Technology to Improve Maternal Health: Facilitated Discussion—Community

Okay, hi everybody. Good afternoon, everyone. Glad that everyone was able to stay and hopefully you are able to come back for the next panel. I'm just gonna briefly introduce our moderator for the next panel, which is gonna be a facilitated discussion on community. So our gracious moderator is Dr. Joia Perry,

and she is a physician, a policy expert, and thought leader and advocate for transformational justice. And she also is the founder and president of the National Birth Equity Collaborative, where she identifies and challenges racism as a root cause of health inequities. And as you can see from her shirt, she's very passionate about this.

And so with that, I'm gonna pass this over to Joia. And if you can come on camera and, obviously, unmute yourself, I'll let you guys take it over. Great, hey y'all. Thank you so much, Jamie, for having me, and thank you, if I can have my fellow co-panelists come on the camera and unmute themselves, as well. So first, it'll be Dr. Tonya Corbin from Organon

who's joining us and the bios, the longer bios, are in your booklets for these individuals. Also Dr. Nathaniel DeNicola, who is actually also a Tulane OB-GYN grad, along with me, so that's super exciting to have another TOGAS person on the panel. Dr. Gerald Harmon from American Medical Association, Dr. Natalie Hernandez from Morehouse School of Medicine,

Dr. Monica McLemore, who's currently at UCSF, and last but not least, Dr. Steve Porter from riskLD. Next slide please. So to set the tone for our community conversation, I'm just gonna take about 10 minutes to talk a little bit about our work and about the importance of ensuring that equity and anti-racism and anti-oppression are embedded in whatever technologies you do, especially when we're wanting to improve birth outcomes and maternal health in this country and around the world. Next slide please. So our organization is almost seven years old.

It's kind of crazy, time flies when you're having fun. We were originally founded to work on black infant health, because although I am a 50-year-old black woman in a 50-year-old black woman's body, like most of you, we focus so much on the baby, baby, baby, and ignore, as my good friend and colleague Dr. Stuebe would say, the wrapper around the candy, right? So a person has a baby and we're so excited about the candy and we just throw the wrapper away. That's how we've treated maternal health from the beginning. And so it's important for us to really ensure that the whole full life course of a person with the capacity for pregnancy is seen as valuable.

And so our vision is that all black mama's babies and their villages thrive. So that means really thinking about technology through the lens of the village and incorporating the needs of the village in your work. Next slide, please. Next is clinical, as an OB-GYN we know that 90% of the outcomes were not based upon that 10 minutes or 15 minutes that someone has in the room with me or anything that I put in on an electronic medical record, but really their entire social world, that mixture of both this clinical and social, is the focus of our organization.

So that means we have to be honest and talk about the importance of dismantling systems of power and racism, educating ourselves on the social determinants of health inequities. Next slide, please. When we started our organization, there was not a definition for birth equity. There were definitions for health equity or equity in general. We talk a lot in the space of health and healthcare of equity as a place, we're gonna get to this place and everybody's equal, we can hold hands, sing Kumbaya, dance into the sun, and everybody's happy.

But we know, especially in our current political environment, sometimes we get a few steps forward. other times we're going 10, 5, 6, 7 steps backwards. So it's not that we're gonna get to this magical place and we can all relax and just drink milk and honey. But that all of us, that the people who are currently hoarding power and wealth are teaching their grandchildren how to hoard power and wealth.

So if we want to have justice and joy for all people, we have to teach our grandchildren to fight for justice and joy, and put together today the assurances, the policies big "P," things like Medicaid expansion or policies little "p", like how you decide to include people of color when you are creating whatever technology you're creating to improve their outcomes. Who did you ask of what they needed and what they wanted? Those kind of assurances for the conditions for optimal births. We don't want people in the United States and around the world to just survive a pregnancy. We want them to thrive, to live their best lives, to say, "That was amazing, I feel nurtured, I feel loved, I feel seen, I feel valued."

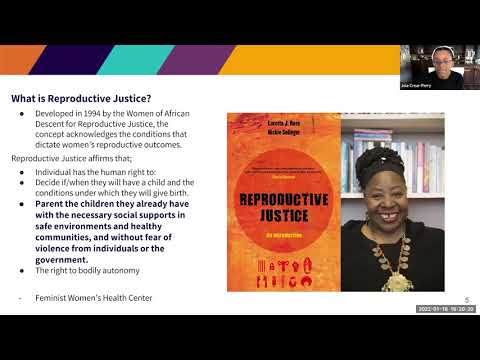

So that means we, all of you, have to be willing to address both racial and social inequities in a sustained effort. A two-year grant cycle, even a five-year grant cycle is not gonna fix what took us 400 years to get here. We're deeply invested to undoing the harms of racism, classism, and gender oppression, together. Next slide, please. So about 30 years ago, there were a group of black women who were having this, in a similar moment, this idea of, what would it look like to have reproductive justice? Reproductive healthcare is what we provide as OB-GYNs, as midwives, as nurse practitioners. And those are the things like pap smears, hysterectomies.

Reproductive rights are the laws and the policies that dictate how we get to do those things. But reproductive justice is a vision. It's a framework for how might we undo the harms of eugenics, of population control. That means we must first be truthful about knowing that the harms of eugenics and population control are still operationalized in our federal, local, and international policies.

But back in 1994, women of African descent really created this framework for reproductive justice that states and affirms that individuals have the human right to decide if and when, all individuals have the human right, let me say. no matter their color, their geography, their income, or their gender, their sexual orientation. All people can decide if and when they will have children and the conditions under which they will birth.

