Building Green New Advances in Sustainable Homes

Hello, everyone, and welcome to ACS Webinars, connecting you with the best and brightest minds in chemistry and other sciences, live from Washington DC. I'm Michael David, and I will be your host for today's broadcast, which we are proudly co-producing with the Science History Institute. Today, we will be joined by a panel of entrepreneurs, architects, and engineers, as they present advances in sustainable use of resources in residential housing that can be applied to both existing and new residential dwellings. And now, I'm going to turn the program over to Lisa A Grissom, who is the senior philanthropy advisor at the Science History Institute. Thank you, Mike. Welcome to the Science History Institute in Philadelphia and to our Joseph Priestley Society Series.

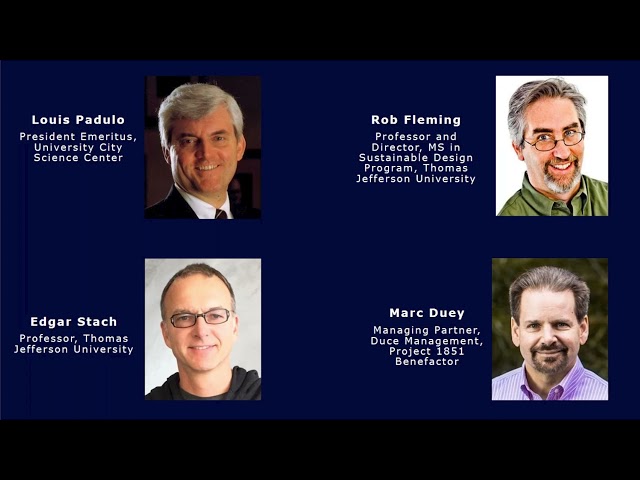

We are delighted to be co-producing with the ACS Webinars, and we will be taking questions at the end of the panel discussion. It's my pleasure today to introduce our panelists who will be anchoring the program. We have Louis Padulo, President Emeritus, University City Science Center in Philadelphia, who will be the panel moderator, Rob Fleming, professor and director of the Sustainable Design Program in the College of Architecture and the Built Environment at Thomas Jefferson University, Edgar Stach, licensed architect and professor in the College of Architecture and the Built Environment at Thomas Jefferson university, Marc Duey, managing partner, Duce Management and leader of Project 1851, the building of a tech integrated and regenerative rental property, and Daryl Boudreaux, physicist, and member of the Joseph Priestley Society Executive Committee, who will lead the Q&A at the end of the program. I'll now turn the program over to Louis to further introduce the speakers and lead the introduction.

Since um, we're sponsored by the Science History Institute and the American Chemical Society, I thought I'd give a little bit of a history. I'm a... I was an electrical engineering, I was an electrical engineering professor at Stanford then became Dean of Engineering at Boston university, then I was president of the university of Alabama in Huntsville, and then I got to be the CEO of the University City Science Center, which is the world's first business incubator, where with the Ben Franklin program that we started, we helped people start companies, mostly science technology companies. And I didn't have a heck of a lot to do with the environment.

Um, I met Marc Duey, um, who's on the panel today, uh, because we were both on boards of directors. We were both directors of, uh, high tech companies, mostly biotech type companies. And at one point, um, Marc, um, showed me his house, uh, which was an old farm.

And I saw that not only did he have a grand, uh, way to live, but he tried to maintain the, at least the vestiges of gentlemen farming. Now, um, I mean he had, he had livestock, he had horses, he had a daughter who became a veterinarian, uh, specializing in large animals, ma- mainly horses. Um, at one point, um, I got invited... Uh, I got cancer, so I retired from the science center quite early. I'm still alive, I still have cancer, but I'm still around, and then I started teaching again. I started teaching product design.

I did it for about 10 years at Wharton. And then out of the blue, I got asked to be the founding dean of the College of Architecture and the Built Environment at Philadelphia University, which is now part of Thomas Jefferson university. Um, at that time, um, one of the programs that we had, my, my mission was to get us reaccredited in architecture, to set up the structure of this new college that I was the executive Dean of, and to, uh, have the search for a real permanent dean succeed.

Um, all of that worked out really well. One of my star programs there that I inherited and get in good place was run by Rob Fleming who's one of the speakers today. Rob, uh, had a program in sustainability. Well educated as an architect and practicing as an architect, he latched onto sustainability as his mission in life, and he was a missionary about it. He was the first friend of mine that had that as his primary, uh, activity.

And most of the courses that he taught were part time to existing architects and people in the region. Um, while I was there, um, I got to meet Edgar Stach. Edgar Stach was... one of the other panelists, uh, was a professor. Uh, we, to be honest with you, we, we got a wonderful deal. We hired Edgar and his wife.

His wife, Barbara Klinkhammer was named the Dean to be the real Dean of the college, I was leading, CABE, College of Architecture and the Built Environment. Edgar was a distinguished professor of architecture at University of Tennessee and had a joint appointment with the Oak Ridge National Laboratory where he worked on really high tech aspects, they say material science and electronics and instrumentation, which was unusual for architects. During that year when I was running the college, um, I invited Marc and his wife to come out to the various show and tell periods when students would be showing their work. And Marc and his wife really got interested in a lot of the design that they saw.

