2021 Distinguished Lecture Helen Nissenbaum Contextual Integrity

all right um thank you everybody for coming i think we'll go ahead and get started even though some folks might be popping in um at the last minute so my name is julie kientz i'm professor and chair of the department of human centered design and engineering at the university of washington and i'm honored to welcome you to our 2021 distinguished speaker event and thank our guest professor helen nissenbaum for joining us i want to first start out by acknowledging the coast salish peoples of this land on which we are working today the land which touches the shared waters of all tribes and bands within the suquamish, tulalip and muckleshoot nations we respectfully acknowledge their stewardship of this land throughout the generations during this year of upheaval it continues to be my top priority as department chair to sustain our close-knit community in hcde and across our field guest lecturers are an important opportunity for a community to come together in shared learning the hcde distinguished speaker series was created in order to provide a community event where students staff faculty alumni and friends could gather together to hear talks by people that have been innovating on bold — innovating boldly and thinking deeply about topics that have profound impact on human centered design and engineering the distinguished speaker series would not be possible without the generous support of members from our community i want to first thank former hcde chair judy ramey and friend of the department stephanie rosenbaum for sponsoring the lecture series in hcde since 2009 we are honored to continue their legacy i'd also like to recognize our friend jing de jong chen whose endowment aims to broaden understanding of human centered design issues in cyber security and privacy thanks to her investment we were able to have dr nissenbaum with us today finally i want to thank our hcde staff especially zoe bartholomew leah pistorius and stacia green and the research committee in hcde spearheaded by associate professor charlotte lee for their efforts in organizing this event today i'm now going to hand things over to professor and associate chair beth kolko to introduce our distinguished speaker dr helen nissenbaum thanks julie so i would like to thank all of you for attending today and uh thank you to dr helen nissenbaum for being with us today i am especially excited to welcome dr nissenbaum she and i met many years ago at a symposium that was a pivotal moment in my intellectual life for many reasons uh mostly because of my conversations with helen if i may call you helen so i'm gonna set the scene for those of you in the audience it was uh 1995. it might actually have been 1996. neither helen nor i can remember and i couldn't find any online record of the event i tried but it was a symposium about the internet it was in jackson hole wyoming and helen i and john perry barlow were keynote speakers for the event so one of the things that i remember most from the event was giving my talk and then sitting in a cafe at the venue it was closed but somehow helen and i had managed to secure ourselves some coffee and she's sitting across the table from me and she says your work is fascinating but what is your field and from there we launched into a conversation about the need for interdisciplinarity in order to make sense of increasingly ubiquitous online systems uh helen doesn't know this but that conversation emboldened me in my own work and helped encourage me to move from the humanities to engineering just a few years later in 1995 or six in the late 90s let's say the internet was just emerging from being a text-based medium and this was against a backdrop where anonymity online was considered largely a positive development the online world had plenty of trolls back then but we didn't have bots helen was at the forefront even then one of the only scholars asserting that questions of trust and privacy and their interplay would be key factors in how emerging technologies would come to shape interactions and institutions i want to take a moment and recognize her prescience 25 years ago in identifying what would be fundamental challenges to growing technological infrastructures so she is here today to speak on her work regarding contextual integrity research which builds on her continued outstanding intellectual contributions and that continues to provide bold and insightful guidance on how we can all think more critically and practice more carefully the work around technology design so it's my pleasure to introduce helen to you all today she is a professor at cornell tech in the in the information science department as well at cornell university she is also director of the digital life initiative which was launched in 2017 at cornell tech to explore societal perspectives surrounding the development and application of digital technology focusing on ethics policy politics and quality of life helen's research takes an ethical perspective on policy law science and engineering related to information technology computing digital media and data science her research has delved into issues of privacy trust accountability security and values in technology design her books include obfuscation a user's guide for privacy and protest with vin brunton and privacy and context technology policy and the integrity of social life the title of our talk today is contextual integrity breaking the grip of public private distinction for meaningful privacy if any of you have questions during the talk or the q & a portion please submit your questions by clicking the q & a button that should be at the bottom of your zoom window and with that please join me in welcoming helen all right so thank you so much beth i have to say it was like what they call a blast from the past when i i got your email to invite me to give this lecture and it was just so wonderful you know just to go back to that crazy time and try and trace a trajectory now i don't know that i certainly didn't feel prescient in any way i just knew that these were such fascinating questions and i didn't think that a philosopher could solve them without so many other people in different disciplines so here we are and let me do the share screen thing oh so it popped on nicely just like that all right um i am grateful and excited to be here is an amazing group of people for me to be presenting my work to because i feel like you're in the trenches with me and hopefully some of what i say will be will will connect with what you do and some thoughts that you have