And they are able to then parent those children with the necessary social supports. And that's where you all can come in. What are the social support that ensure that they have safe environments, healthy conditions, without fear of violence from individuals or the government, and then lastly, but most surely not leastly, that we have the right to personal bodily autonomy, that we control our bodies, ourselves, and our choices, and our decisions.

Next slide please. So we were honored to be a part of the Maternal Health Access Project, which was funded through the Cares Act, under the previous administration, where we really were looking at what quality and respectful care throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period were critical to ensuring the health and well-being of all, looking at COVID-19 as social distancing restrictions having disrupted access to essential and wrap-around services and care, with increased risk for adverse events for people of color. And then lastly, telehealth and other forms of remote services are promising as means to improve equitable delivery of care to communities in the greatest need. Next slide, please. But these are some finding from focus groups with black birthing individuals and black birth workers around how technology is impacting them.

First, it was impersonable from the black birthing people. It was diminished quality of care. There was a lack of equipment, lack of things like blood pressure cuffs. Who's working on that issue? As you all are doing these technologies, well, we needed some blood pressure cuffs.

Who's working on that? Dopplers, communication and technology barriers, navigation of in-person visits, including labor and delivery without having any support, without having not only a partner or a doula, and then having to fight for and advocate for proper care in the middle of a pandemic for themselves and their families and their babies. What about the black birth workers? They had to advocate for doula services during the pandemic, being able to even be seen and allowed into the facilities, navigating the lack of compassion, the lack of emotional intelligence was mentioned in the earlier talk. Who's working on cultural humility? Not competence.

I can't be competent, I can't check off a box that I've learned everything about all of your cultures, but I can be humble and spend my life with lifelong learning about other cultures and ensuring cultural humility among non-black providers. Shifting our outreach strategy, limiting the scope of practice due to virtual care, navigating digital redlining, right? We know that broadband is as issue, not just in rural America where I grew up, 'cause rural is very diverse, but also urban America. There's deserts for having access to broadband across the United States. And that's a policy choice that we can do differently and really expanding the reach of their services. Next slide, please.

So what are some of our recommendations? Provide birthing individuals with WiFi hotspots, electronic devices, equipment like blood pressure cuffs, and training to participate in telehealth. Respect patient autonomy and offer hybrid models. If people wanna come in person, respect that.

If they wanna do telephone and not have the video on, respect that. Integrate telehealth into patient records and automate so it prompts for direct referrals. That is the gap, the silos. Prove to me why it would be better for a patient to come have a baby in a hospital if none of your systems speak to one another and none of them prompt to have any kind of social services referral. What is the benefit of being in that space? Educate providers about quality and respectful maternity care, undoing the harms and legacy of racism, classism, and gender oppression. Provide birth workers with a livable wage.

We are so worried as we feminize the field of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Most things, when they become feminized, they become devalued and they become less. People are not given as much resources, that happens from OB, birth workers, across the field nursing. How do we ensure that people have a living wage, subscriptions for virtual platforms and telehealth tools? And then last, but not least, invest in black birth workers and community-based black women-led organizations that have the greatest impact and expand the provision of maternity care services to populations lacking access. Next slide, please. And that is it, with that, thank you.

We will move on to my colleague who will begin his presentation about riskLD, Dr. Steve Porter. Can you join us, Steve? Thank you so much, Dr. Joia Crear-Perry. And thank you so much to the NIH for organizing today's riveting set of discussions.

I believe I have some slides and if we could go to the, the first slide, thank you so much. So by way of brief introduction, I am Dr. Steve Porter. I'm a practicing Obstetrician-Gynecologist based at University Hospital's Cleveland Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio.

I would also like to disclose that I am the CEO of riskLD. We are a patient safety solution, a software that provides a combination of early alerting and clinical decision support at the point of care on labor and delivery. Next slide, please. We are all acutely aware of the numbers and of the yawning racial disparities in maternal health outcomes. What I'd like to focus on is the subset of these adverse outcomes that occur during the inpatient episode of care, because that's really where our software solution is focused, is mitigating hospital-based severe maternal morbidity and mortality.

When we take a step back and we look at what's driving these adverse outcomes and we contemplate the availability of clinical best practices and maternal safety bundles, and we think, "Well, what's missing? What is driving these adverse pregnancy outcomes?" Next slide, please. When we think about what's missing, we feel that part of the answer is technology. And, of course, that's what's bringing us all here together today. What we've developed at riskLD is a software platform that fully integrates with and is actually delivered through the inpatient electronic health record and provides a combination of early warning and clinical decision support at the point of care on labor and delivery and postpartum. So our software does four things. It monitors mom and baby continuously, and that monitoring starts from the moment the patient arrives on a labor and delivery unit and continues until the patient is discharged from the postpartum ward.

So continues the patient for the duration of that inpatient episode of care. The system will suggest diagnoses to consider, in real-time. It will push alerts about the presence of those high risk conditions. And then lastly, it will issue real-time, evidence-based clinical decision support for how to manage the condition that has been identified.

Next slide, please. There are two main views of our software. The first is what we call the global or unit level view, which provides a snapshot of all of the patients who are on the labor floor at a given time, and it pushes alerts to indicate the patients who might need extra attention. These are the patients who have abnormal vital signs, who are manifesting high risk conditions, or whose labors are not progressing appropriately. This is a tool that's used by the leadership of the unit, whether it's the chart nurse or the attending physician, to identify problems and to allocate resources accordingly. Next slide, please.

