2022 Frontier Forum - Not Fade Away: Dark Tourism & City Government

[MUSIC PLAYING] - (SINGING) Them good old boys were drinking whiskey and rye singing, this'll be the day that I die. This will be the day that I die. They were singing bye-bye, Miss American Pie.

Drove my Chevy to the levy-- - All right. I think we're ready to get it rolling. So good afternoon, everyone. Welcome to the 42nd Annual College of Social and Behavioral Sciences. - They still have the music going.

- Yeah, I figured they'll kill it while I-- We're good? OK. Check. Check. That wasn't Buddy Holly playing, anyway, so turn it down. So again, good afternoon.

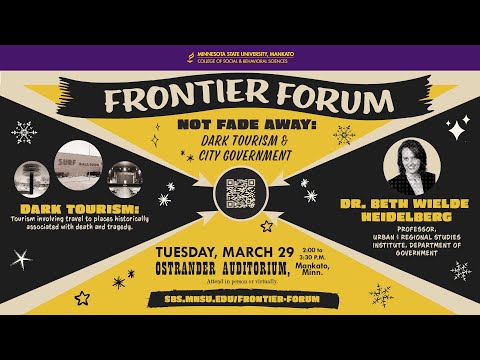

And welcome to the 42nd Annual College of Social and Behavioral Sciences Frontier Forum Lecture-- Not Fade Away-- Dark Tourism, and City Government presented by Dr. Beth Wilde Heidelberg from our Department of Government. So again, thank you all for joining us, both in-person and also virtually. Just want to go through a couple of items before we get started today. If you are joining us virtually, closed captioning is available for today's presentation. So if you want to enable that feature, you need to click on the closed captioning button at the bottom of your screen.

And then choose show subtitles. Second, we will take questions following Dr. Heidelberg's presentation. So please enter your questions using the Q&A feature. You can enter your questions at any time during the presentation.

And we will address them at the end. So just to recap a little bit of history, 43 years ago, Dean Bill Webster initiated this lectureship to celebrate all research and scholarly activity in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences. It is becoming a much respected and well anticipated college and university event. Today, we welcome Dr. Heidelberg, who was selected as this year's presenter by the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences Research and Teaching Committee. So at this time, I just want to give out a shout out to all of our committee members and if you could, join me in round of applause for them.

[APPLAUSE] Thank you. And before we introduce today's speaker, I want to say thank you to all of our students, faculty, staff, and university administration for attending today's event, including Interim Provost and Senior Vise President for Academic Affairs, Dr. Brian Martensen. We are very privileged and fortunate to have Provost Martensen join us today to say a few words on behalf of the university. So please join me in welcoming our Provost, Brian Martensen. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE] - Dean Loayza got walk up music, but I did not. Well, thank you, Dr. Loayza, and everyone in attendance today, either in-person or virtually.

Thank you all for attending. The College of Social and Behavioral Sciences has celebrated now, as Dean Loayza referred to for over 40 years, research and scholarly activity, including adding this annual frontier forum lectureship. That's really quite amazing.

So I congratulate the faculty in this college for their strong tradition in valuing scholarship, activity, and research. Social and Behavioral Sciences faculty regularly present and publish their research locally, regionally, nationally for great impact. And they're recognized as experts in their field. So I'd like to congratulate Dr. Heidelberg on being selected to present this year's lecture on dark tourism in city government. In 1959, the small plane carrying musicians, Buddy Holly, JP "The Big Bopper" Richardson, Ritchie Valens, and of course, their pilot crashed in a field near Clear Lake, Iowa.

The crash forever linked the community with rock and roll's first major tragedy and established Clear Lake as a dark tourism destination. Today's presentation explores how the city turned tragedy into legacy while appropriately honoring a dark piece of history. Dark tourism has been defined as tourism involving travel to places historically associated with death or tragedy. Ghost tours are an example and are often very popular.

People are drawn to these places for a variety of reasons, many for their historical significance. People who have an interest in dark tourism may not know the mechanics or even the politics that lie beneath the surface of those sites and events. So today's presentation focuses on Clear Lake's efforts to respectfully facilitate broad public interest in the crash. And rather than trying to look to back away from its tragic past, the city has embraced its role in the tragedy and in music history, turning it into an opportunity to educate the public about music heritage and creating local policy and planning projects that respectfully accommodate the international public interest in Clear Lake's tragic point in history.

When tragedy is the main reason tourists from around the world stop to explore a community, providing a significant revenue stream that supports citizens and local services, communities must consider the ethics and the relationship between the tragedy and the revenue generated by that tourism. So Dr. Heidelberg's research provides guidance to communities dealing with dark tourism based on the Clear Lake example. I would also add that it significantly supports MSU's mission to provide impact to our region and really apply mechanisms to do applied research that help our communities move forward in advance. So at this time, I would like to welcome Dr. Scott Rademacher,

the chair of the Department of Government, who will introduce today's speaker. Thank you. [APPLAUSE] - Thanks, Provost Martensen. Today, I'm very pleased to introduce our speaker this afternoon, Dr. Beth Wielde Heidelberg. Dr. Heidelberg has been on the faculty of the Urban

and Regional Studies Institute in the Department of Government since 2004. She teaches students in urban planning, local government administration, and of course, her specialty area, which is historic architectural preservation policy. She's an alum of the Urban and Regional Studies Institute having earned her master of arts in urban planning from the department. And she went on to work for the city of Eakin.

And during that time, she completed her doctorate in public administration from Hamline University. While she leads URSI's accreditation and assessment efforts for which, on a personal note, I am eternally grateful for, she's cultivated a very rigorous research agenda focused on local governments' response to their status as a dark tourism destination. She's been published in the Journal of Heritage Tourism. And she currently has a project under review for publication. And she's presented in multiple public forums.

