Teaching an Accessible Online Course

TERRILL THOMPSON: So we are now recording. Over to you, Sheryl. SHERYL BURGSTAHLER: Welcome. Thanks for joining us. My team is always really happy to talk about this particular topic. So you're in the right place.

So I'm going to talk about teaching an accessible online course. And my name is Sheryl Burgstahler. My email address is sherylb@uw.edu. And this presentation is designed particularly for faculty members that don't have an extensive background in IT accessibility or for people that are working with faculty to help them make their courses accessible.

Particularly the pandemic, I've found that we need to keep the story kind of short and show them some simple ways that they can make products accessible. And then you can fill in the gaps with more technical expertise from our website or future webinars on document accessibility, or web accessibility, video accessibility, and so forth. The Accessible Technology Services includes two units. The IT Accessibility Team, Terrill manages that group. That started back in 1984.

It was just merged with other things that I was doing in my group. Very small, and then it grew into its own unit. And all of the IT Accessibility Team efforts are funded by the University of Washington. And so our goal is to make sure that IT procured, developed, and used, is accessible to our students, our faculty, our staff, and campus visitors. But we have another center as part of ATS which is called the DO-IT Center, where DO-IT stands for Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology. And this project or program started in 1992, supported with federal, state, corporate, and private funds.

So those grant-funded projects allow us to do a lot more than we can do just with University funds, and stretch out a little bit on our activities beyond the UW borders. We even have a program, a DO-IT Center in Japan, at the University of Tokyo. And that started in 2007. And there's some other implementations, particularly in Asia.

And then we also support the Center on Universal Design in Education, which started in 1999, with funding by the US Department of Education. So I'll give you an overview of kind of how we approach things at the university but also in our DO-IT efforts. We have a student-centered approach in what we do. And our model is about working with stakeholders like you that contribute to the success of students with disabilities.

And so we are have, as the hub, success of people with disabilities in higher-education and careers. In the case of the ITAT team, it's specifically related to technology. But DO-IT is more broadly focused. We take a look at who needs to be involved in order to level the playing field for people with disabilities, in this case a university campus or program, online learning, et cetera.

So certainly the person with the disability is involved. So we work with people with disabilities, their family members and allies, peers, near-peers, community groups, special programs, service providers like the Disability Services Office to provide accommodations, K-12 teachers and counselors, post-secondary administrators, faculty, and staff, employers of course have to be involved, technology vendors, funding sources, and federal agencies, and so forth. And so all of our projects in DO-IT are working with one or more of these stakeholder groups, all contributing to the success of people with disabilities. Our two basic approaches when we're working with students with disabilities, we're helping them develop self-determination skills and knowledge so that they can be successful in this not-perfectly-accessible world we're all living in. So that's our focus there.

And then, when we work with faculty or institutions, then we're talking about universal design. And I'm going to mention that as our framework when we look at online learning and other aspects of the university experience. So start with what we mean by having an inclusive course. It means that everybody who meets the requirements, with or without accommodations, is encouraged to participate. That means when courses are publicized even, and they indicate how you can request accommodation, things like that, everyone feels welcome. One of the most unwelcoming things that students are experiencing in many online courses around the country is a syllabus in a PDF format that is not accessible to them.

I'd say that's a very unwelcoming way to start the first day with your students and to treat that as an accommodation. And the third thing, that everyone is fully engaged in accessible and inclusive environments and activities. We could do all those things. And we kind of met our goal to make things inclusive. I'm going to give a really quick overview of the history and legal basis for accessibility related to online instruction, talk about accommodations and talk about universal design, some principles and examples and then resources. And then we'll have, hopefully, a little time for Q&A.

So here's the one-minute history lesson of the evolution of responses to human differences, including disabilities. And in some cultures still today, but mostly many years ago, people with disabilities were eliminated or excluded or segregated in some way. So they weren't part of the mainstream population. The middle of the last century, there was a movement more toward working with the person with a disability to either cure them of their disability or rehabilitate them in some way or provide an accommodation in an environment. Notice that all three things are focused on the individual with a disability. But now, more current thinking, which is a social-justice model or civil-rights model, then it doesn't make sense to only work with a student with a disability.

