The Global Economy After Covid-19 with Peter Marber, PhD

Hello, everyone, and welcome to the Economy Post COVID-19 with Dr. Peter Marber. As we get underway, I'd like to mention just a few housekeeping notes. Please utilize the chatbox to say hello from wherever you are in the world and use the Q&A box for any questions that you wish to pose during today's recorded conversation. We will try our very best to answer as many of your questions as possible later in the hour.

My name is Jill Felicio, and I am a member of the class of 2000 and 2013, as well as the director of advancement for the Division of Continuing Education. I'm delighted to welcome you today for this very important presentation. Harvard Extension School alumni leaders are working tirelessly on the boards of the Harvard Extension Alumni Association and its many global chapters, as well as on the board of the Harvard Alumni Association.

It is my pleasure and honor to work together with these extraordinary alumni to create professional, social, and learning opportunities for our 30,000 plus global community members. In fact, today's event was conceived by our exceptional alumni leadership of the Harvard Extension Alumni Associations, New York City chapter. Thank you all for this wonderful idea.

The pandemic of COVID-19 has sadly taken over 2.5 million lives around the world, heavily upended most education systems, and has had a profound impact on the world economy. As we begin to see light at the end of the tunnel with the start of vaccinations, I think many of us are cautiously optimistic for a return to a new normal. I'm delighted to have Dr. Peter Marber with us today

to shed some light on the economic ramifications of the pandemic as well as the path forward. Dr. Peter Marber is a renowned author, professor, and Wall Street professional, who has been a visionary leader, focused on globalization and financial markets for the past three decades-- an award-winning investment manager for some of the world's largest institutions, including Loomis Sayles and HSBC. Peter is currently the chief investment officer of emerging markets at Aperture Investors in New York. Peter has taught at Harvard Extension School since January of 2014, as many of you are well aware; has received the JoAnne Fussa Distinguished Teaching Award in 2017.

He has also taught at Columbia University, Johns Hopkins, and New York University. He has authored five bestselling books and over 100 columns and is routinely quoted in the National Media. He has served on the boards of institutions, including the New America Foundation, the World policy Institute, Columbia University, St. John's College, and the Emerging Markets Trade

Association. So without further ado, please join me in welcoming Dr. Peter Marber. Thank you So much, Jill. Whenever I hear me be introduced, it just reminds me how old I am, really, with all of that-- Thanks again for having me. I know we're all probably a little zoomed out. I tried to bring a little bit of the campus with this virtual background and talk to you a little bit about COVID because I know people have really taken this past year-- it just been so strange.

Some people have taken it, unfortunately, really hard. People have been isolated. A lot of pessimism out there, but I think there is actually some silver lining to all what's happened in the past year. And so I'm going to go through a handful of slides. I'm really not that good at following charts and questions, so maybe we can hold it to the end unless, Jill, there's some points where you think we can have some people jump in. Maybe I'll just stop and ask, and then we can have folks raise their hand.

So what I'm going to do here is I'm going to share the screen. And I hope everybody can see this. Beautiful. The COVID-- After COVID, that's right. We're going to talk about the global economy after COVID.

And really, there have been changes happening before that. But let's just really talk specifically about what's happened. We have an economic shock. I think it's very similar to a World War. We've got the largest contraction in modern times, maybe 5% globally last year.

And that was even with zero interest rates and huge amounts of deficit spending around the world. We still had this big contraction. And in the short term, though, I think we can expect a pretty robust snapback around the world. Vaccines are rolling out pretty quickly now. But I think there are some long-term implications of COVID, and we should take them into consideration.

Let's just first look at the facts, the economic impact of what happened. So what are you going to see here is a chart of a global GDP growth since 2000. I hope everybody can see that in 2009, we had the global financial crisis. And we definitely had a depression in economic output for a period of time.

It even might have looked longer than the "V" that we're experiencing here. But I hope everybody can see that this is a deeper jolt than what we had in the global financial crisis. And so it might actually take a little bit longer for things to come back. You can see, in terms of economic mobility versus COVID deaths, this is an interesting way to think about how COVID impacted countries. So here would be the loss to what was expected is GDP before COVID. And then we also have here the confirmed fatality rate.

And I hope everyone sees that it was really tough to escape the economic impact of COVID because of the globalized economy that has been being built for the last 20 or 30 years. So you can see, really, no matter where you were in the world, didn't matter how bad COVID had hit you, you saw some pretty steep economic hits. Asia held in a little bit better than the rest of the world. But you can see, really, there are parts of Asia also that got hit tremendously.

And then there are certain parts of the world, let's say, like Western Europe and the US, where we actually had relatively steep economic losses as well as human losses. So really, almost unprecedented certainly in my adult career of seeing anything like this that had taken its toll on so many countries. You can see, it's really hit employment rates. I have here mostly OECD. And I hope everybody can see that the US was one of the worst-hit along with Canada. You see these sort of relatively big spikes.

