Approachable Accessibility

So, my name is Samm Delorey. I use she/her pronouns, and I am the interim Assistive Technology Center Coordinator at UMass Amherst. And so in that role what I do a lot is I help students with assistive technology. And the way that I got into this role was I was a--I still am actually--a developer who cared a lot about accessibility, and so I would see accessibility traps and understand how that was affecting assistive technology and now I'm working with students and their assistive technology. So, I've seen kind of both ends of the spectrum. And I'm presenting with Elodie... [when I'm sorry, this was introduced, nobody knew it.]

[Sorry, my phone.] I'm sorry. I couldn't hear what just got said. [It was me. I accidentally ran some, some video. I'm sorry.] Okay. Elodie, do you want to introduce yourself? Yeah, sure. So, my name is Elodie. I use she/her or they/them pronouns, and I am a junior at UMass, and I'm double majoring in Psychology and Disability Studies. So, I'm passionate about disability-related stuff, including accessibility. Alright, so we're going to dive in. This is going to be just a general overview about accessibility and thinking about who is using the technology that you're building. So, one, like, important concept when it comes to, like, accessibility and disability accommodations in general, is the concept of equality versus equity.

You can give everyone the same thing, as you can see in this picture here, but that doesn't necessarily means that everyone's going to be able to get the same result or be able to achieve a desired result through the same, like, resources given. So, a really important part of accessibility is making sure that everyone gets what they need, instead of all just the same thing, so that they're able to enjoy and partake in activities, including on the internet. And so I'm just going to actually go back and I'm going to describe this image. So on the left, there are three people standing on blocks with a fence watching a baseball game, and there is a person who can't see because of the fence. There's someone who can just see over the fence and there's someone who has a lot of space to see over the fence.

And in the second picture on the right, they show the person who was tall enough to see over the fence has given his block to the smallest person and now they can all see, but it's very clear who is being accommodated. And so, something that we have been talking about a lot is universal design. And so, in the third, in this slide, there are three images. We have the two from the first and the third image are the same people, all standing on the ground looking through a fence. And so everyone can see without any accommodations.

And so, this is the idea of universal design. You don't have to out yourself. So a lot of people right now in the United States, one in four people have a disability, which, if you are someone who's trying to sell products to people, if you're trying to get people to use your services, leaving out people with disabilities is a huge part of your market. And so a lot of people don't like to reveal their disabilities or don't have the accommodations they need to seek the resources that they have if things are inaccessible. And so using universal design concepts and accessibility makes it so that everyone has access regardless of their disabilities, and they don't need to reveal disabilities in order to access the same things on the internet.

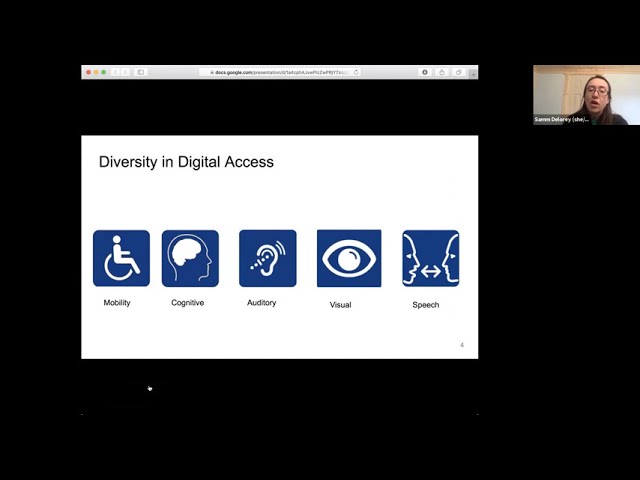

So, when we're talking about disability, there are five main categories that you should think about when you're designing things: mobility, cognitive disabilities, auditory disabilities, visual disabilities, and speech. And we're going to go a lot more into each of these and how people who have these various disabilities access the internet, access apps, access anything that you're developing. So, there are various forms of guidelines that exist for digital accessibility. Under the ADA, you are not currently required to have web accessibility and digital accessibility in general. However, it's still generally good practice to do so because like Samm said, there are a lot of people with disabilities. So, it's a huge proportion of the people who are going to be using web services, especially as some people with disabilities find it