and i also want to say that i'm i was so excited to be here that i might have stuffed just a little bit too much into my talk so don't think i'm crazy if you leave this talk with just some of the things i've said staying in your brain i'll be happy and of course i would be delighted to share more and and carry on the conversation and so here goes i'm also happy that um you were interested in hearing me talk about privacy because i have to say that you know there's always like a shiny object in our field and now there's so much attention to ai and ethics which is it warrants that attention but what what i what i fear is that we don't the by turning away from issues of privacy we failed to understand or we failed to realize how important getting things right or even getting things better with respect to privacy is so intricately connected to some of these important questions of ai and ethics so i'm happy to go there if need be let me see oh sorry okay so here's here's the talk overview i want to talk a little bit about why contextual integrity really like why privacy what what gripped me about privacy what is contextual integrity and how does it differ from other ways of thinking about privacy some applications and some potential challenges there are many people and i'm not even sure that i've listed everybody but there are many people along the way who've helped develop contextual integrity with me both the theoretical aspects of it and also showing that contextual integrity the framework of it could be applied in design and in formal languages and also could be adapted to empirical social science research and so forth so led me along different pathways now back now to the talk the talk outline why why privacy why contextual integrity and um this is a slide that i use often when i'm talking about privacy because i wanted a lot i like to mention that i didn't though i have a phd in philosophy i didn't approach the issue of privacy to say oh privacy it's such a rich concept and um i'm i'm an ethicist or a political philosopher and now i need to understand privacy from a philosophical and of course a legal perspective it was more looking at this range of technologies some you know that we already were aware of at the time that beth and i were were meeting so many years ago and now as i use this slide i'm constantly oh sorry i see a typo forgive me i'm constantly updating obviously without thinking too much about it i should have applied my my spell checker but anyway um obviously updating all the time but the important thing for me to reckon with is is when people observe what's done with these technologies and of course whenever i say technology please just know that what i mean is socio-technical systems because it's never you know the bare technology as if it could be functioning on mars so what is it when people see some of the applications of these technologies and they complain they cry out that privacy has been violated and i wanted to show you that this is a very curious thing that i came across um etc discovery and invention have made it possible for the government by means far more effective than stretching upon the rack to obtain disclosure in court of what is whispered in the closet the progress of science in furnishing the government with means of espionage is not likely to stop with wiretapping ways may sometimes be developed by which government without removing papers from secret drawers can reproduce them in court and by which it will be enabled to expose a jury the most intimate occurrences of the home advances in the psychic i mean that might give things away and related sciences may bring means of exploring unexpressed beliefs thoughts and emotions so this was um written in 1928 by brandeis and many of you in the famous olmsted v united states where this was a dissenting opinion which then was overturned 50 years later but just to show that this the idea of technology threatening privacy in these ways isn't something brand new to us so we hear people claim privacy is violated and it was fascinating to me to say well why are people angry what are they afraid of why do we think that these actions are morally wrong and i and that led me to to this quest for what i like to call a meaningful account of privacy and um i mean by that the philosopher's task to begin with of defining a concept that's clear and rigorous but also more the social scientists concept to find one that's true to us that it's makes sense that it responds that most of the time when people say oh my privacy is being violated this account actually captures that and we also want a value that's ethically legitimate so that we can claim that when someone's privacy has been let's say threatened or reduced or placed at risk there's something wrong with that and we need to do something about it and it's worth defending with technology and policy so that's what we are after and in in particular the the events that really shaped my interest and this is really responding i wanted to have a theme around which to discuss contextual integrity because really the goal of this talk today is to present contextual integrity as an answer to these challenges that a response to to the quest for a meaningful conception of privacy but largest marketplace households as you can see and i hope you've been reading was i have to say by today's standards was was child's play but what was important about it was when lotus and equifax are eventually under a lot of pressure decided to withdraw the product they said we weren't doing anything wrong because we were simply using data that came from public sources and therefore we weren't violating privacy and much later when people started worrying about google maps street view the defensive initially when google didn't want to do anything about anything now it's like blurring faces and and so forth their argument again was we have every right to drive around on the roads and capture information capture images from public spaces no privacy issues are raised because these are public places this seemed wrong and many people weren't buying of course we were already in that phase that it was you know tough luck law doesn't help you any and um these arguments held sway so what is contextual integrity and how does it address these issues what these cases do and many of the cases that i bring to bear in order to showcase contextual integrity and how it differs i think of it as a prism i run these cases and then we see how the different theories respond to these cases so for example we might think about facial recognition systems in public