Clicking on one of these individual patient windows will pull up the next view of the software, which is the patient-specific view. And this provides an integrated view of mom and baby. Essentially what we've done is collapsed all the relevant maternal information and all the relevant neonatal, or rather, fetal information onto a single user interface and we've engineered it so that trends can be observed over time.

You can see how the fetal heart rate baseline is changing over the duration of the interpartum course, how the labor curve is progressing. We see every vital sign from the moment the patient arrived on labor and delivery. And the software is pushing alerts to indicate the presence of certain relevant intrapartum events or conditions. Next slide, please.

So we can make this real with the example of pre-eclampsia with severe features. This is a clinical condition for which we can set objective diagnostic thresholds based on blood pressure levels and evidence of end organ dysfunction. So the way it works is when a patient is meeting diagnostic criteria for pre-eclampsia with severe features, again, based on these objective diagnostic thresholds that have been set, the alert is fired, and within the alert is an evidence-based management pathway for how to manage that condition that has been identified. Next slide, please. Within these alerts, we also have links to ACOG guidance on particular topics.

So if we take this particular example, an alert for intraamniotic infection, not only only do we have a checklist for how to manage that condition, for what antibiotics to start and when, we also have links that can bring the clinician who's working at the point of care on labor and delivery to relevant, targeted ACOG guidance on that particular topic that comes from the relevant committee opinion or practice bulletin. Next slide, please. Our software can also be used to issue real time reports on indicators, on metrics that are of interest to the hospital or labor and delivery unit. We capture a wealth of data on every patient who is run through our system. over 130 data feeds per patient.

And these pertain to the patient's past medical and obstetric history, every vital sign during the duration of her inpatient episode of care, any lab that has resulted, any medication that she's on, so it's quite a bit of data that we're able to filter and analyze and issue reports against. And those reports can be at the macro levels, such as the rates of blood transfusion or at the very micro level, looking at the time to treatment of severe range blood pressures, or the time to treatment of intraamniotic infection, and specifically, if those times to treatment vary based on the race or ethnicity of the patient. You know, one of the limitations of perinatal quality data is that much of it is retrospective, looking at data from several weeks or several months ago. Really, what we want is real-time reporting, real-time feedback that will inform what we are gonna change on our unit tomorrow.

Many of you may be familiar with the Toyota production system, and if that process for continuous quality improvement can be applied in an automobile manufacturing plant, there's no reason we can't strive for the same on our labor and delivery units. Next slide, please. So stepping back, thank you for this opportunity for sharing more about what we are building at riskLD. Our hope is that this tool, this technology, this software, can be part of the solution for mitigating hospital-based severe maternal morbidity and mortality by elevating the situational awareness of the labor and delivery unit and directing clinicians' attentions to issues that need to be addressed in a timely manner. That's particularly important in the context of COVID-related staffing shortages that have started to hit labor and delivery units, how this tool can be used to automate delivery of clinical best practices.

Now, for many of these conditions, it's not about knowing what to do, it's about ensuring that what needs to happen gets done and gets done in a timely manner. And the last point I wanted to make relates to equity and make no mistake about it, technology does not deliver equity and a software solution like this does not eliminate unconscious bias on the part of healthcare providers. Our hope is that this tool, when used appropriately, can help mitigate racial disparities in treatment, because it alerts objectively, based on objective indicators of distress and forces clinical teams to engage with and respond to those objective indicators of distress, which I think is an important counterbalance against the subjective biases that we layer onto our patients, and that contribute to worsening outcomes for women of color, particularly on inpatient obstetric units. I wanna thank all of my colleagues and all of my co-panelists, and I'm really excited to continue the conversation. Thank you for giving us the opportunity for sharing more about what we've built at riskLD. Thank you so much, Steve.

And now if we could have the rest of our co-panelists, oh great, y'all are off camera, great. And so first off, Tonya, I wanna start with you, as a follow up to Steve's presentation. Just thinking about, as integrated software systems like riskLD are fairly new, what additional technologies does Organon have to provide support in a clinical setting? Yeah, so first of all, I wanna say thank you. And this is a great opportunity to join such an impressive panel. One of the things that we are doing at Organon is first of all, we are committed to the unwavering commitment to drive innovation in women's health. We make us a highly focused company with a clear goal on research and development to better, healthier every day woman.

When we think about technology, we do know as a company we're working on diversifying how people think about women's health, moving beyond her reproductive and her uterus, to ensure the needs of women with different health concerns issues, and to meet unmet needs. So when we think about data, the data is real. When we think about black women, about two to three, four times more likely to die from pregnancy or delivery complications than white women. So as a company that believes in innovation, Organon, we are happy to say, our JADA system is a prime example of how technology and innovation can mean the difference between life and death in a matter of seconds.

The data system was designed to apply low-level vacuum, to encourage normal contraction of the uterus to provide control and treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding and hemorrhage after childbirth. So we are happy to say as a company, after 2000, in October, 2001, the FDA clearly approved our technical update to JADA that includes a new kit configuration, as well as updating the packages and streamlining the design to improve the ease of use of JADA. And so most importantly, we find that as a company, with Organon we are gonna continue to explore opportunities to improve women's health, which includes investing in sectors of medicine, as well as device and technology, to meet all unmet needs.