In fact they hired several of the students there to work on various projects. Among the projects that Marc worked on, uh, one turned out to be a real challenge and he came to me later on, because we remained friends, he came... and still on a couple boards together. He came to me with this idea that he wanted to do a real sort of showcase on how you could live well in a sustainable way and cherish environment, not damage it.

And so he wanted to take a challenging environmental, um, area, namely one that was under the flood plain and maybe on the banks of his beautiful stream and, and see how he might have sort of an, an eco experience, uh, building whereby he could train people, maybe executives, or maybe just students are bringing out there for a retreat where they learn how to coexist with nature, using appropriate technology when necessary to not mess anything up. Um, with that in mind, um, he asked me for help. Did I know anyone? So I just told you the history, since this is the history. Now I'm gonna tell you the chemistry. I'm not a contributor here, I'm just a catalyst, but if there's one place on the planet that a catalyst would be appreciated, it's the American Chemical Society. So as a catalyst, I pulled together these pe- these people, Rob Fleming and Edgar Stach to work with Marc.

Meanwhile, Marc met Darryl Boudreaux of the Science History Institute, and Daryl was looking to put programs together, and Marc said, "Why don't you put a program together about sustainability in residences? Nevermind things like the Comcast Tower and people with green roofs on colleges, but people who have residences and where they want to live in, in constants with nature." So that's how this program started. Now with all that, as a background, I told you, um, we're gonna go right into the presentations. The first person I want to speak is Rob. Now, Rob Fleming, I mentioned to you was an architect.

When he and I were at Philly U and I was promoting him as one of my stars to show off to the world, that's what you do if you're a, a promoter, um, our boss who was then the president, a former businessman said to the two of us, he said, "Hey, it's really cool that you're showcasing Rob with this sustainability but have you given any thought to the fact that that's a popular flash in the pan, and pretty soon everybody's gonna do it. Now, when everybody's doing it, what are you gonna have to brag about?" And we just, we admitted, we hadn't thought of that, that I have to say to our sorrow, that hasn't happened yet. [laughs]. The world has not all caught on and sustainability is so second nature to everyone that Rob Fleming still has a perfectly good living ahead of him for many more years.

And he's published widely on it, and you'll see links later and he'll post links to some of the seminars and some of the free, uh, videos that he's put together to give you the background on the whole notion of sustainability. So Rob is gonna set the stage for us today, and then we'll move on to the next speaker, which will be Edgar who'll talk about technology, and then we'll go on with Marc, which we'll talk about essentially the challenge that we're all facing. Well, thank you, Louis.

I appreciate the opportunity, and in fact, I am about to celebrate my 25th year of sustainability education so I hope you'll all be there for the party. In 2005, a series of events occurred that radically and fundamentally reshaped our relationship to the natural world. It was a time when we finally began to realize that our CO2 admissions would in fact have devastating consequences on our environment and on our way of life. And over the years, we saw more and more disasters happening with greater frequency and with greater impact. And by 2020, I think we all can now begin to agree that this has become one of the existential crises of our time.

And I think you would all agree that we need to change and we need to change fast. Albert Einstein said, "you can never solve a problem on the level on which it was created," and today I'm gonna argue that we need to go on to the next level and the panelist you'll see after me are doing exactly that. But first I think we need to step back and think about the way we think.

And I think this is why Louis it's taken 25 years for us to get to this point, because we're still thinking in the old way. And the first part of doing a net zero energy building, which I'll explain in a minute is actually changing the way you think. It's very difficult to try to do a net zero building with standard architectural design approaches. And then furthermore, deep down, you've gotta change your sense of purpose.

What is the reason that you're on the planet? Why are you here and what role do you have to play in solving one of the greatest challenges of our lifetime? When you do that, your words change and your meetings change, and the kind of definitions change, and the words like net zero or carbon negative become part of your vocabulary, and as that happens, it becomes more ingrained in the mission of your life. And then ultimately you'll begin to collaborate differently, you'll begin to work with people that you never thought possible. So for example, I work with biologists all the time to talk about toxicity of buildings.

I work with engineers to talk about how to make PV panels more efficient. I work with clients like Marc Duey on how to do a better building. And those collaborations require us to be able to think outside of our discipline and keep our eye on the prize of what's really at stake. Eventually, we start to make better choices. We start to decide to become sustainable. And ultimately we become leaders.

When we're doing sustainability, when we're moving these initiatives forward, we're actually leading in the spirit of what humanity needs for us in the 21st century. So this happens to be a net zero building that I worked on a few years ago at Revision Architecture. You'll notice that there's a lot of roof dedicated to solar, you'll notice that the building is in harmony with the environment, you'll notice that there's all kinds of special technologies happening in here, which we'll hear more about later, but how do we get to that net zero building? What were some of the steps that we had to do in order to achieve this? So we first had to agree on a definition, a zero energy building produces enough renewable energy to meet its own annual energy consumption requirements. This is going to become the standard building code within 10 years in Europe and within 15 years in the United States.