used in public places do they violate privacy in this i know you know major discussions going on ban the scan in different cities um happening in new york and potentially in other places um you know and here's facial recognition as a as augmented reality in classes and so how do we think about this using contextual integrity and they're going to be a lot more examples as we move along so what this is a whirlwind pass through contextual integrity and i want to present it to you in a modular way so the four key ideas that i've identified and i'm i'm going to introduce them progressively and i have to say that at times when i present these four key ideas people will say oh helen you know i really agree with the first one but no then you then you you've lost me but but it's okay you know i i want to show how they build on each other and um we can see the various inter interdependencies i'm prepared to uh defend all of those key ideas but um this is a discussion for us to have so what's the first key idea the first key idea oh sorry i i forgot i had this slide what uh sorry that like really break br broke the drama but what we have the way i'm going to present it so that we see this prison prism effect is i'll describe what the key idea is and then i'll contrast it here's what it is here is how it's different so the first key idea is that privacy is about appropriate flow of information just that that basic idea which may seem uh nothing to it on the other hand it really contrasts with a million computer science papers where privacy is presented as secrecy and any data that may leak that you often see this notion of leakage because it's not it's like a non-moral concept is considered a violation of privacy so privacy in this case is secrecy and leakage is a violation and the in in privacy by design there's this concept of minimization and it's basically says um any reduction of the amount of amount of information like data minimization is considered to be um giving people more more privacy now that's the first key idea privacy is appropriate flow so when people say oh privacy it's such a complicated concept no wonder we're having such trouble i say calm down it's very simple privacy is appropriate flow of information and then they say what do you mean by appropriate flow and the answer that i give is that it conforms with norms or rules it meets people's expectations and the number four key idea so you'll see in a little moment why i'm doing um i have i can count but this is just you know um how i'm laying it out at the moment is that in fact it's legitimate norms or rules worth defending they're morally justifiable and i say norms or rules because again i'm talking to computer science colleagues they really don't like the word norms unlike the humanists and the social scientists and so we talk about rules instead but now let's just focus on the key idea number two this is where context come into play first so what we really mean to spell it out is that flow conforms with contextual informational norms or rules so appropriate flow meets expectations so we connect up here with some of the legal concepts of a reasonable expectation of privacy now there's a social theory that underlies this second idea and that is that social sphere social social we live in a social life that isn't an undifferentiated social space but rather we have these differentiated social spheres and here i don't invent the idea but rather i'm drawing on ideas that i read about from social philosophy and um theoretical social sciences um and i'm now giving you the basic ideas behind what characterizes context importantly they're characterized by purposes goals and values they're characterized by distinctive ontologies of roles or capacities in which people act certain practices and and just it's nothing magical but when we think about healthcare education family these are all contexts and then we have norms and the norms govern how people behave in these contexts and among the norms are informational norms which are could be implicit could be explicit and these are the norms or the rules that govern the flow of information in a particular context and the claim is that we live we we have a we know if just by living in society we know a lot about when data or information flows conform with the norms now number three this is where the third key idea comes in so maybe you agree with me so far you say you know the law also agrees with me if we want to find out if privacy has been violated we have to show that people's reasonable expectation of privacy have not been met and that's a signal that privacy has been has been violated adding to that contextual integrity proposes that these rules have a certain structure this is really important to the big argument and i've learned from my computer science colleagues this is the ci tuple the five parameters five not five um and they are actors informat subject center recipient information type and transmission principle so um and when we talk about actors remember we're there's always this contextual ontology of actors it's people acting in certain capacities the norms govern flow in terms of there's a meaning when when we're talking when we're mapping these flows and we characterize the flows in meaningful terms we have information type specific things age gender books you've read so forth so on and hopefully you've been reading a long while because i'm not going to read everything in the slide and then there's this parameter called transmission principle and this is uh the other parameters are known in a lot of the role-based approaches to privacy but this transmission principle um we always understood it to be there i think it's quite intuitive but this theory makes it explicit which is it's the terms under which the information flows the constraints under which the information flows so in the very common thought of privacy sorry of you're providing information with consent cons with consent is a transmission principle because that is the constraint under which information flows but it doesn't always require consent so when you're filing your income tax returns it's not that you're consenting to provide the information you're being coerced you've been compelled that's a law it requires that you provide and of course information can be bought and sold it can be a one-way flow it can be reciprocal so the physician gets to hear what your health complaints are but you don't get to hear what the physician's health complaints are and so forth so there's certain um and then one important one is with a warrant so it's really