If they have a right to be in our classes, why aren't we making them more accessible to them when they show up? Why should we be surprised by that? And so then the response to social justice, like with other civil rights movements, isn't full inclusion. And universal design is just a practice or an approach that helps us get to full inclusion for individuals with disabilities. The legal basis, that's also very short here.

We could talk quite a bit about this, but we won't. Some people will say, well, why aren't any laws about making courses accessible? Well, there are. There are two primary federal laws that require accessibility. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and its 2008 amendments. You might think, well, those laws, 1973, there was no internet, no online learning to speak of.

And, well, the thing about these laws, they don't talk about specific access. They're civil-rights laws. And so they basically say that whatever we're offering at a post-secondary institution, we need to offer it to qualified students with disabilities and make employment accessible to people with disabilities as well.

So those are the two federal laws. But many states like our own have policies. We have policy 188 on IT accessibility.

But they mostly reiterate these two laws, maybe within some specific guidelines on meeting the requirements. So I'm assuming that most people in this group are not directors of Disability Services or people that work specifically with individuals with disabilities. And if that's the case-- most faculty members fit into that description-- it's probably best to just think of ability on a continuum. We don't need to know the difference between multiple sclerosis or muscular dystrophy, all these different conditions. But we need to think about people that are in our class might have a wide variety of capabilities. And so if we go from an arrow on the left, to not able, all the way up to able, everyone would fit on the line somewhere regarding their ability to do things.

And so the ability to understand English or social norms-- for instance, some are very able with that, and some not so much. It could be because of a disability that relates to their social skills. It could be because they were born in a different culture. It's not related to disability at all.

And that's kind of the point here, is it doesn't matter why people have different abilities. They just do as a normal part of the human condition. And if you go down the list, the same is true of the ability to see or to hear or walk, the ability to read print, write with a pen or a pencil, to communicate verbally, to tune out distraction, to learn and manage physical and mental health. And you might think of some disability categories that would be associated with some of these things, like the ability to tune out distraction and attention deficits.

But it's more important to just think about you have a wide variety of abilities in any class you're teaching. Another couple of things to think about when you're designing your course is most disabilities are invisible. And many faculty feel, if they don't see anybody in their class-- this would be in person but also online-- if it doesn't look like they have a disability, then they don't. And most disabilities are invisible, like learning disabilities, attention deficits, autism spectrum, and so forth.

And fewer than one third of students with disabilities report them to the Disability Services office. So even if you don't get a letter from a certain student saying that you need to provide accommodations, you may have a student with a disability that chooses not to disclose to that office. Because they think maybe they don't need an accommodation. And maybe they don't, but maybe they could benefit from them. And they're not disclosing because they're worried that they'll be discriminated against. They've had bad experiences with faculty members or teachers in K-12 that they didn't fully include them in things because they had a disability.

So there are various reasons why someone would choose not to register. And it could be simply they know they don't need an accommodation. A student might be missing one arm, but they can't see how they need an accommodation. Nobody is required to register with that office unless they need an accommodation. So you might not hear about them or be aware of them.

Disability Services is primarily offered accommodations to individuals-- and this is after and inaccessibility issue is discovered. So it's after the fact, in other words, not proactive. And when we look at our campus and many campuses across the country, and if we look at IT, which we're focused on today, is there are two things that are quite expensive in terms of staff time and even paying for outside services as far as accessibility. And so they spent a lot of time on making their inaccessible documents accessible, like the PDF issue I was mentioning earlier.

And that's mainly reformatting PDF files. And then the second one is captioning videos. And we like to remind people that, even if they put their videos up on YouTube or use some other platform, that there are editing features that they could use to edit those computer-generated captions before they use it in their class. Because computer-generated captions are likely not accurate enough to be an appropriate accommodation for a student who's deaf, for example. You need to get the punctuation in there, and spelling right, and so forth. Plus, if you're teaching chemistry or something, you probably have some words in there that the computer didn't figure out quite right.