We are moving to a net zero base economy. The cars that you drive, the buildings you live in, the products that you use will ultimately have a net zero impact on the environment, and then we'll begin to reshape our carbon emissions and how we can begin to really make the changes that we need. So, I like to focus on principles.

The other panelists are gonna really dig into the details of net zero, but today I wanna just start you off with some principles. How do you think about net zero? And the first thing you do is you consider all of your options. Should you build new in a city? Should you renovate? Should you build green out in the middle of a wonderful environment? These are questions that have to be carefully considered.

Where we build and how we build as an... a tremendous impact on our carbon footprint. Then we wanna consider future adaptability.

It's not just designing a house for now that works for the family as is, but what is a building look like that lasts for hundreds of years? And one of the things you wanna do is think about how our needs will change. And certainly during the pandemic of all times, we've seen how radically our lives can change so quickly and good net zero architecture is gonna consider flexibility to make the building last longer. And then we're going to go in and use all of these amazing passive design approaches, things that we've known for centuries, and we've sort of forgotten in our alliance with technology and now we're rediscovering. The way a building faces the sun or doesn't face the sun has a large impact on the energy footprint of a building, not to mention our own comfort inside the building.

So we wanna max out all of our passive technologies because we do those Watts. We put a shading device on a building, we do that once and we have it for years and years and years and years. These are passive technologies that are really critical. And then even before we get to tech, we got to look at the envelope. Air is moving inside and outside of your building at rates that are really causing you to use a lot of heating and cooling for your houses and therefore emitting lots of CO2 into the atmosphere. And if we can rethink our building envelope, make them tight, make them efficient, we're gonna see tremendous savings and tremendous environmental improvement.

And only then after we've done all of this do we start to talk about all the cool tech, the HVAC systems, the water reclamation systems, all those kind of heating and cooling things that we love to talk about and think about, um, but really those come very much at the end, uh, before... after we've done all of these other things that are so important. And finally, at the end, if we do everything right, the number of solar panels that we need to actually get to net zero is very small. And this is really the, the crux of being a net zero energy designers, is to try to think through this pyramid and make the kind of changes to the way you design so that we can all benefit in the future.

Thank you very much. We'll come back with Q&A, a little later, but first we're gonna have the initial presentations, and Edgar Stach, please tell us what you do. Thank you for the introduction. So I think, um, I think you will probably open up to floor up if we're talking about sustainability in a, in a broader sense. So sustainability is a, a net zero, really goes from urban scale to building scale to a device scale. And I wanna present here quickly, um, not only a zero energy building, but an energy plus building.

So this was a prototype of building built at the University of Tennessee, was, um, in collaboration with Oak Ridge National Laboratories. And it's really sort of a mini, uh, test batch to, to showcase, um, what is possible today to really move forward, um, with energy recovery and technology. So this is really a sort of a, a laboratory building which has two cores and a glass envelope all the way around.

It's really meant to be a small, um, you know, you know, starter home or a unit which can be stackable. So just a few images, um, here, you can also see already is affordable, takes out technology loading as a, uh, sort of scaffolding about the building. It's a squeaky-clean glass envelope on both sides. Um, some on the interior shots. So what you see here is, uh, the building has LED lighting into floor and ceiling, has a super tight building envelope, has a quadruple glass pane, uh, system, uh, operable windows for natural ventilation and, um, certainly shading devices.

And I'll talk a little bit more about the complex envelope system in a second. So this a little bit of a, um, introduction into the flowchart houses building, uh, incorporates for the [inaudible 00:17:28], cell technology, um, ventilation system for the entire house, a heat pump for heat recovery and the, the entire makeup where everything sort of works with each other to, um, be most efficient in terms of energy usage, but also using the natural resources as much as possible. So the whole house was powered by a 10 KW photovoltaic cell system, and these cells are cylindrical. It's a company once Solyndra, unfortunately when uh, underwater a couple of years ago. Also, um, we use these, uh, cylinder photovoltaic cells as a shading device, also for the facade. The façade themself, um, has two layers and about a, a foot of space in between and this, um, um, these two layers and in a quadruple glass layer and an older single glass layer, and the space in between really works as a greenhouse or buffer zone.

So passive heating and cooling could be achieved through the facade. And then, uh, finally the façade then was also linked to an air conditioning system or ventilation system. So the passively warm air can be used inside the building for heating or cooling the building. Um, we also use the systems like energy or energy recovery ventilators, which is a device, which you ventilate your house in winter or summer, and you would cover the energy embedded into the air. In summer you keep the cold air inside and in summer, so you're, you're ventilating in a way that you're not losing by ventilating energy embedded into the air. So what does that actually mean in terms of, uh, savings? So, um, with technologies like energy recovery, uh, tight building envelope, um, good insulation, um, this house used, uh, only half the energy like a top notch house built today.