And even though we have seen a lot of the jobs come back, Canada and the US really have suffered a lot more than other parts of the world. They have an even better chart that just shows you the difference in unemployment between 2019 and 2020. And you can see that the US saw more than a 5%, more than a doubling of unemployment, about a four-point rise in Canada. Other parts of the world, particularly Europe, which actually have sort of better labor protections and different kind of work furlough schemes during COVID versus just outright firing people. You see, they've also drifted up, but they are not nearly anywhere close to the levels of the US and Canada.

And let's not forget, too, we got a lot of students that are listening in here. And some of you are also parents and have kids, and there's at least a billion five students who are out of school for really long periods during this pandemic. Again, these are almost unprecedented, more likely what you would have seen in a World War than really anything else in the last 100 years. And one of the responses that governments have made given that economies were hit so badly is just to use as much fiscal stimulus as possible. Really, it seems like countries have just forgotten all about it about debt limits and have just issued as much as they can.

You can see it doesn't matter really where in the world you are. Governments have had to step up and fill in a lot of the demand gap that the marketplace, the personal consumption, and business consumption would have normally taken up. So you could see in the United States, for example, we had almost a tripling of the deficit from 6.4% in 2019 to more than 70 and 1/2. It's going to come down in 2021 but not as much as people might think.

It's still going to be really high. And this debt level is going to stay-- there, it will sort of glide down. But we're going to have it for the better part of the rest of this decade. Other parts of the world, not as much. But the US economy, in some respects hit really hard by COVID given that so much of our economy is geared around personal consumption that just couldn't happen during lockdowns. And so the big economic bill to pay for all of this fiscal stimulus from government, particularly in the US, you can see is this very large debt to GDP level that we now have.

Now keep in mind, look how low it was in 2008 during the last global financial crisis. And, yes, indeed, it did creep up to 60%. But the truth is we really, in some respects, didn't recover very well or very slowly from the long that we have with the global financial crisis.

We've had to step up for the better part of 10 years. And now, we're going to have to step up for another 10 years after this crisis. And you can see that this is going to take us to 128% levels that we really have not seen since after World War II.

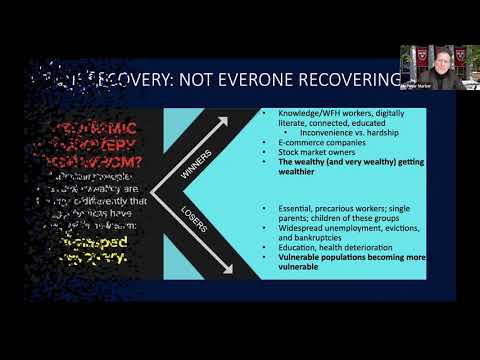

How many people have heard about the K-Recovery? I have to admit I had never heard about it until probably last spring, where people were predicting whether we were going to have a V-Recovery a U-Recovery. I've heard W-Recovery, which is like two little recessions tacked on to each other. But the K-Recovery is really a new phenomenon, which is that we actually have certain segments of the economy rebounding faster and others not rebounding at all.

So creating this sort of K pattern. So in this, what we see is that different people faring very differently in the economy, and that gave birth to this term K-Recovery. So the winners clearly, I think-- we know are knowledge workers; people who can work from home; those who are digitally literate, connected, educated. Yes, they've been inconvenienced by not being able to go to work, but it's not true hardship like it is for many essential workers who really have to get out of the houses and put themselves in harm's way.

Certainly, e-commerce, companies have benefited. Stock market owners have benefited a lot. And really, the wealthy and very, very wealthy have been getting wealthier. I think we all know that folks like Jeff Bezos and other tech tycoons have probably seen their wealth maybe double during the pandemic, particularly as more people switched offline purchasing to online purchasing. And the losers have tended to be essential precarious workers, single parents. We forget that 23% of American children actually live in single-parent households.

So children in these groups has taken their toll on a lot of folks. We've had widespread unemployment, as I've shown; evictions, bankruptcies; lots of people who have not been able to go to school; lots of deterioration in health outside of COVID. And the sad truth is in a lot of vulnerable populations have become even more vulnerable through the pandemic. We certainly know sectors like global tourism and travel.

Here you can see commercial flights? We aren't anywhere close to where we had been previous to the pandemic. Folks are expecting this to begin to pick up this summer and maybe return somewhere close to normal. Maybe it might be 2023, 2024 before we really get back to those 2019 levels.

So those sectors will continue to be hit badly. And then, of course, we know that shopping patterns have truly changed. You can see here-- interestingly, the US had the smallest contraction in what we call footfall. But all around the world, there was massive, massive contraction in the amount of footfall in shopping that we saw in 2021 versus 2020 before the pandemic kicked in.

And you can see this chart in terms of unemployment in the US, specifically, that, yes, a lot of jobs have come back. You can see it. But there's plenty that have not. So you can see here that there's over 7 and 1/2 million jobs were lost in leisure, hospitality space. Only about 4.2 million have come back. Still, a lot of people unemployed.

You can see it also even in education and health-- still, more than a million people have not gotten the jobs back. And you can go through this long list. So clearly, it's not like everybody has made it through the pandemic evenly. There's definitely been winners and losers. And in the global context, there are plenty of countries and swaths of populations that were slated to pull themselves out of poverty.

