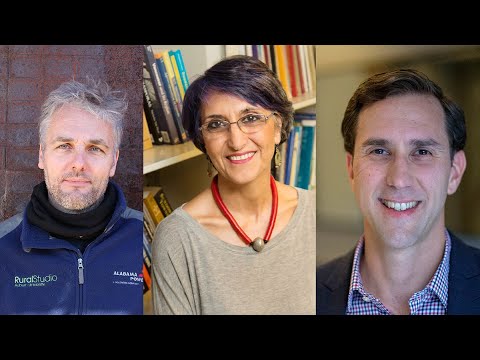

Small Town Urbanism in the 21st Century: Andrew Freear, Faranak Miraftab, and Todd Okolichany

Welcome, everyone. My name is Diane Davis. I'm a Professor of Regional Planning and Urbanism, and along with my colleague Eve Blau who's here today, we both co-chair the Events Committee in the Department of Urban Planning and Design here at Harvard's Graduate School of Design. We're thrilled to have you here for, what we conceive of as an inaugural event, in a longer series we hope to pursue over the next academic year, focused on what we are calling small town urbanism. Before giving a little background on what we are trying to accomplish with today's forum.

And I'd like to make an announcement about a few future events that will be of interest to you, I'm sure. Tomorrow at 7:30 PM the Black school and Brian C Lee JR. Will come together for a conversation about Black radical pedagogical experiments, both past and present.

Also on Wednesday, April 7th at 12:00 PM, that's 12 noon, architectural historian Rebecca Choi will give a lecture exploring the history of air rights through the lens of a specific case from the 1960s involving a developer, the residents of Harlem, and the Museum of Modern Art. All of these lectures will happen on Zoom, and so they will require registration. But more information is available about them on the Harvard GSD website.

And now a little bit more about today's event before I explain the content. Let me just say something about the event itself, the lecture series. It is supported by the 50th anniversary of the Urban Design Lectureship Fund.

And that fund was established in November 2020 to commemorate the founding of the first Urban Design program in North America, founded in 1960 here at the GSD. The lectureship was created by alumni and friends of the program to honor its important legacy. And the lead donors in that fund include Alex Krieger, our former colleague Jay Chatterjee, Leland Cott, and Moesha Safety. This spring, the fund was renamed to honor Professor Jaqueline Tyrwhitt who served as associate professor of the GSD between 1955 and 1969. And Professor Tyrwhitt worked to establish and fortify the urban design program during its founding years and committed much of her energies to shared discourse.

And so beginning in fall 2021, the Jacqueline Tyrwhitt urban design lecture will be delivered each year by visionary urban planner, designer, scholar, or leader. So without further ado, let me say a little something more about why we selected small town urbanism as a theme. We have been inspired, faculty and students of the GSD by several trends and developments in recent months and years that have produced a reckoning within their urban planning and design fields. Perhaps the most recent wake up call was the global pandemic, the recent global pandemic which in some parts of the country has accelerated an exodus from big cosmopolitan areas to more pastoral environments as people wait out the restrictions related to quarantine, school closings, and working from home.

But it is also true that even before the pandemic hit, such factors as climate change, the ease of telecommuting, and accelerating land costs in large cities have already begun to shift the population balance. Recent studies by labor economists have shown that greater access to job opportunities is no longer guaranteed in large cities, that itself stemming from the migratory flows of earlier decades. So if indeed the pandemic is going to transform the real estate market in cities, particularly for offices and firms, but also with respect to residential preferences, as some observers suggest, then we as design and planning professionals must be prepared to examine what this might mean for smaller cities and towns. Will they be growing and transforming as a result of population resettlement? And if so, how will we produce sufficient knowledge as professional planners, designers, and architects to-- not only professional knowledge but the appropriate tools, skill sets, and paradigms to respond to these shifts.

That's where we're going to be starting our conversation today. Now, in turning our attention to urbanism small scales, smaller scales, we not only have an opportunity to be self-reflective and critical about the ways that planning and design professionals have thought about best practices and to ask ourselves, what we have been teaching and modeling, whether that derives from a preoccupation with larger cities, which themselves have their own demographic, fiscal, social, and political character. We also have the occasion to question or at least rethink our assumptions about what smaller town life entails, and whether planning and design challenges are really that different in those settings. Are smaller towns actually less cosmopolitan or diverse than large cities? Are political and social attitudes different in market ways? Are these small towns likely to share the fundamental problems of housing in access, poverty, disinvestment, and lack of public or private resources necessary to transform the built environment in order to address climate change, poverty, inequality, and so on? So these are the questions we are asking about small towns and even whether they might be better positioned to thrive in upcoming years, given the environmental and labor force challenges that face large cities.

So these are some of the questions that our speakers will talk about today, we are confident. Before I turn it over to my colleague Eve Blau to say a little more about our three speakers today and why we invited them to kick off the event, let me just say that as we pursue this theme starting again next fall, we hope to address it from a multiplicity of entry points. We won't only be looking at the US, we will want to think comparatively as well as historically. For example, we hope to dive into a better understanding of the study of Utopian communities from the 60s here and abroad, consider both social and design experiments, some of which have perfected the back to the land, food security, or circular economy aims that are emerging today.

Likewise, we might want to think about small towns in larger regional settings that have been purposefully sustained as a part of national's territorial strategy as is more common in the European context. Those are just some examples of what will be pursuing next year. But no matter our focus, we hope to address small town urbanism armed with the theories and paradigms that have long preoccupied us at the GSD ranging for modernism to critical urban theory, so stay tuned for more on that series next year. In the meantime, please feel free to reach out to me and Eve if you have suggestions about related topics you'd like to call to our attention. But speaking of Eve, I'm going to turn it over to Eve now to take it away and add a few more words and make some more introductions.

