Carbon Pricing in the Real World

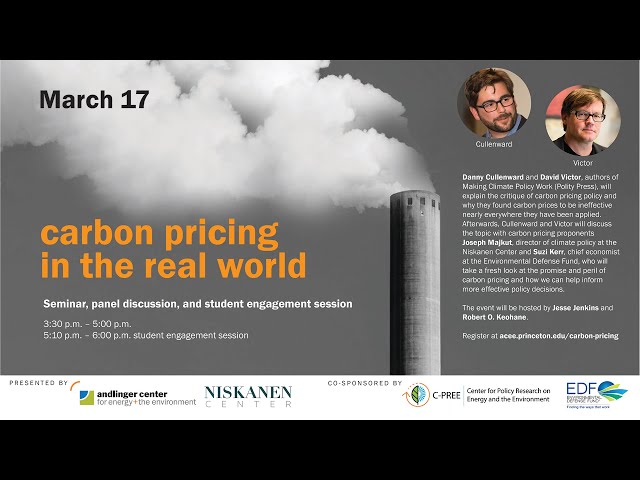

hello and welcome everybody i'm excited for today's event on carbon pricing in the real world i'm jesse jenkins at the andlinger center for energy and the environment at princeton university and with the department of mechanical and aerospace engineering and on behalf of princeton's andlinger center and our partners for this event at the niskanen center and our co-sponsors of the environmental defense fund and the center for policy research in energy and environment at princeton school of public and international affairs thanks everyone for attending i wanted to give a bit of an introduction to this event before handing things over to our panelists and moderators we've got a great uh hour and a half or so in store for you today and i was motivated um to put together this event by the publication of danny cullenward and david victor's recent book making climate policy work which landed on my doorstep around the winter break and which offers a cogent and constructive critique of how carbon pricing policies work in practice across the world carbon pricing could be the most powerful tool in our climate policy arsenal by putting a price on carbon pollution that's equal to the societal damages caused by an additional ton of climate warming carbon dioxide policymakers can provide incentives that reach all corners of our economy and incentivize decisions by businesses and consumers to consider the economic costs of climate change in all of their decision making by internalizing the cost of carbon emissions in this way and by which can be implemented either through a carbon tax or through emissions cap and permit trading programs is widely regarded as the least expensive and most market-friendly way to drive down greenhouse gas emissions and confront the threat posed by climate change there's only one catch governments around the world consistently fall short in their efforts to price carbon danny and david's new book offers a look across the world's experiences with carbon pricing and provides a useful diagnosis of the real world challenges that carbon pricing faces in practice and i think a constructive set of recommendations for how we can do better going forward so i'm excited to welcome our first panel which will include uh danny and david um and then we're gonna have some further discussion later on by suzi kerr chief economist at the environmental defense fund and joe majkut of the niskanen center uh who are going to offer a more proactive or positive spin um on in their experiences working through policy making channels to try to implement carbon pricing so to briefly introduce our first panel danny cullenward is an energy economist and lawyer working on the design and implementation of scientific scientifically grounded climate policy he's the policy director at carbon plan a lecturer at stanford law school and a member of california's independent emissions market advisory committee where he's had a front row seat to the implementation and administration of california's greenhouse gas cap and trade program he holds a jd and phd in environment and resources from stanford university david victor is a professor of industrial organization and innovation at the school of global policy and strategy at the university of california san diego where he also holds numerous courtesy appointments reflective of his work at the intersection of energy climate change politics and policy his research focuses on regulated industries and how regulation affects the operation of major energy markets and their impact on climate change he's the author of several books on international climate policy and politics each of which is required reading in my view and he's a fellow alumni of mit where he earned a phd in political science i'm going to hand things over for the rest of this event tomorrow a gust moderator today robert keohane an emeritus professor of international affairs at princeton university he's the author of after hegemony cooperation and discord in the world political economy among many other important works in the fields of international relations and international politics professor keohane is a member of the american academy of arts and sciences the american philosophical society and the national academy of sciences as well as a corresponding member of the british academy i'm going to hand things over to bob now to to moderate our first event our first portion of the panel and just want to note that uh we are going to be taking questions from each of you via the q a portion of the uh uh of the zoom uh features here i'll be monitoring those and passing things along to uh our discussions uh and with that i'll hand things over to uh professor keohane oh thank you jesse it's a great pleasure to be here uh david is an old friend and i know danny as well as well as well as suzi so it's a it it's a good event because we are not debating whether climate change is real and we're not debating whether to do something about it we're having a more serious debate on what to do about it and how large a role congress prizes should play or should play uh the national academies of sciences uh issued a recent report in february which i recommend to all of you which is kind of ambivalent about current prices so it sets the stage for this debate they say yes there should be a carbon price of forty dollars a ton but they don't put emphasis on it and and the chair of that panel stephen pacala in introducing it indicated that all of the recommendations he thought could be fulfilled without a carbon price so that it's it's carbon price but it's not essential to so they're kind of on the fence about this which indicates that this is a topic which uh is a live topic that divides people who are otherwise on the same side of most issues who are serious policy analysts studying climate change uh in a uh in a uh sustained way so we'll start with david victor and and danny hello and dave is going to speak first and then danny excellent well thank you very much bob and jesse and princeton and all of your affiliates for the invitation it's really terrific to be with you here today and i think the introductions that both of you made really set up the question in front of us which is um it's easy as a political scientist to be to explain pessimism around climate change and the lack of action but the reality right now is there's a lot happening and more could be happening uh a lot of technological progress and so the question right now for for us analysts is which policy instruments really move the needle it's been a huge the literature for the most part has been around what things cost what is technological feasibility all important questions but ultimately serious climate policy requires putting together and holding together a political coalition and that's what this book is about it's about the politics of instrument choice of policy instrument choice we're very focused on uh throughout the book on market instruments of two flavors cap and trade systems so quantity measures uh carbon taxes uh price price measures uh because the empirical experience is mostly around uh around cap and trade the core of the book is a lot about that but we're also going to have some observations about carbon taxes and also frankly how to make cap and trade systems a little more tax-like because the politics of that are are easier what's new in this study is uh is a a theory of politics and attention to uh to political behavior and