So those are accommodations, including extra time tests and other things, that a specific student needs. And you'll find out about that on a letter from the Disability Services office. But sometimes it's the design of the product or environment that should be reconsidered. And that's what we're talking about today. How can we design the course proactively so it's more accessible to students with disabilities? And I have a coffee pot on the screen.

It's called the Coffeepot for Masochists. I've always been fond of this image. It's out of the Catalog of Unfindable Objects, which is out of print, but you can find it in used bookstores. Anyway, it has a spout and handle on the same side. And I think, if we took this product-- it was a nice design, it's quite attractive, I think-- and gave it to people to serve coffee at a reception, I think you'd get some pushback on that. They'd say, well, why are you making it so hard for me to use it? You might be creative and think, well, you could take the lid off and pour the coffee at the side.

Or if you happened to be an engineer of some sort, you might put some plastic tubing in and have maybe even a motor to kind of pump things up. Well, that'd be ridiculous. Well, that's what we're doing sometimes with students with disabilities in our courses. We're erecting barriers because we didn't think enough about making them designed in a way that is easy to use for those students with disabilities, or some types of disabilities at least. So we're trying to avoid that by having proactive design.

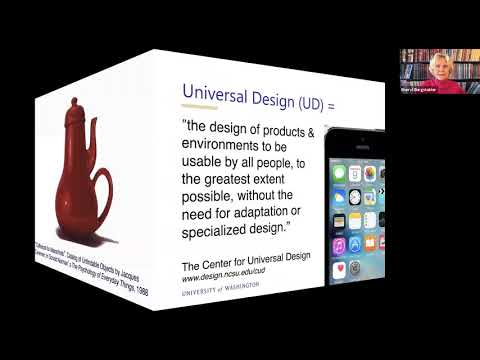

And so that's where universal design comes in. Universal design has been defined as the design of products and environments to be usable by all people to the greatest extent possible without the need for adaptation or specialized design. It's a very general definition.

The Center on Universal Design actually created it. And it basically says that we'll just-- when we're creating anything that's a physical space, or a teaching opportunity, or student service, or IT, or whatever you're designing that you think of the broad range of people that might be taking your class or participating in another environment and thinking about them when you do the design, and do your best at making things more accessible to those people that you're thinking of. So characteristics of universal design are that it's accessible. So technically it should be accessible to people with disabilities.

And we'll talk a little more about accessibility. And it's usable, which has to do with how you can perform functions in that software, so not just looking at some guidelines to make things accessible, but looking at what are the most important things that person does. And sometimes, with a software package, it's the first step in choosing what part of the software package you'd like to use that is a barrier. And so it doesn't matter how accessible the other things are down the road. And then it's also inclusive. So we tend to have products, for the most part, whenever possible, that can be used by people with a wide variety of disabilities and other characteristics, rather than create separate products for them.

So when we need separate products for people with disabilities, it's often in the form of assistive technology and add-on to existing technology. So I really like this quote here from a Vietnamese Buddhist monk. Because I think he was thinking of universal design and teaching. So "when you plant lettuce, if it does not grow well, you don't blame the lettuce. You look for reasons it's not doing well. It may need fertilizer or more water or less sun" and so forth.

And so when you're designing a course, and then you have a student in your course that's facing some challenges, rather than immediately think, oh, they're not trying hard enough, they're not doing things a certain way, they don't have the technical skills that they need and so forth, at least pause and ask yourself if you might have designed the course a little differently so that it would work for that student without lowering the standards of the course. So the more we build in universal design, then the fewer accommodations students should need. And I actually teach some online courses.

And that's definitely the same. It's kind of rare to have a need for accommodations. And I've had students in my classes that who are blind, are deaf, have all sorts of mobility impairments, disabilities, attention deficits, and so forth. And so we can reduce the number of accommodations. So that the image on the left shows a large circle with accommodations in it as a part of universal design. Because I consider the accommodations as part of the design.

