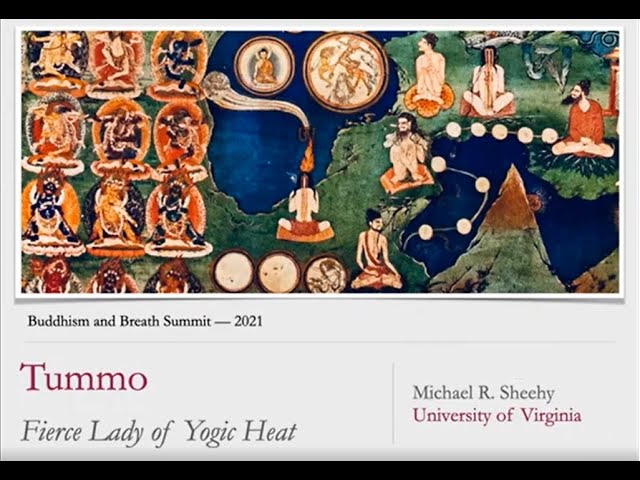

Tummo Fierce Lady of Yogic Heat Michael Sheehy

Hello, I'm Michael Sheehy from the University of Virginia. Today I'll be talking to you about tummo contemplative practice in Vajrayana Buddhism, as part of the Buddhism and Breath Summit. An outline of what I'll be discussing today begins with what I call "Yogic Buddhism and Breath". We'll then discuss some of the underlying theoretical and philosophical underpinnings of the practice of tummo, and the practice of yogic heat itself. Then switch to discussion of tummo in the modern imagination, and really the Buddhist imagination over the last 100 or so years. We'll talk about scientific research on tummo that's been conducted, some of the

physiological effects, and I'll conclude with some discussion on the technologies of breath. Tummo is a paradigmatic contemplative breath work practice of Buddhist tantra. The term tummo literally means "gtum" - or fierce, "mo" - lady or woman. Mo here is a feminine marker in the Tibetan language and is the translation of the Sanskrit term "candali", a class of goddesses. It's often translated as "inner heat" or "psychic heat" or "mystic heat" or "fury fire" etc. You'll find many different translations,

though this is not the literal meaning. There's a descriptive yogic language of heat for visualizing fireballs, wearing the clothes of inner heat, eating the foods of yogic heat, stoking the inner embers, bliss warmth, etc. Tummo can be a stand-alone practice or an enhancement practice, a so-called bogdon or enhancement practice, to complement ancillary yogic practices. Practice is applied in a modular fashion, and over the history of this practice, tummo, there's a variety of perspectives that have emerged about when to practice and which ancillary practices are conjoined with tummo. It's important to keep in mind that tummo is embedded within a broader Vajrayana contemplative curriculum. That is to say, there's a contemplative program in which tummo is situated. This begins with the ordinary preliminary practices, reflections on the preciousness and rarity of being a human being, having a human life, impermanence of that human life and your own mortality, but also the impermanence of phenomenon, the transience of all things conditioned, reflections on the pain and the sufferings of the world, that is to say, there are stresses and a sense of dissatisfaction that pervades living beings, and there are causes and effects in contemplating karma or the causality of the physical world, but also of one's own actions. What one says and does and thinks effects other beings as well as oneself.

One shifts then to the extraordinary preliminary practices, that is to say, going for refuge in the Buddha, the dharma, and the sangha - the teacher, the source of the dharma, the teachings, and the sangha or the community of support and the networks of support for practitioners. Generating an altruistic aspiration to awaken, that is to say, to be free from the pains of the world, not only of oneself but really understanding in a deeply empathic way how that transfers to all beings who experience pain and suffering in the world and wish for them to be free from that, so working towards that. There is a practice called mandala offering of the cosmos, in which one imagines the entire physical cosmos symbolically represented on a plate with precious gems and substances piled high, and then one offers that as if offering the entire cosmos as a profound act of generosity and extension beyond oneself to the cosmos at large and of the cosmos at large. There's a practice on purification called Vajrasattva deity, where the deity Vajrasattva, this pure, crystal, translucent, white deity pervades one's body and mind stream to purify all of the stains and impurities.