So it's a huge energy savings and this here uh, large photovoltaic, system on the roof, at the end of the year you actually make money by using that technology. So the the complexity is really in controlling all these mechanisms like the photovoltaic cells, the ventilation systems, the blinds and so forth. So you need a control system to, to monitor things and control these, and for example, the blinds, so this a graph showing that blinds are really important, but if you have blinds, they need to be outside the building or outside the envelope otherwise a, a counterproductive, but coming back to the control mechanism, so if you have all these complex systems in place, you need a dashboard and an easy way to set temperatures, um, the ven- the ventilation modes, and so forth, but we also developed a system which at the same time looks into different lighting schemes, um, modes, you can control the media, you can attract the energy flow and the weather. Uh, because the building we developed also was, uh, sort of [inaudible 00:20:51], it was a battery pack system, so we'll see photovoltaic cells on the roof, we can also power power, power an electric car, an EVlink, uh, car, um, we'll see excess energy, and in times when the battery pack in the house was running low, we could use the battery pack on the car to power the house.

So energy was flowing back and forth between the building and the car. And, uh, because this building was meant to be a showcase or movable laboratory, so, um, it was uh, build on a sort of a steel chassis system, which you can see here. And so...

And that house traveled to various, uh, locations to showcase the, the technology and really brings the technology to, you know, a typical American. And this was a way the house was transported and traveled through the country. And, um, this is the end of my presentation. Thank you [inaudible 00:21:53], thank you very much for your attention.

I should have pointed out that architects are generally not as tech savvy or in interested as Edgar Stach is. Architects are often thought of as designers and design usually connotes, um, artistic, and so for several famous architects for example, are more like sculptors. They'll make...

Think of, um, the first woman who won the Pulitzer prize, I'm blanking on her name, Zaha Hadid, I think, and then, um, Gary, they'll make some gorgeous thing out of paper mache and then turn it over to [laughing], their team and say, "Okay, make that into a building, make it work." So Edgar is really unusual in that he's an architect who really keeps up with the technology and wants to use appropriate technology. Now, ready for Marc Duey, who I told you was the, uh, in many ways, the o- originator of this, uh, this notion, and Marc's gonna tell us about this project which he gave a funny name to, Project 1851. We won't ask him about Project 1850, it probably turned out very successfully, but he'll tell us about Project 1851. Take it away, Marc Duey.

Thank you very much, Louis. It's a pleasure to be here this afternoon. It's very nice to spend time, uh, with with Louis and Robert, and Edgar, and I wanted to thank Darryl and Monica, uh, from the, uh, Science History Institute who helped a lot in the forming of the, uh, um, presentations that we have here today. Louis, uh, Project 1851, not 1850, not 1852, uh, for two reasons. Re- reason number one is that the address of the building lot that we've chosen for this project is actually 1851, uh, Art School Road, a very historic road In Chester Springs where both Washington and Lincoln used to, um, um, uh, walk on apparently. But 1851 also is a, a year in which a famous scientist in Paris, uh, Professor Foucault, um, um, did a demonstration project, a project where he decided to find a building, a very large, tall building in Paris, uh, one that once had royalty in it and, uh, and hung a very, uh, four-story pendulum and, uh, let it sway so people could see that the pendulum would move in a certain direction over time proving that against the current, uh, understanding of the day that the earth actually spins.

In the same notion, one of the things I try, I wanted to do, and, and we are now trying to do, uh, with a fully budgeted project and the help of smart people like Edgar and Robert, um, and, and the, uh, and, and the guidance of, uh, of my mentor Louis, uh, Dr. Padulo, to put together a project where we could be showing and demonstrating in practice, the current available technologies that can really make a difference and where people could consider building houses with these technologies in an integrated fashion, uh, rather than a one off fashion. And so what we wanted to do was to create this dwelling that would demonstrate these things all at one place and, uh, and be an icon or an example of stewardship and high performance building design, all in one place and be open, transparent, and have a lot of students from, uh, the, the institutions where for example I teach at Westchester University, able to come see and learn about both the fun part, which is seeing technologies work, and the hard part of, of, of, uh, making decisions and tradeoffs financially, staying within a budget, and, and, and also working with local authorities with the compliance and regulatory environment and dealing with the EPA on, for example, of all the way through to the kinds of waste management techniques that are accepted, and those that are on the verge of being accepted.

And so the idea from a visionary perspective is to, to work, uh, in an eco-friendly environment but still tech rich, where we understand the chemistry, understand the biology, understand the, the physics, um, to build a, a sustainable building using innovative ways of, of building and having a, a green, uh, existence. Climate change is such that, uh, there are some, um, um, municipalities, and even mayors at a recent national meeting where they're just considering, uh, giving up essentially on certain land and saying, "You know, we can't even make it resilient enough to manage the floods and the other kinds of the perturbations that are no doubt gonna come because of our current lack of international stewardship, uh, uh, around climate change. And I felt it was important to pick a piece of land that was not optimal, but actually one that was very challenged from a water and flood perspective, in other words, a subpar piece of land to be able to, um, uh, show that things can be done, uh, from a, both a regulatory and environmentally sound and technologically appropriate way, even in difficult environments. Um, so the idea is to use as a template so that other people could come in, learn about all the details, um, and, and, and even, um, use it for themselves, if you will, certain techniques and provide a roadmap, uh, for assembling the carbon negative dwelling.