harder to access the physical world and may be more reliant on the web. So, this is a link that people can look at more in depth later, if they would like, about just general accessibility guidelines. And Elodie was saying that these standards aren't necessarily legally binding for most people. So, we work in higher education. I work at UMass. We take federal funding. Because we're federally funded, we are required to follow the ADA, which is Americans with Disabilities Act, guidelines and also WCAG standards. But there's been a huge swath lately, of people and companies being sued by groups with disabilities, even in the public sector. Netflix is a big example, recently, and they're required now to have audio descriptions of all their new content. So, it's not just federal funded groups anymore private companies are being sued. Target had a big lawsuit recently.

And so, if you're able to incorporate accessibility from the beginning of things, it's going to make it a lot easier than remediating what you built when a lawsuit strikes, which is now happening, not just in higher education and federal funded places. And so also, what I had just mentioned, WCAG. We are currently using WCAG 2.1 as a standard but WCAG 2.2 is coming out soon. That stands for the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. And I have a link here to an introduction.

I could talk your ear off about this for hours, and we have 45 minutes, so I'm not gonna spend too much time with it. But the general idea is that anything built for people to access needs to be perceivable on any tool that people are using to access the internet. We're going to talk more about that. It needs to be operable, understandable, and robust. And when I first started doing this work, it was very different because most people were accessing the internet on computers. And now the shift has really happened and this is where the new WCAG standards have come, where a lot of people are accessing the internet on their phones, and that changes how a lot of functionality happens. You can't hover in the same way. Clicking happens in very different ways. And so, part of the idea of robust is that, not only does your technology need to work for people with disabilities now, but as new technology comes out and you need to stay with those standards, and keep up with

it. And it's a hard game to follow because technology is moving really quickly these days. So, people in general, when they're accessing the internet, they're coming from a lot of different places, whether it comes to disability or not. But when it comes to disability, they're all going to be coming at it from like different places, and even two people who have the exact same disability may be in a place where they have drastically different needs. So, it's important to consider, like, diversity and how the user is going to access technology in that they have the options so that it is accessible for them.

And one thing that I think about a lot, when I'm developing in regards to this is, I used to work a lot with a man who was born blind. And he was an expert screen reader user, and he could navigate, even things that weren't perfectly accessible, very well. And then I've also met brand-new screen reader users who may have developed low vision later in life, and it's much harder for them to navigate. And as a developer, I have to think not only of the experts, who really understand the technology and understand the workarounds and have other solutions when things don't work as expected, but also the people who are new because a lot of people develop disabilities as they age.

And so, we are approaching a huge generation of people who are aging into disabilities, whether that's auditory disabilities or visual disabilities are probably the two most common as people age, and we need to make sure that we're developing things that they can access, even as they're gaining new disabilities as they age. So it's also worth noting that while usability generally equates to accessibility, accessibility doesn't always equate to usability. So, the idea that something is usable is going to mean that a lot of people, most if not all people, are able to access, in this case it would probably be a website, and be able to use the service that they have.

However, accessibility doesn't automatically equal usability. There are examples that exist where websites are generally accessible for people. But just because they're accessible, doesn't mean you can actually read what the website says. I spent a lot of time searching for this image and I could not find it. But there is an example of a website that's just, like, all text. And while it was designed with a lot of accessibility principles in mind, it is practically illegible because it's just so much text. And then another example of this concept, a little more broadly, is the concept of disability dongles. So, disability dongles are basically technology that can be developed to solve some type of a solution for disabled people, but it's maybe not something that's necessarily so practical or that disabled people actually want.

So, an example of this would be a stair-climbing wheelchair. Instead of making the environment more accessible, you're just trying to fix the disabled person. So, while it is technically accessible because now that person can get upstairs, it's also always not super usable or the most practical solution.