Next, I wanna turn to my colleague, Natalie, to talk a little bit about Morehouse School of Medicine, one of my favorite places. Healthcare technology's reshaping the healthcare system. Can you discuss the work that you are doing at the Morehouse School of Medicine for maternal health equity, as it relates to the needs for pregnant, postpartum, black, indigenous, people of color individuals? Thank you so much, Joia. Thank you, NIH and panelists for allowing me to talk about the work that we're doing at our wonderful historically black colleges and universities.

So the Center for Maternal Health Equity at Morehouse School of Medicine was established in 2019. As some of you may know, Georgia actually has the worst maternal mortality rates in the country. And our vision and mission is really to pursue equity in maternal health, by reducing maternal morbidity and mortality, locally, nationally, and globally. And our approach includes interdisciplinary translational research at understanding prevention and reduction of these causes, interprofessional training of future leaders across the workforce continuum.

And so we're thinking about team-based approaches to care, outreach, engagement, and education with our community members. So at the center, we provide a lot of technical assistance for communities that are doing already amazing work. And so we provide TA for black-led community organizations. We provide evaluation to build evidence because we know that the solutions are already existing in the community, and we want to support them and not be this academic machine that comes in and tries to overtake what our community members are already doing. We wanna make sure that our research translates into action for communities.

And so we make sure that our community is really informing policy and advocacy. And so we were really instrumental in helping to move the needle and establish postpartum Medicaid extension in the state of Georgia. And we're really thinking about innovative and respectful maternity care. And so we have colleagues that have been developing simulation models and really thinking about communication strategies. We look at all birthing persons from a life force approach, so from preconception all the way to the postpartum period, and one of the things that makes our center really unique than other academic centers is that we really center the experiences of black women and black birthing populations.

This is an opportunity to rethink conventional research practices. We acknowledge that women's lived experiences are legitimate sources of knowledge. And we also ensure that our BIPOC investigators, who look like the community, are leading a lot of this work.

Oftentimes we're brought in, in more of advisory capacity, rather than knowing that we can lead this work. We know our communities, we are affected by the same issues that communities we serve go through. And so right now, one of the things that's with this panel around technology that we've been doing to really address maternal mortality and morbidity and severe maternal morbidity is a mobile app called Prevent Maternal Mortality Using Mobile Technology, or PM3. It's a prevention and optimal reproductive health promotion app based on formative work that we've conducted with black birthing people to increase postpartum comorbidity self-management, promote timely provider notification of postpartum-related complications, and ensure access to social support and community resources. This technology is funded by Johnson & Johnson Health of Women Team within the office of the Chief Medical Officer. And so we're really excited about these opportunities.

As I mentioned, this is a mobile application that was developed and co-created with the communities and birthing individuals with lived experiences, using human-centered design, focused on equity, usability, and user preferences. We've learned early on that everyone wants to address everything and make it complicated, when our woman just want something simplistic, something that really fosters equity, that fosters them to take control, although sometimes they also feel like the onus is always on them. And again, it provides social support, addresses the social determinants of health, allows for meaningful engagement with other moms, communication, engagement, and social justice. For instance, through our mobile application, there's an opportunity for women to register to vote or to learn about different policies that are occurring in their local communities. And so those are a couple of things.

And I know that one of the things that, again, that we found out through our affirmative work is that, they just wanna be heard, they wanna have support. One of the issues we thought going in would be about pre-eclampsia or sort of all of these medical conditions, when the number one priority for our women was maternal mental health. And I heard a lot of people to talk about these things. And then you add the dual pandemics of COVID-19, and this outreach of racism or now racism being displayed for all to see, really exacerbated a lot of the issues and the components that women wanted during the development of the mobile application. So right now we're going into our randomized control trial and integrating different components, including wearable devices.

We receive funding from the Fitbit Health Equity Initiative to have wearable technologies. And so these are a couple of the things that are going on. This is one of four mobile applications that are being developed at Morehouse School of Medicine. Thank you very much for that Natalie, and Gerald, let's move to you. Before the pandemic, telehealth was limited. With a large portion of medical visits now virtual, what physician training is being provided, not to show providers how to use the telehealth tech, but to integrate it into their practices? Dr. Perry, thank you.

Thanks to all of you for allowing us to join. Let me tell you just a quick background on what the AMA is, and I'm the current AMA president. I'm a family physician in rural South Carolina now, almost 40 years, so. I've done this for decades now, and I'm dealing, and I practiced obstetrics for the first 20 or 30 years, including operative obstetrics. We didn't have a lot of obstetricians in rural America, as y'all know. And so I wound up delivering hundreds of babies across all spectra, so part of my lived experience is that I've been in rural America, like many of you, and I've seen outcomes that aren't where we need to be.

The AMA is a representative of 180 different physician societies. In our house of delegates, we represent medical students to senior physicians, to retired physicians, every lifestyle, whether you're a bench researcher, an educator, working for industry, private practice, large group practice, we represent every spectrum in our house of delegates. Our mission, advance the art and science of medicine and the betterment of public health. That's a very high calling, I hope we can live up to it. We have three strategic arcs, keeping physicians satisfied, fighting burnout, sustainability of practices, preparing the workforce for the present and the future, through medical education and career educational opportunities. And then improving health outcomes.