Practice of guru yoga in which one connects with one's own personal teacher who one has studied with and received transmissions, but also the broader historical family tree we might call it, the assembly tree of the lineage masters, and those who have historically received transmission and passed these teachings on into the present. There's generation stage practices of deity yoga, and completion stage practices which involve somatic yogas. Generation stage is a process of simulating oneself as the sublime body of a deity. These are a main set of Vajrayana practices. Deity yoga, otherwise known as deity yoga is a performative visualization based on a script called a sadhana, and the sadhana is ritually performed with gestures and bodily postures, mantras that one recites, and visualizations. One begins by reducing all phenomena in the universe to emptiness.

From that emptiness the practitioner generates their ordinary body as the sublime body of a deity in the environment of a mandala - the sights and sounds and smells, the entire experiences of the deity. This process is designed to transfigure the ordinary habitual bodily image and sense of self in the world to the sublime sense of being a deity in the mandalic surround. The sadhana practice concludes with the dissolution of the deity and the mandala into open silence and reemergence of the practitioner or the self into the ordinary world.

Following the generation stage practices are the completion stage yogas that are sets of tantric practices designed to somatically and cognitively transform the ordinary body into a sublime body. That is to say, once the generation stage practices of visualizing oneself and orienting oneself in the environment of the deity and the sublimity of the deity, one then shifts to these more somatic body-oriented practices that are designed to move one from a non-buddha body to a buddha body. These practices apply somatic yogic exercises, breathwork, ritual, and visualization to manipulate interior vital bodily energies. These practices are interested in also harnessing extreme experiences, including hypnagogic states such as falling asleep, dreaming, also dying, orgasm etc, that is to say, threshold experiences at the edges of the self, the edges of ordinary self-experience.

These yogas simulate and mimic the radical threshold experiences to transmute these energies into insights. It's important to keep in mind that there are myriad systems of yoga practice, and in particular these completion stage yogas, that tummo breath work is integral to completion stage yogas and is foundational to transform the body in several tantric systems. Tummo however is not a single method. The techniques are applied with degrees of variation in distinct tantric systems, and you'll find in meditation manuals and in different living traditions different presentations and instructions on tummo. For instance,

tummo is integral to the tantric systems, most famously perhaps is the Six Yogas of Naropa, but there's also Six Yogas of Niguma, and you see a painting of Niguma here, the Lamdre, Six Yogas or Six Vajrayogas of the Kalacakra Completion Stage, Guhyasamaja Completion Stage Yogas, etc. You'll also find tummo in the post-tantric systems of Dzogchen and Mahamudra. There's a discourse within Vajrayana about whether the body or the mind are primary and predominant, and in fact, depending on the tradition and the sort of series of teachings that you're receiving, one will place the body or the mind, or the cognitive or somatic processes as predominant.

Here, this 13th century Tibetan Yogin Yangonpa says "If you don't understand the actual abiding nature of the body, you don't understand the vital point of the meaning of meditation". So clearly here, Yangonpa, and this is in a book that he wrote, a text on the subtle body, is placing the body at the center of the discourse. So in order to understand tummo we have to have some understanding of the anatomy of the subtle body within tantric physiology. The philosophy of tummo is that life depends on warmth. So heat is volitionally mobilized to transform the person. It's very important that there's an understanding that at the primal basis of life there is warmth or heat, and there are models of the gestation of the human body that begin with warmth at its core. Tummo is a practice that harnesses this warmth in order to transform life.

Tummo practice is based on the tantric physiology and an understanding of how to manipulate the underlying flows and mechanisms of the subtle body. Within tantric models of the body you'll find a typical three-fold orientation; a coarse or physical body, a subtle, and an extremely subtle body, that is to say shintu lu and a shintu trawai lu, subtle and extremely subtle. The subtle is a visceral body, it's a felt body, it's a body with affect, and can be manipulated and mobilized via interoceptive methods. It's also referred to in the literature as a vajra body or an adamantine body, and typically when we're discussing this vajra body or the subtle body we'd say it's constituent of rtsa rlung thig le, the channels, the winds, and these nuclei. A subset of the channels are the chakras. Channels are three tube-like pathways that run vertically from the brainstem

to the perineum, that is the space between the anus and the genitals, the base of the spine, and align parallel to the spinal cord. There are subsidiary channels throughout the body as well but these are three primary channels, and along the central channel or tube are chakras, which are vitality centers or wheels that rotate clockwise, and in some traditions counterclockwise, along the central axis of the body at the crown, the throat, the heart, the navel, and the genitals. Again, there are different placements in different tantric systems and different numbers of chakras, four, and six, and so forth. Winds or what we might call wind-breath are currents of breath and vital energy that circulate and flow up and down the channels, so these are the movements, the currents. The nuclei are refined seminal essences that resemble the shape of liquid drops,