important in the law we see this over and over again with the fourth amendment did the police have to get a warrant in a certain instance of search and if they didn't get the information with a warrant then we say well it was unlawfully gained so that happened so this concept of transmission principle really covers a lot that's very familiar to us but it then it identifies it now have this question mark near use because over the years i've had lots of debates with people as to whether i forgot i should have had six parameters and the sixth parameter should have been used and maybe maybe those people are right however there are ways in which the use parameter and and i don't know if i'm gonna have time to go go into it the reasons for hope for believing that the use parameter which may not have been important at the time have become increasingly important as we have as we've entered this these times that we're living in but but i'm just going to leave this up in there so here's you know you know how it is you learn the mathematical concepts and then you learn here are the concrete instances but here are some um rules that fit the structure where we you know travelers are obliged are obliged upon request to show the contents of their luggage to the csa agent to show how this this well-formed sentence would mention different parameters and i want to show you how some of our sectoral laws so this comes from hipaa when they write the rule they actually do use these parameters which which which was i wouldn't say proof but it was very heartening because it suggests that these parameters capture something intuitive in how people want to think about and evaluate data flows and this one is i always use this one i like it a lot because it goes against the common wisdom that you always need the data subject's permission to share information and in this case what we're saying is that actually it's only with authorization um with the from the psychiatrist that this information can flow and um this work by the way comes from a paper uh with from from these guys they developed formal language and very excited you know maybe we can use this formal language to implement or enforce in a computer system okay so here we are um i promised that i would show you the connection um between the key ideas and other approaches or other ways of thinking about privacy and here i i wanted to just raise this little flag and say this particular way of thinking about privacy which is conforms with contextual informational norms and the norms having the structure is different from two dominant ways of thinking about privacy one we are one is that privacy protects only the private so we we're we're very much dominated by this dichotomy of private and public and privacy only applies to the private and another dominant definition which comes from alan weston privacy is control over personal information how many articles countless countless countless even progressive thinkers on privacy end the article i'm thinking about you know the new york times had a recent series on privacy what we need is to give people control over information about ourselves please one thing to take away this kills privacy this this is the death of privacy and we really need to have a revolution and we're going to have a revolution everybody and it is to reject this definition of privacy as controller with personal information so this idea we back now to the google map street view privacy only applies to the private in the case of the public all bets are off so that so and contextual integrity says no we don't divide the world into two things we don't say public information private information we have a much more richer understanding of this informational and spatial ontology that comes from social domains we cannot build privacy on top of this private public dichotomy it doesn't match up and then when we want to think about why privacy is control over personal information has led us has gra has resulted in us being beached when it comes to privacy and i should say that it stems from what was initially a great idea code of fair information practices but ultimately builds on this idea that the right to privacy is the right to control fast forward to the present and i'm not going to spend too much time i'm whipping through these you know this is what this is where we get to when when we have the operationalization of privacy is control we have these privacy policies and you know have a whole nother talk about privacy's control and privacy policies but i just want to bring to attention something we all know very well and the conclusion of this quick little foray so now we have a first approximation of a definition of contextual integrity contextual integrity is preserved when information flows conform with entrenched informational norms and it is there's an assumption of of what these norms are now like any norms they're contested they can't sometimes controversial uh they're not 100 held and so on but but here's the first approximation and the point how this connects with technology remember the whole list of technologies that i presented at the beginning is that these technologies raise flags and make people crazy because what they're doing is they're disrupting the information flows and when i say disrupting the information flows if you're a privacy as control person the only disruption that is worth mentioning is whether this flow happens without someone consenting but when you're when you hold contextual integrity as your framework for privacy then what you mean is that you can capture the disruption by some alteration in the data in the values for the parameters that come about when you introduce certain kinds of technologies so when we go back to our facial recognition technology the public if it's in public you know you have oh you have these fourth amendment plainview doctrine that says you know if it's in plain view then no holds barred i'm just obviously there's a lot more detail when you are privacy as control then if you choose to share the information and choose is like you you arrive at you know a website whatever it is and you are implicitly agreeing then the third then it's like well you've agreed to share this information under these in these terms and that party can do whatever it likes as long as it doesn't violate the terms of the privacy policy but what privacy is contextual integrity says and i'll be you know fairly specific about it is that first of all when you're walking around in public so we're looking at the hardest case facial recognition in a public space there's