And you can kind of see that, actually, this will be delayed a little bit because of the slowdown in the global economy, which pushed some people back into poverty. And it might take a couple of years for the trends to reverse and get back to where they were pre-COVID. So you might ask yourself, what was the impact on the financial markets? And what I've said here is after an initial surprise, the markets have really recovered to almost record levels fueled by unprecedented amount of fiscal and monetary stimuluses, which is what we'll talk about here a little bit. So you can see this chart, which is the Dow Jones back in the first quarter of 2020. And you can see how it fell really quickly in about five weeks from middle of February towards the end of March. But really, things have bounced back pretty quickly since then.

And if anything, we now, like I said, are in record levels. You can see the different GDP changes over time. And certainly, we got a big boost when the vaccines were announced last fall. I hope everybody can see here, too, that this is not just in the US. You've seen a big snap back in the Nikkei, the Shanghai Exchange. A couple of places that have done worse-- Italy and places like United Kingdom.

And the FTSE 100 is the UK. But keep in mind that not only was Britain hit by COVID, but also Brexit. And so this has really been even a sort of a double whammy for that country, which is why the stock market really hasn't recovered so much just yet. And why have markets really recovered? Well, I think part of it is just the weight of money. So this is the amount of money and one in circulation. And I went back almost 50 years-- you can see this back to 1970-- and it normally, M1, stays in a pretty tight band anywhere from zero to maybe the most of the 15% growth.

But does everybody see this massive growth in M1 that occurred last year? We're talking about literally money being dumped by the Federal Reserve trying to prop up the economy any way it can. And a lot of this money filters itself back into asset prices. And this idea of pumping economies with money through zero interest rate policy or very low-interest rate policy, in some cases, negative interest rate policy, and also, things like quantitative easing-- I hope everybody can see the gold dot on this chart represents the five-year average M1 growth. And the bar chart, the blue, is what's happened just in the last year.

And take a look at this, folks. Would it surprise you to see that almost every country has been flooding their markets with money, with the exception of maybe China who already has a pretty robust economy and wasn't hurt very much by COVID? Every other economy has really doubled, tripled, quadrupled the amount of money in circulation than they have in the previous five-year average. And, in some cases, what we've seen then is the combination of stimulus checks going out to people, people not spending the way they have in the past, people putting money into stock markets in other kinds of savings and investments. I hope everybody sees that this has changed the trajectory, really, of savings in places like the US. US is here in green.

I hope everybody can see that we were hovering at a low of maybe 6% going into the last global financial crisis. But people have been saving more. And going into this crisis, we were probably closer to 10%.

But I hope everybody can see at one point, that number had spiked to almost 25%. It's certainly coming down as people start to spend more normally again. But there really has been a huge amount of savings going on during this pandemic. So there, again, a little bit of the silver lining.

And so, if anybody of you out there had been following the financial markets, you might be wondering like our asset bubbles actually building because of all this money. And I've seen a lot of asset bubbles during my time on Wall Street, but this one really is a little unique. And often, it's tied up with different types of technologies.

And a lot of times, it's just hype. But I hope everybody can see that, really, we have almost every asset class you can imagine has been attracting money. And I think part of it is when interest rates go to zero, people are just willing to speculate a little bit more with their money than they normally are. And so, if you look at things like Bitcoin or Cannabis or this Special Purpose, SPAC sector, or all types of online disruptors, all of them have gone to record levels, just crazy levels that we really haven't seen before.

But as you see, I've put this little question mark next to just regular stocks and bonds. Maybe they, too, are just-- average assets are being inflated because of this very, very low-interest rate environment that the government is using to prop up the economy. So there are people who might ask-- these bubbles, is there something that can cause it to burst? And I think the answer is what it typically is when it's a financially led bubble, which is rising interest rates. So what we've seen just even in the last two or three weeks is enormous volatility come back to the market because interest rates have started to creep back up. And it's interesting. It's not creeping up because the central banks around the world are hiking interest rates but, really, just this anticipation that the economy is going to start to overheat because so much money has been pumped into the economy and into all these financial markets that all types of discount rates and things have to be taken into account now if interest rates back up.

And just to put it in perspective, in the summer of 2020, the 10-year US interest rate for the bond, the 10-year treasury bond, dropped to a record low of around one-half a percent. That's amazing to think that for every $1,000 that you would invest in that, I think, you make $5 a year. Like, almost nothing. That's now backed up a little bit. It's now gone to 1.5%. And believe it or not, that 1% reversal in interest rates has caused a lot of asset prices to begin to deflate a little bit.

So maybe not necessarily such a bad thing. So what's the global economy going to look like after COVID? Well, I think a couple of things really in the macro perspective, I think you're going to start to still see how China has faster relative growth to Europe and the US, along with the rest of Asia. They were growing faster before the pandemic, but the pandemic has hurt the West more than it has Asia. And so, I would expect that region to continue to grow quickly and also gain what I would call a global market share in terms of GDP and output as well as growth. That's really going to be the engine for the foreseeable future.