sometimes these are translated as drops. Here we have two photos of 20th century Tibetan exemplars, the 16th Karmapa Rangjung Rigpe Dorje, and Dilgo Khyentse, both seated in these yogic postures, holding these positions associated with tummo practice. There are a series of different postures and yogic exercises performed with all of the completion stage yogas and tummo specifically. These are called in different traditions tsa lung, or trul khor, the magical devices, and are practices or exercises for training the physical body, lu jong. It's important to keep in mind also that tummo is a contemplative practice, and it's really a formal practice. The practice of tummo mobilizes vital winds and energies within the subtle body to enter into the central channel, and this is the primary theory of tummo practice, to mobilize the vital winds and energies into the central channel, enabling these currents to be harnessed for transformation, for transformative ends.

So principles of this practice that are important to keep in mind are that this is a formal practice, there's a time, a setting, a location, a posture, an intent that is set, this isn't practiced in an ad hoc fashion, sort of on the fly or off the cuff. Tummo follows a scripted sequential technique that engages the body, the breath, and the mind, and that there's a formula to the practice. Although there may be variations, it is formulaic. It involves monitoring one's experiences and making adjustments to emergent experiences, to signs and measures that may be described in the literature or by one's teacher, but also pitfalls and obstacles that might arise. Tummo is practiced in sessions that are measured by temporal durations and framed within time, within frequency and the regularity of practice, as all practices are. There's an imperative to practice under the supervision of a qualified teacher who can be responsive to emergent experiences, to falling into pitfalls for instance, to signs that might emerge that might not make sense to a novice practitioner, and this is critical.

Though we have the literature and instructions and descriptions on how to practice these practices, all of that accumulatively, all the practice instructions in the world don't add up to the value of a living teacher who can be responsive to one's experiences. The outcome of this practice is the coalescence of bliss and emptiness, a kind of non-dual experience. As we talk about heat and the arousal of yogic heat, this is important to keep in mind. So with that as background and a kind of frame of the anatomy of the yogic body and some of the associated practices that make up tummo as a kind of modular contemplative practice, let's now look at a specific instruction from a meditation manual. This is written by Thangtong Gyalpo who's a late 14th/15th century yogin in Tibet who wrote this instruction on the Six Yogas of Naropa. Thangtong Gyalpo is famous for building iron bridges across Tibet and Bhutan and for introducing Tibetan opera, and in his instruction text here on tummo he writes, "after slowly clearing out the stale air, slowly inhale equally [into both nostrils] while drawing the winds in and down.

Slowly draw up the lower wind, joining the upper and the lower winds at the navel". So the winds from the brain and the winds from the perineum or the base of the spine at the navel. "By that, the lower winds move, causing a fire to blaze up [to ignite this fire] below the navel in a shape like a porcupine's quill". So the flames are lighting up now like a porcupine's quill. "Breathing again makes it blaze up to the navel.

"At the third retention of the breath it arrives at the heart and its heat causes drops", these nuclei, "from the ham letter in the head to fall like a string of pearls. Imagine these drops striking the fire at the heart with a sizzling sound. The fire does not go out, nor does it flicker -these profound points are very important". Thangtong Gyalpo goes on and says, "through this

process, first warmth will arise, then bliss, then the meditative absorption of bliss- emptiness". Here, in a slightly different system, we have a model in this illustration here from the Six Yogas of Naropa of these syllables at the chakras, as mentioned, the flow of these three channels from the base of the spine up to the crown of the head, and you see the network of the subtle body here and it's kind of anatomical structure as induced by tummo. Yogic heat is induced through sequences of breath retention and forceful breathing, physical exercises, moving and striking the body, and visualization. Practices of tummo induce thermogenesis, that is to say, the process of generating bodily heat without shivering, and the typical bodily mechanism for thermogenesis is to shiver. If you get cold, in extreme cold the body shivers to generate heat. Bodily heat is a symptom of the practice, however, it is not the purpose of the practice per se.