certain even if you accept that there's certain information that can be captured traditionally or what the expectation is your name is not known your identity is not and now with facial recognition we have a novel flow we have a disruptive flow suddenly the information type changes because now your name flows and second of all because of the technology it's not just like you know i see someone across the street but rather the image can be captured and it can flow to all sorts of places and so it's not the case oh public is public anything goes this really constitutes a change and privacy is contextual integrity gives you a finer grain way of revealing what the changes are when um when i talk say with students about surveillance technology like drones and and cameras what i said to them is please don't get all worked up about these technologies because you want to understand that these technologies can be designed in different ways and you as a technology designer can decide are you going to store the data is the data real time who gets access to the data how fine grain is it does it feed into a facial you know so many different questions that are relevant to whether to what the privacy dimensions are of these systems it really belittles it it doesn't give enough attention to the importance of what's relevant in these systems by just waving your hand and attacking the systems whole cloth but it really requires a design approach here's another experience that we had in the past few years just to give you a little bit of a heads up the voter role information and voter registration information it's a state by state decision and many states for many most states in fact voter role which is whether you voted in an election is public and yet when this commission on voter fraud requested the information from states the states said no even though this information was public so the argument of public is public no holds barred is belied and i think people a hazard a guess that most people were very relieved at this resistance so all the parameters matter and it doesn't serve us to overlook some of the parameters now i wanted to let's see how am i doing on time we started all right gosh i'm going to try and whip through this um because what i th this was the promise i made to you guys i i wanted to show how th this is now my collaboration with people who do empirical work empirical survey study in particular kirsten martin and what we want to do show is that when you pay attention to all the parameters you can disambiguate a lot of bad survey stuff that has been going on for decades so we did we looked at the private public distinction and we looked first at sensitive data and then we looked at what's so-called public data so the first article was showing confounding variables with sensitive data and i just have a couple of slides for each of these studies what we first did is we looked at the information types found to be most sensitive by the pew foundation now according to the public private dichotomy it we would say that you should really protect the most private and depending on your theory of privacy maybe secrecy we hold these to be secret when you add and it feels so obvious you know when when i show you these results when you include the additional parameters into your story you see that even the most sensitive data health information when it goes to a doctor no problem obviously when it goes to um the the most unpopular one was always the data broker then we're very upset about it so it's got not you can't take the information and divide it into two categories and then know how to treat it then we showed the opposite we wanted to show that even information in public databases people felt that there were privacy interests and i should mention that early days i had written an article my first article on privacy was like oh revealing that there's privacy in public again each time we use this factorial vignette survey approach and we ask the question is it okay we spent so much time asked figuring out how to ask the question we we were trying to get at the norm we didn't want to get the preference so i'm sure that anyone who's been doing this kind of survey stuff knows like how you ask the question and there's such fine-grained distinctions we ask is it okay and what i wanted to point out is how um let me see what i can do here okay so in the first case we're saying a company receiving job information by information type um how okay is it to receive criminal data from a data broker from a from government website and from the subject him or herself and you can see the discrepancies uh the one we kind of enjoyed a lot was we imagine you know you're going to someone's party and you decide oh that's a big house i wonder how much they paid so you know you look up online you go to you know one what what are those data broke what are the what are they called when you look up and you see what's something or redfin those companies yeah yeah yeah so not not nice not appropriate but if you ask the person what you paid that's it's okay it's not a hundred but it's it's much much better and so forth so really these factors affect you know where going from negative to positive when you start adjusting the different parameters and then finally we looked about we we looked this was a much more complex complicated paper it's just just come out privacy interest in public locations and i mean location tracking is is in it's huge i'm sure you guys are aware of this you know this is the plane for you doctrine we we did multiple rounds of this survey and um i'm just letting you look at it for you know 10 seconds and um what what we show i mean this is just a little fraction i just mainly wanted to point out that when what's important by the way is that it's not only who gets it by what means which we used as a proxy for a transmission principle but we also especially kirsten was interested in what happens when the location data allows you to draw certain inferences and i was particularly interested in the place versus the gps latitude longitude the kind of semantics of the location so you can see here's the fbi collecting look at this kind of location uh but when you look at the data aggregator everyone hates that so these location aggregators that are out there that are what are they called you know data location data brokers and the tons of them that you know it's been discussed a lot uh people really think it's unacceptable but sometimes it's okay for the fbi but anyway you can draw conclusions and the fascinating thing was when we were doing our pilots we