Hello, I'm Eve Blau. Thank you very much Diane, I'm Eve Blau, I'm a professor of the history and theory of urban form and design at the GSD. And my main task is to introduce our panelists and our speakers, but I'd like to add just a couple of words to Diane's introduction about the larger program and project of which this panel is the inaugural event. We see this project itself as what I would call a project of scaling in the active sense of exploring relationships from multiple vantage points. And that by turning our attention to urbanism at smaller scales, we are foregrounding, sorry, we are foregrounding both the relativity of scale and also the specificity of place, as well as the relationships that scaling reveals between those places and the larger environments, regions, and networks in which they are embedded, including the ties that bind them to communities and to economies far removed from them.

So in this project we are also implicitly suggesting, or not implicitly but explicitly suggesting that small town urbanism is a critical framework that provides an important vantage point from which to understand the complexities of globalization including as Faranak Miraftab, who is one of our speakers notes in her book, Global Heartland, how as she puts it, the global inseparably nestles in the social and economic fabric of the local. So in this first event, in the series, we highlight difference among the sites of what we're calling small town urbanism in the 21st century, and among the professional and professional roles and engagements of our panelists in those communities. So it is now my pleasure to introduce our three speakers and panelists. Each of them brings a unique perspective to the idea of small town urbanism and each of them is also deeply engaged professionally in the places and communities in which they will speak to us today, engaged as an urban planner, as a scholar and theorist of planning, and as an architect and educator.

So our first speaker is Todd Okolichany. Todd is the director of planning and urban design for the city of Asheville in North Carolina. As planning director, he's responsible for leading sustainable growth, for promoting equitable development, and for shaping the built environment. In that role, Todd has led the implementation of key projects in Asheville that have addressed long-standing inequities in the community. These include a program of reparations for Black residents passed by the city council of Asheville in July 2020 to provide funding geared towards increasing home ownership, as well as business and career opportunities.

Todd will talk about this and other projects currently underway in Asheville. Before moving to Asheville in 2015, Todd oversaw the city of Fort Lauderdale's long-range planning program. Before that he practiced in New York City, where he also received a master of science degree in planning from Pratt Institute. Our second speaker, Faranak Miraftab is Professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where she also has joint appointments in women and gender studies, and geography. Her feminist transnational urban scholarship focuses on urbanization, citizenship, and insurgent practices of marginalized people based on class, race, and gender in many areas of the world, including the United States, Middle East, Southern Africa, and Latin America.

Today she will talk about the Midwestern town of Beardstown, Illinois, which is the focus of her most recent book, which I mentioned before Global Heartland, displaced labor, transnational lives, and local placemaking. This is a work which has received numerous awards, including the American Sociological Association's Global and Transnational Sociology Award and The Association of Collegiate Schools of Plannings Davidoff Book Award. That groundbreaking study in which she examines the lived experience of transnational immigrants from Mexico and West Africa, working in Beardstown's meatpacking plants, sheds important new light on the interscalar global, local dynamics that are reshaping small industrial towns in the United States and she will share those insights with us today.

Our third panelist is Andrew Freear. Andrew is the director of rural studio and is the Wiatt professor in the School of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape of Auburn University. For over two decades, he has lived in rural Newbern, a town with a population of 187 where he runs rural studio, which is a program that questions both the conventional education and role of architects. Under his direction, rural studio, which was founded by Samuel Mockbee in the early 1990s has expanded the breadth and scope of its work to address community need. Projects have become multi-year, multi-phase efforts across five counties.

His students have designed and built more than 200 community buildings, homes, and parks in their under-resourced community. Andrew Freear is a teacher, builder, advocate, and liaison between local authorities, community partners, and students. His work has been published extensively and he has received numerous awards, including the Architecture Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and most recently, the 2020 president's medal from the Architectural League of New York, which is the league's highest honor. And in addition, Andrew was a LOEB fellow at the GSD in 2018, and it's a great pleasure to have you back, at least virtually at the GSD.

Indeed, it's a great pleasure to welcome all of our speakers to today's panel, and I will now pass the mic so to speak to Todd, our first speaker. Thank you Eve. My camera froze for a second.

Thank you. I appreciate the opportunity to speak with you all today and I can't wait to visit Boston in Massachusetts in the near future. I hope everyone is doing well in this call. As Eve mentioned, today I'm going to be discussing the history of the city of Asheville and how the city has grown over the last 100 years and what we're doing now to try to tackle some of the impacts we're facing from rising housing costs, to overtourism, which is somewhat unique to the city of Asheville. In case you're not familiar with where Asheville is located, we're a city in Western North Carolina located about two hours away from the city of Charlotte and roughly three hours away from the city of Atlanta.

The city actually sits on top of traditional territory of the Eastern Band of Cherokee. And when folks visit the city, they're most familiar with places such as the Biltmore estate which is the largest private residence in the United States, the Blue Ridge Parkway which is the country's most visited national park and runs about 470 miles between North Carolina and Virginia, the Blue Ridge and Great Smoky Mountains and Downtown Asheville, which is home to-- really boast a lot of different varieties of architecture from art deco styles, neoclassical, classical, and other types of architecture that people come to visit when they come here. Although the population in Asheville is about 94,000 people, we really experience a lot of visitations. We experienced before COVID over 11 million visitors per year, which is a tremendous amount of visitors for a city of Asheville's size. They come here for some of the reasons I mentioned, mountains, outdoor recreation, but we also have a great food and brewery scene here as well. That visitation has a large impact on the way our city operates.

It has an impact on our infrastructure, our housing costs, which continue to rise along with a lot of other cities which are experiencing those immigrations that Diane mentioned earlier from larger cities. You can say the city of Asheville is a city of superlatives. Over the last 15 to 20 years, Asheville has been named on a number of top 10 lists because of its food, its beer, its outdoor recreation, and for tourism.

But to really understand how Asheville got to where it is today, we have to really take a look at its past. And in the mid 1800s, the city of Asheville was a very, very rural place, but still it was becoming an economic hub for Western North Carolina. And it was at the confluence of a number of different industries such as agriculture, mining, folks that were logging for timber, and then an up and coming tourism area as people came to Western North Carolina in the mountains seeking that fresh mountain air to cure ailments such as tuberculosis. And at the time, the Western North Carolina railroad was built in the late 1800s, and that started to bring more money, power, and influence to the city.