We have three strategic accelerators, advancing and embedded health equity across all of those three strategic arcs using innovation, such as technology, wearable technology, digital medicine, and finally implementing all those strategic arcs with their advocacy levels to implement institutional change, legislative regulatory change at the federal, state, and local level. So we're busy as can be in today's world. You've heard the previous speakers. You've heard our presenter here today, Dr. Perry, talk about the opportunities for improving, the need for urgency, which is now. As far as the telehealth initiative, AMA has championed telehealth expansion from the get-go, it's something we were thinking about before we had the COVID pandemic, the COVID pandemic allowed us then to allow our communities to un-shutdown, AMA saw that we were shutting down opportunities for visit.

And so we, we saw it as a potential lifeline for practices as well as for patients. We've advocated and we've been able to secure, with the help of other collaborators, broad telehealth expansion, improve payments, including non-visual, so that you can just get a telephone call and take care of your patients. They can call you from the comfort and safety of their own homes, and that's accountable, that's reimbursable. We know it costs physicians money to do all this stuff.

The studies show that in order to keep it sustainable, to keep it equitable for our patients, we need to make sure that our practices are allowed to bill for those services, and thank goodness the administration and the government has allowed that to happen, we'd like to see that happen. We've got a bunch of free online resources, were gonna teach our doctors how to do it. We know from our studies that 68% or 70% of the patients like telehealth, 75% of doctors think it's a good way to provide quality care, so everybody's supporting it.

We need to give them the resources as you talked about, Dr. Perry, to make sure they're trained to do it. So we have online resources in an online digital world. Those that wanna do it can get online, the doctors, the healthcare professionals. It's free, we have a Steps Forward module, we have telemedicine online, we have best practices that we've shared with each other. We've worked with a couple of state medical societies to establish what's called the Telehealth Initiative.

We believe this is incredibly important for us, and we are learning to use these tools because as you indicate and many other speakers before me, we wanna make sure that when our patients, when they connect with us through digital method, they can trust us to listen to them, to provide quality care. And a point I also heard, that we can offer them a hybrid solution. We don't only relegate those, our patients, our vulnerable patients, to telehealth, you can come on in and see us, too. We're trying to keep our practices open, to make sure that quality care can be in-person care. I can go on and on, we've got a lot of speakers, but I'll be glad to answer individual questions.

And I thank you again for the opportunity to start talking today, thank you. Thank you so much. I appreciate you always. And now to my fellow TOGAS member, Nate, let's talk a little bit about, we've talked about the new technology and all the amazing things it can do, but what is your perspective of clinical integration of technology and clinical oversight to improve linkages to outpatient care? As well as you can talk about the American College of OB-GYN and what they're doing.

Well, thanks Joia. Yeah, the Tulane alumni society is gonna have a high bar to clear for the next event, after what you organized here. So in the role with ACOG, and this is not officially published anywhere, but this is how I've always approached these new technologies.

For the perspective, I kind of am guided by these three P's. And the first P is permission. ACOG can provide its blessing and give its membership permission to begin using some new technology with the caveat that it comes hand in hand with the second P of protection. The protection is the result of rigorous scientific method applied to evidence-based medicine and kind of deeply thought out methodology to provide some best practices.

And so that the protection is both for the providers, so they have some kind of parameters and guardrails for where they can use this new technology, but also for the patients, so they're not gonna suffer any predictable adverse outcomes from the new technology. And then the final P, which is where I really wanna spend some time, is the promise. And the promise is when you can optimize the benefits of a new intervention while protecting yourself from known pitfalls and minimizing unknown, unintended consequences.

And the promise with telehealth is that we can really modernize healthcare to be optimally adaptable to time and place. So we can get patients to care when they need it and where they need it. And I'd say, access is built into both of those, but the "where" really becomes critical to access for a lot of the communities that we're working with, who don't have 24/7 availability to get to the hospital as quickly as they might want to, or who need the care in after hours and who need increased connectivity with the healthcare system that historically might not have been available. So that "where" has been a huge focus of the telehealth interventions.

Now, the way ACOG specifically dealt with these, what I'm calling the three P's, was through two documents which published in The Green Journal in 2020 in February, we couldn't possibly have predicted it would be on the cusp of a global pandemic, but nonetheless, that's when these publications occurred. The first was a committee opinion. This was affectionately called the "How-To" document in development, and it basically was providing a lot of these protections. So it went through licensure, billing, credentialing, how to not break laws by providing healthcare across state lines, kind of all the nuts and bolts you would need to implement telehealth in your practice. We affectionately say that it takes about 17 years for full adoption of a new ACOG Committee Opinion, I think this one took 17 minutes, because by the time it was published in February to the pandemic kind of massively affecting healthcare delivery in April, the document was almost kind of obsolete or at least, it had been adopted. But the second document was the Systematic Review, which I can spend a little bit of time talking on with the specific questions.

But basically we applied rigorous scientific method to a number of new telehealth interventions, primarily virtual visits, patient-generated data, connected devices, verbal devices, and how they could be used in what we defined as the four domains of our field, low risk obstetrics, high risk obstetrics, outpatient gynecology, and family planning. And the theme among all these was that the studies that met our rigorous inclusion criteria passed a non-inferiority standard, meaning the telehealth intervention was no worse than standard of care, but it offered other benefits such as being more highly accessible, or having higher patient satisfaction. And that was true across, say, providing glucose control for diabetic mothers, as it would be to providing long-acting reversible contraception counseling to people who couldn't get to the clinic as readily.