But on the right, if you're really employing universal design to the max, then that the number of things in accommodations category will diminish a great deal. So that's what we're shooting for. You won't eliminate them totally, but you can get them down to fewer. So one perfect example of a universal design feature that has been fully embraced by our society and many others is curb cuts. This is an image on our front page of our newspaper here at the University of Washington, our student newspaper, called The Daily. And it's a man in a wheelchair.

It says "ramp the curbs." Get me off the street. And so there weren't ramped curbs back there in 1970.

And this person was just having to go up and down the streets. And I'm sure there were many people at our university that thought, this is never going to happen with all the hills at the University of Washington and Seattle in general. Well, it has happened. It has been embraced. And when you create a new sidewalk, it's not that difficult to put a curb cut in it. But going back and retrofitting all those old sidewalks was quite a chore.

And so we're kind of hoping something will happen, a paradigm shift, within other applications. And to kind of make the point between ADA compliance, as this people call it sometimes, and universal design, let's look at an entrance to a building here at the University of Washington, where you have a two-step entrance to the main door. And then you have a ramp to the left.

It looks pretty shallow and has handrails and probably is ADA compliant. But it's not fully universally designed because people enter the building in different ways. On the right, there's an image that shows a similar entrance to a building at the University of Washington. Except in this case, the primary entrance is really wide. And it's a ramp, but also, again, very shallow.

And so if you were walking side by side with a person using a wheelchair or a walker, in image number one, you'd part ways to get in the building, where in image number two, you'd go in together. And there are stairs in this particular building. And so if you want to use stairs, you can. But the idea is that the primary entrance is the one that's most inclusive.

It's most accessible to everybody and doesn't segregate people. The basic idea with IT is to build in accessibility features and then ensure the compatibility with assistive technology somebody might be using. So we minimize the assistive technology and the need for it by building in things like changing the color of your characters next to the background, having speech outputs and other things to make things more accessible. We just need to look no further than our smartphones to see about these accessibility features that used to be just things that they had in assistive technology for people with disabilities. And another point is, if you design something to be universally designed, including IT, it usually benefits other people as well. And so if we just take a look at a simple one in captioning videos, often we think of that for students who are deaf.

And so if you're unable to hear the audio, then yes, you need captions. But many other people benefit. Those who are English-language learners, those in a noisy environment like the airport, or a noiseless one like the library, or a bedroom with a baby sleeping, and those who might have a slow internet connection. and so want to turn off the video, and those who need to find content quickly so they can search for those content.

It makes it possible to search the content of the captions. So I think it's important for faculty then to basically consider the characteristics of students who might be in their courses and then the assistive technologies they might be using. Sometimes faculty will say to me, well, I'm going to create a survey. And I'm going to survey them on the first day of class and see what their needs are. That's not the process for universal design.

The first step in universal design is just to imagine you're going to have a broad range of characteristics. And then I'm not saying you shouldn't survey the students. But that isn't the most important part.

You should be prepared for a student with any type of disability. And it's probably not going to be 100%. But you can get a lot farther than if you haven't thought about it at all. What I do when I'm designing an online class is I think about some of the students that I know. And in the DO-IT program, we have a lot of students with disabilities and at the University as well.

And so that's easy to do. I know these four people. But if you even thought of these four people, and you designed your course accessible to them, then it's going to be accessible to a lot of students with disabilities.

Maybe not every one, but it will take you a long way toward a fully accessible class and inclusive class as well. And so the images I have here, Anthony, who doesn't have full use of his hands and doesn't have a usable voice. So he uses technology that he can have an onscreen keyboard and press the keys with his hand. But also he has speech output so that he can connect his device to a phone. He actually does phone support for a company that sells assistive technology. So he can provide phone support even though he doesn't have a usable voice himself.