find people don't really distinguish the precision so gps latitude longitude and if you which is what you can see street city they're very close but what did matter is location versus place when you give semantics to it that really causes different responses okay so i've done all this and i'm probably some of you are saying you know tyranny of the convention the whole point of technology is to disrupt data flows and sometimes it's for the good so isn't this a terrible theory that it always says that disruption is bad so now we come to the fourth key idea which is that it's not only that appropriate flow requires legitimacy the norm needs to be legitimate we want to allow for technologies that come in and make things better and we also have to allow for the possibility that technologies can disrupt flow look bad at the beginning and then over time make an argument that in fact these technologies are not violating privacy and so the theory has a way of evaluating these novel flows it's a layered approach and i'm going to be very i'm not i'm not even going to spend time except to read the slide we evaluate the differential impact on the affected parties or stakeholders which is for individual custom benefits we evaluate them in terms of ethics and political principles so this fabulous literature on you know how inadequate privacy can chill speech and freedom and autonomy and so on and then the one that's the new contribution of this theory is contextual functions purposes and values and i wanted to show you that around this time andrew mellon proposed that irs records that tax records go from being public to being private and why did he say he didn't say because it hurts people that embarrasses them et cetera et cetera his argument is it will mean that people will answer their tax returns honestly and the treasury will get a lot of money so his argument was a societal contextual argument here's some ideas about purposes and values uh that the different and and this is just me you know spinning it i feel like each of everything i've said you know take education there's a there's an argument to be had about what the ends and purposes and and and values are for educational context and so now i want to come back to the definition no longer a first approximation and the definition is contextual integrity is preserved when information flows conform with legitimate informational norms and there's work to be done to transition between entrenched and the point is that sometimes we don't have entrenched norms and we need a way to evaluate flows so you know with cambridge analytic it was like oh people didn't give permission and i'm thinking who cares what we care about is that it undermine democracy that's what we need to care about um and i am going to uh maybe i'll ask i don't know julie how am i doing how many minutes can i have more uh depends on how many questions you want to be able to answer we do have about six questions that people have asked so far but um sure five minutes sounds great okay okay great because that's i think i think yes so um i'm not going to go into this article this was an early article there was a debate going on in various states about posting court records online there too the argument was court records they're public records what difference does it make if it's a file in a draw in a courthouse or a click away on a website now any of us sitting here know how enormous that difference is but once again it was like public is public what does the medium matter and this article carefully shows how when you change to a different medium you affect the values of the parameters and then again we ask the question when you change the flows what values are you promoting what harms are you bringing on board by making a very thoughtless change in the medium without going through this analysis and finally we'll come back you know to our this case we've been looking at and again we show there's a disruption that's really important and then we discuss we when we evaluate the disruption first we have to show it using a more fine-grained measurement which is the five you know the ci tuple we then have to discuss and of course many of the argument arguments are just to give throw one off the cuff you know people won't go um and protest because maybe they're afraid undermines democratic values and this one this is the last one thanks to badger friedman i don't know if she's here today but she a few days ago sent me this example of the ancient like hundreds of years old letters that were folded in a way that if you would unfold them it would break them and so there was the application of x-ray technology to be able to unfold without damaging the artifact and actually read the words of the letter and you might say to yourself oh well we can now read letters in envelopes because we have this x-ray technology what the heck now letters even in envelopes are public because we can read them with technology and once again this is not the way to argue you need to go through the steps and see what the disruptions are and how that affects long-held values so this this is the conclusion um still holds an iron grip ci reveals misalignment i continue to believe that these dominant ideas are detrimental to individual interests and denigrate societal and contextual values my approach would be to regulate with substantive rules informed by legitimate norms sometimes involving control but not always but using these ends purposes and values as the arbiters there's a lot of work to be done a lot of work and i welcome anyone to join in the effort we really need to change things up and that's it thank you now for the q a yes please um david rebus is going to be our q a maestro helena i'm gonna read out the questions for you but you can follow along too if you like in the q a box are you in the mood for helen for some uh very high philosophical questions or would you like to start with more grounded questions give me an assortment all right okay let's uh let's begin with the mark castle corn's question um he asks hi helen my question is about government databases that can be used to provide public benefit so for example to manage a major emergency and its impact on regional systems that government is loathe to create because they may contain private information and become targets of a foia and public disclosure request can contextual integrity help us find the appropriate balance yeah so this is this is a great question the it's a good question that some computer scientists or you know some policy makers want to answer by saying let's create the databases