The purpose of the practice is inducing yogic heat to experience the warmth of bliss fused with emptiness. Now we have a famous poem by Milarepa who finds himself in a blizzard climbing the slopes of a mountain in which he finds a meditation cave and describes the size of the snowballs like cotton balls falling from the sky, and the winds blowing, and he describes this experience that he has at Lachi Mountain in western Tibet as being a frigid blizzard in which he finds solace in this mountain, and then he generates this inner heat of tummo to keep his body warm. It's important to keep in mind that we have these poems and sort of autobiographical accounts of yogis generating heat to keep themselves warm in the frigid cold of the Himalayas, however, the purpose from these teachings is not warmth per se but this experience of induced blissful warmth. These practices of tummo are historically practiced with sexual yoga in some tantric context, and we'll often find tummo and sexual yoga described together in the meditation manuals. There are debates and divergent views about whether a yogin engages with an actual or an imagined consort, and this goes back at least to Naropa, who in his commentary called the Sekkodesha on the Kalachakra he is making reference to whether you use an actual consort or an imagined consort in these practices and associated sexual yoga practices.

Tummo mimics the intense blissful excitation from sexual orgasm but redirects experiential flows of orgasmic bliss to stimulate a state of bliss infused consciousness. Physiologically sexual intercourse redirects blood flow from the genitals to increase blood flow in the brain. Interestingly enough, a similar hemodynamic paradigm is at play in the performance of tummo. So we find here a kind of parallel paradigm between tummo and sexual yoga, as far as the blood flow from the brain to the genitals. Here's a wall mural, the Lukang in Lhasa, adjacent to the Potala Palace, in which we have a depiction of a yogi practicing these subtle body somatic yogas of generating heat. Tummo in the modern imagination emerges in the early 20th century, and we have this figure, Alexander David-Neel, who is a Belgian-French explorer and author of numerous books on Tibet.

She traveled extensively throughout Tibet, sometimes disguised as a Tibetan nomad. Between 1912 and 1916 she learned tummo from Lachen Gomchen Rrinpoche and practiced in a cave in Sikkim, so she actually practiced these under the supervision of Gomchen Rinpoche. In 1924, Alexander David-Neel was the first European woman to visit Lhasa when foreigners were forbidden there. In 1929 she published "Magic and Mystery in Tibet", originally in French and soon after translated into English, that described tummo and other yogic practices as "psychic sports" and "breathing gymnastics". In her description of tummo as a breathing

gymnastic or psychic sport she writes, "upon a frosty winter night, those who think themselves capable of victoriously enduring the test are led to the shore of a river or a lake. If all the streams are frozen in the region, a hole is made in the ice. A moonlight night, with a hard wind blowing, is chosen. Such nights are not rare in Tibet during the winter months. The neophytes sit on the ground, cross-legged and naked. Sheets are dipped in the icy water, each man wraps himself in one of them and must dry it on his body. As soon as the sheet has

become dry, it is again dipped in the water and placed in the novices' body to be dried as before. The operation goes on in that way until daybreak. Then he who has dried the largest number of sheets is acknowledged the winner of the competition". Now this sheet drying competition as she says is not a myth or something that she made up or imagined, there are sheet drying ceremonies in Tibet, they go on to this day. Here's a photograph of one happening at Nangzhig Monastery in Tibet, and this account by Alexander David-Neel really set the stage for associating tummo with sheet drying and this sort of extraordinary phenomenon.

You find different expressions of this within popular culture. For instance, here we have a cartoon, the first slide reads "when you are able to dry these wet robes with only your own body heat, return to me", the teacher says to his novice disciple. In the second frame the disciple goes off with these wet sheets, wraps himself, you see the steam start to rise off the body of the meditator, and once he's dried he brings it back, and in the third frame we have the disciple giving his sheet back to his teachers and his teacher responding "you are ready", and the final frame, the punch line is you can go to the laundromat for 25 cents a piece for the monks to dry your laundry. So we have these popular depictions and popularizations of tummo, and starting certainly by the 1920s and 1930s with Alexander David-Neel, Evans-Wentz translates some works that include tummo, and we have now popularizations of tummo where people are practicing tummo or practicing derivatives, claimed-to-be derivatives of tummo.