And in the early 20th century, we started to build lots of civic institutions such as our City Hall which was built by Douglas Ellington in 1929 and it's seen behind the obelisk just to the left of that obelisk in the center of the screen. We had one of the country's first electric streetcar systems. But we started pouring a lot of money into parks and other institutions which started to create a lot of debt in the city. The city's lifestyle during that time and the debt was captured very well in Thomas Wolfe's, Look Homeward, Angel.

And then, bam, on October 29, 1929, the city and the whole entire country experienced the beginning of the Great Depression, where stocks lost 80% of their value. And in the city of Asheville, the city incurred roughly $8 million of debt, which is equivalent to over $120 million of debt today. Because of that debt, the city, especially its downtown sat in dormancy for almost 50 years and all of our historic buildings were boarded up. There were high crime rates and prostitution and no one really came to the downtown.

Especially with the proliferation of the automobile and suburban malls and especially malls in the 1960s and more suburban style development in the 1970s, that really had a negative impact on the downtown of Asheville. It wasn't really until the early 1980s where the city actually, over 50 years paid off its debt instead of entering into bankruptcy. And in the early to mid 1980s, there were a few small time owners and developers in downtown that really saw the value in its historic buildings. And it saw value in investing in the small businesses that still remained in the downtown such as some of our coffee shops and retail stores.

So between that-- and some local bank's like the Self-Help Credit Union, the city and these investors started providing low interest loans, trying to get small businesses to expand. And we also took advantage of historic preservation tax credits to preserve and bring back some of our historic buildings in downtown. So today, this is a snapshot of what the city of Asheville's Downtown looks like. It's a very vibrant city.

I mentioned all the tourism we experience, we have a lot of outdoor cafes and breweries and museums, great food and drink. And that's captured I think very well the growth of the city and what it looks like compared to the county in this graphic. This is actually prepared by Harvard Graduate School of Design alumni, Joe Minicozzi of Urban3.

He was a colleague of mine in the city of Asheville. This graphic represents the tax value per acre of land in the city of Asheville compared to the rest of the county. And you can see in the middle of the screen, there's a lot of taller bars in a purple reddish orange color. The purple color represents a tax value per acre of over $20 million. This represents a lot of the hotels that we have in Downtown, but we also have some other areas of the city that are of higher density and of more urban mixed-use areas that also are highly productive from an economic development and tax perspective, especially as compared to the rest of the county in the region, which is very rural, the further you get out from the city.

This graphic zooms into the Downtown and compares this economic productivity and increase in total tax value of property in Downtown Asheville between 2008 and 2015. And again, that purple color represents tax value per acre of over $20 million. Red and orange also represent very high productive tax parcel's. If you looked at this type of graphic compared to your typical suburban sprawl, highway commercial corridors, these bars would be much lower. And I think part of the story here is that over the last 15 to 20 years, especially, we've started to build a lot more hotels in our Downtown and in the region.

We actually have approved over 8,000 total hotel rooms in the city of Asheville and between 2015 and 2020, the city council approved over 3,000 hotel rooms alone, which again, is a lot for a city the size of just 94,000 people. And the impacts of tourism when you see the marketing materials, these are the types of graphics that you would see, a very active and vibrant Downtown at least pre-COVID with a lot of concerts, a lot of music, like street performance, and a lot of vibrancy. But historically, when we tell the history of the city of Asheville, we've often neglected to tell the other side of the story. That although we preserved a lot of acreage of our Downtown area, the city also experienced actually the highest area of urban renewal impacts in the Southeast. And through urban renewal, the city and that program helped to displace thousands of African-American residents, Black owned businesses, churches, and Black schools and other institutions.

And this is the side of the city and the story that for again, for the last 15 years, when we talked about the success of Asheville, folks rarely spoke about the real history of urban renewal, as well as red lining in the city. Like many cities throughout the country, the Home Ownership Loan Corporation assigned the credit worthiness of neighborhoods and red lines particularly, Black neighborhoods within the city, which were deemed to be more hazardous to provide loans and thereby decrease the value of homes in that area. As we know in the United States, home ownership as a major way of building wealth, and that's had a really negative impact on Black and Brown people in this country.

So what we started to do in the last few years is try to better understand the lasting impacts of the urban renewal programs of the 60s and 70s, as well as red lining in the 30s and 40s. We started to overlap those urban renewal areas, red lining areas with neighborhoods that are experiencing change, these are neighborhoods that are going to be more vulnerable to gentrification and displacement and we started to do a deeper dive into taking a look at some of the socioeconomic impacts of those neighborhoods and why we're experiencing all this displacement. We're looking at changes in income and education levels, home ownership rates, and rent in those areas.

So when we now tell the story of Asheville, where we now have to include that we're on some other top 10 list that aren't what you see in our tourism marketing materials, where according to a Realtor dot com article from a few years ago, Asheville was the second fastest gentrifying city in the country. We have increasing housing prices and values that were already occurring before COVID and we're getting a lot of immigration from folks leaving larger cities or leaving from California and high property taxes and wildfires and those sorts of things and seeking a progressive city in the Southeast such as Asheville. This has all had an impact on the increasing and widening disparities that we see amongst Black and white households in the city. We have an ever widening educational opportunity gap and increasing disproportionate impacts on health and climate change vulnerability, especially in BIPOC neighborhoods.

The city of Asheville was very much like every other major city in the country, last year experiencing social justice and civil unrest after the murder of George Floyd. Although the city of Asheville has been trying to embed equity as an organization over the last few years, 2020 had a profound impact in what we're prioritizing as a city in terms of trying to improve the conditions for Black and Brown people in the city. As Eve mentioned, in July of 2020 last year, the city of Asheville was one of the first few cities in the country where our city council passed a reparations resolution. In that resolution, the city took responsibility for its participation in slavery and urban renewal and red lining and all these racial disparities that I mentioned, especially in health and income, in our justice system. And we've started to kick off a two year planning process for reparations that will help define what reparations means for Black community members and we'll start to develop a number of strategies related to public health, economic development, our justice system, and housing. One of those initiatives that we recently approved was related to hotels.

