved away from that and we had shop class. And I think those practical things, those practical classes I think are really important because, there are some adults who don't know how to balance a checkbook, if they ever use a checkbook, but don't know how to do taxes don't know the basics of saving. They either have to learn on their own or learn the hard way and hopefully you have to try and, you know try to get themselves out of a financial hole that they might put themselves in through credit card debt and other things. So, yes, it should be taught. I wish more people read people like A.G Gaston and David steward, Booker T. Washington, and many others.

But I think it's also incumbent upon parents and mentors to also suggest those books for students. - Okay. Two more questions and then...

And hopefully this one just straight forward can you identify the oldest family or corporately headed African-American business in St. Louis? - Okay, so the one that is, I think it was celebrated for 70 years of being in business. I believe it was call your motors if I'm correct. One that has been held by the same family. I believe that's called your motors which is on the North side.

In terms of other businesses that have remained in the same family I can't think of anything off the top of my head, but I assume that there are some. - Okay. And we'll make this the last question.

So the question says, could you expand on what led to the demise of The Ville? - So, when residential segregation was put in place people were forced to live in just two areas of St. Louis, and that did not give them the luxury of the type of homes that they wanted to build or if they wanted, a larger sprawling property. And there were some parts of The Ville before it's declined that were impoverished. And I think that people benefited from being in their own kind of ethnic enclaves but also people wanted to have choice. And what happens is that when areas by select Spanish Lake and other places start opening up for African-Americans people try to, especially when you know, it starts to go into a financial decline.

People are trying to leave and try to keep their family safe. They're trying to find good schools and people start to leave and they start to go to other places and people are scattered. And that of course is going to take capital and investment out of that community and, you know send it into a place of disrepair.

And despite the history of The Ville, The Ville's best days are long behind him. It would be nice to see some of those community institutions, reestablished and that history preserved. But in many ways it's a memory and sad memory.

It's sad that it is just a memory because it was a wonderful place. - Thank you. Go ahead, Well, thank you, Dr. Boyd, a student came in and said how can they find your research? So the last question is, have you done any research on African-American entrepreneurship in the KC area, e.g. Henry Perry, The Brian's, The Gates, e.t. cetera. - No, I have not.

I am familiar with it but that is not within the field of my expertise. I'm actually a civil war historian. And my focus is on civil war Missouri and Kansas city during the civil war is kind of a smaller area, being from St. Louis

and being asked to do research on black St. Louis and civil war St. Louis has gotten me more into the St Louis aspect best of history, but there is a great history and Kansas city one that I would love to be more familiar with.

- Well, Dr. Boyd again, I want to just take a moment and thank you for your time. Thank you for sharing this information with us any parting words or again, if you wanna, where can they find your research? And again, maybe hopefully we can have you back and do a second part in having you cover the Delmar Divide. - Oh, no, I'd have to do some more research about that. There are, I've got several YouTube videos. One was at Mizzou and 2016 where I spoke on my dissertation research about African-American life and African-American military service, free labor and education and Civil War in Missouri.

There is another recent, I did a talk last month for the African-American experience in Missouri, during reconstruction, that's on the Missouri historical society's website. There were a few articles out there that I've written. I think the most recent one that might be accessible is from the Missouri historical review from October of 2016. It is my hope that in the future hopefully the Summer I'll start working on my book based on my dissertation research. But, you know there are probably other things that are gonna come up and but hopefully I'll get that book started and hopefully done shortly.

- Well, we are one minute over. So again, Dr. Boyd again, thank you. Thank you for answering my call whenever I call thank you for your time. And we greatly appreciate your time.

This point this Friday. - And I say Mizzou is very fortunate to have you. We do miss you here in St. Louis,

but I know you're doing great things and there are more great things to come. - Thank you, thank you. With that, we are done. We have concluded the Trulaske Business Insider Series for February African-American Business and Community Development in St. Louis 1765 to the present.

So thank everybody for tuning in. We hope to see you at our next Insider Series and have a great weekend every one.

2021-03-10 10:29