And so that's the foundation that ACOG built on during the pandemic. Of course, you know, as things rolled out, we sort of adapted guidelines to be more tailored to an emergency pandemic where even if we didn't have the same scientific rigor of a systematic review, we could allow best practices to do things like, say, adapt the annual wellness exam to a virtual visit, where you could do say 80% of it without the patient coming in person, and then tailor in-person visits as needed. So there's a lot more to talk about there, but I know we've got a lot to cover. So I'll kinda save that for Q&A.

Thank you so much, Nate. And now, last but not least, Dr. Monica. And how do we ensure that the U.S. healthcare algorithms for reproductive health are working to benefit and not to harm or exacerbate inequities in maternal health outcomes? Well, thank you, Joia and the entire team for having me. Thank you panelists for setting me up really well.

And thank you to the 155 people who are still on here. I have to tell you, I logged in this morning for Elizabeth Howell's keynote, and you all have been in this for a long day. So thank you for sticking around. That said, I've had an opportunity to pop in and out of different sessions, whether it be Dr. McNamara talking about

the incredible pregnancy complications and treatment of RCT, hearing Dr. Byatt talk about apps, registries, and mental health and realigning mental health and physical health, to hearing about mass spec and CRISPR and a whole lot of other technologies. And I wanna make three big points. My first point is I wanna say the words, midwives, doulas, nurses, public health lawyers, and the whole rest of the team-based approach is because I do feel like the humans behind the technology are just as important as the technology. And I say this as a long-time registered nurse, who's been continually licensed since 1993.

And I can tell you things like alarm fatigue and many of us who are clinicians know that we've seen pulse oximetry that's zero and a patient is sitting there talking to us 'cause it's not on her finger, right? So we think about the human error that's behind the technology. And so without really appreciating the team-based members and the humans behind the technology, I think we miss a crucial point of this meeting and that's to talk about how are we gonna shore up those individuals? I think it was Steve who said it best that technology doesn't necessarily ensure equity, and that we have to really be thinking about the humans behind the technology. The second piece I'll say is this, I mean, we've heard a lot about access, but I would like for us to have more discussions about the unintended consequences of surveillance and profiling, right? Technology is a tool, how it is used is determined by its users. And so at some point we really have to think about, do community want all of their information displayed for all to see without their consent, without their permission, without knowing, and without their own inputs, right? I have yet to hear anybody say patients should be documenting in all of this technology, in addition to our contributions as clinicians and researchers. So where's the community portals so they can input their own thoughts or their own data, right? The last thing I will say is this, I want us to really wrestle with whether or not tech has become a firewall for our inhumane work environments.

And so I have data and other people have data that suggests that people like the convenience of telehealth because it helps to resolve some social determinants like transportation or long wait times and waiting rooms. But at some point we also should wonder is technology a protection from the implicit and explicit bias that people have to experience when they come into our institutions? Is it helpful for people to know that they can get on the call and get on a telehealth visit and dictate what that visit will be, as opposed us to having to respond to the information that we want to elicit from them. And so for me, the way to do that is to ensure the community is not only accountable and beta testing and helping to develop said tech, but there are clear ways, on the user side, that individuals can get feedback, real-time feedback, not only to us and the developers, but also to the clinicians and to the researchers and the teams of people who are using these tools.

So two-way street, we need community-generated big data where they can also include their own inputs. I can go on my health app on Apple and put my weight in every day, right? So we are the community on ramps to input into some of this technology. And then where do they get to help design and deploy and to test these different pieces of technology? Those would be the pieces that I would want to move our conversation toward. Thank you, as always, Monica.

And so that reminds me though, I did a panel with this president of, I think it was Howard Med School, last week. And we talked about how, when I started medical school, we started with the standardized patient. And it was this idea that there was this one individual, and you could just practice on this individual, versus the idea of following a family as a first-year medical student for four years, and how the fundamentally different orientation of the belief system of someone who would build a system that said, all we need is a standardized patient, and we can teach people based upon this standard, versus saying, we really need medical students to follow a family to see the impact of their growth and their change over time, to see what happens in their communities, to see when children grow up or move. And so that's the difference that I'm hearing you describe, Monica, that the technology, the orientation to the technology, being one of community, and that's what this community panel is about. How do we ensure that our technology is oriented to the community and does not actually increase or cause harm.

And with that, Steve, with the increase of this kind of surveillance technology available to clinicians, how does your organization balance this need to be responsive to indicators of concern while not leaning into over-medicalization or over-intervening? It's a great question, thank you. And I will build on Monica's point around alert fatigue, which is a phenomenon that we are all, all of us who worked in clinical settings are acutely aware of and sensitive to, because alert fatigue can often create the opposite of what you're trying to achieve, in that you start to... You wanna turn the system off or you wanna ignore it because you're not trusting or appreciative of the information that is being displayed to you. The way we do that is working very closely with our hospital, our clinical partners, to figure out what is the information that they really want to know? What do they want to be alerted against? And so everything can be customized for an individual labor and delivery unit. Some academic medical centers will say, "I don't need to be alerted to the presence of severe pre-eclampsia.

I manage it all day, every day in my sleep. What I wanna be alerted to are some of these early warning signs of sepsis," because often these are not detected or attended to till much later in the course. So that sort of level of customization and providing that end user input and feedback in the design of what is gonna be alerted, so that we strike that balance to what do the clinicians need to know and not over alerting. But I think there's another point here where I'm thinking about how we are gonna take this technology forward.