If you go for instance to YouTube and and put in the word "tummo" you'll find all sorts of practices and instructions by all sorts of folks who are eager to teach tummo. One of those associated with this has become Wim Hof and the Wim Hof Method. However, on the Wim Hof method web page they have a disclaimer that says, "some people say Wim Hof is a practitioner of tummo, but the Wim Hof method and tummo are comparable but different techniques". So here you have a clear distancing, yet close language saying that they're comparable yet different. You will find certainly

students or people who have studied with Wim Hof making claims that they're teaching tummo. So I now shift to the scientific research that's been done on tummo, and we have several cases. This begins with Herbert Benson's research, who's a cardiologist at Harvard University and was one of the first scientists to seriously study meditation, and began with studying T.M or transcendental meditation in the 1970s and then the first really to study Vajrayana contemplative practices. In 1981 he conducted the first study of Tibetan monks practicing

tummo. The study demonstrated intentional regulation of body heat for the first time. Two of the three Tibetan tummo practitioners in this study demonstrated activation of the sympathetic nervous system, evidenced by increased metabolism and oxygen consumption, and at this time this was a radical breakthrough of understanding that there can be volitional or voluntary manipulation and change of the sympathetic nervous system. Kozhevnikov, Maria Kozhevnikov and her colleagues in 2013 conducted another study that found tummo increases core body temperature and elicits an arousal response, again confirming the findings of Benson. They measured tummo practitioners to voluntarily raise both peripheral, that is to say, heat on the fingertips and in the toes, and core body temperature. The study demonstrated that activity of the sympathetic nervous system significantly increases. Thermogenesis induced during tummo raised body temperature above the normal range into the fever zone, that is to say almost 101 degrees Fahrenheit, and if you see the chart here, it's really off the charts, the body temperature. Visualization is found to be critical to override

the threshold of the fever zone, and this is a very interesting finding by Kozhevnikov et al., that practitioners can raise their core body temperature to the fever zone without visualization and only breathwork, but can only override the fever zone with visualization. So this shows influence of the kinesthetic imagery and the cognitive mechanisms underlying the practice, that it isn't mere manipulation of the physical body but that there are these visual and cognitive dynamics at play that are just as instrumental and influential. There are stunning differences

between those who have practiced tummo under cold exposure and those not practicing tummo. In particular, profound vasa, or blood vessel dilation, and blood flow to different organs, profound increase in cerebral blood flow, which is a significant marker because cerebral blood flow usually doesn't change dramatically except in shock states. For instance, you can stand on your head for significant duration and there will not be dramatic change in blood flow to the head or cerebral blood flow. Drying wet sheets, practitioners showed vasa dilation indicating hot internal blood flow to peripheral body and brain. It is an open question however, I'll contend and would like to pose as a kind of worthy experiment to scientists interested in this, about whether brain regions activated during tummo correspond to the same brain regions activated during sexual orgasm, and we've made the correlation or have observed the correlation made within the literature and the tradition between sexual yoga and tummo, so it's an open question whether there are correlations in the brain. The redirection of blood flow may direct blood to different regions

of the brain such as the prefrontal cortex or other regions associated with enhanced cognition. So in conclusion here I'd like to talk and reflect about working with technologies of breath, and summarize some of the points here. Breathing techniques including breath retention, forceful and gentle breathwork, ecstatic breathing, and so forth are integral to Buddhist contemplative practices. The context of tummo practice is a broader contemplative practice curriculum of Vajrayana completion stage yogas that cultivate complementary skills of attention, imagination, embodiment, that is to say, tummo and these other associated or affiliated practices are embedded within a larger curriculum and context. Numerous derivative practices and popularizations have emerged about tummo in the modern Buddhist imagination and popular spirituality over the last century.

This is not limited to North America, but I would argue is a global phenomena, and many of these have origins in the sensationalization of tummo starting in the early 20th century. Research shows tummo can be a kind of intentional shock method to the body that activates arousal of the sympathetic nervous system and increases cerebral blood flow. However, this can be injurious. It may even cause death under certain conditions, that is to say, one must be wary of practicing tummo unless it is under the supervision of an experienced practitioner, that one does not go off like a rhinoceros, so they say, to practice tummo. Future research might elucidate further what brain regions light up and where there is increase of blood flow, which studies have not measured well to date.

So with that I'll share some recommended readings, also sources that I've cited throughout this discussion today, and my own contact information if people would like to get in touch with me with questions or have discussion, I'm most open to that. So thank you so much.

2021-09-08