what's also new is uh is empirics it's been enough experience now with with market-based instruments that we can lay out some some basic theories about how the world works politically and then see whether the the actual experience with uh with with market-based instruments uh survives contact with that theory and that's what we're gonna what we're gonna be uh dealing with today so here's a picture of the book which is available on amazon so we can send money to jeff bezos if you're interested in buying the book and then i want to just put to go go straight to the next slide which sets up the puzzle that we're going to carry through the presentation today what you see on the left side is world bank data showing since 1990 the fraction of global emissions year by year that come from jurisdictions that have carbon market systems in one form or another and since the middle 2000s that fraction has risen with the uh in particular with the arrival of the european emissions trading scheme and then systems in california the northeastern states the so-called reggie systems uh this year we have rolling out and kind of haphazard ways the chinese system so now you have this big rise in the role of uh in the world of market-based instruments and uh uh and and it seemed and at the same time a lot more action on climate change so look on the surface that that um uh that the use of market-based instruments coincides with with policy action what you see on the right side though are the actual price levels um so about 85 percent of world emissions are currently have effectively no no price right above that you see the price levels that are consistent with the reggie uh system in the northeast so less than ten dollars a ton above that you see cal price level is consistent with what we have in california seventeen eighteen dollars a ton you have the european uh levels above that and you have point three percent of global emissions have a price that's above that's above fifty dollars uh fifty dollars a ton so um that's a pretty big puzzle which is we see the a huge use of uh of market-based instruments but when you look closely at the actual price levels it's nothing like the social cost of carbon and frankly also it's nothing like what societies are actually spending when you go look at the cost of the policy measures like renewable portfolio standards energy efficiency measures a variety of other things that real governments uh run by politicians that need to to hold on to power that they've been putting into into place and so that's the the big puzzle that we're trying to explain uh throughout this book um our explanation that we offer is uh is through a lens of political behavior and it's not just kind of politics is hard and so on but we're trying to provide a systematic explanation for the political behavior that we have that we observe in the book we look at institutions institutions aggregate interests and make decisions and the voting rules and institutions matter and so on and then we also look at five major interest groups or organized potentially organized interest groups of which three do most of the work we look at incumbent emitting industries they're very well organized they know who they are because they already exist and they know what the consequences might be of policies that change the status quo they're typically very powerful we look at voters which for the most part tend not to be that well organized around climate policy especially in opposition to climate policy except in those in a few sectors where climate policy has visible effects uh like in transportation fuels where people know to the decimal point what the cost of gasoline is and how it might change as a result of climate and other kinds of policies we look at political leaders who are democratically responsive and are often playing pioneering roles in creating markets my former governor jerry brown for example civil society organized civil society we look at in the book most organized civil society think ngos is not that heavily engaged with carbon markets joe's organization susie's organization are among the few exceptions and then look at emerging low-carbon industries which tend frankly not to be that well organized and focused on carbon markets because if you're a fledgling new industry you're much more interested in direct subsidy or market support or market access then then some abstract uh ephemeral and distant impact of a gradually rising carbon price into the future so what we think is that these first three interest groups do do a huge amount of the work and explaining what uh what happens what we observe empirically in the real world with this this now huge experience with using market-based instruments to try and address the climate change problem and over the next few minutes danny and i are going to talk about four observations there are many more in the book but four observations are going to help give you a sense of what our our core our core argument is and the first observation is that one of the reasons if not the central reason why prices are so low is that um the the organized interest groups incumbents are often opposed to policies that alter the status quo but their power becomes much greater uh when when that opposition is also magnified by other interest groups such as uh such as voters and so you see in essentially every market we've observed in the real world you see what we call potemkin marcus after the fabled tsarist villages where you take the czar out to show how beautiful the construction project has been and so on as long as nobody looks behind the facade it all looks like the facade is beautiful or in our case that the market is actually doing uh doing the work this is a shutterstock image that dave roberts included in his volts newsletter the three-part series about about the book for cap and trade systems this problem is particularly uh severe because in every market that has a cap and trade system most of the emission reductions is being are being implemented through regulatory policy instruments uh direct action industrial policy a handful of other of other things and not the the market-based instruments think that the cap and trade system in effect is trading a residual you have other policies like renewable portfolio standards that cause emission reductions and then whatever is left over gets traded uh as a residual so the prices that come out of the cap and trade system don't in fact uh reflect the real marginal the real marginal effort that is being made by by firms there there's been a whole series of empirical studies that have now looked at this among other others seven bornstein's recent piece the american economic review and a lot of other research and we present a lot of that a lot of that in in in the book so this is a huge problem and one of the things we grapple with in the book is is this does this exist because policymakers were asleep in economics 101 when they were learning about externalities and if they only learned more economics or we yelled louder as policy analysts would uh would they do to do something differently and we think they weren't asleep we think they were wide awake they they they knew what they saw and from a political point of view a lot of what we love about markets transparency fungibility across different sectors the ability for the market to find out how to allocate costs and benefits that's a horror show for politicians who want to put together and hold together political support for uh for a policy instrument