And so the main approach of course, is to use solar, and so we're, we're, we're friendly with the, with the Tesla company. Uh, we wanna preserve and, and get points if you will, for collecting, uh, pieces of, of, uh, of, of, uh, construction materials from, from within a five and 10 mile radius of, of, of the building as much as possible to recycle materials. We've been so very fortunate to have already many donations, and, um, if you Google the Project 1851, you'll be able to provide also free, you know, uh, provide rather, um...

I'd like to think it might be free, but the materials to help us build a, uh, a... so that we don't have to construct, uh, and have factories be building things that, uh, that uh, take up a lot of energy. One example is Brandywine Realty in King of Prussia, was taking down a building, um, uh, recently, um, on, on American Avenue, in, uh, in near Allendale and they're busting windows, these large six foot by six foot, uh, double, uh, thermo double pane windows with some nice tints in them, and and they don't look over 100 of them. And, uh, we asked for permission to go in and, uh, and we did get permission, we, we went and pulled out and preserved, um, some 62 windows, a couple broke, we stored 56 windows, large windows for building, but not only this house, but also a greenhouse, uh, that will be adjacent to it. Water will be obtained through rain water using, using these very interesting, uh, water flowers and for waste management, we'll be doing composting. That way we will not be disturbing the land in this floodplain, um, uh, very much at all.

The location, this is now very practical, this is very, very real. Uh, it's a, it's a 1.1 acre site, uh, in Ches- in historic Chester Springs, um, and we are currently in the, uh, uh, stages of regulatory approval. The, the, um...

This is just the site plan here where the idea is to build a 2000 square foot, uh, building, uh, as well as an adjoining, uh, gym that will be creating energy because all the equipment in there will be, uh, creating electricity, uh, and then the greenhouse to minimize the amount of food that would be of course trucked in from possibly long, long, long distances. Um, this is an example of what it actually looks like. There's an actual stream, you can see at the... from, from the top left, going to the bottom right. This is the worst part of the year, this is, uh, in, in, in the wintertime, um, and, um, the, um, um, about 97% of this property, except where you might see that little car, you see one little car in there at the bottom left, and that's the part that's not in the flood plain. Um, but generally speaking, by the way, it's quite fine until, uh, until there's a big storm, in which case there's some, some water flowing through and so clearly the house will be on stilts and we'll have, um, uh, some, some nice views of the adjoining, um, uh, forest and, and interesting trees there, as well as a view of the, uh, of, of, of, of the Creek.

The, the, the, the key thing is that as a demonstration project, we wanna have a significant learning pallet and have the opportunity to experience and learn about sustainability in leadership, and of course, we're not leading, we're copying, or we're bringing into an integrative environment things that exist and have been designed in other places, but bringing them together to coexist and, and, and work together, uh, and I'm sure some things will work well and some might not work so well, and we'll be transparent about those, those things. Uh, but having a biophilic and advanced tech house design, um, where, where, where each and every time we learn about something new, we're trying to do it like an algebraic equation where we'll, uh, we're like in software, we have API APIs that you pull in and pull out, we'll, we'll try it to be able to design it for the future where as new technology comes online, becomes realistic and the... available we'll, we'll try to incorporate it.

But people can learn about real estate development in, in as well in, in, in challenged geographies, instead of running away fro- from these challenges. Uh, building green, uh, uh, is... so that every aspect of design in the building and the chemistry and biology is considered, so, so, so that the, um, impact on the environment today and impact on the environment in 20 years and impact on the environment in 50 years is, is considered.

Um, and then the construction management process itself changes as a function of the perspective that you have on the materials, and hence, to the degree they're recyclable, and of course the overall, uh, the greenhouse contributions, positive greenhouse contributions of having and growing, um, uh, food on a year round basis, um, nearby. So our aspirations are, you know, being, being a business person and, um, wanting to have KPIs, even going beyond those of educating, sharing, um, and communicating, uh, we want to have some aspirations that are, uh, somewhat business, more business related, and so the idea is to have it booked one year in advance, um, is a nonprofit activity, so it's not, not the financial component by any means, but to show that it was designed so well that people come stay for a couple of days and talk about it so much that the word of mouth, um, uh, uh, is, is very positive about living in a carbon negative, uh, off the grid kind of environment. Um, we'll be throwing in the Tesla car for people to borrow while they're, while they're staying there on the weekend. Um, and the idea too, is to have the design, so, so, uh, so we're finding ec- uh, exclusive, that individuals, uh, will wanna come from distances because, uh, our hope is that, and, and desire is to have it written up in Architectural Digest or an equivalent, um, communication vehicle, uh, of, of some repute, so that we have to...

when we consider each of the decisions that we're making, we're wanting, we're wanting to not make any compromises from design, uh, comfort, uh, et cetera, to be able to meet these, uh, important, um, KPIs. Um, um, this is just, uh, an email if you wanna get more information on it, as well as, um, anyone that wants to make... uh, has any questions or want to make, uh, contributions can go to the, uh, to our, to our website, to, you know, to do so. And we suggest that if you're interested in this journey, it's, it's really, uh, on its way, but still at the early stages of that.