So in other cities, at least in Illinois, being maybe a very familiar one, Evanston city, I think the first city that passed reparations and it's starting to actually fund the reparations fund based on a tax on marijuana. In the city of Asheville, our bread and butter is tourism. So during the pandemic and actually before the pandemic started, we began a 1 and 1/2 year moratorium on new hotel development. During the pandemic we started to scratch our heads and wonder, is this the best thing to do when we're not experiencing tourism? But we soon realized by the fall of last year that our occupancy rates in hotels were at almost at the same level, if not higher than even pre-pandemic levels.

So we knew that our bread and butter was really taking a look at new hotel development in the city and trying to leverage that land use to try to receive some of these community benefits and try to fill this gap that we're experiencing in the city. So as part of our new hotel development regulations, we developed a new reparations fund in which as an incentive for hotels to be reviewed and possibly approved as bioright use by city staff instead of going to our city council in a more unpredictable, uncertain, and politicized process, if a hotel provides a certain number of public benefits in which we've assigned different points to, then it could be approved at that city staff level instead of going to our city council and going through that longer development review process. So what we're asking hotels to provide, some examples of public benefits include funding this new reparations fund, either building or helping to fund affordable housing, paying living wages to their workers, having employee owned business or being a B Corp certified type of business, contracting with minority women owned business enterprises, integrating green infrastructure and green building elements into the design of their building, and finally, we are giving negative points when businesses and housing are displaced. And basically, if a number of points can be met, then that hotel can be approved at that administrative level. Another way that we're looking at land use and development and zoning through an equity lens, is through another project which we call urban centers rezoning.

We all have this style of development in everywhere we live throughout the country, where we have these underutilized surface parking big box stores and styles of development along our suburban corridors, and over the last few years, we've been working on trying to redevelop these areas and try to guide redevelopment in those areas to take on a more urban form that's more mixed-use, that incorporates more housing and affordable housing. And this is an example of one of the sites we're looking at that contains a former Kmart site, typical suburban sprawl type of development. This particular area is on a higher frequency transit corridor closer to Downtown, has a lot of redevelopment potential, checks off all the boxes for the type of more urban mixed-use style development that we'd like to see along these commercial corridors.

This area though was unique. You can kind of see some of the rural hinterlands just adjacent to this site and how quickly it becomes rural in the city of Asheville and the surrounding county. But when we started to look at these sites, we took a deeper dive into the neighborhoods that might be impacted by redevelopment of these areas. In Asheville, in this particular site around this former Kmart property, we started mapping areas in the surrounding community in the county, and within a quarter mile we realized that this one neighborhood called the Emma Neighborhood had a high concentration of Latinx community, Hispanic community that owns mobile homes and manufactured homes, many of which are on land that's rented and can be easily displaced if there's a surrounding development that might encourage redevelopment of that surrounding neighborhood.

It's also in an opportunity zone, which that neighborhood fears quite a bit that after speaking with them, they don't want to see really any improvements happen even a quarter mile away at a former Kmart site on this commercial corridor, any types of sidewalks or infrastructure improvements might make their community more desirable and more vulnerable to gentrification and displacement. So I've highlighted the manufactured housing areas in yellow to the north and then just to the south, the Burton Street Neighborhood is historically an African-American neighborhood that has been historically impacted by highway building decades ago and a soon-to-be impacted again by an expansion of a highway called I-26 in Asheville. So we realized that this area wasn't as simple as just trying to develop a new zoning code that would help to spur redevelopment, but we had to look at this area differently through an equity lens and try to ask ourselves what equitable development looks like for an area like this. So what we did for this particular urban center, is we started going through mapping exercises, we prepared a map which we call the neighborhood vulnerability map, which borrowed some methodology from the city of Portland, where we looked at various socioeconomic conditions of neighborhoods such as income and education levels, race and ethnicity makeup, and determining the vulnerability of that neighborhood or susceptibility to changing over and being impacted by gentrification and displacement.

So obviously, a large-- like next neighborhood, like the Emma Neighborhood and the Burton Street Neighborhood, which has historically been impacted by the growth and development, this was a prime candidate to apply a racial equity toolkit analysis. This is analysis that was guided by the Government Alliance on Racial Equity or GARE, in which the city of Asheville is a member. And we started looking at the history of these neighborhoods, how they grew, what type of developments have impacted historically these neighborhoods, and started really reassessing what our desired outcomes were for these urban centers.

And particularly, we've been working with a group called PODER Emma which has a really great model of ownership, a cooperative ownership model where folks of this manufactured housing neighborhood actually own the land through a co-op beneath them which almost acts as a land banking or community land trust to help preserve that land in perpetuity so that it might slow down impacts of displacement. We're also working with another group called the Legacy Neighborhoods Coalition, which includes representatives from all of our Black and Brown neighborhoods in the city of Asheville. And we're taking a deeper dive into what co-designing actually looks like for these urban center sites.

Rather than giving a presentation having these communities respond to the form-based type of code that we're looking for these areas, we're looking at what co-designing looks like so that any type of redevelopment in these areas will be more equitable and will hopefully serve some of the community's needs. We're also developing a number of anti-displacement strategies that could be applied not only to these urban center sites, but hopefully to other neighborhoods throughout the city. And with that, I appreciate it and I'm handing it over to Faranak, thank you very much. Hello, everyone.

Thank you Diane and Eve and all the organizers for inviting me and the audience, and it's a pleasure to be with you all. So I'm going to share a tiny bit of the aspects or insights from the book that was already mentioned, Global Heartland, which is about a small town in central Illinois. So it's one aspect of that story that I would share with you here.