and so that's why they favor direct intervention and regulations because you can manage the politics of that uh much more much more easily this same challenge exists for for carbon tax instruments one of the good examples of that is norway which has one of the highest tax environments in the world and yet the most important pioneering carbon capture and storage project that's being developed right now in the norwegian market is a is a project the northern lights project that could not be justified on carbon tax grounds alone it required direct and substantial support from the norwegian government and the european government so we see this pattern all around the world this this potemkin markets uh pattern that uh is the core explanation for why prices are low even as governments are making significant efforts and i want to underscore that the book that we've written is not an anti-market book danny and i are both trained in that in that discipline it's a book that's trying to look at whether the the ideas the elegant ideas of using market-based instruments can work in the real political world where there are organized forces that often want to keep your policy from being being effective and a key part of politics is managing the incidents of the costs and benefits around groups that otherwise could block completely block your policy another thing we spend spent a lot of time in the book discussing is the coverage of different sectors and the the different interest groups that that are relevant for uh for climate policy are organized in different ways in different in different sectors and so one way to think about this is on the vertical axis is the extent to which there's a demand for a for a for a policy response uh the extent to which uh actors are organized they have the capacity to block policy where you see transportation fuels at the absolute top we think the transportation fuel problem is in some sense one of the hardest because the public in much of the world is so attentive to the cost of transportation fuels electric power sector uh in the bottom right is the opposite it's not that the power incumbents in the power sector are indifferent to the cost of policy but it's the government also has the capacity to adjust the incidence of costs uh on those different groups in ways that keep the politics together and that's the horizontal axis is think of this conceptually as the size of the toolkit available to policymakers to respond to politically well-organized organized groups in the power sector the tool gets really large direct regulation tariffs and so on the transportation area the toolkit is much smaller but for the capacity to simply remove or water down the policy and this is why uh cap and trade systems that or tax systems that link together multiple sectors follow the advice of good market design often end up stuck with prices that are extremely low because the politics of the least ambitious sector the transportation fuel sector end up driving the politics of the system uh the system overall one of the ways you can test this theory is to go out into the real world and look at the actual incidence of carbon prices which is what we show in the next on the next slide uh using this using amazing data set the jeffrey dolphin originally cambridge university put together that looks it looks at the carbon price sector by sector for all of the economies that have market-based instruments in place if the nominal carbon price or the price that's in the law or the price that comes out of the market were applied to all sectors then you'd be on the 45 degree line shown in the in the dotted uh gray lines there but instead what you see is the economy-wide average price is much much lower because there are sectors that are fully exempted uh from from carbon pricing and and uh or pricing levels are reduced precisely because those sectors are politically very exposed think for example the swedish steel industry where you have the highest carbon tax in the world across the swedish nominal carbon tax in the world and yet the steel sector is exempted from the vast majority of that because swedish steel could not compete in the global market global commodity market if it didn't have that kind of exemption and so this is the real world of politics and one of the ways you see this is in the is in the actual prices that the economy experiences as opposed to the idealized theoretical prices which is where we tend to focus a lot of our a lot of our research hopefully our research until now so i want to hand it over now to danny who's going to do a deep dive and look at the situation in california where you can really see this difference across different sectors as and the data are particularly rich danny thanks david uh and thank you to jesse and to our discussion so joe and suzi really appreciate the chance to be with you all so i wanted to show you a picture that brings together a number of the concepts david's just talked about and i think california is probably the place where the data are richest and allow us to speak most clearly about these issues in a comprehensive manner so i'm showing you a number of policy measures that the state of california pursues on climate policy and on the left-hand side you see our cap and trade program which covers about three quarters of the state's emissions it covers all three of the sectors david just discussed and as a result the politics are very very difficult to move this system to a higher ambition higher price outcome you've seen prices stuck basically at an administratively determined price floor for the market's entire history currently 17 18 a ton when you start to look at individual sectors in california you see a very different story california has a famously ambitious renewable portfolio standard and after hawaii was the second state to push for 100 clean electricity uh in a major bill that followed actually a very contentious bill to extend the cap and trade program and help perpetuate these politics that we've been talking about um california's renewable portfolio standard when you measure the cost effectiveness you measure the cost of carbon that's being reduced we're pushing a lot harder on that and we're on the direction of moving into a zero zero grade implementation pathway um arguably because you're looking at a single sector where the politics are easier to organize the public perception around the benefits of moving to clean energy easier and the cost implications simpler for policymakers to manage although by no means a simple matter as jesse and others know we see similar examples actually i think maybe the most important and prominent one is in california's low carbon fuel standard which is a actually itself a carbon pricing program that applies to just a single sector to transportation fuels that are sold in the state and that program trades at around 200 a ton these days what's so interesting about this policy is that if you go look around the world that a lot of the people who are pursuing some of the most aggressive climate mitigation strategies including direct air capture as well as some of the efforts to develop negative emissions or carbon capture and storage facilities in california everybody's looking at the lcfs as a primary means of financing these breaking edge technologies because it delivers such a high price signal that's so valuable it helps bring new technologies to market almost an order of magnitude higher costs i guess a little bit more than you see with the overall economy