Her goal with this research is to help communities associated with dark tourism come to grips with their own infamy and how to balance tourist interests in the tragic events that happened with respect to the victims and the loved ones. In addition, her research seeks to draw attention to the need for balance and coordination between private sector and public and nonproffit sectors when it comes to managing dark tourism. So please, join me in welcoming the 42nd Annual Frontier Forum Lecture, Dr. Beth Heidelberg. [APPLAUSE] - Hello. It's good to see everybody who made it in-person.

And it's good to see those of you who did not make it in person, but are attending anyway. And I appreciate the kind words, Dean Loayza, and Provost Martensen, and of course, Scott, who I've been able to work very closely with on the accreditation effort. I'd also like to thank Scott Flory, the city administrator of Clear Lake and Bennet Smith who is a city council member in Clear Lake. They've joined us here today.

And I've asked them to participate in the question and answer session at the end of this program because they are going to have really good insights into how this all works. All right. So when you think about dark tourism, some things that come to mind are probably ghost stories and the ghost tours that might take when you go to a city like Savannah, or New Orleans.

Or I was just reading a book about haunted Savannah. It's quite a fascinating tale. But behind those ghost tours, there's a number of layers of administrative, and public input, and citizen cooperation that needs to happen before these tours can take place. Now, in some cases, these are fun tours.

How many of you have actually been on one of these ghost tours when you go to a city? OK, there is a good number of you who have taken these tours. And Dean Loayza was just telling me about some of the dark history spots that he saw out in Boston the Molasses Flood. So people are interested in this idea of dark tourism.

But what are those extra layers that are involved in planning and making sure that these things can be pulled off? When it's a fun tour with ghost stories and folklore, that's one animal, per se. But when you start talking about real-life tragedies, like what happened in Clear Lake, that adds another dimension to tourism planning. That creates another reality that you have to navigate and do so very sensitively. And that's what we're going to talk about today. Here we go.

OK. So before we begin, I want to lay out and build on the ideas that was established in the introduction. What is dark tourism? Well, to put a simply, dark tourism is visitation to sites associated with death, tragedy, and can be associated with ghost stories and other folklore. Basically, if it's uncomfortable, if it's awkward, and if it deals with the supernatural, in some cases, you might consider it dark tourism. So dark tourism is one of those facets that nobody has a specific answer as to exactly what it is, but you know it when you see it.

So that may sound familiar to some people. But dark tourism is something that has been capturing the public interest over the past few years. So that's the premise that we're going to build on today, the dark tourism, places associated with death, tragedy, and supernatural occurrences. Now, dark tourism isn't a new phenomena, not by any means. If you think back to ancient times, you hear about people traveling far to see the relics of religious figures, to see the bones of a saint, or a body part, or the grave site.

If you think about ancient Rome, the gladiator games, one might argue that that's actually a version of dark tourism. So it's an ancient practice. If you go a little closer to our own history, imagine this, the 1880s, Whitechapel, London, kind of dirty gritty area. And somebody's been killing women in that area.

OK. So that didn't just happen in a void. That happened in a populated area.

And people lived around these crime scenes. They lived there. They worked there. They shopped there. They saw what happened, where it happened.

Now, some entrepreneurial-- I'm stumbling over that particular word. People who want to make money, they came up with this idea, what if I let people come onto my property because it overlooks this crime scene, charge them a few bucks? That's a few extra bucks for me. And people did it.

They paid for it. They were making money off of this crime scene. And this was right after the crimes actually took place. So dark tourism was expanded during this time.

It became more of a phenomena because popular culture and media was able to tell the stories. Hey, this horrible crime happened. This is where it happened. And people got it in their minds, hey, I want to go see that. So people started visiting.

This is how we get to where we are today. The popular culture puts something into the minds of viewers. You see it on a documentary. You see it in a movie. You see it on the internet. And people want to see where things happened.

OK, so it's an ancient practice. It's a practice that's been going on for a long time. Now, for a while, people were saying, oh, this is just another subset of heritage tourism. Yeah. Yeah. It probably is because it's historic events that people want to connect to.

Great. But that association with tragedy made it different. It made it somewhat other. And when that happens, academics like myself, like Dr. Fricano, who's my department institute director

back there-- hi, Russell. We want to take things and study it further. And we want to study the nuances.

So dark tourism emerged as an academic study in about the 1990s. You don't really see literature before that focusing specifically on the mechanics of dark tourism. 1990s, you got sharply stone-- some of the other researchers in that field, starting to explore this idea. Now, this became a multidisciplinary area of study.

Dark tourism, the people interested in it were looking at the psychology behind it. Who are the people who go to see these sites? And what is their deal? Turns out, everybody's fascinated by this. You don't have to be a particularly creepy person to want to go see where stuff happens. So these places, the psychology behind it, not really identifiable. The sociology behind it, people are coming in droves. What is driving this mass interest? You've got historians who are interested in dark tourism because these dark events do shape the future.

They shape the past. They are part of our present. And they're part of the future.

So historians. Public administrators because obviously, people are coming to their cities. They have to deal with providing services for that. So it's a multidisciplinary topic, lots of interest from different facets. But as I was doing the literature review, I was fascinated with the idea that-- I'm a local government person.

I worked in local government. That's what I've studied. It's what I'm interested in.

Nobody's really taken a look at how this impacts the communities. These are the people who are living in these communities that had this terrible thing. Visitors are coming to the sites wanting to see where it happened. But the local governments are the ones that have to provide the services that accommodate that tourism. And that is not an easy thing to do. If you take a look at the bigger cities, New York, Boston, Los Angeles, they can handle that.