I think we will have slower growth in the US and Europe. It might take us maybe three to five years to catch up to where we were headed before the pandemic. But with all of this, you can see some other things that were changing over time. This is looking at China and its trading partners.

And you can see that there was a point 10, 20 years ago when the US and Europe really were dominant, and the other Asian countries were in a lower position. But I hope everybody can see that during 2020, the Asian block actually surpassed the US and European Union as the largest trading partner to China. And I think that that's just going to continue, and that's part of that Asian dominance that I was just talking about will continue for the foreseeable future.

And I hope everybody can see that even though China's growth rate, which is in red, has been slowing and got hit during COVID, it has a pretty fast snapback. And it's going to keep gliding down. But even as it glides down, remember, as a percentage of the global economy, it's still growing relatively fast and will continue to move to be the world's largest economy depending on what measures you use within this decade or next decade. And part of this might be fueled by what folks have called commodity supercycles.

This is what we've seen in previous big bursts. We saw it around 20 years ago when huge demand for commodities and manufactured products create some global trade. Interest rates in China and other emerging markets are higher, which starts to attract capital to them. What happens then all this capital flow builds into these countries reserves, their credit ratings improved.

It strengthens their exchange rate, which improves financial conditions for companies within the country. The countries grow faster, and they get this virtuous cycle of prosperity spinning. Anybody who's taken my emerging market course that Harvard knows I'm big on these virtuous cycles. It could be that we are starting to see one of them begin again.

And this could actually be good news for the world. And during this period when we have that kind of supercycle, often what happens is the dollar weakens. As I mentioned, we saw about 20 years ago-- the dollar weakened from around 2000 going into the global financial crisis. It then strengthened for a few years, but a lot of people believe that this cycle is now about to reverse.

Maybe it'll go and run for another few years. You can see that since last March, the Federal Reserve Bank in St. Louis actually noted that the dollar peaked in value in March of 20 and has now dropped about 10% since then going into February. You can also see it in crude oil prices.

This was at the bottom of the COVID meltdown, but it has subsequently rebounded back to pretty close to pre-pandemic levels. So we're also going to see a lot of exporters benefit from that. And so this oil supercycle that we haven't seen for a while could be going. You can see the last upcycle that really started even before 2000, lasting into the global financial crisis, then we went down. And maybe COVID is the beginning of it turning back up.

You certainly see it in ANC's China Commodity Index. They say that has actually taken a big turn positive. So maybe we are amid that big turn. But maybe we could talk then in the bigger picture what life was like before COVID and what it might be like after. So certainly, before we all know about globalization and the supply chains that have been building for the last generation, we had big trends in urbanization all around the world, including places like China.

We know that a lot of this was driven by shareholder capitalism. We know that this was traditional work at the office. We all shopped at stores largely. And it really was a kind of a Western dominant global order that had been set up really at the end of World War II and really has lasted for the better part of-- I don't know-- 75 years. But after COVID, I think we may see this in history as some kind of a dividing period.

I think we're going to start to see much more regionalized economic activity. And we all know That-- if you remember, about a year ago, we were worried about getting masks, and we couldn't get all that gear because it was being made in different countries all out in Asia. A lot of it was linked to China. And we've realized that we've got to diversify supply chain.

So you might see regional supply chains start to sprout up all around the world. And instead of us only living in urbanized centers, we might see more diffused living in less denser places. We all heard about people who have left cities to live out in the country during COVID. A lot of those people might not be going back. And with technology now, people have been able to keep in touch relatively well.

So we might have just more diffused living patterns than we had before. And I think we've all also heard about stakeholder capitalism and ESG broadening out beyond just shareholders. It's clear that shareholders have done well during COVID with these financial markets just booming. But I think everybody realizes that there's more stakeholders out there. I've been shocked that every day my email inbox is filled with stories about more ESG investment products on Wall Street.

Everybody's launching new funds, hiring more people. This is more of a serious trend. I don't think it's just a fad that's going to be going away any time soon. And I think you are going to start to see more flexible work conditions that allow people to work from home if they want to. Maybe not full-time.

But certainly, it will become much, much more common for people to not be in a physical office every day the way that we think about it before COVID. And certainly, more online commerce. I mean, I'm sure lots of us who are watching this now have changed our patterns for shopping and have opened up all types of delivery accounts during COVID.

I think this is also just going to continue, not only with food and goods but all types of services, I think, are going to continue to flourish online. And again, don't forget what I said about Asia and China rising. I think this could be the beginnings of a shift in global power. It might even be similar to the post-war period, where the US and Western Europe really set the rules and set up the global system. But that system may be altered a little bit now as we've got some new important economic powers in Asia entering the center of the global economy. And so I hope that after all of this, you could look at the glass and say it's half-empty.

COVID has been a big hit. But I don't want anybody to really be pessimistic about this. I actually am pretty optimistic about where we're going. There's a lot of interesting things about low-interest rates.