And so that's pretty dramatic how technology has improved his life. And Jesse has multiple learning disabilities. And so she uses dictation software. Because she has a hard time getting her thoughts down on paper even using the keyboard. But she also has a reading disability. And so it's difficult for her to read her email and so forth.

And so she uses speech output as well, text-to-speech software. So it reads the content to her. So keep in mind, then, the computer's reading the content to her and then it's taken down a dictation. So she does quite well with that combination.

And there's Adrian. He's deaf. And of course he needs captions or other text or images to be presented if there's anything audio.

And then there's Nicole who has a computer science degree now. And she's totally blind. She does programming. And for her, she needs speech output. There's software available.

She can convert text to Braille and print out on her Braille embosser and so forth. So kind of think about those a little bit. And as you go down your journey, you might want to learn more about the technology they use. But that's just the introduction.

One piece of good news is, even though there are literally thousands of assistive technologies that people might be using, you don't need to know the details about that. Unless you're going to make a career of supporting assistive technology for people with disabilities, it's more important for you to have some basics about what the limitations are of that technology that somebody might be using. So this is just a simple, high-level, just a couple examples. And so looking at the assistive technology on the left-hand side of the screen and what that means in design of IT is up here.

So this assistive technology may emulate the keyboard but not the mouse. So someone with a mobility impairment like Anthony, the technologies that he's using, you can pretty much guarantee, will emulate all the functions that are on his keyboard, but not necessarily a mouse. And so what that means for web designers and software designers is that they need to make the products operate with the keyboard alone. And so things like-- just think of something you might use your mouse for to go and make a selection somewhere on the screen.

So perhaps a person can use the arrow keys to get to that spot. So you need designers that will build in these types of features so they don't just block people with disabilities out. The screen readers cannot read the content presented in images. So we have features to provide alternative text.

And that screen reader will pick up that text and read it to the person if they are using a screen reader. And so this could be a student who's blind, for instance. I like to bring this up because, probably in your learning management system-- here, we use Canvas-- it will prompt you for alternative text. But you or faculty you work with may not understand why. And that's why. So that would be an example too.

Some faculty might think, well, if I have a student who's blind in my class, then I'll go back and change all that. Well, it's much easier just to do it and you're putting images up on your pages in your learning management system. Assistive technology and specifically screen readers can tab from link to link on a web page. You might wonder why that matters.

Well, if a person is using a screen reader, perhaps because they're blind, they would like to see an overview of the web page many times. Like those of us who have sight would just look and kind of scan the page and think, oh, no, I don't want to go with these resources. I'd better look somewhere else.

So if you make the text on links and the same for each one-- and it might look orderly for you-- and so all the links say, Click Here, Click Here, Click Here, that's exactly what the person on their screen reader is going to hear when they access that web page. And so what you are telling the student who is blind using the screen reader is, oh, you have to read this whole page. And then you can kind of figure out which words are clustered around that hyperlink. And so that really is time consuming.

So another feature of screen readers is that it can skip from heading to heading within the document itself, like the PDF document or the Word document or whatever. And why would you need that? Well, if you're a screen-reader user, you might need it because you want to know how the paper's organized. It might be a 25-page paper. And it might be good to read the headings.

And they should be hierarchical. So you'll see, heading 1, heading 2, heading 2, heading 3, heading 3, heading 2. And so you can see how the paper is organized. Otherwise, if you just take text and-- say you want to have a heading, you just select the text and make it bold, the screen reader isn't going to see that as a heading. And so that's really important too.

Another thing that isn't hard to do. It doesn't really even take more time to do it if you do it in a design process. And then we already talked about the technology not able to accurately describe audio.

So then it's important that you caption your video and transcribe audio. So it seems pretty simple. That's, like I said, really high level. And there are many technical people on my staff here that can give you a lot more detail. But that's kind of the overview. So I often get asked by people, well, do I have to learn all these various technologies and so forth? Well, it's fun.