Boston, Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, et cetera, they've had terrible things happen, just the worst of the-- terrible things. But usually, the people visiting those cities are not there specifically for the dark tourism. They are there on a family vacation. And then they happen to take a ghost tour. Or they're there to go explore the Sears Tower or the-- I'm sorry.

Willis Tower now-- the Empire State Building. Or they're there to see other things. And then they build the dark tourism into that trip. But what about the Clear Lakes, the Amityvilles, the Holcombs.

They are not necessarily drawing international interest because of the great lake that Clear Lake has. It's a great lake. It is a beautiful seven mile wide lake.

But people could probably find that elsewhere too. What's drawing them is specifically this dark event. This is what these cities are known for.

This is what they're famous for. And that's what people want to see. So how does a local government deal with that? I am building a research body on that because nobody else has. So hopefully, we can find some common ground with the Clear Lakes, the Amityvilles, the Salems, and other smaller communities who are known primarily for their dark tourism. But first, we got to take a look at, how are we categorizing dark tourism? Because there's a spectrum of dark tourism. Research from Ashworth and Isaac and then Sharpley have created the spectrum of dark tourism.

First, you've got the funfair and folklore. These are the awesome sites that people go to get a spooky story. That's where they go to hear about-- well, they'll go to Estes Park in Colorado, visit the hotel that was featured in The Shining, or the one that Stephen King drew inspiration from.

They'll go to Sleepy Hollow, New York, Headless Horseman. They want to feel what that is like in that community. So these are the ones that are associated with stories. Burkittsville, Maryland.

Does anybody recognize Burkittsville? Or are we too far out, and I'm totally aging myself? - What do you mean? - OK. Well, Burkittsville-- how many of you have heard of The Blair Witch Project? OK, getting some more hands now. All right. Burkittsville was just a very small little community.

And then these filmmakers set their story in Burkittsville. And it was for those of you not familiar with The Blair Witch Project, it was a story about three student filmmakers who went out into the woods and encountered this terrible paranormal thing. Never came back. And it was a found footage thing.

Well, this sparked a lot of public interest at the time. In the late '90s, you couldn't go anywhere without somebody making a little stick figure and trying to freak out their friends. So when this phenomena hit, the filmmakers were like, guys, it's just a movie. Here are the three lost filmmakers. They are literally right here.

This did not happen. And it didn't matter. People still, to this day, go to Burkittsville, steal the sign because they want to have it in their own house. They go and visit the woods trying to find out where did this happen.

Guys, it didn't happen. So this fun folklore, or fun fear in folklore, this is the ghost stories. This is the very lighter, more amusement park end of dark tourism, the ghost tours not based on tragedy.

Then the second level of dark tourism on the spectrum is the unintentional events, the natural disasters, things like the Hinckley or Peshtigo fires in Minnesota and Wisconsin, earthquakes, unintentional events like an airline crash where the mechanics just failed, nobody's fault, not intentional, big disaster. So the unintentional events and natural disasters, it involves human tragedy. People lose their lives. And so it does have a different shade of dark tourism behind it. Then we get to the next level. And this is intentional and negligence.

This is where people lost their lives, either because somebody decided to take that life or because somebody failed to act, and it resulted in disaster. Some examples I'm thinking of would include the Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston. Dean Loayza, you might be quite familiar with that. It was a nightclub. And people were just enjoying a night out. And some of them got engulfed in flames so quickly that they didn't even have time to get up out of their seat.

It turned out that there were a lot of corners cut. There were building codes not followed. There was a lot of funny business behind this fire. And so while not an intentional event-- I'm sure the owners would have preferred it not happen-- but it was a negligent event.

Johnstown, Pennsylvania where up in the highlands, they had a nice little hunting club and built a dam to create a nice fishing lake. Well, the dam burst. Unfortunately, the city of Johnstown was in the way when the waters came down and basically flooded out the town and killed a great deal of the population.

So again, not intentional, but negligent. Now, this is where it gets a little bit iffy too. And I have really debated whether to create a separate category for flat-out homicide, murders like the Villisca ax murders.

The city is still dealing with the popularity of that story. And it has become a dark tourism destination. Many homicides that have taken place across the country-- I went to Milwaukee not too long ago.

And my friends and I took this tour called the Cream City Cannibal tour. And yes, I recognize the terrible distaste behind that. But it was an interesting tour and fit with what I did, so I did it.

But it was one of those things where the homicides were intentional. They were very well plotted out. And they really focused in on one area of the city. Now, what was fascinating about that one is my friends and I drove over to Jeffrey Dahmer's apartment. He was the Cream City Cannibal.

We went over to where it was. They were not able to keep the apartment up because the toxins had gotten all into the apartment. And it was a terrible thing. But there were still neighbors in neighboring buildings that held out signs that said, nothing to see here.

Drive on. So apparently, we were not the only ones who have driven past. And in some cases, people are stopping, and they're getting out, and they're crowding out the neighborhood. So these intentional and negligent events have impacted the communities to the extent where some citizens are saying, that's enough. We don't want to be associated with this. And then at the far end of the dark tourism spectrum is what I call the worst of the worst.

These are the genocides. This is the Holocaust. This is the Native American conflicts.

This is slavery. Oftentimes, these are a phenomena that extend beyond a single jurisdictional boundary. And they involve the killings of hundreds, thousands, in some cases, millions of people. The Ghana slave castles, the Cambodian killing fields, these are man's literal inhumanity to man with intention and malice. And those are the ones that really need to understand how to manage their dark tourism.