We've been so focused on end user-focused design, meaning soliciting input from OB nurses, midwives, OB clinicians. But where is the voice of the patient in the design of this kind of tool? What information does the patient want to be displayed about her? What information does does she want you to be alerted to, right? We might think, clinically, "This is what I need to be alerted against," but what does she think we need to be alerted to? That's a really important conversation that we need to have. Thank you so much for that, Steve. And I appreciate your response. All right, so Tonya, as a global healthcare company, what is your perspective on how technologies such as JADA can improve maternal health outcomes around the world? One of our goals with this new JADA device is, the purpose of it was designed to, to apply low-level vacuum, to encourage the normal contraction of the uterus, to provide control of abnormal bleeding and hemorrhage after childbirth. As we know, the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony has increased significantly over the last years.

So as a company, we have our ears out, we have our commitment, we're trying to hear the needs of the physicians, of the patients, and really find strategies or sectors in which we can improve medicine, devices, and technology so that we can meet those unmet needs, so that we can decrease the risk of increased maternal death among all people globally, not only here in the United States, but across the board. So we're constantly trying to move the needle in regards to understanding what the physicians need, what the patients need, how we can bring those together and deliver it as a company. Natalie, how are those needs informing...

Mm, I guess I need to see, I don't have this question written down. What technologies are truly needed and how to combat the inequities in maternal health? I guess, the technologies that you all created at Morehouse. Yeah, no problem.

Thank you, Joia. And so I think a lot of what we used to inform our technology was through formative research, not with patients and birthing individuals, but also, Monica mentioned doulas, different types of healthcare professionals, not just physicians and then even support persons. So fathers, partners, others that would be involved in providing care or assisting birthing individuals with that care. What we heard from a lot of our, when we did the formative work was that people wanted something that was personalized to them. They wanted something for us, by us.

They wanted to see images and bodies and things that looked like the person, they wanted access to community resources that were localized, not just general, to their communities, linkages to support for mental health. They noticed that there was a lack of support between discharge and first appointment, and so they wanted that information because with our mobile application, it's focused on the postpartum period. And then there were issues, and this was brought up, too, issues of mistrust. And so how are we handling information? Who has access to it and how can they vet the information that gets out there? And so these were considerations and things that we developed within our mobile application. It was sort of all over the place, but as I mentioned, the common themes were related to that.

And then the social justice perspective, as well. Oftentimes they feel like they're the last to know, like a lot of women still didn't know about postpartum Medicaid extension or Medicaid disenrollment and what was happening. And so, what are the things that they need to help inform them? I think often times we wanna be so innovative that we forget about the building blocks and the education and resources that birthing individuals need. And that's what this mobile application is intended to do.

It's not to be complicated, it's not to address some of these long-standing root causes, it's helping to mitigate a lot of those barriers through this technology, but really be something where it's real-time, where we continue to give feedback for the people it's intended to serve. So I think that's what makes it unique and why it's really informed by the people. Gerald, Dr. Harmon, hope we didn't...

Oh, there you are, yeah. So follow-up question for you, thinking through the training and the work that you all have been doing there at the AMA, have you seen what this learning process could look like or what some of the successes or challenges that you have encountered in your career? Dr. Perry, I'll put in the chat here. Let me see if I can manage to do that. I'll put in the chat a link to what we're doing at the AMA. Let's see, send it to everyone. I mentioned, to some degree, our Digital Health Playbook, and we've done that.

And I mentioned, we've done a lot of online stuff that we're trying to teach our physicians and our students and young physicians in practice with. I can tell you my personal experience, I'm a clinical preceptor. Y'all don't know what clinical means, it's an additional duty where you volunteer to precept in our Family Medicine Residency. We just are finishing our fourth year, so we're still new at the Family Medicine Community Residency, but part of it is Maternal-Fetal Medicine and maternal health. So we're teaching our resident physicians, and I've tried to use part of this Digital Health Playbook, as well as what we call the online Steps Forward modules that have individual, menu-driven choices about how residents can learn.

And young physicians-in-training can use digital health in their day-to-day practice and in learning how to do it. But I tell you, it's part of being a continuous learning organization. I've gotta confess, I've learned more just sitting here listening to you, Dr. McLemore, Dr. Porter. Now you've made me think. We're doing all this stuff, this more top down, where I'm telling the resident physicians and our digital technologists, "Here's what we need to do," to design what we think we need, from our perspective, to provide quality care out in rural areas of South Carolina.

But I don't know that we are embedding as much as we ought to, and I'm gonna take away from this and be continuously learning and hope, giving you an actionable item on how we can then think about it from the patient perspective. You know, everything we say, we give lip service to "what's the patient think," but to really implement it in an executable form, in an accountable form, I'm gonna have to take that away and take that back to my colleagues at the AMA, not that they're not already doing it, but I can't give you specific answer how I've had patient input and what that module ought look like. I could tell you, we're advocating for just using the phone, I talked about that, 'cause not everybody has broadband in South Carolina, we're working at that at the federal level, advocacy. They can pick up the phone and call us.

I make sure that our providers know to call them back, answer the phone. First, somebody's gotta be there, but I think it's a good idea to see how we can interface with the questions they want to present and what they want to share with us so that they establish again, that bond of trust that we have to do so we could have meaningful two-way communication and deliver equitable healthcare in what has been, historically, inequitable care. Thanks. Oh, that's beautiful.

And honestly, Gerald, that's the Monica effect, that's what I call it. She did that to me when I first met her, she was doing a presentation-- Well, thanks a lot (laughs). She taught people in the community how to review IRBs, and so they had equal power in reviewing the IRBs as the academicians. When does that ever happen? Like that does not happen, okay (laughs)? Amen, Monica, amen, doctor.