Um, please, you know, come and provide ideas and also take away and pull away any, and all thoughts and ideas that we're, we're an open book and trying to educate and demonstrate like Dr. Foucault did, in 1851 to show that the earth was spinning. Today, our earth is challenged, and we need to be able to take entrepreneurial initiatives to show that, that we can be doing things differently and, and, and doing so with our, with our, our um, conviction and with our pocketbook. Uh, Louis, thank you very much. Thank you.

And now we'll have a conversation amongst ourselves. Um, you might, uh, I might ask Rob, that Rob many people in sustainability yourself included talk about the triple bottom line. Could you tell us what the triple bottom line, and then what your wrinkle on it? Rob is the person I heard say this really a fourth bottom line. So tell us, first of all, what do you mean by triple bottom line, and then tell us the fourth. Thanks Louis, this might help answer some of the questions in the chat box. There's a question about how we define sustainability.

There's a difference between sustainability as a broad concept and say sustainable development, which is very well defined at the United Nations, but we tend to use the term triple bottom line, people, profit, and planet, as a shorthand way to think about a project holistically so that social equity is, is reasoned in there, there's some interest in economics, and there's also some major environmental impacts. But being an architect and staying up all night, doing drawings for years, I wondered what role does beauty play in sustainability and sustainable development, if it's beautiful, is it sustainable? And I think this gets to this question also in the chat box about the spirituality and the higher level thinking. And so I would offer that sustainable design could be defined as the quadruple bottom line is people, profit, planet, and place. And the idea that your buildings and your initiatives fit into the environment that they are, they are meant to be in.

Marc, what's the most fun thing, uh, that you've been encountering in your projects, and what's, uh, the most, uh, vexing part of it. Oh, Louis, thanks. Thanks for asking. No doubt, the fun part is all the, uh, uh, commensurate reading and exposure and discussions with leading, uh, authorities in new technology, uh, whether it be in the electrical side or power side, or whether it be in the capture and recycling of water and cleaning of water, uh, side of the equation, or in waste management, you know, incineration and composting toilets, for example. Um, those are all real interesting. Without a doubt, though, uh, dealing with humans, dealing with constraints, and it's clear that the design of our, um, regulatory apparatus, if you will, uh, you know, both from the federal perspective, as well as right down to local township level, uh, while everyone is well meaning, they certainly, uh, don't make it easy for introducing new technologies, but that's okay, that's part of the learning process, and in fact, we'll need eventually some forms of, uh, I think, innovation, cultural, and, and, and regulatory innovation, to be able to, um, grease the skids a little bit for, for new technology so that we can achieve the kinds of green environments that we're, we're, we're heading towards.

I, I really like your presentation and I really like the, the way you described how important technology is, and what we can achieve, actually without even touching technology. You know, we, we have such discussion all the time that we really have to start with all the passive technologies we can use on the siding, all the additional stability, making sure that the building has proper insulation, uh, um, glass envelopes which are not leaking and if that is all exhausted, we're really moving forward and in fact some high tech features, which in most cases we probably even don't know, or maybe we don't have the money for that. So what's your take on technology versus proper planning? Is that, is that a question directed to me or to the more smarter professor Robert? [laughs]. Either, either is fine.

Okay. Oh, you want men to go ahead? Okay, well, I mean, uh, Edgar, I am, I'm a person that would like to use technology as the last resort. We have 12,000 years and more of examples of architecture where people have gained comfort without any use of electricity, fossil fuels, using only the sun and the breezes. So I tend to look at technology for me and I... by the way, I loved your tech, Edgar, in your presentation. I tend to think about technology as the last thing to think about is only after you've exhausted every possible vernacular, indigenous, or low tech option, and then jump into these really cool things that I love to get excited about.

That's just sort of my, my basic approach. No, I think you're absolutely right. Even, even, um, with the building, I, I showcased, it was sort of loaded with high tech, but it was also sort of a spaceship.

So, you know, the thing, testing how far can you push it, and then you have to trickle back to a normal setting and to basically have to bring it back to something which is also affordable. You know, at some point, you, you will spend our money for very little gain, and I think you're right. So in, in, in general proper planning can do a lot with, you know, you know, basically the same amount of money you would also use for not proper plan.

And I think [crosstalk 00:39:23], that's sort of what, what you're getting to that you're not exhausting, you know, every single technology. You really wanna make sure you're, you're building siding, correctly, the orientation to the sun is proper, you have a proper building envelope design and insulation, and so forth. I think that, that's really the very first step in sustainable design. Yeah, I think also what is, uh, one of the things that Robert pointed out, which, um, I like a lot is the importance of collaborating in new and different ways to bring technology and/or solutions, lower tech solutions. In discussions just last week with, uh, with Steven Foley, one of the architects that's helping us, uh, you know, he sat and he looked at the, at the Creek that's nearby.