So we know that tourism impacts communities. We know how communities have to host guests. They want to be a good hosts. They want to show the best of their communities. Well, when you're planning for dark tourism-- or actually when you're planning for tourism, nice tourism, heritage tourism, the tourism that everybody's happy to see and is excited about, you have to still plan in your local government planning systems.

You've got a plan for the traffic. You're going to have increased traffic. You've got a plan for infrastructure. You've got to make sure that your sewage and your water supply is adequate in the areas that tourists go.

Otherwise, they're going to get really upset and not want to come back. And one of the goals of tourism is to attract people, so they come back, and they spend money in your community, and everybody wins. You want to take care of the increased demand in public safety. If you're having large numbers of guests in your community, they might congregate in certain areas. That will create trash. That'll create congestion.

That'll create a demand on the sidewalks. It'll erode your stuff a little bit easier. So you want to make sure that you've got police patrols out there to make sure that people aren't vandalizing, that they're not getting in fights, that they feel safe in those areas because the feeling of safety is just as important as the actual data behind safety. You want to make sure that there's fire service. So you have to plan for those things. That's just a typical local government function to make sure that your city services are accommodated.

You've got sanitation and garbage. OK, everything that I've read in my entire tourism research indicates people leave trash. Tourists like to leave trash. They like to walk on stuff.

And that leaves trash. So we want to pick up after the tourist debris. So you have to plan additional sanitation in the areas where tourists go. Marketing. Marketing in a traditional heritage tourist site is awesome. People love historic sites.

They love historic downtowns. They like to go see and experience what people 100 years ago saw and experienced. And so you can market that. That can be a drawing feature.

Hey. Come look at our cute historic downtown. We've got antique shops. And we've got restaurants. And we've got all this stuff that you can come visit.

The tourism revenue is extremely welcome. You want people to come. You want to encourage them to come.

Spend the day. Spend your money. We can use that money and make things even better for the tourist experience. OK, so that's traditional heritage tourism. But what happens when your unique niche is based on somebody's death? It suddenly takes a little twist. It's suddenly a little less comfortable.

So how do you market something like that? You can't market it the traditional way. You can't say, hey, come see where people died. Yeah, that's ghoulish. That's creepy. You don't do that.

It's not acceptable. You want tourism revenue. But is it OK to take tourism revenue when it's based on somebody else's death? That's the hard question that has to be asked. That's the hard question that needs to be addressed. And that's one of the things that I'm looking into. And also one of the most important aspects of dark tourism is the emotional impact.

In many cases, these events didn't happen that long ago. There are still living family members in those communities. There are still people who remember what happened, when it happened. And may have known somebody who was one of the victims. And so you need to consider the fact that you might be ripping open a fresh wound every single time they see an advertisement for the tourism destinations in your city.

So I've taken a look at three important factors communities need to consider as they're planning for dark tourism. And Council Member Bennett and City Administrator Flora, you probably figured all of these out. But these are going to sound familiar to anybody who's studied the Constitution. Time, place, and manner. I found that those concepts actually apply very, very well to dark tourism planning. The first one is time.

When do you start planning for dark tourism? You don't want to do it right after a disaster or right after the event. If you plan things for tourism too soon, well, it's just not good. The first thing you have to do is consider when to start thinking about tourism. You do that only after you've considered your citizens' safety, their shelter, their food, their water service, their sanitation service. You have to make sure that your citizens and the people most impacted are OK.

Also, if it's based on a criminal activity, you have to make sure that you aren't impeding an investigation because if you're inviting tourists into a crime scene, that's not good. In fact, there's a lot of speculation over the Jack the Ripper crime scenes. If they hadn't let all those tourists in, who knows how much more evidence they might have found? Because people like to take stuff as souvenirs. Yeah, slightly bad. So the timing has to be right. Is it too soon to start thinking about dark tourism planning? The next item is place.

Where exactly would you want to draw tourists? Once you've secured the scene, once you've made sure that all the evidence is gathered and that it's the right time, you've got to think about the places. Can visitors safely go directly to the sites associated with this activity? Or do you have to provide something else? So you've got primary sites, which are the ones directly associated with the event. And then you have secondary sites. Those are the ones that get you outside of the actual site and provide additional interpretation or context.

So it's not the crime scene. It's not the crash site. It's things that help you learn more about it. And we'll talk a little bit more about some examples. There's a great one in Clear Lake that I'm excited to discuss.

The third element is manner. And this is where the other theorists really come into play. What is the interpretation of the site? How is it being interpreted? Who is providing that interpretation? And do they have credible objective input? Or are they trying to sell a story? Because if you're trying to sell a story, you're going to have a different way of telling that story than if you're trying to just present the evidence. So time, place, and manner. Who's in charge of interpreting? How is it being interpreted? Who's in charge of that message? Now, I've got to bring up my three favorite examples, the ones that I've studied probably the most so far, Salem, Holcomb, and Amityville.

Clear Lake will be the case study. But these ones provide a lot of good context into three different approaches to time, place, and manner. First off, Salem, Salem, Massachusetts. I had a chance to go out there and study that city quite a bit and found that they have really embraced their role in dark tourism. First off, if you're not familiar, if somebody watching on Zoom isn't familiar, the Salem, Massachusetts case is a 1692 Salem witch trials where 2030 people were accused of witchcraft under spectral evidence and executed for it, either by hanging, by pressing, by dying in jail. There were deaths associated with this accusation of witchcraft.

Now, that obviously is a tragedy. And nowadays, we're not going to just accept spectral evidence. We're not going to have somebody saying, oh, I see a ghost.

And that is clearly-- she's guilty. Just guilty. So nowadays, what you're going to find is that we have much more need for evidence. But Salem has acknowledged that this was a terrible thing that happened. This happened in our community. This happened beyond our community and really touched the entire region.