and then make them accessible through differential privacy so that we can extract you know the usual you know utility privacy utility trade-off which is an issue for me and i my pushback on this and it's not universal because i'm not saying that that approach isn't acceptable in some cases you know i think that um for many cases and i know there's a whole discussion of the census making the data available in in a differentially private way what i want to say is that if you consider the different parameters they're ways of providing the information different from the threat model that differential privacy solves so i'm i prefer to to offer a variety of approaches to say you can create the databases certain people will have privileged and you know what that is or to use this data and and or you're held accountable for certain uses of the data you you know you we create a system where we try and constrain the flow of that data according to the different parameters and i think right now we we've either we've talked about either you know releasing at all or um having it be and and having it be anonymized which we know cannot do or differential privacy which also has problems and i want to offer a different alternative to it where we might even make the data available in ways that could reveal identity but we do it in a way that's constrained i'm going to stick with another somewhat on the ground question um caitlin cork asks as cyber physical technologies become the norm in the built environment especially for uh internet of thing devices how do we ensure that the norms are morally justifiable do you see privacy concerns with aggregate data collected by iot device systems um the i'm not really sure why the iot i i can understand why iot devices escape the standard notice and choice regime i'm not sure first of all um when we say aggregated that they're different ways of aggregating so it could be that in order if you have some kind of fitness device and i'm sure and i imagine that caitlyn might include fitness trackers as an instance of an iot device then you would you might actually want that fitness tracker to keep track it could be useful for you to keep track of of aggregate like how much did you walk this week or was it better than last week and so forth and my colleague deborah estrin courses in small data versus big data when you're talking about aggregating across contexts so we're going to combine this data with shopping data and so forth then we have glaring violations of contextual integrity and we need to run these flows again through the machinery of the of the norms i don't know if caitlyn you can come back if if i didn't answer your question i'll look out for that all right let's shoot up to um the maybe the highest level question in the deck um but i think it's a fair question for a philosopher uh scott mainwearing asks my question is about the conception of information the contextual integrity theory appears to rest upon the metaphor of flow suggests metaphorically that information is a fluid object something that objectively exists in the world as opposed to say to ideas from critical theories that information is not quote unquote real but for example in some versions a social construction that is always in danger of being destabilized would you agree that contextual integrity depends on this kind of stabilized unproblematic idea of information if so does this create strengths and weaknesses of your approach um when it's interesting so the the term flow was was the term i chose out of a lot of different terms that i was considering at the time um because i wanted to be to not make assumptions about anything that was happening on the two ends and and here i am i'm stuck with it and the other thing i'm stuck with is the word context which has caused me no end of heartburn but i think your question i don't know that i understand your question as deeply you know in the depths to the correct depth but i will say this that when you take information of a certain type and of course the semantics of the information is is not god-given it's constructed within the context and and i am committed to that that the ontology that that different contexts are defined by different informational ontologies passes from one party to another party and the meaning of that data that information when it arrives to the other party could change dramatically and i want to just give it a very practical you know give a very practical reason because when it goes from this party to that party that party might have a bunch of other information that gives a whole lot of different meaning to that information when it arrives and this is why we have to be careful to um not just talk about party and party b but rather actor in a certain capacity and act in another capacity so i might have a headache tell the physician and the physician interprets that data that data gets a meaning depending on its arrival i don't know if that's what you meant scott and probably what you meant was deeper than that but i do accept that that the meaning changes in ways and that by including the recipient as a parameter you're allowing us to place constraints on what i'm calling flow which is just passage of data from one party to another oh great question i'd love to talk about it for hours but i won't um let's uh i'm just going to allow mark hasselhorn to do a follow-up um just to remind you his his question was about uh government databases first question he says follow-up is um so we can restrict individual access for public good he's asking i guess is that what you're saying um not quite as bluntly because um when because we can restrict in different ways yes so the answer is yes restrict but we can restrict in different ways and it used to be the case just just to give you an example that if you wanted information out of a court record you would go to the courthouse and you would be able to look at the material in the folder and that restricted access materially in a certain way the data brokers got around that because they hired people whose job it was and i saw this you would go to the courthouse you would you know claim all these and then they would just sit there and they would transcribe the information so there are various ways that you can impose restrictions you can impose use restrictions etc i think we don't fall into the computer science trap that says if you can do it that's all that matters and we we have to say well you can do it but we're gonna make it not okay just as companies impose restrictions on you know how you might use a copyrighted movie