I knew from then that we were gonna be long-time friends, that was gonna happen. All right, Nate, next up is you, I think on my little list here, yep. What are some telehealth services and strategies that have and can improve maternal health outcomes and the policy implications associated? Well, Joia, talk about being the queen of segues, that ties exactly into the next topic that I was hoping to discuss. You know, I think there are a lot of clinical outcomes that can be studied and we will eventually have enough data to say we'd improved an outcome.

Of course, that's a really high bar to say, we actually provided this superior outcome. Postpartum blood pressure monitoring, for example, has already shown that we've transformed, in some small ways at least, the postpartum period, from a kind of, as you're going out the door, "Congratulations on your baby, we'll see you in six weeks," to now more of a continuum where there can be short follow up in one week, two weeks. But beyond the clinical outcomes that will show a superiority kind of standard in data, I think there's lot to be said for the other outcomes that occur within the non-inferiority studies, things like increased patient engagement, satisfaction, bidirectional flow of information.

And just some examples, when the Reach Project did their survey of their patients through some telehealth methods, they found that up to 20% didn't have any education about the extra risk of their pregnancy due to some common conditions like anemia, like high blood pressure, and they've explored technology and text-based interventions as a way to help close that gap and provide more education. Likewise, there was telehealth service that presented earlier today, Maven Clinic, that was able to conduct a national survey of patients, pregnant patients, especially timely right now, about their attitudes toward COVID vaccines. And what they found was that a lot of the reticence to receive the vaccine was due to just misinformation. And there's really an opportunity for telehealth, if you include that to mean text-based support, to really kind of correct that misinformation. So I think there's gonna be a lot of benefits like that, that are more externalities of connected health. The second part of that question, the policy implications, this is huge.

You know, this is where the promise part really comes in. So one of the roles that I get to serve with ACOG is sitting on the MATCH group, and MATCH is the Maternal Applications of Technology for Community Health. A lot of the focus there is on legislative efforts to improve access to these telehealth interventions. There are some specific bills that are, I think, worth mentioning. So, for example, the Connect for Health Act is an act that would work on Medicare to enhance the availability of a lot of these services, from an infrastructure standpoint.

There's the Connected MOM Act, where M-O-M are all capitalized. This would be Medicaid patients and provide a lot of funding for the nuts and bolts of the wearable devices, the biophysical markers, and say, things like blood pressure cuffs, glucometers. Actually a lot of the work on this, the pilot work's been done in Louisiana. So those laws are worth knowing, but I think even maybe more approachable than that are certain topics. So a lot of emphasis is put on broadband access, and I think that's important, there are a lot of reasons we should be looking at that.

But in the meantime, we should still have ways to provide the same services for patients who have phone-only access. And so that is one thing that ACOG has fully supported. It was one of the waivers that was initially granted during the pandemic emergency response. It is now state-by-state as to how much of that waiver's been rescinded. But the idea is that we would advocate for patients to be seen or not seen, but to be getting a visit via audio only, and it would be organized and coded with an E&M code, the same way an audio visual is coded.

Similar themes have applied to the E&M coding for patient education, how to use these devices, 'cause some of them are new technology and the patients have be educated. That can be built into things that offices can build into their daily structure, which is easier when it gets reimbursed. So ACOG is in support of all these things. And I think there's gonna be a lot of interest in these new legislation efforts in the next year. Thank you so much, Nate. All right, and last, but not least, Monica.

What about the consumer community's perspective on these technologies and advances? How can they be included, participate in the evolution of big data? You know me, Joia-- I do, that's why I'm here for this. I'm here for this answer. You know I'm gonna say it all, 'cause I don't give a damn. For the people on the call don't know me, I'm a laboratory-based trained scientist. So let's be clear, I've lived in the Bay Area since 1993. I am not anti-tech, in fact I use it.

That said, I want us to really start to think more deeply about sort of the Plus-Delta of what we're trying to do. So I have been doing a process, that's been alluded to, called research prioritization of affected communities, and, basically, it is a way to be able to get community members to be able to generate, rank, and prioritize research questions that are important to them, that is contextualized by their experience. Prior to the pandemic, we did these in person. They were two hours. We had food and childcare and transportation. We remunerated people for their time.

And then there was six weeks in between and we had a second session, so that we broke them up. Well, we've totally done this virtually. During the pandemic, we've also created and maintained a 22-person national community advisory council made up of 14 states in three different time zones with the specific emphasis on, rural and Southern and black and Latinx communities.

And I will tell a couple of things. When we talk about technology, I can't believe that this hasn't come up, but we've sent swag, flyers, and packets in the mail, U.S. Postal Service as a technology during the pandemic has been crucial for us to stay connected with community-based organizations. So for people who talk about broadband and telephone and this, don't forget we have technologies of the 20th century that also can be leveraged appropriately to assist us. The second thing I'll bring up is social media. Right now we're about to disseminate all of our work on Instagram Live, on the community-based organization homepages of trusted regional and local folks, because we have those partnerships.

And so this idea, like I saw that Maven survey come out and I sat there and thought to myself, "Here's one of the limitations of big data. And here's one of the limitations of survey data." When we talk about misinformation, part of the problem is community-based organizations don't know who reputable organizations are, whether it's mistrust of healthcare organizations and institut

2022-02-17 18:44