We're not OK with this. And we're going to make sure it doesn't happen again. They created a primary site in the Salem Witchcraft Memorial. They've created a primary site by purchasing one of the buildings associated with the witch trials and turning it into a museum that provides context.

It was actually the only building that still stands that's directly related to the witch trials. So I'm really glad that they bought it because now it'll stay in the public realm. But this idea of interpreting things, it stays with the city because the city will provide a bigger picture. But Salem likes to play with this witch trials idea.

They're having fun with this thing. They have not impeded the private sector from offering tourists some destinations. And if you've been to Boston, if you've journeyed up there, it's actually quite a lot of fun.

They've got the Witch Museum and the witch trials museum where they have these almost-- well, they're scary looking dummies recreating some of the scenes. And you sit in. They show these little tableaus all around you. The city wants to support the private industry in the tourism realm.

They want to support the private sector. And so far, they've been able to do that. They are not telling the private sector how to do the interpretation. They're not trying to step on those toes. They're just saying, go see those things. And we'll provide a little bit more background into how these trials was able to happen, how the trials were able to spread.

So the city's working with the private sector. They also managed to do something that I think is critical in dark tourism planning. And this is one of the reasons why I like the Clear Lake example so much. They have turned this tragedy into an opportunity for education.

The Witchcraft Trials memorial site is sponsored by the Salem-- I want to say Discover Salem. And I know that there's a foundation in Salem. And their goal is to educate people about diversity, how you can't just point the finger at somebody because you don't like them, or they look different, or they don't have enough money.

They've turned it into an opportunity to educate people on diversity and the circumstances of 1692, why the land grabs were happening. And that's one of the reasons some of these women were accused of witchcraft. So they've used it as an educational experience. They've embraced it. But then you get the fun part of Salem. Now, they're playing on the absurdity of spectral evidence and the idea that somebody can just be accused of being a witch without really a lot of evidence.

And so they have an entire spectacle. They have an event in October that draws millions of people in. Great for the economy. Just fantastic for the economy.

But it is playing on that idea that Salem is directly connected to the supernatural. They like to play that up. They have-- what is it? --this Halloween event with costumes. Do you remember what the name of that is? OK, I'm pointing at my husband because we actually have been trying to go to this for a while.

But they have little shops that have novelty items. They have little kiosks all over the place with t-shirts and all that stuff. And so they're making fun of the absurdity of this witchcraft. They are not trying to disrespect the people who died, not by any means. But they're having fun with some of the circumstances around it.

So they have embraced dark tourism. That has been very profitable for the city. And when I say profitable, I don't mean that somebody's lining their pockets. I mean, they have been able to reinvest in the community, and do improvements, and clean up the sidewalks, and make the streets wider. And they've been able to reinvest in the community. OK, so Salem has embraced dark tourism.

Holcomb has acknowledged dark tourism. They are the city where Truman Capote set his book In Cold Blood. If some of you are familiar with that, it's been a movie.

It's been the subject of many documentaries. And this was an actual homicide. It was Herb and Bonnie Clutter and their two children that were killed in their homes.

The murders happened because somebody was trying to rob. Them they thought that the Clutters had a lot of money. And yeah, it didn't pan out very well. And so the killers were put on trial and convicted. Now, the house still stands in Holcomb today.

The house is still there. It's privately owned. It's not open to the public. And yet people still visit.

Sometimes they'll knock on the door. But they've said that for the most part, it hasn't really been all that intrusive. But what Holcomb has managed to do is create a secondary site, a memorial park, a plaque that talks about the Clutters' contribution to the community. And they've been able to put information on the website because they realize people are not just going to go to Holcomb, Kansas to be tourists. They're not they're not finding a whole lot of other points of interest that they want to visit.

They're going to see the Clutter farmhouse. And so they wanted to acknowledge the Clutters. They wanted to do it respectfully.

So they talk about the Clutters. They talk about their contributions. They don't mention the killers. The Capote book talks extensively about the killers. But Holcomb does not. They don't want to give them any more publicity.

They want the Clutters to be remembered. And I think that, in my own research, I think that was a very respectful way to do that. Then you've got Amityville. They want nothing to do with the folklore behind them. Amityville started in 1974.

The whole story started in 1974 when five members of the DeFeo family were murdered in the middle of the night by the eldest son. The eldest son started to throw out all sorts of stories. And one of those stories was-- that, oh, I was possessed by demons. OK, so after the DeFeo stuff was all cleared out, they had left some of the furniture. The Lutz family moved in. And a month later, for whatever reason, they wanted to site, they moved out.

Well, they got in contact with the lawyer, wrote a book called, The Amityville Horror. Has anybody heard of The Amityville Horror? OK, so you know what I'm talking about. You know how fantastical some of those claims were, bleeding walls, marching bands going up and down the stairs that you can't see, the wife lifting up out of bed and floating away. I think I read this book when I was in sixth grade. And it was terrifying. But as you get older, you look at those stories, and you're like, yeah, no, there's not a pig person named Jodie up in the attic staring down at us.

So eventually, the book became a movie. Then it became a sequel. Then another sequal-- and these sequals are terrible, by the way. Don't even bother.

And then in 2005, it was a movie again. Every single time a new sequel, or a new documentary, or something new about Amityville comes out, people go to Amityville because they want to see the house, which is great for tourism in Amityville. But there's still people who knew the DeFeo's living in Amityville.

They knew these people. They were close to these people. They found that the people living in the house said nothing, literally nothing supernatural has taken place there. And they were living there for 35, 40 years.