And of course, you know, technology person says, "Oh, let's put something in the Creek that turns around and make some energy." And, and he thought that, you know, you know, for hundreds of years, people use creeks for a number of things, including cooling. And I thought, Edgar, I will make sure I mentioned this to you because, uh, he's currently designing a way to get the Creek to come in to the house so that some of the water is moving throughout the house so that it will be an actual way to cool the house as well, as well as, uh, hydrate, you know, rooms to a certain level.

Um, and, um, that makes... it's a good example of, of, of a relatively low tech, uh, way to, to save money and to, uh, and to live a little bit like the people did a long time ago. Well, one of the technologies, I, I think, uh, we all can embed easily in, in our houses is really, um, the, um, energy recovery ventilator I mentioned before. It's actually a very affordable device which helps you to bring in fresh air without losing all the energy by opening the window, you know? At winter, you lose all the heat and at summer you lose all the cool air. So that is sort of high tech, but it isn't high tech. It's really something you just plug into the wall or, um, as part of your air conditioning unit.

And there are actually quite a few technologies that are out there. You know, we can embed in a lot of houses or retrofit in, in, in our houses easily. Louis, may I- Yes please. ... ask a couple of questions that I've notice some of the people from the audience asked. Uh, one that intrigues me relative to some of the other things that you have all said is someone asked, and, and Rob, you might be the one to kick this off the answer to this, what are some feasible cost-effective renovations that can make an impact on older homes and apartment buildings? Wow, we go right to the challenging technical questions. And in many cases, Daryl, we have to get behind the walls and see what's behind that drywall or plaster.

Older houses were built at a time when heating energy was very cheap and so there wasn't a lot of emphasis on installation and there really wasn't a lot of technology. And so, um, the, the hard way is to get inside the walls and think about actually reinsulating your house. This is what we call an [inaudible 00:42:24].

They do this in Germany a lot, they call this deep retrofits. It's one thing to go with caulk around your windows, that's gonna be a good thing, Darryl, but if we can begin to think about really looking at the entire envelope, that's the walls, and then of course the windows would have to be replaced. And many times they don't meet historic standards, hence the challenge, and then we lose our heat through the roof.

Any crack in your insulation, in your roof, wastes, wastes, all of that energy that you spent to heat, heat, your building. I would urge the, uh, the viewer to look at something called deep retrofits. It's something that's gonna be coming to the US in a very big way, and I think it's time to embrace that as much as possible. So what, what I would actually always suggest is buying a really, really cheap thermal camera which can be attached to your smartphone and then really look at, from inside and outside what the temperature gradients are. Where...

You see immediately where cold air comes in and that's your target. You have to get... You have to close all the leakage points. The leakages, through the leakages, you lose all the energy. And it doesn't really take a whole lot. A little gap here, a little gap there adds up to like an open window, a constantly open window and you, you try to heat against that open window.

So thermal camera costs a hundred bucks, at Amazon, and you plug it into your cell phone and you have enough to really detect the leakages in your building. Yeah, and Edgar, here's where we get the trade offs in sustainability. Many people care more about human health and the health of the people inside the building.

As we make airtight buildings, the materials we choose and the offcastings from those materials can have effects that are negative. You have a kid with asthma, for example. So there's a real fine dance between how much do we want to seal our buildings, how much fresh air do we want, and what kind of materials are we choosing. And, and the interaction between all of these is what makes sustainable design and architecture so difficult. And even for clients, eventually, you have to decide on the priorities that you're gonna have to emphasize in your project in order to go forward to make decisions. Someone else here asks, from, uh, a, a, uh, participant from Colorado asked, are there any thoughts on how to create sustainable homes and environments where snow covers roofs and still have panels for much of the year? I think solar panels is actually not an issue in, at this...

in, in areas where snow is backing up on the roof because the... there's a... Uh, first of all, they are pretty slick so snow can slide down they're warming up quickly, so they're developing sort of a water flow to helps to, to get rid of the snow pack.

If the snow really packs up and you have to get on the roof and you have to clear it up. But in most cases, it works actually pretty well. You know, I'm, I'm from Germany, and believe it or not, but more snow in Bavaria, but um, solar works, so solar panels on the roof. And they have a lot of snow, at the same time they have a lot blue skies. Colorado is a prime location for PV systems on the roof. Another question, um, that came up and I think, Marc, you might be able to have some interesting things to say about this, they were asking about how can we make tiny house options more acceptable to cities, towns, and counties.

This is an, an appropriate question today in Philadelphia, where our City Council is grappling with how to make use of, possibly make use of tiny, uh, houses to settle some of the housing problems for homeless people in the city. Any thoughts, Marc? I've done a lot of research on tiny houses, um, and I'm currently, uh, testing out, um, in a, in another project for, for, uh, glamping, you know, how do you make something relatively small, um, uh, that is... Now we're talking typically by the way, in the 400 square foot to 800 square foot range, um, and, and include everything that would be normally there, and do so in a cost effective fashion. And I think that it's a, an an executive, an executive summary fashion that it's clear now that there are ways to, to build using a modular approach, which Edgar is a bit of an expert on, and so I should not say too, too much, but with modular approach, in, in, in fact, we can put those components where you need not make compromises in luxury or in comfort or in technology, only in size, and keep the overall financial, uh, burden quite low, and, and of course, when you can keep the ongoing cost of maintenance, which often relates to power and water typically, uh, int- into a close to zero environment, now you're talking about the possibility, uh, Daryl, of, of, of having a solution for some of our population that is clearly challenged in, in, in, in having safe environments to, uh, to live in and be proud of and still allow some form of, of, of ownership, which we all know from a psychological and spiritual perspective is a great advantage to preserving the values that are, that are put there by, by societies.