We say some of that money went into things like Bitcoin. But for the last, say, 10, 12 years since the global financial crisis, interest rates have been pretty low, and that has gone into a lot of technology, research, and development. And there are new things that are about to, I think, really jump out at us and transform life. So this is an interesting chart. Again, from anybody who has taken my Emerging Market classes from my book From Third World to World Class. I wrote it back in '97.

A lot of the things I wrote about have largely come true. And one of the big themes there is that there have been these technological waves where something new is introduced in the world, and the world bids it up for about 25 years, and there's a boom. And then, there's a 25-year lull. And it's during those lulls when you actually get more research and development that leads to the next technological breakthrough. And this pattern had been repeated, really, for a couple of years. And I thought when I wrote the book in '97 that the latest peak of technological upswing would have been in 2020.

But actually, in retrospect, I think it's probably more like 2007, right around the time that the global financial crisis was going to kick in. And I think that these cycles, instead of being 25 years up and 25 down, are now more like 12 or 13 up, a similar amount down. And if I think about it going forward, it makes sense because information technologies, computing robotics are speeding up technological change itself. And so I think that if you look out there to things like robotics and artificial intelligence, the internet of things, and virtual reality; space has so much opportunity now; green energy, agrotech-- I was just reading about lab-grown meat that was just developed in Israel, which is going to revolutionize factory farming; and biotech revolution and CRISPR-- there's just so much going on to be really, really excited about. And if you really think about it-- I don't know how many of you have watched a lot of Netflix and other video while-- I was watching the whole Marvel Comic Universe series again.

And I was watching Iron Man, and I saw this holographic image of what a computer is going to be like in the future, where you actually can manipulate it in the air. And what's interesting about this kind of virtual computer system is that we're getting closer to this than you really can imagine. It's going to be a lot better than Zoom, folks, I could assure you.

I've been actually looking at a system out of Chicago-- it's called Spatial. And you put on your goggles, let's say, for like a Harvard Extension class. And you'll put your goggles on. And instead of just looking at a Zoom screen of boxes of people, you'll actually see avatars. And you can actually then put yourself into a room that has all these kind of holographic blackboards and whiteboards, things all over that you can just grab with your fingers, in some cases. And this is actually more science fact than fiction.

And this stuff is coming, folks. There's a lot of other things that are on their way. Virtual reality, AI, robotics, autonomous driving, these are going to be breakthroughs for the planet. I think we're going to see expanded green energy. Things like solar and hydrogen are certainly going to be coming online. You hear about electric car companies every day going public.

I think, actually, exploration in space is going to help a lot of these sectors and other ones. We'll be putting up more satellites in space because things like virtual reality and autonomous driving and just video everywhere is going to require more bandwidth, so we need more satellites up in the world, up in the atmosphere. And what we're going to have to do is probably launch, I don't know, double or triple what we have. And if we do, you're going to see data costs drop dramatically.

And that's going to accelerate a lot of other economic sectors. And we'll also, hopefully, will be seeing within maybe 10 or 20 years solar panels in orbit for earth energy. They could actually face the sun 24/7 and actually much more efficiently capture solar energy. And with systems to bring it back to the earth versus putting up solar panels on your house and having to worry about clouds and nighttime when you don't get enough access to sun, really, very inefficient space can be a very efficient way to transform our energy system. There's also lots of mining opportunities for rare metals on the moon and other asteroids, which means that we don't have to do it on Earth and wreck the planet. And some estimate the space economy is going to jump to about a trillion by 2040, maybe $3 trillion by 2050.

And I also don't want you to forget about the agro, biotech revolution. I mentioned things like lab-grown meat, but there's also things like CRISPR and a lot of other technology-driven health solutions that I think are going to help conquer lots of diseases. In fact, you could even look at COVID and how quickly it was solved because of a lot of these new biotechnologies. If that's not enough reason to be optimistic, let's not forget that 2021 is the year of the ox. And guess what happens in those years, folks? Well, according to State Street, here it says that the stock market generally averages up 13.5%. So at least maybe be optimistic for the rest of the year.

Let's just summarize by reminding everybody that this is an economic shock-- COVID-- but the recovery has started. It's begun. We've had unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus. Yes, there may be some asset bubbles brewing, but I think that they're generally self-corrective.

And I don't think there's going to be anything terrible on the horizon. I think that COVID may accelerate Asia's faster relative rise to Europe and the US. I don't see us declining very much. But certainly, I could see Asia really vaulting to the front and center of the global economy.

And I want you all to be optimistic because I think that there are new technologies that are coming. And this may help in the post-COVID economic malaise that maybe some of us have been feeling. Thanks so much.

Why don't we open up for questions? Wow, Peter. Let me just say, on behalf of everybody, that was fascinating, and I can feel your optimism. It's amazing. I'm monitoring chat, and I'm seeing quite a number of questions and curiosity around that rise of China in the East. And I wonder if you could say a bit more about that, like how long you think that will last, relatively speaking, and any other factors that may implicate changes for that based on the new administration and policies that are coming.