So there you go. It's refuting the whole idea that this place is haunted. And yet still, people want to see it. The city has worked with the private homeowners. They've changed those infamous lunette windows to little square windows.

They change the house address to try to get people to not find it anymore. But people still know where it is. It's not that hard to find, even if they change the address. They have reports of people in the middle of the night coming and knocking on the door and wanting to come in and see it.

Yeah, I don't know about you guys, but that would irritate me after a while. So the local government was trying to work with these people. And in fact, I was talking with a friend of-- or I was emailing a friend of the daughter, the DeFeo daughter, who used to go over to the house and play with Alison DeFeo and go swimming in their pool and stuff. And she said, after the murders, a lot of people came.

And as teenagers, they would encounter these tourists in the community. And the tourists would ask, hey, where is such and such? And they would say, oh, go about two miles that way, and take a left and then down the road, miles from where the house actually is. They were deliberately steering tourists in the wrong direction because they just didn't want to deal with it. They don't like how ghoulish the story is. And so they have not acknowledged it. The local government has worked with the private homeowners, but has done nothing for tourism planning.

They don't want anything to do with the story. But it's not stopping people from going. People are still going. They're still making messes in the neighborhood. So this idea of acknowledging, embracing, and ignoring is just fascinating to me. And this is where my research lies.

I've got some study parameters at this phase in my research. The first one is I want domestic sites because it's easy to travel to. It's easier to get funds than international travel. And I wanted to be able to understand the local government context, meaning I understand local government.

I know how it works. I can talk to people about it in a reasonable way and understand the structure. So I'm keeping it domestic for now. Eventually, I'd like to go international. But that's just not in the cards at this time.

I wanted tragedies associated with a single community. There are a lot of tragedies and the worst of the worst, such as slavery, that impact regional, statewide. It's just too much to study for what I'm doing. So I'm really trying to keep it local. The point of interest, I needed that to be within a local government jurisdiction. A lot of tragedies, think the Keddie murders, that campground, the Charles Lindbergh baby.

Those things happened in unincorporated territory just outside local government jurisdiction. And so that would be a different governing body. And I'm a local government person. So we're keeping it with what I know. So that's just a personal preference.

I wanted cases of sustained public interest. A lot of these tragedies will happen. And people are really, really intense about it. And then something else happens. And the news fades away.

And the story becomes a footnote. I wanted to look at tragedies that have remained in the public eye. And so I've really kind of focused on things that are 30, 40, 50 years old by this time to see how cities are dealing with that long-term sustained interest. And then eventually, I'd like to move up to larger scale tragedies, like the regional, like the statewide, like things that happened beyond a single jurisdiction. But we got to work through the smaller parameters first.

And eventually, we can combine all of those into larger guidelines. Clear Lake and Salem are helping to build that body of knowledge. So my research goal and the things that I really want to focus on are the impact of dark tourism on urban planning and public administration. It's not being done.

But it's an important thing to do. There are other cities like Clear Lake who just haven't been able to sit down and factor how their dark tourism can be done in a good, respectful manner. So Clear Lake was selected as a case study. It was actually a roundabout way. Somebody said, hey, I was in Clear Lake lately. And I'm like, oh, that might make a good study.

So I started looking into it. And I'm like, this fits all of the boxes. And then I contacted City Administrator Flory, and he's like, come on down. We'll hang out. And so we were able to take a look at that case.

And it's been probably one of the shining examples of dark tourism planning. So a little background on Clear Lake. This is a great community. It's about 7,597 people. Probably give or take a few because that's a 2019 number. It's been a hub for arts and recreation basically since its beginning.

They had a bandshell. And there were people coming in from all over the place in the 1800s. This place has grown quite a bit. And even before the crash, people were visiting Clear Lake for its arts and entertainment. It's been a very welcoming community.

The lake, just beautiful. If you ever get a chance to hang out there, I highly recommend it. Now, Clear Lake and Mason City, which is very close to it, a population of about 27,000, give or take a few, they have contributed greatly to the tourism economy of Iowa.

Now, Iowa itself, prior to the pandemic-- well, we know nationally that tourism is a billion multiple billion revenue industry. It's widespread. It touches all corners of the country. The pandemic took a hit of about $415 billion. We don't know how it's going to recover after that. Hopefully, it will recover, and things will be back on track.

But nobody can say when or how much it's going to recover afterwards. Now, Iowa tourism reports that consumers have spent about $9 billion on tourism in Iowa. Pretty substantial economy. So next time you get annoyed that there are tourists in the nightclubs that you're going to or that they're taking up your tables in the restaurants, just remember, this is good money for your community, that this is something that you want to have happen. So welcome them.

And make them feel happy about being there. Cerro Gordo County-- is that the right way to say that? Because I've only seen it written, really. Cerro Gordo County, which includes Clear Lake and Mason City, has contributed $3.68 million

to Iowa's tourism economy. That's a pretty substantial amount. These are cities that are smaller than Minneapolis. And this is a very healthy economy.

As you can see here, in the Bureau of Labor statistics' data, Cerro Gordo County, including Clear Lake and Mason City, is amongst the top tourism industry leaders. Now, the tourism in Iowa, in general, just everybody together, it travels generated enough state and local sales tax to pay salaries for firefighters, police officers, sheriffs. Now, when you can take that sort of fundage and provide public safety, you're doing all right. Again, we'll see how the pandemic has impacted that. Now, we're going to shift gears a little bit.

We've laid down the foundation of Clear Lake, dark tourism. But now I want to talk about 1959. 1959 was quite a year. Rock and roll was this newer genre of music. And it was really resonating with the teenagers and the young adults. It was starting to gain popularity.