So let me share my screen and take you to Beardstown, Illinois, which is a town of 6,000 people, four hours South of Chicago. The story of Beardstown, Illinois is a story common with many Rust Belt cities or towns. The industrialization and the population that started in 1970s, and as we can see in the graphs they were losing population. But sometime around 1990, the only industry that was left in town, the meatpacking plant, had lowered its wages and added one shift more, and couldn't get local workers to accept it look it's low wage jobs and started reaching out to a diverse workforce.

Some of them immigrants from Central America, most predominantly Mexicans in the 1990s, and by 2000 started recruiting among West Africans, predominantly Togolese and later in early 2000s, switched to African-Americans recruitment from Detroit or Puerto Ricans from the island. And that was the way this downward depopulation of town was basically corrected and the population got stabilized in its numbers. But what is important is that this also meant a dramatic shift in racial and ethnic and linguistic diversity of talent. So a place that was by census of 1990, 99% of respondents have declared that they were non-Hispanic whites, by a census in 2010 they were down to 61%. So you can see that this was a dramatic shift that happened in a short span of 15 to 20 years. The other thing that we need to know about Beardstown, Illinois, is that it was one of those sundown towns as James Loewen has called these towns in the North of US that wanted to have the African-American labor force but they didn't want them to live amongst them and therefore the threat of violence with signs like this posted outside Beardstown.

They kept the African-Americans, as well as any non so-called white population out of their town. This is not distant to history, the Klan even had a demonstration in response to Cargill's recruitment of Hispanics and Africans and diverse workers by 1995 and so was marching of KKK through Beardstown in 1996, the sectarian violence that happened. So I just want you to keep in mind that this town was a hub of industries that went through the industrialization and it was an all white town that through threats of violence was kept all white before this dramatic shift happened, OK? So in the book I try to deal with many aspects, grapple with many aspects of this complex story of transformation. What kind of transnational forces produce globally mobile labor force for industries like meatpacking and places like Beardstown? What kind of transnational practices of care allow migrants to displace labor force to accept these low wage jobs that locals don't accept? As well as what are the dynamics of race, labor, and space? How diverse new groups renegotiate their relationships with each other as well as with the local native population. So these are the questions that I deal with in the book, but for the purpose of this brief presentation here, I'm going to focus on one point, does local context matter in the emergent politics of in-placement? I don't use the word placemaking as comfortably because it's associated with different stories. So does local context matter? When I turn to the existing literature on globalization and placing of globalization, urban scholarship that has dealt with the issue of how globalization works out in the local context, it is dominated by literature that has looked at this issue through the lens of metropolitan areas.

Metropolitan centers, Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, or the so to speak global cities list has been dominant in how we understand the interactions, the ways in which these new populations deal or find a place in their places of destination. But as we know, when we put a focal light in a place, you must have noticed that we see that object very well. But we also create a dark ring around it, the blind fields. So conceptually, I think the power of analytical power of global cities theorization which is important has also created analytical blind fields about non-metropolitan areas, in places like Beardstown. And what is the experience of globalization and place in those non-metropolitan areas? And that is what I want to share with you in the next few minutes.

But let me first clarify one point here, I refer to small towns in the Rust Belt as non-metropolitan areas, which is not to be interpreted in some traditional sense as if these are non-urban areas. Small towns in the US have always been places of flows of in and out migration, of displacement, to start with Native Americans, and of in-placement. Therefore, emergent urban scholarship however, with its metro-centric theorization silences a range of places and place-based politics, such as those that, I will discuss with you here in Rust Belt's small towns, OK. So with that introduction, let me take you to Beardstown and share with you what I mean by local context and the politics, informal politics that works out in that town. So this is Downtown Beardstown, and if I take you around Beardstown, you will see that there is of course no sign of what the other Rust Belt ghost towns are.

There are very few boarded up houses, houses are refurbished, but also you don't have segregated neighborhoods. In Beardstown, the residential integration has been accomplished, the index of dissimilarity is indeed lower than that for New York or Chicago or other metropolitan areas. People, Latinos that were brought in to join the city, Africans are all over town. You don't have immigrants in mobile homes, in a mobile home park outside the city, the patterns that we see in other large metropolitan centers, so the integration of a diverse population across the town is an important point to be noted in Beardstown. Also, in other towns you-- of course, with depopulation and loss of younger population, you have the schools being boarded up in or closed, but in Beardstown there is a new school built.

But most importantly, they don't have the English as a second language, where you take the non-English speaking kids out of the classroom and segregate them to a different class and ESL classes. They have an immersion program or two-way language program, where the English-speaking kids, kids that speak English at home have to learn half of their curriculum in Spanish and the Spanish-speaking kids get half of their curriculum in English. This immersion is very important and it's something that even in big cities, it's hard to accomplish. But as I will talk about-- teachers movement accomplished this.

This was not something from above that was dictated, it was something that the teachers went then door-to-door and among all families got consent for adopting a dual two-way language immersion. And it has been incredibly important in the kinds of integration that we talk about linguistically, as well as ethnically, culturally, racially, et cetera. Another side of Beardstown story that is outstanding, is that they did not necessarily join the melting pot, sending their kids to baseball for example. But they created spaces for the sport of their choice, which was soccer.

So Africans and Mexicans and increasingly the US and European descent kids or what we call racialized white kids, are also joining these leagues. But these are leagues for adults and youth in soccer. They created a space and cleared up fields for soccer leagues, 11 soccer leagues recreated, et cetera, as well as performance of cultural identity practices. It is something again, I want to remind you. This was a sundown town, where you couldn't even spend the night in this town.

And here, not only these diverse people arrived and stayed, were recruited and stayed, but they gradually, through a series of special struggles, right? Managed to assert themselves in public space through sports, as well as cultural celebrations. Another factor that has facilitated integration is the absence of child care services, the plant, the meatpacking plant company doesn't have a child care service for employees, for workers and they have found home-based childcare, which is mostly run by Mexicans and the African new arrivals have been sharing their service or taking their children there. And soccer has been a place to create understanding, mutual understanding, cultural understanding for men predominantly, in the child care home-based childcare centers.