There's an image that I think of that Elodie just reminded me of that's a cartoon, and it shows someone snow shoveling a walk into a school. And there's all these kids and there's a child also in a wheelchair who's sitting at the ramp, and the person shoveling is like, "Oh, when I finish the stairs, I'll shovel off the ramp." And the wheelchair user's like, "Well, wait. If you shovel off the ramp, we can all get in as opposed... like why are you making me wait to shovel off the stairs and then the ramp, when all of us can use the ramp." And so, that's an idea of, like, when you make things accessible for everyone, everyone can use it, and it benefits every user. A ramp benefits wheelchair users. It benefits people carrying heavy things. It benefits moms with strollers. It benefits someone who broke their leg and has a temporary disability. So, as a developer, making sure that you have those ramps built first before you add on staircases, make sure everyone can enter first, and then you may have a staircase that you want, that is a special feature, but you're not leaving people out. So, while we're talking about the end user, we talked about those five categories of disability.

And, I work in the ATC. I have access to a lot of different technologies that we have at the university, and we're open, not really during coronavirus, but when things start to settle down, if you want to come actually use these technologies, you can see how they work. And I would love to give demonstrations in real life, after coronavirus, for these technologies. So, this page is primarily showing people who have physical mobility issues and tools that they might use. So, in the top here, this says pointer. What happens when I click pointer? Well, look at that. And there's a moving banner that moves around. In this top left area, they're showing what's called a switch. And so one thing that's really, really important for developing for assistive technologies is making sure that anything is accessible using

keyboard only. Because a lot of people, both with mobility disabilities and people who are low vision or blind, will be using keyboard only to access your website. And so there's two really important things to do to make sure things are keyboard only, one of which is making sure that you can actually just, like, tab through a website. Because a basic switch, someone is only able to click. So, this switch here, it's a soft switch. Oftentimes, people might put them, it depends on your disability. People might put them on their shoulder so they can click with their head. Someone who has access to use just their arms may click with an elbow. Some people click with a foot. So, it's a one button thing. Imagine going on the internet to buy an airline ticket and all you have to do is click one button. You're going to go to the most accessible airline, even if they're going to charge you a couple hundred dollars more for a ticket, because it's so much less frustrating.

I read a study recently, I don't have the number in my head, but people are much more likely to just not buy a product, leave a website, leave a program that's not accessible. If I'm a student who's a switch user, and I can't access the admissions website for a university, I'm not going to go there. I'm going to find a university who's welcoming to me and makes their website accessible and keyboard friendly. This image... This is, this is such a fun pointer! This image up top is showing a wheelchair user who's using eye gaze technology for accessing their computer and actually at the end, I left on a slide, I think, that has an example if you have a PC you can download a free eye gaze technology called Camera Mouse. And what it does is it takes your built in webcam, and you can use it to navigate the computer. And if you try it out, which I highly recommend you do, you can realize how challenging it is to navigate a website using only your eyes. And so things to keep in mind when you're developing for people who are using eye gaze technology and technologies like that is it's very hard, it's very fatiguing when navigation switches. So I've seen a trend recently where websites have a top banner, and they'll do a sticky header so as you scroll the banner moves with you.

And that is really challenging for people who are expecting the navigation to be in the same place because to click an eye gaze mouse, you need to hold your focus in one point with your eyes for a second, which sounds really simple, but it's actually really challenging and that's the way that some people are navigating the computer. So, keeping that navigation the same is really important, and this is all laid out in WCAG. But the goal that Elodie and I have today is having you all think about the people who are coming to your websites and understanding why it's actually important to have consistent navigation, why it's important to have keyboard accessibility. I mentioned two things that I didn't actually say them. The other thing that's really important is a lot of software these days tries to reassign shortcuts, so they'll say, Hey... I guess I'll call it a technology I don't like. Hopefully, no one's on this call. I'm Hi, I'm Tableau. I made my own software. I've got this great data visualization, and I'm going to change the keyboard shortcuts to make it easier for our developers. What you've done then is take away a lot of built in navigation for people who use screen readers and people who use switches, and they're no longer able to access the content the same way they would. And it just really shuts the door on a lot of people with disabilities.