And so these record producers were determined to get that genre's spreaded. They were determined to get their names out. All these talented musicians coming up, Elvis, let's see, Bill Haley and the Comets, and of course, the people who went on the Winter Dance Party tour, they were all part of that phenomenon. There were tours all over the place. But the one that we're specifically talking about in 1959 is the Winter Dance Party. This was a great tour.

They had 24 stops. They were going to go to these ballrooms all over the Midwest in the middle of February. And they had headliners, Frankie Sardo, Dionne. These were up and coming people. And then they had the headliner, Buddy Holly, Charles P. Hardin and Holley.

He had hits like Rave on, Maybe Baby, Oh, Boy. I was listening to some of them on the way down. And they're just good songs. You heard some of them as you were walking in today.

So thank you, Elise, for arranging all that. So Buddy Holly has had such a musical influence that you may not have even known. Paul McCartney and John Lennon often cited Buddy Holly as one of their strongest musical influences. They said that if he can write music, we can write music.

They even named the Beatles after Holly's band, The Crickets. Not directly, but the whole idea of this bug, adding a sort of musical connotation to it. Bob Dylan actually went to the Winter Dance Party concert in Duluth. And he was hugely influenced by the music of Buddy Holly. So the influence actually is sustained. We still see musicians citing Buddy Holly as one of their early influences.

And if you listen to his music, you can tell why. We had Ritchie Valens, 17-year-old kid. He was up and coming as well.

He had had three hits in a career that probably spanned maybe a year. They were expecting great things of him, so they sent him on this Winter Dance Party. His hits included things like Donna, Come On, Let's Go. And of course, you probably heard the song, La Bamba. That's still played quite a bit and covered by numerous bands. He was one of the first Mexican-Americans to really fuse this rock and roll sound with the traditional Latino sounds.

La Bamba is a nod to that. And if you listen to some of his other stuff-- and there's one that I can't pronounce, but it's a great song. It's a musical track that takes a traditional Mexican song and puts it to a rock and roll beat. And it is so good. He was a prodigy. He knew how to play.

And he was great. Now, The Big Bopper was known mostly as a novelty act. He did things like the Purple People Eater Meets the Witch Doctor, the Big Bopper's Wedding, Little Red Riding Hood, and of course, his biggest hit, Chantilly Lace. But how many of you knew that he's credited for pioneering music videos? He's actually one of the first to use the words, music video in an interview in the 1950s. I didn't know that before I started researching that.

So his impact was, yeah, on stage, but actually, behind the scenes quite a bit. He was producing videos for television in 1959. And that's years before a lot of people started thinking about that.

So those acts, they all got together on this tour bus and went all across the country. Well, I guess I should say all across the Midwest. It was not a good time for them. This was actually hell on Earth for them. They had 24 stops.

Great. But did they mention that there were no rest dates in between? They had a concert every night for those 24 nights. There was one night open February 2. That's the night that the tour manager said, hey, we got this free night. You guys don't really need to do laundry or rest, do you? Let's book the surf in Clear Lake. So they ended up bouncing.

I think at one point, they went from Duluth to Fort Wayne. They went from upper Minnesota, to Wisconsin, to Iowa, then back up to Minnesota. They were bouncing. There was no coherent plan to this tour. But the best part, the temperatures, 20 degrees down to 36 below. That is not fun.

If you've ever driven in winter conditions in Minnesota, and I'm assuming most of you have, you know how much fun that isn't. But the best part about that? The heater on the bus wasn't working. And they had to drive four or five hour stretches with no heater. Eventually, the drummer for Buddy Holly ended up getting frostbitten feet.

So he was hospitalized for some of this. And so the guys would take turns filling in for each other. So the bus is breaking down. The bus' heater isn't working. The drummer is out of commission completely. They have no rest dates.

Oh. I almost forgot the best part. There was a flu going around too. So most of the musicians are laid up with the flu. They're still on this bus.

They don't get to sleep. They don't get to do laundry. They don't hardly have time to do anything.

But they're playing these concerts. And they're doing a great job. OK. There we go. One of the stops-- some of you probably know this-- is a local stop, the Kato Ballroom.

And Dean Loayza actually had a wonderful idea of having this session down there. Logistically, we wanted to have all the AV equipment. But that would have been really fun. That stage is amazing. They played in the Kato Ballroom on January 25 just a few days before they played the Surf.

And so if you go down there, you can see some pictures from that concert. Somebody managed to get a picture of Buddy Holly hidden behind a microphone, unfortunately. But there is a local connection. So if you go down to the Kato, you see the stage where they performed, which is always a chilling experience. So it was not a fun tour.

It was difficult. It was cold. People were literally freezing their toes off. This was not a good time. Buddy Holly said, OK, I know we have this five-hour drive up to Moorhead after we play Clear Lake, Iowa. I'm exhausted, guys. I'm going to hire a plane.

I'm going to take some of my band members. Tommy Allsup and Waylon Jennings, you're coming with me. We're all going to pay $36 to take this plane from Clear Lake to Moorhead.

Well, that's great. The Big Bopper wasn't having it though. He wasn't feeling good. He had the flu.

So he convinced Waylon Jennings to give him a seat. Waylon Jennings, being a nice guy, gave him the seat. Ritchie Valens, who already was not that fond of flying for personal reasons, he did a coin toss with Tommy Allsup. And Ritchie Valens came out going on this plane.

So they each paid their $36. Carol Anderson drives them to the airport. Everybody gets on this plane. And when Buddy Holly found out that Waylon Jennings gave up his spot, he looked at The Big Bopper and said-- oh, I'm sorry.

He looked at Buddy Holly and said, Buddy, I hope your old bus crashes. I'm sorry. I hope your old bus breaks down. And Waylon Jennings says back to Buddy Holly, well, I hope your old plane crashes.