It's really interesting technology. And you might want to use a screen reader. But you may not be able to be proficient enough to really tell if the website is accessible using that unless you invest some time in it. So you might think of, well, what are going to be the limitations that I can actually see? And whether your website can be used without a mouse-- just put your mouse aside and see if you get to everything. And then you'll have a simulation of what it's like for a person using a screen leader who happens to be blind.

There are a lot of universal design principles. And you can thank me very much, I'm not going to go through all of them. But to cover all aspects of higher education, I like to point to three sets. The definition of universal design, we already talked about. And the original people that created that definition also developed seven principles of universal design that can be applied to anything-- a physical environment, technology, teaching.

Anything that we're doing can use those principles as guidelines. But there are three that were added quite a bit later, by CAST, an organization. They came up with three Universal Design for Learning Principles. And they're particularly suited to the learning environment. So particularly with online learning they would be worth looking at. And then I also like to include the principles that underpin the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines.

There are four of them. Because sometimes what people will do, they'll only use one set. And they might be designing online learning.

And all they do is UDL, and not deal with accessibility. And as I mentioned earlier, I consider accessibility part of universal design. So learning all three sets can be a good way to start. However, we have short time today.

And you might be happy to know you don't really have to memorize all those. If you look at our website, which I'll give you the URL for, the Center for Universal Design in Education, you can find out what they are and see specific examples. But here's kind of a rule of thumb. In a nutshell, if you did these three things, your course is going to be pretty accessible and inclusive and usable.

So number one, provide multiple ways for participants to learn and to demonstrate what they have learned. So teaching a concept using short video, and then maybe having a handout or a website or something where they can also get that same content as a reinforcement. Or you can do one or the other if the content is basically the same. And then the second one is to provide multiple ways to engage.

This can be helpful in a course you're teaching online, you're preparing for students in your class by applying universal design. Communication systems are the way to engage. Some are more accessible than others.

So one thing I do on my syllabus is I always say you can meet one on one. Just make an appointment with me, send an email to such and such. And then I say, and we can meet with Zoom or the bulletin board system, part of the learning management system, email, or anything else you choose. And so the idea is I give them the choice. So I don't need to know whether Zoom is not very accessible to somebody in my class. They get to decide that.

And so and also I don't have to use a technology that some students might be uncomfortable with. There might be people who don't want to be on a Zoom call. It might be because they're English-language learners and they're a little embarrassed about their English skills and would be more comfortable to do an email so that they can do some spell-checking and so forth. And so giving students control, when possible, is a good way to apply universal design without learning a lot of details about how accessible one product is. So the second one is multiple ways to engage.

So that's that second one. If you take a look at the first and second one combined, those are just basically the three principles of Universal Design for Learning just stated a little differently. And then the third one is the one that gets into more of the general principles of universal design and the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines underpinned by universal design principles. And so what it says, besides those first things that was Universal Design for Learning, ensure all technologies, facilities, services, resources, strategies are accessible to individuals with a wide variety of disabilities.

So you ensure that accessibility beyond some of these universal design principles and the other two. So the rest of time, I'm just going to scan through some basic practices. I developed a checklist with 20 tips.

And the whole idea was I was hearing from so many faculty members I talked to that don't even know where to get started. And they also got the idea that everything is really hard. Because maybe the first thing they learn is how to redesign an inaccessible PDF. And it's like, I don't have to do all this stuff. And so I decided to create a checklist. And Terrill Thompson, on my staff, he had 30 tips on how to design accessible websites.

And I thought I'm going to beat him by having fewer on my list. Not really, but it's a good story. So this is available online. The URL is on the screen here. But you also, these days, I can search for 20 tips-- that's 20 as a number-- just with a Google search, and often this handout comes up number one or at least one of the first items because it's used by a lot of people.

And you can feel welcome to link to it as well. It's been developed and has been edited over many years. And so it's not a perfect list. And I can always think of more things to put on there. And I do adjustments as people give me additional ideas.

Nine tips are about the technology, essentially, how it's designed, how accessible it is. And then 11 for the instructional method. So that's more the pedagogy, like the Universal Design for Learning type things and good design practices. And the difference between that handout and what you see on the screen today is that there are links to resources for doing the things that I'm talking about.