Yeah, thank you. And here, here's one that's, uh, uh, sort of a technical question that intrigued me, um, because I haven't got any idea what the answer might be. The question is whether there is any architectural preference or whether the architects have preference for, uh, on, on self or preference for self adhered or liquid applied products for net zero architecture. Rob, you're laughing, you, you take this one.

No, I'm laughing because I, I have no idea how to answer that question. [laughs]. That's why I picked it up because it was an interesting question. As you, as you're looking, Daryl, let me quickly offer a bit of a, a commentary. One of the things that we consider, uh, in a longterm perspective is the, the...

when we apply things to a service is how much it cost to make the application. How long will the application lasts and when it starts degrading, how much of an environmental impact does, does this coating have on, on, on the environment? In other words, does it, does it have chemicals or toxins that are gonna cause a problem. And, um, and then of course the other is that once it's... once that has coming off, the material that was supposed to protect, for example, if you're talking about a paint or are we talking about, uh, uh, similar types, types of, of applications, wanna know what happens now to the maintenance costs, and what happens to the material that's now exposed? Does it start degrading before you get a chance to, to, to go in there and, and fix it up? And so techniques that are, again going back instead of high tech and using just smart techniques, uh, the Japanese, have a method of burning cedar, for example, and, and then scraping off the bra- the black part that you see, the, the, the, the charcoal part, if you will, and then it's been shown and proven that that kind of cedar, um, when properly, uh, without any coating at all, uh, will withstand, um, um, external weather, just as good as a CCA treated lumber, for example.

Um, and, and that is an example of a way to deal and move away from coatings, altogether. An- another question that, uh, uh, that came up, uh, had to do with the, uh, total carbon footprint associated with many of the ideas that you've discussed in your talks. I'm referring to all three of you here, actually, that, uh, obviously it's a very difficult question to assess. Maybe we don't even have the right tools to be able to make an assessment or proper assessment of the total carbon footprint of some of the, some of the, uh, uh, uh, the ideas that you came up with.

Obviously we're using windows that you talked about, Marc, which is, is totally better, uh, in terms of total carbon footprint than making new windows. Any thoughts on this? Uh, Edgar, how about you, do you have any thoughts there? Yeah, actually, I think you can calculate pretty precisely the carbon footprint of the building. And when I, when I say that, you really have to take the entire lifecycle of the building under consideration.

So it's the production of some material, the transport of some materials to site, which is a site of the assembly, the entire life, um, of the building and all the energy which goes into the building as well as in breaking down to material and separating that. So that's sort of the life cycle assessment and carbon footprint of the entire building. And different materials have different carbon footprints. Concrete, for example, is extremely energy, um, uh, hungry, and produces a ton of carbon, steel as well.

Wood on the other hand is actually carbon positive. So there is embedded carbon in the woods. So, so they, uh, you know, by the material choice, you really make a huge impact on the environment. And obviously, you know, global warming is not a myth, I think at the end of the day, pretty much everybody believes now that this is really reality. California is burning since month, so the energy we're pumping out into the environment, carbon footprint really matters. So we all need to really look at our individual carbon footprint, but also the societal carbon footprint.

Being mindful of, uh, the time, I know people have, uh, in the audience have set aside an hour for this program, and we're getting closer and closer to the end. I'd like to say that, uh, the speakers before we fully met today, uh, suggested that they would be willing to consider the answers to the questions that you have posed that we didn't get to in the discussions today, and we will try to assemble that and send that out to you by email for those of you who wish to receive that. So all of you who are, uh, who are listening in, we wanna thank you all for joining us today.

Uh, this has been a real pleasure, uh, to have the joint group of the ACS and the Science History Institute, um, working together. This is the first program we've done together. It's been a real pleasure from the point of view of the Science History Institute.

We hope to be doing more of them. Uh, we invite you to our next program, which is on November the 17th. The title is Here Comes the Sun: Advances in Solar Energy. Dr. BJ Kapoor is a, uh, an associate at the, uh... I'm sorry, he's also a member of the program committee at the, uh, Science History Institute and, uh, came to us after he had a...

not had, owned a solar energy company out in California, and has some very interesting ideas on, on where this field is going. Uh, and so, uh, that will be it for today for all of us, thank you very much again for joining us. Thank you for watching this presentation.

ACS Webinars is provided as a service by the American Chemical Society as your professional source for live weekly discussions and presentations that connect you with subject matter experts and global thought leaders concerning today's relevant professional issues in the chemical sciences, management, and business.

2021-04-16