wide cap and trade program and you see results that are very very different because it has such an ambitious price trajectory when you take a step back california is about to go through a scoping plan process to think about how it's going to achieve its carbon neutrality goals by mid-century and how to achieve a legally binding 2030 emissions limit the last time the state did this it looked at a portfolio of policies many of them significantly more expensive than the cap and trade program in no small part because they're also much more ambitious and a range of costs up to 200 a ton as well there when you open up the hood on the spending side of these programs which is something very few people have done particularly in the context of political thinking around carbon pricing you see an even wider range of outcomes now some of the spending is what i think ungenerously you would call pork pork is a big part of how political systems operate and we shouldn't run away screaming from it but you often see some of the expenditures targeting really ambitious and beneficial activities you also see interest groups scrambling to label their preferred expenditures green and to sort of come in under the line in that sort of way so you see a wide variety of outcomes in terms of the effective carbon pricing that's in place and this this macro economy-wide cap and trade program sort of sits on top of it and creates the mirage that we're using a market-based approach when in fact we're driving our progress with very different strategies and techniques california is not alone in that and we think is is typical of the politics that we talk about in this book the reason california stuck on low prices on cap and trade is if you want to adjust the program to make it do a bigger share of california's climate policy agenda you're going to raise transportation fuel prices and that means anytime you want to move forward with this instrument you fight industry you fight the oil industry you fight the major emitters like refiners you fight all of the manufacturers you fight the food processors you fight them all at the same time rather than thinking about step-by-step opportunities to regulate subsidize do public expenditures set performance standards you can go step by step with those alternate approaches and that we think is a big part of the reason you have to have such different levels of ambition in places like california the story for the european union is somewhat different and we wanted to call out the experience with the eu because the eu has been a major success story in our view and it's something we talk a lot about in the book we also think it's an exception and that the conditions you see in europe are unlikely to be found in very many other places europe very famously these days has prices they're almost at 50 a ton these days this is a couple of months out of date these data remarkable high prices right now that are pushing uh europe's electricity sector to clean up its act including with member states that have historically favored coal so this is a big deal in the electricity sector and it's it's a really good outcome as far as we're concerned but it also follows nearly a decade of prices being stuck in extremely low gear as europe first began importing over a billion questionable offset credits from international offsetting and burden-sharing agreements under the kyoto protocol era as well as suffering the consequences of a massive oversupply problem that is related in part to the policies of its member states which let california push on other measures and the effects of the great recession from last decade it took extraordinary efforts to improve the capacity of european regulators to centralize political authority and ultimately set up major reforms that began a couple of years ago that pulled all of this together and the europeans have demonstrated how to do that in a very effective way that we think other markets should copy and consider but there are a couple of problems that europe hasn't solved that everyone needs to be paying attention to because for all of the success of this case study and it is a very big success we have a couple of major problems the first major problem europe is living through right now which is that this program applies to its industrial sector and that means all of the trade exposed industries particularly those operating in international commodity markets are facing major competitiveness concerns and the standard textbook answer that uh analysts today gives well let's just do border carbon adjustments let's come up with trade measures that equilibrate the price of carbon at the border rebate the exporters charge the importers and now we have this even playing field through this beautifully designed concept the problem with border carbon adjustments beyond the fact that they're wickedly difficult to do in practice is that the politics don't necessarily cut in that direction it was assumed that when europe was pushing very very hard on these measures that it would increase the possibility of a club of climate-oriented countries to come together to advocate for border carbon adjustments what we're seeing instead right now is the united states which has talked about these kinds of issues in the past is also signaling maybe there's cold feet in the u.s because europe's border carbon measures would absolutely be applied to and potentially target u.s imports and if you think the united states reaction to border carbon adjustments is tense or complicated i promise you the indian and chinese trade perspectives are even more significant and challenging as far as border adjustments are concerned if you can do a border carbon adjustment you can address this problem but the politics we think are much more complex than many analysts oppose the second issue that is essentially unresolved in these political systems is the question of transportation fuel price impacts which are the most politically salient for the everyday voter and the standard response to this which i think is absolutely good economic policy uh but which we believe may be much more politically tenuous than many people want to admit is the use of a significant dominant possibly even universal share of the revenues collected by these programs going back to households in the form of flat per capita rebates or other forms of progressive income transfers now the fact is when you transfer on incomes like this you end up making the lowest income households better off so there is a net progressive effect of a tax on carbon or a price on carbon combined with these rebates but it's a very difficult political proposition i put up here two groups the citizens climate lobby a grassroots political organization the united states that advocates for these policies and an industry-backed group called the climate leadership council which does the same the major difference between them is the third rail we need to talk about in the united states which is that most of the industrial proposals those backed particularly by the oil industry also come with significant regulatory rollbacks and the prospect of trying to roll back regulations that are favored by many stakeholders at the same time you're sort of betting the farm on border adjustments and dividends i think that's a very unstable design even though it's one that on paper i personally support i've even worked on legislation to do this in the past at both the state and the federal level people don't like it and we need to talk about