Yeah. I think that, first of all, I'm not sure that like a lot of the economic sanctions that the previous administration put in place, if they're necessarily going to get rolled back any time quickly. But as I showed in those charts, a lot of China's economic trajectory is tied in with other parts of Asia, and they're all doing relatively well. And so I would expect China just to keep grinding away. A lot of people are looking to maybe around 2040 when China is purportedly going to hit what they call the demographic cliff.

So there are a lot of people in China, but it's also one of the older economies in terms of the average age. I think the US and China actually have about a similar age. But China is supposed to get older. A part of that is that they had the one-child policy for so long that their demographics have been truly skewed. They've recently had to relax that, Jill. They actually relaxed the one-child policy to try to encourage more population growth.

But I think this is going to be the story certainly for the next couple of decades. I don't think that China is going away any time soon. Great.

"Can you say just a bit more about that relationship China has with the Southeast Asian partners that are becoming quite close? Has that historically have been the case, or do you see that happening more frequently now, and will that trend continue?" Well, we certainly saw in the fall, there was a very large trade pact with more than a dozen countries in that part of the world led by China. China also has their Belt and Road Initiative, which really is supposed to go all the way from Asia through Eurasia into Europe and tying up a lot of other countries. So this, I think, like I said, this is not a fad. This is a trend that's going to be with us for the next generation. And as a lot of my students have seen charts that I'll bring to class, we forget that China is a 5,000 plus-year-old civilization. And for-- I don't know-- probably 48 of the last 50 centuries, it has been the largest economy in the world.

So really, what you think about it, it's only been the last 200 years that the West kind of vaulted past China. But now, we'll see China regain its footing, and I think it's going to be that way for a period of time. I think we should realize that China's trajectory and the US's are really-- they're almost equals in terms of size of their economies. Maybe to put it into perspective, too, you could put the whole EU together, and it would equal about what China is. But as we see, European demographics continue to really just shrink in age. Europe has-- we have about, I think, three countries in Europe that are already starting to depopulate, meaning their death rates exceed the birth rates.

And immigration is not filling the gaps. So countries are actually shrinking in size. We've first saw that in Japan in the last decade.

We're starting to see that in other parts of Europe. So I think really looking out, projecting out to the middle of the 21st century, it's really kind of a showdown in the US and China. Fascinating.

"You mentioned Bitcoin in your presentation, but I wondered if you could elaborate a bit more on cryptocurrency. Do you have any predictions on the value and where that goes? Yeah. I mean, I appreciate what it's all about.

I appreciate blockchain technology that it's all being built on. Crypto is an interesting idea. It's really the domain of young people who are all online already. They already have digital lives. And so it naturally makes a lot of sense to them why Bitcoin would be the thing that people would want to believe in.

I don't know. To me, any asset that has a speculative quality really can't be a storehouse of value. So it could be a traded asset.

But it would not surprise me to see lots of digital currencies be rolled out in the future cryptocurrency by central banks themselves as a way to probably, I would say, if not, control crypto. But certainly, we don't want people to get weaned on this and lose money. We saw what happened with things like GameStop last month, where assets can go up literally 40 or 50 fold for no reason other than a wish of speculation, only to see things collapse quickly after.

And so, of course, regulators are always worried about retail investors, unsophisticated investors getting kind of fleeced. Crypto could be one of those things. But I think that the underlying technology absolutely, positively is going to be with us for a while.

Great. And getting back to interest rates and inflation, "What's your prediction for the interest rate, and do you think that inflation will become a factor, particularly for the US and Europe, for months or years to come? - Yeah. Well, one of the things that this webinar is doing is taking me away from listening to Jay Powell and his testimony today. But I think that the market already believes rates were artificially low last summer, and they've already brought them back up. I would tie it all together with a little bit of my technology discussion and just to say that I think with the exception maybe some commodities that material goods inflation could be a thing of the past. I think the ability to scale demand-- we have a lot of what I would call deflationary pressure that can keep the cost of goods very, very low.

And I think that that will really put a lid on inflation. So while I think interest rates were low, I don't know how much higher they're going. They're certainly not going to go high the way they were when I was getting out of grad school. I always tell people the first time I got a house in the late 1980s-- the mortgage was 10 and 5/8%, Jill. And to think like that, anybody could afford a mortgage with 10 and 5/8% the interest rate. But that's where interest rates were.

And, in fact, even in 2000, mortgage rates were around 8%. So now, people are regularly getting them at mid around 3% or the threes. I mean, I don't see it going anywhere back to the 8% or 10%. In fact, I would be surprised if we even saw it back up to even 4% or 5%. So I'm pretty comfortable that rates were pretty low.

They're backing up. Maybe we've seen most of the big backup. Great. Oh my goodness. Yeah. I'm glad to hear that we're not going to be back up that high.

That's frightening. Now "Our new administration is just a little over a month in. Can you speculate if there is any risk associated of tax policy changes that may impact the stock market?" I think that there may be some adjustments in things like in capital gains tax rates, which are relatively low. I think we all were made aware-- I think it was back in the 2016 election when Warren Buffett was actually publicly saying that he wanted to see higher interest rates for wealthy folks because most of the super-wealthy in this country drive a lot of their gains from stocks and bonds, investments, not from labor and income. And so it's strange that in this country, we tax labor at a higher rate than we do investment income.