That opportunity of cross-cultural understanding has been provided for the rest of the family. I want to stop here and say, if I looked at the formal politics, at the city council composition, they are all white Muslim men, all English speaking. If I only looked at the plant, which is classic, textbook, putting one ethnic group against another, one linguistic group against another, I would have walked away with from Beardstown, Illinois, with the generalization that this is the typical site of ultra-exploitation by capitalism in an isolated small town that workers are brought to and hyper-exploited, which they are super-exploited, of course. But the literature of metropolitan urban scholarship of so to speak global series lens, was not equipping me for understanding what is happening here, because if I had the expectation of large-scale activism, right? Or formal politics of forming collective action and taking over formal channels of participation, I would see none of that here and I could easily deem it as a hopeless space. But by looking at nuanced ways and nuances of how people have claimed the space and also negotiated their relationships with the various specificities of that site.

So let me get you for example to the residential integration. The fact that this was a sundown town that anyone who was not white was zoned out of Beardstown, meant that there were no pre-existing neighborhoods for Latinos, for African-Americans, for this and that. And therefore, when new labor was recruited, they spread out all over because there were no pre-existing pockets to be plugged in. So that-- I'm not advocating being of a sundown town or being all white town, but I'm saying is where the specificities of the site that allowed a different pattern that maybe in metropolitan areas doesn't happen because there are pre-existing segregation's. The low cost affordable housing allowed Latinos to become homeowners, refurbish old homes, and then rent it out to Africans new arrivals and interracial rental practices. The fact that there was only one school in Beardstown allowed teachers movement to succeed in convincing all parents to a dual language we mentioned.

Maybe if there were multiple schools, as is the case in often larger cities, there would have been a segregation happening. Racialized white parents would take their kids to one school and the others segregated, but in Beardstown because of the specificities of that site, teachers managed to assert and institutionalize a dual language program, which has been one of the key elements of the way in which integration has happened in Beardstown. As well as I talked about the soccer and childcare program.

And so these are important to keep in mind, how the particularities and the specificities of a site would allow us to understand and see the nuances, ways in which in a place that the process of revitalization, what might be very different from somewhere else. Coming to for the next minutes, I want to take and talk about materiality of place. This is a very important-- how I frame it as materiality of place is that, if we think about it, in the early 19th and 20th centuries, in Chicago School, there was a belief or a basically theorization of what we call a physical determinism.

We have moved from that theoretical position, physical determinism, to something that I think has been at the cost of valuing understanding, paying close attention to the physicality of a place, right? And by materiality of place, I mean both those physical characteristics which could be size, but also the social and historical forces that shape those particular possibilities that exist in this town. And here, for example, the relations of histories of race and labor have created a particular site, right? And that, the materiality of the site, which is in Beardstown, would allow a different kind of politics. So by looking at the informal everyday politics of people, we can discover those potentials that exist in a place and not necessarily look for-- not miss it if you are looking from the lens that has been created or tailored among metropolitan areas. I call really what we often miss in that post-materiality of place and seeing that the specificities of a site as a tendency that recorded post-material theories in urban, we only see how a place reacts in relation to for example functioning of global capital. My time is over. Moving beyond the metro-centrism of globalization and urban scholarship allows us to see how local place matters in the emerging politics of in-placement.

What happened in this town might not happen somewhere else but there are relationships that can help us to generalize and theorize, not through the lens of metropolitan areas, but a broader sense of place. Thank you, I'll stop here and I look forward to the discussions and comments. Thank you Faranak, I'm Andrew Freear, I'm going to very quickly share screens with you all I hope. I'm obviously delighted to be here. Thank you very much for the invitation. I'm going to try and go swiftly so we can have a chit-chat at the end.

I'm going to say a few words about the rural condition, then talk about the region I live in, the Alabama Black Belt. And frankly for me it's-- to be able to talk about a place that you love, it's always wonderful. So that's easy for me. And I'm also happy to try and lift the lid off our particular rural condition, but more importantly, make a plea for the symbiotic relationship of rural and urban. So I come to you today from Newbern and I live just a little bit up the road from here. This is downtown, in our town of 178 people, but it varies, depends who you ask.

And we reside in a county called Hayle, 16,000 inhabitants. OK, OK, now it's working, sorry about that. So quick geography lesson. Obviously, the state of Alabama is just down here. OK, state of Alabama. Hopefully most of you know that is, probably a lot of you want to wipe off your memories.

We of course, did a great thing in our history, managed to get rid of the most valuable piece of the real estate to Florida. It's on the Gulf of Mexico where we have very hot and humid summers and humid wet winters. The most important part of this map to see is that I work in a place called the Black Belt which is at the bottom end of the Appalachian Mountains, and also was at the confluence of a prehistoric lake. And when the lake receded, it left some beautiful black dirt in our region and gave the name to the place, the Black Belt.

So it's not because of a bunch of Black folks living here, but it's simply because of the beautiful black dirt. Newbern is in West Alabama, we're on the Western edge of the kind of civil rights triangle of Birmingham, Selma, and Montgomery. And frankly, that history is so immediate to us, we live with the consequences of that every day. But just a little bit to say something about the rural real quickly, delightfully, the US census defines the rural as what it's not.

So it's the leftovers, that's not cities fantastically enough. But in actual fact, 60 million people live in the leftover, which is essentially a population about the size of Italy. And contrary to common belief, at least statistically, it's not dying, it's remained stable for the last 110 years, whilst the urban conditions obviously with the industrial revolution has exploded. One in five live in the leftover unless you technically occupy about 97% of the US land mass. The problem is that generally rural in relation to city has always been seen as an extraction landscape, not want to be sustained hand-in-hand with the city, but seen as fuel for the city.

It's a place where a lot is taken away and little is given back. And it's not a coincidence that this leads to places of endemic entrenched poverty. It's been particularly bad for the Appallachians, the Colonias, and of course the Delta. My home county of Hayle has a poverty rate of 28%.

The poverty around here doesn't really discriminate, but perhaps a more shocking fact, is the county East of us, Perry county has a child, poverty rate of nearly 60%. Do we hear about that? Not very often, right? Perry county was the birthplace of Coretta Scott King, wife of Dr. King. The situation has been so bad that until four years ago, Perry county was under its own lockdown because of an outbreak of tuberculosis.