that the last thing i want to say before we wrap up is the problem of how most markets have responded when they've been unable to successfully tackle the problems i just discussed and that is a heavy reliance on mechanisms that displace the burden of action somewhere else so carbon offsets are the primary mechanism by which this is done the theory perfectly sound from a climate perspective if it's cheaper for somebody else to cut their emissions somewhere else or to remove carbon somewhere else let them do that pay them for it take the credit and impose lower costs on your domestic interests the problem is that in every single compliance program the demand for these offsets comes from the incumbent industries who to be perfectly honest don't care about the quality of the offsets they want high volumes of low prices because they're trying to get that that simple compliance pathway a lot of the ngos you would hope would be standing up to monitor quality in these programs actually have a kind of perverse interest to capture the revenue stream that comes as private entities effectively buy their way out of the compliance option and often direct the the money and the investment to preferred outcomes in say forest conservation very famously the kyoto era offsets programs invested heavily in very questionable offsets with industrial gases and clean electricity more recently in the united states and in the voluntary markets that are scaling up in a world of net zero corporate pledges you're seeing some very suspicious claims being made on forest carbon and increasingly on soil carbon and we have a theory that we think explains why in compliance markets it's such a disastrous experience you want to move away from it as fast as possible so the last thing i want to say here is our theory of politics we hope allows us to explain four really important things one why do you get low prices and these potemkin market outcomes two why multi-sector programs although attractive with sort of economic theory become major political liabilities for people who have to hold together political coalitions third why the european example works they've instituted major reforms they cut off their offsets and they've driven prices up to the point where it's making a big difference in electricity but presenting a major challenge for industry and fourth why offsets have become essentially a nightmare for everybody who's used them and when we see people emerge from potemkin market outcomes it's usually because they cut back on offsets the last thing i want to say before handing the mic back to david is we also have some thoughts in the book about how to make markets work better the first recommendation follows from this this concept of veto points the smaller the coverage of the program the easier the ability to push the political stakeholders farther you'd rather have multiple programs we think than a single program that tries to put all these politics in a single game second recommendation is the more you can make markets like taxes the easier it is to essentially organize the politics around the beneficiaries on the revenue side and to make sure those who are experiencing political pain know what the upper limit on that pain is and the european experience and the east coast reggie program both give really great lessons on how to do this from a technical perspective and we think everybody including places like california need to think very carefully about those kinds of approaches third thing to say is that offsets really aren't working they haven't worked we don't think they ever will work you can replace them with the price controls you want by limiting prices you can direct the spending in the direction you want by directing the spending through competitive public programs and you don't have to assume perfection with these vastly complicated programs that are almost impossible to monitor fourth and final thing to say we talk a bit in the book about market links people have fetishized market links we think market links are perfectly good when you've figured out how to run a system the way you want it and when you create potemkin systems and start linking them together you put everybody into that low gear system and make it very difficult to reform so with that let me turn it over to david to close it out and i'm very much looking forward to joe and suzi's thoughts so well thank thank you very much danny and i just want to say one thing at the very end here which is um you can one can make markets perform better in a way that's much more attentive to the political economy and that's the argument that danny just summarized that we have a whole chapter about that in the book uh part of that is also frankly doing a better job with the way the money that's raised in these markets gets spent there's a tendency to to set that aside and really focus on the the effect of the prices on the behavior firms but if you think prices are going to be lower than what society is really willing to pay then the price effect is not unimportant but it's also what you do with the revenues that get raised and all this points just us in the direction of what might be called industrial policy not there's a key word here missing on the slide not just carbon prices not just carb not just market instruments but complementary approaches where frankly the industrial policy does more of the heavy lifting not because that's necessarily plan a if you think about this optimally but because it's planned feasible when you think about this this politically we have a lot of ideas in the book about how to make industrial policy more effective how the government can intervene in economies in ways that are less distortionary uh more effective in pushing boundaries and we may want to talk some about that today but i think the bulk of the debate today is about what's what's really happening with carbon pricing and we've laid out an argument why when you think about this politically you should be a little more suspicious so thank you very much and look forward to the discussions with joe and suzi uh thank you very much david and danny that was a very interesting presentation and now we have commentary and response by susie kerr and joseph majkut so suzi kerr is the chief economist at environmental defense fund she graduated from harvard university in 1995 with a phd in economics in 2018 she was president of the australasian agricultural and resource economic society her research work focuses on on domestic and international climate change mitigation policy with special emphasis on emissions pricing and land related emissions and sequestration uh joseph majkut is director of climate policy at the niskanen center he is an expert on in climate science climate policy and risk and uncertainty he also phd from princeton university and in atmospheric and oceanic sciences so i think suzi is going to start and then joe is going to follow good afternoon i think you've got the order reversed i'm going to lead off and then uh hopefully i can get us on first base and suzi can knock me out uh thank you to our uh speakers i really enjoyed this book um i uh while i play mr necessary and sufficient uh on the internet i think that the criticisms that you've raised and the empirical reality for how well we've been able to institute carbon pricing in the united states really has to be dealt with not just in the united states excuse me around the world um we need to confront the challenges that we've found uh many people have found them through