So making sure that you give your end user as much control as possible by letting them use their native shortcuts, by making things keyboard accessible, by keeping navigation consistent, is going to make it much more accessible. I mentioned screen readers a few times and I just wanted to make sure that people understand and if we have extra time at the end, I can demonstrate, because I actually do use a screen reader, a lot, myself. Screen reader technology is used by blind and low vision users to read off everything that's on the screen, and that's now true on computers, it's true on phones, it's true on a lot of different technologies. My friend who is blind says all the time, like, oh all my technology is talking to me. My watch is constantly talking to me. My TV is talking to me. And people are able to access everything that I can even if they're fully blind as long as things are built for them. So what is assistive technology? I could have probably open this up before, and I will read out a few examples. So we have no tech, such as detailed outlines for note taking. Colored paper note cards. This is why I'm not going to read them all. I'm going

going to stutter through them. Magnifying glasses. Braille. Picture boards. Large textbooks. Graphic organizers. Low tech would be videotaping class lectures. Talking calculators. Captions. Assisted listening devices. I'm going to read them all. Video description. Switch controlled devices. High tech is E-readers. Touch screens. Speech recognition software. Word processors. Computerized testing. And progress monitoring software. So, I switched my tactic halfway through and part of that is I'm working really hard, personally, on presenting for all users which is not something that I grew up doing as a presenter. And if someone is blind, and they don't have access to see this slide, I want to read it out so that the blind user has the same access to my slide as any other user would. So I changed my mind about that. Elodie, did you want to talk at all about the pandemic and how technology is affecting that now? And if not, I can. Yeah. So when it comes to the pandemic of course we're all more reliant on technology than ever, but for people with disabilities, this can actually be a huge opportunity.

There is a subset of folks with disabilities, not all of them, who haven't been able to, like, get out of their houses on a regular enough basis to, like, work or hold a job, and it seems like it used to be very common in the workforce for people would be, like, no, you can't work from home. That's for, like, our upper level people only, and you're not that. But now, it's pretty clear that we can all work from home, or at least a lot of people can. So, with that, like, all of these technologies have popped up, like, Zoom. I'm going to guess that most of us probably didn't know what Zoom was a year ago. And even today, we have captions, and the fact that we have, like, accurate captions on things like Zoom, Google Meets, it just is such an increase in accessibility and it's come from the pandemic. And it's also kind of a beautiful example of, the caption specifically, or a beautiful example of how in order for an assistive technology to be most effective, it doesn't necessarily have to be the highest tech solution. We have, like, the low tech captions here that are likely making the presentation accessible for more people than it would be otherwise.

And as another example, I have the example of taking notes because I happen to know three different people who use three different methods of note taking. So, I have a friend who tried using a high tech scanner pen to take notes, but it just, like, wasn't super accurate and didn't work. So, now that friend uses Echo360 which is a way to record lectures that are happening. And that's, like, a solid low tech solution that works well for him.

Whereas I have another friend who has been offered Echo360 but would really just prefer, like, a hand copy of, like, notes from a class. And then, myself, I don't find Echo360 or notes from other people particularly helpful, but I have a computer pencil that I use, and I use a touchscreen computer, which works a lot better for me than taking notes on pen and paper. And so that's a little bit more of a high tech solution. But just different stuff can work for everyone. And it doesn't necessarily have to be the most technologically advanced solution for it to be effective. And also, to go back to the image of the shoveling snow from the ramp and the stairs. Captions help many people not just people with disabilities. There is evidence I've seen that 96% of students in a class who have captions on, focus more during the class. They have higher grades. And I think 73% of students choose captions, even if they don't have a disability, when they're available. So, assistive technology is able to help everyone, not just people with disabilities and that's actually been a really big benefit for