So it always amuses me when politicians come and laud the Civil rights achievements and its association to West Alabama, but never address the real current local struggles. My sense is that generally, rural folks just want what you urban folks have. They want access to good jobs, they want access to good schools, they want access to good safe drinking water, and good sewage systems. About 20% of American households use on-site septic systems. And of course, these are predominantly rural.

Alabama has more than 800,000 private septic systems for people not hooked up to a municipal wastewater system. And about a quarter of them are actually failing. Folks also want access to decent reliable broadband internet. This is the dashboard of details from my satellite provider, where they proudly announce that the service is 1140% slower than the national average.

So I ask you, can we have a good connected engaged citizenry in this situation, with such inequality of communication? Rural folks also want decent housing. Rural housing is aging. 20% of housing in my region is substandard which I have to say in my belief, is a wholly underestimated and inaccurate number. The answer to housing affordability in rural areas is currently trailerable, that's financed like an automobile and has very short life expectancy and certainly represents no kind of long-term investment.

But rural housing also needs to be treated as a different animal to urban housing. Unlike urban housing, rural housing simply cannot be about wealth creation. You don't buy a house to fix it up and flip it, that's simply not the demand. It's not a lucrative moneymaker. So we have to think about rural housing as a different beast, as a life building act that allows for expansion and addition, a home building model that you can add to when you have the resources and when the family grows.

But the key is not to undermine the existing home when you add to it. So back to West Alabama, I live in a forest. Ironically enough, it's the breadbasket of the US timber industry.

The problem is that a lot of that land and timberland is owned by individuals and corporations who live outside of Alabama. When we try to raise real estate taxes to help education, you can imagine how rabid the lobbyists are to keep those taxes down. Northern Alabama is also home to forests and pig farms, a lot of them. In our West Alabama most of that beautiful Black Belt soil has been washed away or destroyed by mono-cultivation and chemicals.

What's underneath is an expansive red clay that's difficult to farm and to build on. Locally, about 60 years ago, they discovered that if you dug a hole in this clay and filled it with water, and let the water supersaturated the perimeter, that it self seals. So you get a cheap way of making a pond and then of course you fill it with catfish. So if you eat catfish in Boston, it's likely it came from here or in the Mississippi Delta. Local farmers really work hard to diversify depending on prices, and are typically farming catfish, beef herds, soybean, and some of the root vegetables. Some folks have today ironically reverted to cotton.

So it's a tough place to make a living. They really are asking the question of how do you live off the land? It's an authentic challenge. Hayle county's not a place that's propped up by elderly retired folks and there's very little tourism. Truth is, job wise, many locals will commit one to two hours to work in the service sector in our nearest cities like Tuscaloosa and Birmingham.

The landscape and weather in Hayle is also very fragile. We live in Tornado Alley. We had two major tornado events in the last month and they're getting more frequent and stronger, which is a sign of things to come.

Excuse me. Religion is also everywhere. Sunday truly is the most segregated day of the week.

And in schools, they suffer directly. The fallout from segregation and desegregation in the 60s and 70s, when the whites went off and built their own private schools, so the resources and schooling energy is often divided. Now to Newbern, a dot on the road on Highway 61 that was originally a medicinal water spa town and was soon followed by King Cotton. In downtown, which is ironically quite urban with narrow street frontage stores cropped up closer to the road, there are three fragile institutions-- The School of Architecture, Post Office, and Mercantile.

The School of Architecture is quite a lot different to Gund Hall. We bring young designers into a rural context, open their eyes to challenging opportunities and the advantage of the rural context is it's a very can-do culture, where you use what you have around you. Next door is the Post Office and Mercantile our social centers. Post office was recently reduced to four inconvenient hours a day, I suspect to try and get it to close, of course. And then there's the Mercantile, the only place locally to buy gas, orange juice, and Coke within 10 miles. Then there's Greensboro the road 10 miles North, which is our nearest real town of 2,500 people.

It was a cotton town. This area around the late 1800s was one of the wealthiest in the world. The barons would have their plantations in the country and then weekend homes in the big town. At the outbreak of the civil war, the local militia was so strong that the Union forces who normally burnt towns like this down, were persuaded to go around the town and left it alone.

So much of the architecture is here and intact today. Main Street has good buildings still, but the pace of change is slow. This is actually 80 years on from the previous slide.

The [INAUDIBLE] old commercial Main Street runs into mansions. But in the 60s and 70s and the early 80s, the life of the city moved from Main Street which is shown in red, to State Street shown in blue, mainly for parking and drive-throughs. Banks, gas stations, and fast food have thrived. The industrialization of farming has taken its toll, but not just on the agricultural landscape, but on the townscape itself. Now Greensboro looks like anywhere USA, and as my wife would put it, it's very sub-rural.

And of course, the deep irony is that folks drive 10 miles to Piggly Wiggly to buy processed, prepackaged food in a rural region of rich farmland, you simply can't buy freshly available local vegetables, and fast food of course is also much cheaper than grocery stores. Inevitably, that has its health consequences. By 2030, It's predicted that this region will be 60% to 100% obese. Now, this is not a problem, it's actually a catastrophe for us all. So who do we work with? In this place, local leaders are very accessible.

There's very little bureaucracy or firewalls. I actually have most of the numbers on my cellphone. But they have very few resources for public good, health, and maintenance. One thing you all should know is that locally, there's no money to resource policing building permits or zoning. So one of the few organizations, being a state organization, we actually built to the International Building Code as other folks actually really don't even know that the building code exists frankly. But these guys are crying out for help with projects and programs for health and welfare, and particularly for the youth.

So ordinary folks who have ideas and can chase resources can get stuff done and be very influential. Counties are run by commissioners and a probate judge, towns by councilors and the mayor. We've worked with these two mayors for the last 15 years.