decades of of hard work advocating for these policies or trying to design them and think carefully about how to make them better so i look forward to a productive discussion i'm now going to switch to my slides and offer a few thoughts on uh on the book and what we might be able to learn from it as as advocates by way of introduction the niskanen center is a 501c3 organization located in washington dc and we advocate for a carbon price as the principal means of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the united states i think it's important to remind ourselves of the basic case for why a carbon price as a policy intent on bringing us to net zero is an important one to make work well and why i think we should favor it as implementing one early as opposed to late principally the case here is efficiency we need to reduce emissions quickly and we know that that's not necessarily going to be a cost-free process in particular uh jesse and and his colleagues at princeton estimate that the energy cost increase associated above reference with a net zero economy is one to three percent of gdp those are very large numbers this is going to take large investments and so the more we can do it we can uh create policies that will be efficient that will work well the more we're going to realize public benefits and i think there's a real tension between the sort of political economy arguments that are being made um and and and hold some water by um by by david and danny and the need for public policy to to um achieve the best public benefit that it can i'm particularly interested in um the the you know the two principal things that uh carbon pricing drives both conservation and innovation we know that higher prices encourage conservation and i think one of the things that we can pin for later is a discussion around what's their role in driving innovation i have no fundamental opposition to industrial policy but one of the cases for carbon pricing is that prices are an important part of creating economic opportunity relative prices are an important part of creating economic opportunity for the innovators of a low-carbon economy i also will admit however that the industrial policy is probably something we should think more carefully about and it can be really important to the politics of transition in our work in the at the federal policy level we've seen uh particularly republicans historically um hesitant to embrace climate action have embraced clean energy as it gets bigger in their states that story is pretty straightforward to tell the picture that we see here shows us results from a study from columbia university and others that was released last year that i think is helpful in setting the tone if we want to have a net zero economy what is the carbon price we would need to reduce emissions to capture conservation emissions or emissions reductions and induce innovation for the long term this model it's a model-based study but they find that the prices we need are somewhere in the range of 50 to 100 dollars per ton over the next decade and i think those are actually the prices that we can talk about realistically not from the past decade and a half but for the one going forward uh the black bars here show you um the those carbon prices that have been introduced in congress whether we could get those bills to pass is a question but we are talking about what i think are net zero appropriate targets here oh how do i move my side forward there we go um i also think that as intentions for climate change get more serious we will see more serious prices as danny as danny mentions the european union has been making reforms and changed its goals for for emissions reductions leading up to 2030 price forecasts have gone up likewise we've seen in canada the embrace of a fairly ambitious increase in their carbon price federal carbon pricing program and that one uh revenue is primarily slated for rebates back to the population um and i would expect if that policy holds that you know by the end of the decade it's just a normal part of the canadian tax system and and um most households are are being made whole next slide one of the keys in the book that i think we we need to spend a little bit of time on is thinking about carbon prices or carbon markets as things that can work in the national interest that this sort of top-down picture of setting global goals and then designing marketplaces early that can help us accomplish uh those global goals has struggled to be realized in in real politics and so when we're thinking about how do we design things for the national interest and particularly in iscan and how do we design a carbon taxation system that can be sold in the national interest and then export it abroad we find that the carbon tax as has two key elements that i think are are underdeveloped in the discussion so far today one is that raising a carbon tax does create opportunities to achieve partisan priorities in the united states the u.s spends a lot of money compared to what it brings in in terms of revenue and that's that is a precondition that was a condition before we had uh coveted relief spending so and over the next decade we expect taxes to go up both on investment and income the way i would think about this right now is um you know with uh with a democratic uh senate and house and presidency that talk about budget reconciliation in the house or or in congress there is real political opportunity to create carbon pricing and achieve ends the democrats might want to seek whether that's infrastructure spending or or other sort of distributional programs child tax credits poverty relief etc we also know that border adjustments while difficult to perhaps set up and administer would if they were done correctly create competitive advantage for some domestic industries in the united states u.s steel is cleaner than our competitors this graphic here shows us emissions intensity of european imported steel and it was created by the boston consultant group as they were thinking through the business connotations the market connotations of of the eu levying a border fee on its own imports and you see down in the lower left there us carbon intensity of steel is much lower and i think more markets that uh would be carbon aware would uh help us um would help certain industries in the united states there's also a disadvantage for russian oil and gas production that we probably shouldn't leave on the on the table and lastly uh on the regulation bit uh moving quickly to respecting my time um administrative procedure in the united states is clunky and slow the book argues that we're better now the regulations that we have now the regulatory states we have now are better than those of the 60s and 70s they learn they're adaptable but that process is very very slow and if we think about trying to achieve climate targets over the next decade or the next two decades i think we can look at the obama clean power plan which was agreed to the epa agreed to rulemaking in 2010 proposed a rule in 2014 finalized it in 2015 lost in the supreme court in 2016 changes in administrations delayed action for another four years and if you look at a serious alternative to a federal carbon tax something like the clean future act which was just introduced in the house of representatives it requires at least 22 agency rulemakings within the first two years of enactment that are not quite as large as something like the clean power plan but would be onerous and and relying on a industrial policy