or something like that we can do it and then we need to think about that but but but it's important when we it's not like public interest writ large it's to understand what's being served when we do that so when we think about court records we the court record played an important function in the way the courts functioned whether to to achieve fair outcome you know equal outcomes for similar cases and so forth but then they became a mechanism to attach a reputation onto somebody and that's when things went wrong so we have to really define what that public what that interest is or yeah amy kelly very simply written question but i think it's quite deep hi helen i am wondering who gets to decide uh what the privacy norms should be in different contexts yes who should be responsible for ensuring that those norms are protected either by design or other means and three how can we trust um how much trust can we place in developers and especially users of various technologies to uphold privacy norms and goals i love that question um the second one the first one was who gets to the side the second one is who should be responsible for ensuring that their the norms are protected either by design yeah i'm i feel like maybe i placed you in the audience and paid you to ask that question so um because i i don't know who gets to decide because we have norms and by the way i'm aware that a lot of a lot of the norms that govern us and looking at it i'm not a critical theorist but i've been schooled by my critical theory colleagues who say that you know don't give too much credence to entrench norms because these entrenched norms may represent the interests of the powerful in society you know whatever gender race uh socioeconomic and not reflect the interests of everyone and by the way that is sometimes how technology can disrupt things in a good way so how norms become established in a society is when i say i don't know it's not like oh i forgot to figure that out it's to say there are other people who are much better qualified than me who have studied the evolution of norms in society and sometimes the norms are not you know equally good but we're going to assume that if we have a kind of reflective if we have a set of norms that we've reflectively evaluated then who is responsible for enforcing those norms or even passing the norms down from generation to generation and the answer is it's so interesting and complex not all norms get embodied into explicit rules we know that law is one vehicle for is that um responsible vehicle for promulgating and enforcing norms but norms can be family law uh you can be you know your friends can can push you away if you violate norms you could be part of a professional society that that lives that is defined by a set of norms and if you violate etc so the are many societal mechanisms for both expressing norms and for enforcing the norms and then the third question about how much trust to place in users and developers um part of what we try to do when we teach um when we do things like this is to create some sense of consciousness first of all that those people who are designing our systems pay attention so if you're designing a drone with a camera think about data flows and then should we trust you if you're working for a company that's invasive and etc so so there's this a lot of attention on things like professional ethics i think some of this is about trust and about promulgating in various different ways and some of it is about law and enforcement sometimes we have to enforce enforce the constraint in design and you know this beth that to this discussion of values and design sometimes we enforce it in design but design isn't the answer by itself i think this is going to be our last question okay from joe bernstein it is the most upvoted question uh i design enterprise tools for information privacy and protection most of our use cases aren't voluntary but for policy compliance such as gdpr do you think policy has negative effects of encouraging company to collect more information the more tools we have to manage data sharing and attempt to protect from breaches it feels like more companies now feel comfortable collecting data in the first place well that is so fascinating wow i don't think i'm going to be able to give a really good answer to that question because it it gets into the mind of incentives and and motivations but i do i do feel that we that we all held high hopes for the ccpa and for the gdpr and i'm i'm afraid that the achilles heel of both of these laws is that they utilize consent as this little loophole and so no matter what the constraints are they have so with gdpr there's one little bit of hopefulness in it because when you specify the the purpose so the purpose specification the idea of it is that you can only specify a legitimate purpose now if those folks were on their game they would say what do we mean by legitimate purpose and now we run through the whole contextual integrity process but uh i'm not seeing it happening and i'm afraid that because they give such a big role to consent we're going to it's it's it's going to be close to business as usual but i realize i haven't addressed that question because if you if you have a law that isn't very restrictive then the like kids you know they're going to push wow i'm not collecting all that data i think i'm going to collect more data because i'm allowed to and i do see those weird backwards incentives thanks for that quick thanks for those great questions all right thank you i think i'll have julie has some final words yeah thank you so much helen that was really interesting and thank you for taking the time to answer everyone's questions so i want to thank everyone for joining us for distinguished lecture today and i want to join join me in thanking helen one more time um either in the chat or or you know digitally clapping or however you'd like to uh share your things with with helen one more time today um also i wanted to thank again to the research committee for putting together the event as well as all the staff who put things together so wishing everyone a happy friday um and you wish you know health and wellness and perseverance until we can get together hopefully next year's distinguished lecture will be in person again but we'll now that we have such a great audience digitally we can hopefully uh maybe have a hybrid next year so looking forward to seeing you and and take care hi thank you helen that was awesome that was great thank you thank you yes thanks and see you soon

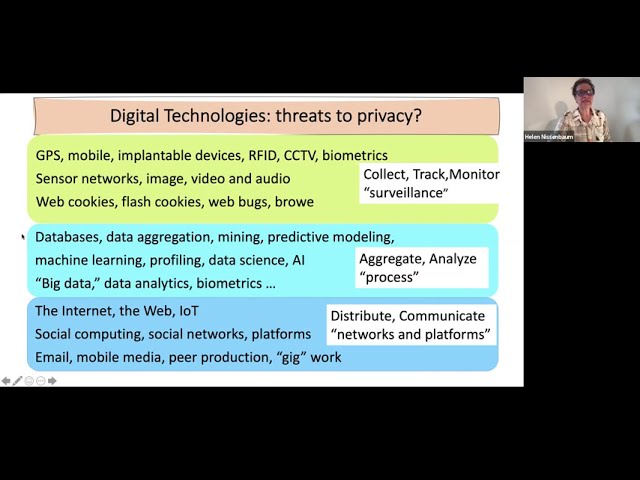

2021-03-13