They're are two folks with very different backgrounds, both born here, both had very different experiences growing up here as you can imagine, both left and both came back, came back home. Woody on the left is Newbern's mayor. He went off to Mississippi, got married and grew a very large HVAC company and refrigeration company. He came back 20 years ago, established a new company and is now the main HVAC and Plummer in Hayle county.

And he works like crazy, you you've never met anybody that works as hard as this guy. As does Johnny B our mayor of Greensboro. He went to Tuskegee University, got himself an architecture degree. We're very proud of him. He got a pilot's license, taught flying, went to DC, became a high school teacher and was a code enforcement officer in his career.

Back in Greensboro, he runs a construction company and a mortuary. Now I have to tell you they are actually separate entities. They're both, as I said, both workaholics and I have no idea why they do what they do. They really not paid for all the aggravation that they get.

But they're remarkable individuals. They're both open individuals to community groups and organizations, as instigators of ideas. But they're both realists.

They both accepted that they're not going to get big businesses into Hayle county, and they've accepted that no growth is actually likely to be a fact. But what they really focus on is bringing a quality of life into this small community, for its current inhabitats and that's really one of the reasons we work with these folks. So through persistence, here ordinary folks can make things happen very directly. Ideas must come from local folks from within, from the inside. So real quick, I'm going to give you an idea of how we've been the energy and wheels for some of these ideas and a little taste of how and why they happened. We worked with this group on a fire station, which actually was the first new public building in Newbern for 110 years.

After a series of house fires, insurance rates went up, which hit folks in the pocketbook and actually gets folks to do something about it. So they established a Newbern Volunteer Fire Department. The building actually houses trucks which needed protection from the freezing, because they carry water to the fire, as there's no rural fire hydrants.

So the building is passively heated and cooled. And the other thing to say about the building is, we were trying to celebrate a very diverse Black, White, and Mennonite Organization, so for those folks there was no preconceptions or tickets on the space. So it was really important to celebrate it with a new building. The building was actually so successful, the fire department needed a classroom for training. The town needed a place for the council to meet and for democracy for voting. So the mayor suggested the town hall and civic center and he found the seed money for this and we became the legs for the project.

Then these lovely ladies, old school teachers decided to instigate a library because of the shitty internet and the death of after school programs in our little town. The old bank building which had been the temporary town hall became available. We helped them turn it into a library. The road back up the road in Greensboro, this is a council in session, as you can see you can see Johnny B and his counselors sitting at the council chamber. Honestly, this is an example of the kind of help we are able to give and something that other cities probably just take for granted. One of the guys in the audience actually wanted to build a chain store in a residential area of the town and guess what? The city actually had no zoning ordinance or zoning map.

So the council was actually in no position to say yes or no, they just frankly just kept stalling him. So our organization actually put a very basic ordinance together for him and they were able to move on and thankfully said no, but they were able to move him to a different place in town. On another project, this group of citizens got together and proposed the city of Greensboro needed a boys and girls club, for at risk kids after school with parents getting home late from work and kids wandering the street. To show its importance, the chair of the board was actually the police chief. They came and knocked to us and asked us advice on where to put the building.

We actually suggested the city armory. The city had just bought the building from the National Guard and the other big ticket high dollar item in the building which was actually a gymnasium. The city had plans for a recreation center and I suggested that the boys and girls club approached the city and ask about the possibility of sharing the gymnasium and the recreation center's off hours. The city asked us for a four-years phased move in plan and we gave them that and the project and behold actually happened.

The boys girls club became a project that we designed and built and it connects to the gymnasium. It was completed a couple of years ago. The mayor was really pleased with the fact that we actually had a four years phased plan for a budget that was put in front of him, and he doesn't normally have the ability to plan ahead or resources to do so. The last thing to show you that offers of the opportunities that may not exist in other places, and maybe could be seen as a critique of larger cities. Lions Park it's the largest park in Hayle county, 40 acres.

It's actually the only place locally where Black parents coach white kids and vise versa. The mayor in the Lions Park committee came to us 15 years ago and asked us for a multi-year plan to redevelop the park. So for 10 years, we've revisited a flexible strategic plan for the park with the committee. Each year up to $50,000 seed money to design and build a piece of the park.

So I would suggest there's a few advantages to this. With staying power and determination, it makes it financially achievable for a small town like this. On day one, it doesn't mean that you have to have a multimillion dollar bond in place to finance the project.

You can learn about the maintenance and bite size chunks instead of all at once. For example, we started with ballfields. And also you don't have to have a grand finished master plan in place assuming that what you need, which all assumes that what you need at the end right at the beginning, so unridiculous So perhaps for us, the piece we're almost proud of is the Skate Park that Tony Hawk sponsored, that we never dreamed of on day one. So I'll shut up and let's chat. That's Hayle county for you. I think, well, so Eve and I were just realizing we were so super ambitious with this event because we were so eager to hear from all three of you and you did not disappoint.

So much amazing material and, of course, no time. So we had originally thought that we would ask some questions to the three of you and then maybe share some of the things on the chat, and I think what Eve and I will do-- you guys are not off the hook. You're going to come back another time and I wish we could be here in Cambridge as Todd has mentioned and maybe we'll be able to do that actually, have a day conference or something. But what Eve and I will do is, I'll just make, I think an observation about what I've learned from all of you, that we can ruminate on at the GSD, with our students and our faculty as we think about moving towards the future. And so one thing that I want to say that really strikes me that you've really made clear, Faranak, all of made clear, the importance of not making extreme assumptions about differences between big cities and small towns. That some of the very same issues about race and lack of resources and poverty, they're there.

But what's also striking to me about all of your presentations is that there seems to be some movement forward. I'm thinking about what Todd has mentioned about the reparations and about the affordable housing, so we have some of maybe the racial inequalities, history of racism, et cetera but we also have some movement forward. So a question that I'd like us to think about and send some emails later, we can talk about it again, is whether there's something about the nature of these contexts where the process is different.

That things can get done in a different way than maybe in a large city with the same type of experiences. Faranak mentioned the spatial

2021-05-02 10:57