and regulation approach which is kind of what we have today leaves there are huge opportunities for state industry and administrative delays with that i close i thank our authors and i look forward to suzi's comments i will run your slides thank you so danny david thank you jesse bob and others for inviting me to participate today um i also read the book again um and i ferociously agree with much of the material in the book the need for long-term vision about where we're going for experimentation and for strategic leadership that inspires and supports the followers shift changing climate change is like shifting a complex dynamic system into a new equilibrium that's a really daunting task and it's not something we're going to achieve simply with linear thinking we need to plan and the net zero america work is a nice example of that we need to motivate people we need to reassure people about the changes and we need to build trust that we can work together on this um i worry about some of the messages that could be taken out of the book particularly about carbon pricing and the way carbon pricing can play a role within the effort we've seen a lot of simplistic stories over the years about which policy instrument is best and those simplistic stories uh particularly when applied in a generic way can be very dangerous we've seen the tax versus ets debate which has not been a useful one for moving policy forward we need a portfolio of policies and actions and we should be arguing yes and lots of good policies there will be some overlap there will be some mistakes but but we need to be given the urgency of the problem we need to be dealing with a wide range of possibilities and every country is different every country is different in the sort of policies they will need because their economies are different their capability is different and their politics is different so things that won't work politically in the united states may work very well in some other countries it's very easy to criticize and economists are particularly good at this we have endless papers that show how particular regulatory interventions are ineffective they need to rebound they're not having the effects that are anticipated it's really hard to create effective policy so we do have uh some evidence some significant evidence that prices can be effective and by effective i don't mean they solve the whole problem but that they do help and they make change in the right directions we probably have less evidence of that on industrial policy and by that i don't mean that we shouldn't do industrial policy work hard on it but we shouldn't rely on it industrial policies are also enormously subject to political pressures that can make them less effective and in many countries the administrative capability to implement those will also be terrifically challenging next slide please so um cap and trade can play a really critical role and there are two particular ways that i think are important here one is that there are no other policies in our toolbox that can apply an enforceable limit across a wide set of sources and the new zealand case shows that that can be up to nearly 100 of emissions in a country so why does it matter that we are able to put on our enforceable limit the first one is that it allows us to create a backstop for other policies and this is the way i think it has been used in california it makes sure that the package as a whole actually does add up to the goals if the emotions trading system cap is set in a way that is consistent with those goals and it addresses problems like rebound or over optimism about the likely effects of policies and policy interactions it also is really valuable in facilitating credible international developments if you have a solid well-designed emissions trading system that covers a large part of your economy and then you make a targe a commitment in a united nations agreement then as long as you translate that through to your emissions trading system your cap and trade by an adjustment of the of the caps over time people can see that you actually have the ability to to comply with that and that you've made a visible legal commitment to do so it's also potentially a very valuable tool for facilitating international transfers that have high integrity i agree with david and danny that offsets have real problems they have right from the very beginning and i've never been a fan but we do need situations we do need the ability to reward some activities that are not easily included in regulation or in in standard pricing systems and most importantly we do need the ability to transfer resources and help and investment to developing countries who are just not going to go fast enough even if they take on 2050 or 2016 net zero commitments we need them to be able to move faster and if they have credible enforceable limits on their emissions that can be the basis for high integrity transfers also we know that price signals really matter that and they matter partly well very heavily as investment signals the most important thing out of an emotions trading system is not the effect on current behavior but the effect on investment there are signal one among many signals to investors of how serious society actually is about addressing this problem so that's that's a useful role to have and in in reverse the price and emissions trading system tells us what investors think about the likely future intensive that regulation because it's telling how much they're willing to invest in buying allowances and banking them for the future also we've tended to present emotions pricing as though it's providing an incentive for people to do something they didn't want to do but i think that it's really shifted a lot in the last five or ten years there's a lot of companies now who are showing that they are willing to act but the prices in the economic environment can fight against them because it puts acting and incurring costs puts them at a competitive disadvantage so including carbon pricing will enable those companies to do the mitigation that they are willing to do without loss of profit it also critically supports mitigation by all actors and we tend to focus on some of the largest actors in the economy that makes a lot of sense in many ways but there's a large number of actors that are small but cumulatively add up cumulatively add up to really a large group so next slide please the emissions trading system that i've been most involved with is is the new zealand emotions trading system and because new zealand is so small the only real impact that our policies have on global climate change is through exactly the sort of experimentation and enabling and inspiring that dave and danny call inspiring followership so new zealand is a country also where complex policy is difficult to implement it's not that we're not capable but there are very few of us so our experimentation has largely focused on emissions trading which is actually a relatively simple policy to implement relative to industrial policy which we did actually try previously our experience in new zealand really reinforces message that good policy takes time it's not something that you can create and then evaluate a few years later and say whether it's working or not it is going to evolve you're going to have to iterate and approve it over time when we don't have time that's hard to accept but we are doing better at managing these systems over time we've learned a lot so we're creating stable institutions new zealand has