He said, by god, for years, I thought I caused it. He had to live with that for the rest of his life. And I know I mangled the telling of that story.

But the point is Waylon Jennings was really affected by that for the rest of his career. They got on the plane shortly after midnight. They took off from the Mason City Airport. And about six miles out, they crashed into a cornfield. It was found the next morning when they didn't report to Moorhead, Minnesota.

They were piloted by 21-year-old Roger Peterson, who was not instrument rated. He had flying experience, but not in the snowy unclear conditions that were in place on February 2. So the deaths of these musicians ended up impacting teenagers. It impacted a lot of people.

This was, for a lot of teenagers, the first time they had really experienced a death like that. They were young people. Not all of them had experienced something like that.

So you got the three musicians. Roger Peterson is in the upper right hand corner. So young guys at the height of their careers just cut short. Nobody really knows when tourism started in Clear Lake.

It could have been the day after the crash. It could have been months afterwards. We do know that acknowledged and understood tourism started in about the 1970s when the Mad Hatter-- I'm blanking on his name. Do you remember what his-- - Darryl. - Darryl "The Mad Hatter" Hanson? - Yeah.

I looked it up. And I can't remember. - Yeah. I've got it written down. But The Mad Hatter started this Winter Dance Party in honor of the musicians.

And it's something that's been a recurring event every year. And it's still going on. You can go next year to the Winter Dance Party. And I guess, it's a really good time. I have yet to go.

I got to convince somebody to take me there, so we can go dancing and stuff. It takes place at the Surf, which is the last venue that the musicians played at. The Surf Ballroom, this venue that they played at, has been very well preserved. It's been so well preserved that it's on the National Register of Historic Places and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

It has made it, not just for the architectural aspect, which was really well done, but also because of its association with that night. That night propelled Clear Lake into the pantheon of dark tourism. So the Surf Ballroom and its preservation makes it a primary site. People come from all over the world.

They got a lot of people from England because over in England-- that connection to The Beatles meant that people are fascinated with Buddy Holly. And they want to come to Clear Lake. And they want to see the Surf Ballroom. They want to come to the Winter Dance Party. So the Surf Ballroom acknowledges this.

They provide a little museum space, so people can see relics from Buddy Holly, JP Richardson, and Ritchie Valens. They've accommodated the tourism. The crash site itself is set up for tourism as well. This is a privately owned land. This is a cornfield that's still owned by a farmer.

He still farms that area. But they've cleared out a path and accommodates people who want to see where it happened. And they can leave little memorial trinkets. They can leave things that honor the musicians.

You can see that they've got three records and a metal guitar. They have a little memorial for Roger Peterson, the pilot, as well. To mark off that trail, they've got a pair of Buddy Holly's signature glasses. So they have acknowledged this as another primary site.

So Clear Lake has two primary sites. One of them's privately owned. One of them's owned by-- or owned and operated by a nonprofit. The city does not own either of these lands. And they don't have zoning specifically for dark tourism. But the city has been very involved in dark tourism planning.

One of the things they did was took the site of an old gas station, an Amoco, remediated it, turned it into Three Stars Plaza. Now, this is a Memorial site that is not directly related to the musicians. They weren't there, that we know of. But they've created this site just a little bit a ways from The Surf. You can see the ballroom of The Surf right over here.

And the Three Stars Plaza is basically a record spindle with three records looking like they're going to drop down. The records have the names of the musicians. And they explain a little bit about the musicians in some memorial plaques. You can press a button, listen to the music, and learn about their lives. So they provided a secondary site. Now, what this does, it gets people out of The Surf, a little into the community, gives people a starting point to start exploring Clear Lake.

So a secondary site provided and maintained by the city plan for-- it was built in 2010, finalized in 2011. The artwork was installed in 2011. The artwork actually came from private donations from Steven and Vicki Succop. Is that how you pronounce it? And they did not solicit the Valens family for money for this. But the Valens family was so-- they found it respectful.

They really connected with it, so they donated about $3,000 to help create this memorial to their son. So Clear Lake is doing something right there. The level of local government support from Clear Lake has been astounding. Salem does the same level. They have embraced and taken this dark event that could have been buried under the sand.

The Surf's an older building that could have been torn down ages ago. But instead, they've used it as an educational springboard. So what can other dark tourism cities learn from Clear Lake? I'd say they can learn a lot. And this is what cities like Amityville and other cities who don't really know how to do these things respectfully or maybe choose not to do them at all, they can learn a lot from how Clear Lake has handled this case. First and foremost, work with the families. If there are still family members alive, if there are still loved ones involved, contact them.

Work with them. Find out what they need. How can we honor this person that wasn't just a teen idol for you, but somebody that you loved, your son, your brother, your friend? They've been in contact with the Valens family, with the Richardson family, the Holly family. Those families have attended Winter Dance Party events. And in fact, the Valens family often host a brunch for people coming to the Winter Dance Party. And if I remember correctly, the Valens family actually moved to the area.

They didn't really have a connection to Iowa prior to this. But apparently, Clear Lake is doing something so right, that the Valens family has decided to contribute continuously. So that that's actually pretty impressive. You wouldn't hear about that too often. The Holly family doesn't have quite the level of involvement. But JP Richardson's son used to be very heavily involved in Winter Dance Party events too.

There is a caveat there. You're not going to be able to please everybody. You're not going to be able to listen to every voice. Unfortunately, you get cases where there are so many people who died in the incident, or the incident was so long ago that there's nobody alive, that there's no way you can incorporate those voices into memorial planning. And I take a look at the 9/11 case.

September 11, about 3,000 people

2022-11-24 21:06