the community of people with disabilities because, a lot of technology that we're using now has been developed just very broadly. So a lot of speech to text and text to speech was developed for just general populations. Things like Apple taking over Siri and voice technology has really advanced things for people with disabilities as well and it's been a really good experience. So I talked a little bit about switches already. There's a lot of different switches, and these aren't all of them. We'll share the slides after and there's links that you can click and find more about. Another example of a switch for people who don't have any mobility is there are small switches that can be adhered to a face so you could just wink an eye to click a computer button, which is so cool. There's something called a sip and puff, which is basically just a straw that someone can click by blowing or sucking. I just did the opposite. Like blowing or sucking to control their computer, like, there's so many people who are accessing technology in ways that I didn't think about until I started going into this field. So there's eye gaze and hands free.

These are some examples of people using that. And it's fatiguing, and so if people are going to be accessing what you're building, making it as easy as possible to navigate, to find what they're looking for, is so important. Again, you can click this to follow about what eye gaze technology is, and at the end there's a link, you can try it out if you have a PC.

Alright, cool, we're doing pretty well for time. So if you want to connect with us, both Elodie and my contact information is here. And we also have a link. UMass now has an accessibility page where you can both find resources and report accessibility issues, which is awesome. And I left a little time, and I think I'll play around for a little bit and then leave some space for questions, just to show.

So on the next slide after this. This is a website. Now I need to figure out how to share a different screen so you're not just seeing my slide. You're going to see like messy desktop, and it's recorded for posterity so that's exciting. So I'm going to click. Oh, you know what, I'm in Safari. I don't know why I'm in Safari. So there's a lot of different tools for doing accessibility testing. And you can use a lot of automated tools to do testing, to just get an idea of what's going on, but nothing really makes up for human testing.

Because a tool can tell you something is inaccessible or warn you that it might be, but it's not going to give you a full report of how to make things better. But I use a tool called WAVE, which you can get as a browser extension. And when I pull this up, this is going to tell me that this web page that I'm on in my browser has 21 errors, contrast errors, alerts, features, structural elements. That doesn't tell you much.

So I'll go into the details. So, it's showing me that some images here are missing alternative text. Alternative text are used by screen readers and other technologies and also if an image doesn't load, it will display alternative text. Sometimes you see that little bar. And so, alternative text is a means to describe an image for people who wouldn't be able to see it otherwise. If an image is strictly decorative, you can have null alternative text which would mean that a screen reader can just jump over it and not see it. But if an image is conveying any meaning, it should definitely have alternative text. What's great about WAVE is that it not only tells you what the errors are but it will give you details. So for example, if I didn't know what alternative text

was, I could click this and it's going to spell it out for me explicitly, what it means, why it matters, how to fix it, and the WCAG standards to fix it. So, missing form labels, the same thing. I can get that information, how to fix it. I honestly could talk about this for days. So, if people have questions, I would love to reach out. Alt text itself is really challenging because the context of what you're describing really matters.

So, an example I use a lot is, how would you write alt text for an image of a sunflower. Does anyone want to speak? I think you're able to speak. I'll give you a few seconds. Anyone wanna answer? I can't tell if people raise their hands. Where's my participants? All right, no one's raising their hand. Elodie, can you give me a guess as to how you would label the alt text for an image of a sunflower? Well I would start by describing it as, I don't know how many petals there actually are on a sunflower but how ever many, are sunflowers round on the end? Whatever shape the end of the petals are. Petals with a brown center. And then I'd need to know more about the environment that the sunflower is in to provide much more of an image description. Yeah. And so what Elodie said, sorry to put you on the spot, Elodie, it really matters. The context matters. If I'm writing a blog, and my blog is just text and I want to spice it up, and oh, hey, I took a picture on my phone earlier today of a sunflower, and I throw the sunflower on there just to make it more exciting, more inviting. That's just descriptive image. If I was a screen reader user, I wouldn't want to know about that image, and I definitely wouldn't want. If you don't give alt text, it will often read