So I think at one point, Warren Buffett said that he was paying a lower effective tax rate than his secretary was. And so bringing a spotlight on that, yeah. I've written an article recently that said I think that to some extent, capital gains taxes should be relaxed or eliminated, particularly post-COVID, because what we're doing now is going to be taking on this huge amount of debt for the future generation. And we should probably have the wealthiest people pay more taxes to kind of absorb their fair share of these pandemic costs, particularly because if you remember from the K chart, the K-Recovery, who were the big winners out there? They tended to be wealthy people who had money invested in the stock market. So not only have they gotten this windfall from low-interest rates, which puffed up the value of their assets, but we didn't tell them, well, guess what? We also are going to tax that at a lower rate.

So I personally think that it would be much fairer to have that tax either eliminated completely or adjusted to sort of reflect what's going on during the pandemic. Yeah. We have great concerns in chat related to inequality and the furthering the inequality with the changes.

Now "Are there any other ways to affect that rapid rise in inequality or close that gap? Are there any economic measures that are on mind other than what you've already mentioned?" Well, I mean, there certainly are taxes that is the quickest thing that we can do, right? The other thing, obviously, is that when we do have these stimulus plans, we could actually target it to the people who really need it. Like, the last thing we need to be doing is sending $1,400 checks out to people who don't need it. And they're just going to sit at home and put it the stock market, right? So we could probably be a little bit more effective in those stimulus plans. And I think that there's enough progressive elements in the current administration.

Remember, it really took a coalition to get the democratic victory. And so there are lots of ideas that we all know from people like Bernie Sanders and other, let's say, left of center Democrats, where I think some of these policies are going to come in. I think maybe we'll see some revamped student loan, student debt scheme that comes into play.

And it might also be that if we could get some infrastructure bill put together, infrastructure something that both Democrats and Republicans both talk-- they talk a good game like we needed. And certainly, I think we all would agree we've got crumbling buildings and bridges and tunnels and roads. And that could put a lot of people to work, particularly low-skilled people who have lost a lot of work during COVID. We could put a lot of those people to work in infrastructure, which really benefit the whole country.

We haven't had a big investment in what we call common goods in a long time in this country. And I think if anything, that the pandemic shorted is how we really do need good infrastructure to handle the future. We don't want to have what we've just witnessed in Texas. I mean, if you think about how many crises we've seen just in the last year, whether it's wildfires out in the West, whether it's power failures or floodings, a lot of this is infrastructure-related.

And it would maybe be a good idea to refocus our attention to getting the nation fit again. Absolutely. Infrastructure related but also hints of climate change, which is another theme in our chat. "Do you see climate change as having a heavy economic impact? Are you already seeing it, or are you seeing it being exacerbated in current circumstances? Yeah.

I'm certainly not a climate specialist. I'm not a meteorologist or even a TV weatherman. So it's hard for me to really give you a big picture on climate. All I would say is that the fossil fuel economy, which is really driven Western civilization from the last 50 years, 200 years, right? This has to change. I think people realize it. And you're already seeing some pretty decent pivots towards that new future.

I think that when you have people like Elon Musk and lots of followers worldwide believing that we really should be weaning ourselves off of fossil fuels, we're going to get some change. Now, whether it's too little too late, who knows, but I certainly think that you're seeing in the marketplace people willing to start to go to these new innovative technologies. So I'm encouraged not only to see EV vehicles but hydrogen. And as I mentioned in the presentation, I think that space offers a huge, huge untapped amount of cheap unlimited energy that could have a transformative effect on human civilization.

We forget that, really, what separates a lot of developing countries from advanced is simply energy. Like, a lot of these countries just lack energy and industrialization, and if there was cheap energy, I think you could see development accelerate dramatically. So I'm pretty excited about that. That's great.

Yeah. That incredibly exciting. Now there are a number of questions related to your take on the strength of the dollar.

Where does that trend go? Any thoughts? Yeah. Like I said, I've shown the cycle theory. And one of the reasons I showed it, Jill, was because I probably got about eight or nine different banks from Wall Street and sent me charts that looked like exactly like that. And I just said, oh, this seems to be a kind of a theme. What's interesting about these commodity supercycles, though, is that normally, it's the US has to import all of this.

And historically, we certainly, over my adult life, we've had to import oil. But I hope everybody realizes that back in September of last year, actually, we were exporting oil from the US. We were producing 13 million barrels a day. This is a several million from what we were doing 15 or 20 years ago.

So it's possible with all the shale revolution and the fracking that's been going on that we actually have this potential to export energy. So if there is a little bit of a boom, the US might actually be an exporter and a beneficiary from all that. And that actually would kind of mitigate a lot of the dollar weakness that we've seen, at least historically. Because if we go back to the 70s, probably half the trade deficit in the US has been tied to energy imports. So if we no longer have to do that, actually, maybe the dollar cycle-- it might weaken, but it might not weaken as much as it has in the past and maybe not for as long as it has in the past. So I'm not really-- I'm not a super believer in the dollar theory.