a climate commission the eu has much better institutions managing its carbon pricing and as those institutions get stronger the prices are getting higher we're getting better at managing prices and in quantities within those systems and that's largely in my mind nullifying the debate between carbon taxes and carbon pricing and we're beginning to seriously reassess the high levels of free allocation i would say new zealand has very low levels of free allocation but but most countries do have high levels and we're refocusing on how we can use that revenue next slide please so please don't make acts with our future we need to invest in a portfolio we need to be working on a wide range of fronts a wide range of different sorts of instruments and we do need instruments that will keep us honest and that's where an enforceable limit can be terrifically helpful thank you thank you very much both both sets of panelists for a very interesting beginning to our conversation i'm going to ask one question and then turn the questions from the audience and the question is this there are two points of agreement between the two teams here you agree that carbon prices can be good policy very efficient and if you can get a carbon policy if if a divinity could impose the carbon policy on us you probably all all four agree that it should be done um you also agree that government policies as david and danny have shown in the last decade have been way too low to accomplish very much uh what i want to ask david and danny first and then joe and suzi is what political processes can be realistically imagined during the next decade that could generate a sufficiently high carbon price let us say 1500 a ton that would make it that would make a genuine difference as the eu has started to move toward but david do you want to start yeah maybe i'll start there um and i think you've summarized the areas of agreement you know we have disagreement about how big the portfolio is in different areas and so on we have violent agreement about the theory of using markets the place to look where you can really do the most with carbon pricing is in the sectors where you can manage the consequential politics of that most readily and so we see that in the power sector um so you could you could make quite a lot of progress uh and indeed that is the european experience now uh make quite a lot of progress bringing up prices in the power sector managing through tariff control and so on the other consequences of that it's literally literally bolted to the ground so it's not going to be migrating to another country to escape regulation and not going to be competing we're not competing with electric generators in russia and and so that's the place that in some sense i thought that i think that's going to be the high water mark suzi or joe so i'll just throw in a couple of thoughts and one is building um bipartisan institutions and i know this is terrifically difficult in the u.s but i think it's something that other countries have managed to achieve and can manage to achieve and de-politicizing that that carbon price so that it becomes a financial issue it becomes something that's about the treasury and not about the ministries for environment etc i think can be very helpful um and i think our experience has certainly shown that um i think the other thing is as david and danny's policies are successful in building up new sectors or if you include sectors that are inevitably on the winning side of prices you're going to be building those constituencies for high prices and in new zealand it's been really critical that we include forestry not as really offsets but as a as an integral part of the emissions trading system and foresters uh win out of the system so they have been a critical lobby group for getting higher prices and better price control okay let me pick up on the bipartisan point there are a couple of questions uh from from the attendees which focus on uh either on on two questions both of which have to do with bipartisanship one is industry including big oil firms uh has to some extent supported a carbon tax as david or i think it was david said uh provided that there be uh some sort of regulatory rollback uh i want to know i think our our attendees want to know whether this is a faint or whether it's genuine support would they be would they actually form a basis for a coalition with real estate compromise or would they say oh no sorry you didn't take you didn't roll back all those regulations we don't like and therefore we're not supporting it and this relates to a question by an attendee who's anonymous asking how we'd how you'd assess the prospect for fee and dividend programs like the citizens climate lobby bill closely related uh would the direct cash payments change the politics or would that be turned turned on its head once it was a serious proposal so i'm trying to start with with with david or danny again and then i'll come to joe or suzi sure so i mean i think the question of regulatory rollbacks is one of the toughest and it's something i can't sit here and say with what the american petroleum institute's actually going to demand as part of these negotiations but i think there's a pretty long history of there being some questions around both the sincerity of those efforts and the scope of what's desired as a compromise and i'll point to you there's there's no greater example of this than in california where the oil industry demanded massive regulatory rollbacks that took away the climate regulators ability to set direct regulations on either our refining industry or our upstream oil and gas industry period end lost all regulatory authority on that industry hopefully we're going to get that back but that was a precondition of the extension of the cap and trade program to isolate a price that did very little to affect those sectors and i think the national industry is probably thinking on similar strategic terms if we got to a real negotiation around this i think this question of what the rollback would be has got to be front and center in the conversation and half promises and illusions and vague statements make me very concerned about the direction that conversation would head in but i can't tell you it's resolved because nobody's saying anything concrete that has real political muscle right now second thing i want to say just to touch briefly on the citizens climate lobby point the the problem that we're trying to address is transportation fuel prices are visible and toxic and a dividend is a solution to that on paper i love it i think it's a great policy i even helped write a bill in california to do just that the problem is there isn't much of a serious constituency for that beyond the educated activist community and when you start to get into real conversations around billions of dollars lots of other hands come into that pie and start taking away from it if you could get it i think it could potentially help address these concerns but we need to watch right now that conversation unfolding in saskatchewan and alberta and canada where the federal government has said this is what we're going to do and if you believe that this theory is going to address the political problem i've identified watch how conservative parts of canada react to those ideas so far it's not looking particularly good even though i will tell you as an economist you pencil the numbers out it is absolutely a progressive policy it's not clear to me that that resolves the political problem that it&

2021-03-26