the name of the image. So, in my case, if I grabbed it off my phone it would say, IMG_1257, and as a screen reader user, that slows you down and makes it harder. If I have a website for a seed catalog and I have 70 different types of sunflowers, what the image of the sunflower looks like actually matters because I'm trying to sell people these different types of sunflowers. So like Elodie said, I'm going to describe the shape, I'm going to describe the size, I'm going to describe the color in the alt text because the context of that matters for the image alt text. If you Google, you can probably find it. There's something called an alt text Decision Tree that the w3.org put together, which is so helpful

for deciding what alt text you need. So, it's just a flowchart. Does it contain text? No. Continue. If it does all of these steps because, even one image, the alt text is going to be so different for that image and all these different contexts. And it's a really challenging topic. And again, like I said, I can talk about this forever so I'm going to move on.

And now you can all see everything. Quickly, before you do. There was a question asked by Cheryl. Is it because, in that case, I think you were referring to the sunflower, Cheryl, correct me if I'm wrong, is for visual interest but it's not meaningful? Yes. So, if it is for visual interest only. Like, I work at UMass. That's true of a lot of the images on most of our websites. They're just descriptive. And so it just takes time away from a screen reader user to have alt text, and what the behavior of a screen reader does if it has null alt text which, in HTML, would be alt="". In different tools, it might be different things. I do Drupal development.

In Drupal, if you have a field, you can leave it blank and that will create null alt text but you need the alt field there, or else it won't. Or if it is inline HTML, then you need to do the alt="". But yeah, we can even just go. I'm going to go to a UMass web page I know this isn't a UMass-focused event, but I work at UMass so that's where my brain goes. So, this is a picture of a campus tour. And because below it, there is a description of the tour in text that any person using the Internet has access to, this image could have null alt text because the person below can understand what is being conveyed. I'm just looking at the UMass Hotel. Background images are a really good example of where you don't need alt text, where in fact you want to have null alt text. This image isn't really conveying much to me as a reader.

It's just there decoratively. But here, as I go below, there is an image that showing me that there's free Wi Fi. There's an image that's showing me there's bikes. And there's an image that's showing me complimentary breakfast. That is conveying information. As a screen reader user, I want to know that information, and I would be left out from that if it's not conveyed in alt text, and I'm not positive. Oh good. So in this case they did a really good job. This text is actually HTML. So that is accessible to a screen reader user and we can just look and see the alt text on this image. There is no alt text on this image.

And because of that, there's no alt text, and there's no null alt text. So most screen readers would read out this image name, which is unfortunate. So if I was using my screen reader and say image, UMass Hotel COULIC2.png, which is just a waste of time. So, if the way to improve this would be to give that image alt text. I want to make sure I'm not missing other questions because I don't even see the chat. There we go. Alright, we've got a few more minutes so instead of me just play around on the internet.

I would love to answer some questions and I can go through questions in the chat or if you want to ask questions out loud. But also I would love to connect to people, like, I'm very happy to do so. This is a short period of time so please reach out. I'll put back up my contact information. Recommending test tools. It depends. If you want to use free tools or pay. Always, paying for things are going to be better than free tools. I think WAVE is great. They have both the browser tool for Chrome, but also you can just go to their website, which is at WebAIM.

And if you go there you can put in any URL. Sorry that UMass is stuck in my head but we'll do umass.edu and it will crawl through that site. And it will provide the same breakdown that it does in the web browser tool. However, there's a lot of them, and I can put together a list. It's what you're interested in. I really like WebAIM because it breaks down what's wrong, why it needs to be fixed, and how to. Because, if I'm sharing this with other people just not doing the work myself, I can just take that and say hey it's really important to fix your form labels, this is why, and then I don't have to go through it each time.