But if it does really start to kick in, it has tended to last for a while. So I would just say keep your eye on it because we seem to be right on the verge of either a change or [INAUDIBLE], as we say. Great. We have attendee's joining us from all over the world, and we have a huge population in Britain.

Do you have any thoughts on the outlook for the future of the UK economy, especially considering COVID-19 and Brexit? Well, I hope things go well there because my daughter actually moved there just about a year ago, just before the lockdown started there. I think that the UK is going to have an odd transition period as it unwinds from the EU and finds its footing with other trade partners as well as having to dig themselves out of all the COVID-related problems because you saw from my charts that they've been hit badly like we have here. We're all sitting with deficit spending, lost a lot of lives, had huge medical costs, a lot of [INAUDIBLE]. So I think that there is going to have to be a transition period there.

But I think I'm optimistic there as well because it's one of the great knowledge economies in the world. And that's what it's going to take to be competitive in the 21st century. So fingers crossed for the UK. Yeah, here's hoping. Now, any thoughts on a related note to how Africa fares over the next handful of years and how COVID has affected our eight rebounds? Yeah, I think that most people were pleasantly surprised that Africa actually was able, at least from the health perspective, was able to insulate itself relatively well from COVID. The cases there, the numbers are much lower per capita than what we've seen in advanced parts of the world.

Part of that could be that there have been other health crises in the last couple of decades that are fresh in their minds, and so that they adhere to all the lockdown policies and quarantines. I would say that in that tech future that I laid out, one of the big issues for where Africa will fit into that is that there still is a fairly large digital divide in Africa. And that was made clear during COVID. A lot of people who were cut off from a lot of interaction. And I would say that that has to be a priority post-pandemic for the African continent.

And already, the Chinese realized this. They've already been out and about lending money trying to help build infrastructure. But that digital divide is going to be important.

Because as I mentioned, so many of the great technologies that we have today and the ones that are going to be rolled out in the next decade or two are going to be very dependent on the bandwidth and information we're going to need to wire everybody up. So that's a pretty big continent with dozens of countries. And it has one of the lowest internet penetration per capita, really, in the world. So that's something that I think will be the big difference in Africa, is that whether they can wire themselves up fast enough to take advantage of all these new technologies.

Because you have to believe that the model of development where countries started manufacturing, let's say, something simple like t-shirts or gloves, and then maybe moved on to something like toasters and then to televisions or something. That's the way that most economies for the last 200 years have been improving their productivity and building their economies. But it's going to be hard to penetrate into global trade when we now have to fight against manufacturing in Asia, and in other parts of the world, robotics kicking in that will actually put a lot of people out of work.

It's not going to be that easy to wedge human labor into that way that we had done in the 19th and 20th century. So the way that you advance in the 21st century is to wire up, get people digitally literate, and let them thrive in that digital environment. And hopefully, that can spawn economic growth within the country without having to get into the global trade game the way the export model led countries from Asia did, and Europe did in the 20th century. Yeah, absolutely. Well, we're getting to the top of the hour here, so we're almost out of time.

But I know that you have been teaching at Harvard for a number of years. And we have many of your students on today who are giving you compliments and shoutouts across chat in the Q&A. So I wondered if you wanted to take a minute to talk about your experience here. Well, I think that HCS is really one of the great institutions. At Harvard, I think that it just provides a great opportunity to almost anyone around the world to access world-class curriculum and professors. You get to meet incredibly interesting people.

And I just hope that we can open campus again because I think we all think Zoom is perfectly fine, and we can all kind of get by. But a lot of what we want to do with education is not just get by. We really want to meet our fellow students, build our networks, and socialize because humans are social creatures. And so, hopefully, we can wrap things back up maybe in the fall. Certainly, I feel like I told everybody I should be vaccined before the summer. I'd be happy to come back and teach on campus if we open up.

So I just-- I know that actually, HCS has survived and even thrived during COVID. So hopefully, we'll come out of this stronger than ever before. And so big shout out to all my students. Awesome. We're all doing well. I could not agree more.

I mean, we were Zoom experts before this pandemic. And I think Harvard Extension School has led the way in online education for decades and really has taken a lead at Harvard and helping the rest of the University get up to speed in what we have perfected over decades. So nothing but good things to come, and we can't wait to gather in person as well. So, Peter, we would love to have you in person in any of our major cities, and we look forward to seeing everyone just as soon as we are safely able to do so. So please continue to let us know what topics are of most interest to you and join us again at another virtual event.

And Peter, thank you so much. This was fascinating, and very grateful that you have given us the authority to share this recording. It will be available within one to two weeks, so look out for that. We will email that recording directly out to everyone who registered today, and it will be shared on Harvard Extension School's Youtube channel publicly.

So please watch it back. I know I will. Wonderful presentation, and all the best to you.

And, Peter, any last words before we wrap it up? No, just get vaccines as soon as you can, folks. All right? That sounds good. All right. Take care. Thanks, everyone. Be healthy and well.

Bye. Bye-bye.

2021-03-17 11:14