And this will be an awesome resource. I can share it and I'll share it with the NERD Summit people and have them send it out to people who have attended. Is their a standard for telling a screen reader to just ignore an image? So, screen readers vary and there's actually two distinct types of screen readers. There are screen readers specifically for blind users and there are screen readers for sighted users who may use them for other reasons. And by default, screen readers for blind users, if you set that HTML to have the null alt attribute, the screen reader will skip over that image. So in HTML, it's alt equals... Here, let me see if I can find a good, I'm sure WebAIM has a good example. Can you all see my screen still I'm not just sharing... Yeah. Okay, great. So you can see here's a good example in HTML, here's the image and WebAIM has they're alt="WebAIM - Web Accessibility In Mind" so that is their alt text. Let me see if I can find something that might have a decorative image as background image.

All right, I don't want to waste your time. But yeah, it's alt equals two empty quotation marks will just make most screen readers skip over a null image. I'm just going up to the chat. If you have questions and want to ask them out loud, feel free to if you're able. I think that Cheryl has their hand raised. I do. Should I just jump in with my question? Yes. Go ahead, Cheryl. We're having a conversation, especially because Zoom has rolled out the transcription that some of us are using within this to watch. And it's automated so it does make mistakes, and it also allows me to download those mistakes as a persistent record.

Do the benefits outweigh the problematic portions especially when it's something, you know, that could be offensive, right, that's persistent? Just as an example, yesterday we were running with captions, and it was my birthday and someone with an accent said, oh, here's the cake, and it said here, defecate, right, so it was a rude and it could have been seen as taken out of context. So how does the benefits outweigh the costs in terms of that when you're using the automated captions which are certainly like 80%? So, I would say, it depends on your audience and things like pre-planned events where you know people have accommodation requests, it's really important to meet those requests. And so there are better tools even built into Zoom that cost money that are worthwhile. So, Carte Services, another option in Zoom, is you can pay a transcriber, a live transcriber, to be there and participate. And so if people are are having that as a request, that should be met, especially in higher education and federal-funded events, you're actually legally required to. The same way that if someone asked for wheelchair access to an event, you would be required to. In regards to things that are being recorded and saved afterwards,

if you're able to edit those transcripts, that's the best practice. Actually, Elodie and I were both in a meeting yesterday with a man who had not seen the auto transcriptions of Google until recently, who was hard of hearing, and he was really impressed with how well it works. And I think for most people, the technology has come so far and made things much more approachable to them that it outweighs the benefit. We're used to things working so poorly that it's like, oh, 80% is actually pretty good and if I'm hard of hearing and used to just lip reading, I'm getting a lot more from 80% accuracy than not. However, if you want to show people that you care about accessibility, pre-recorded videos and things that you're saving, fixing those transcripts are really important. If I go to a website that's like, we care about accessibility, and they don't have captions on their videos that are pre-recorded, I'm like, you don't actually. You're just blowing hot air. I just saw a new chat.

I also quickly wanted to mention with this question. I think once again context matters, too. Like, for someone who is hard of hearing, or deaf, it might be, like, more important for the captions to be correct. But I also know there's a lot of people who use it for other disabilities. I have a ton of friends with ADHD, who say they love the captions, but could probably still pick up on, like, discrepancies between the captions in the audio and do understand what people are saying. So in something like that, having, like, the auto transcription is great even if it's not perfect.

So I think it's worth noting context as well when it comes to auto captioning. Victoria mentioned in the chat, that if you're uploading things to YouTube, there's an auto captioning system that you can edit and that editing is so important, and it's actually pretty simple. YouTube can assign the timings and you can just go in and the same way you would in any other text editor, just fix it and save it and then you'll have hundred percent accurate transcripts and captions which is awesome. Alright, sounds good. Thank you so much, Samm and Elodie. This was a wonderful presentation. I'd love to have you back for NERD Summit when we're in person, Hopefully next year.

Yeah. And if people want more information, we'd love to reach out. We can do a whole thing on alt tags, we can do a whole thing on captions, like, there's so much information. Yes, there is a ton of information.

2021-03-24