Like where to get started to look at how to make a PDF document accessible, for instance. And so you need to look at the online document to get those places to go to if you want to learn more about any of these particular things. So they were developed with a literature review report to online instructors.

We have a lot of capacity-building institutes and other programs where we hear from people. What they're doing, what works, what doesn't. But also students. And one little side is students with disabilities, when we put them on a panel and have them talk about how accessible online learning is to them, the things that they bring up often are things that any student would say. And I'll point out a few things as I go through this list. There's not really high-level technical details.

And now, you have to have a certain level of access to even get that kind of feedback. But a lot of the stuff, as you'll see, is not rocket science. And so the message is that you can do some accessibility things and inclusive things without a broad background in IT accessibility. So when we're looking at web pages or documents or images, or videos, even, here are a few things. For layouts and organization, this is often presented as a problem for students with disabilities. Now, having worked a lot recently with faculty members that are throwing everything that they do in person online because of the pandemic, you can look at those courses and you'll see a great deal of inconsistency in the layouts and organization schemes.

And I have a lot of forgiveness for these faculty members, by the way. So maybe the first iteration, that's OK. But then they should just go back and see if they can decide what their format is going to be, and be consistent with it throughout the course.

That could be very helpful for students with some types of disabilities and sometimes when it affects executive functioning and so forth. And it would benefit other students as well, I think we would all agree. Use text format. Don't put it in a scanned-in PDF-- that's just an image-- because it can't be read directly by a screen reader. And then, with that text, also structure the headings-- I already talked about that-- using the heading structure that is in the package you're using.

It could be a learning management system, or Word, or other package. You can look and see what the accessibility features, and see if there's something like that. And lists as well-- I think most people use the style function within Word to create their lists. But I still wanted to document so, if that's not the case, and they just manually put in a dot in front of the items, then what happens, if someone reads it with a screen reader, it doesn't distinguish those items as lists. And so it just may come across as just a flow of ideas. And a list structure, as we know if we do have sight, it benefits us.

It helps us organize our thoughts. And so that's why you need to do that as well. And the third is descriptive wording for hyperlinks, also for screen reader users. Guidelines in doing that-- I like to keep it really short and specific.

Doesn't have to be a really long one. And there are actually guidelines. You can search around the internet, you can find some guidelines for that as well. I've already said I would avoid using PDFs unless you want to invest some time-- that's OK. Some people, they insist on having a PDF.

We're working with a center now, for the last couple of years, and it was in an inaccessible PDF. He didn't really want to learn how to make it accessible. He just wanted to use it that way. So they sent these out using email, and then put them on their website. And so his solution was just to have an accessible Word document, but also have the PDF. And that's maybe not the best solution, but it's a good one.

If you look at the DO-IT website, we have a lot of handouts that people can usually print and pass out in their own sessions, not so much now. But I liked that PDF for that, because it looks good when it's printed. But then we have an HTML version, which is easier to make accessible. And it's more accessible in the grand scale. And so we have an HTML copy as well. We just have two versions.

But the thing that's unique about our program-- maybe not totally unique, but there aren't a lot of programs that do it that I run into anyway, is the one that's the default version is the HTML version. And so you have to click on the PDF link to get a PDF copy. Most of the websites I see, they do it the other way around, and say, well, here's this nice, beautiful PDF.

If you want an accessible form, click here. So I really encourage people to have the most accessible thing that they have featured, kind of like that ramp going into that building that I mentioned. So that's critically important with the primary content. But all content is good. Some people will say, well, what about all these things I'm linking to? They're PDFs.

And they look a little closer, and realize that they're images, because they can kind of try to select the text and it's just one big image. And what I tell them if they're just getting started is, well, first of all, searching around the internet, you might be able to find an accessible version or your librarian might help you do that. And so that's a good thing to do. But you also might have to just wait.

And that will be considered an accommodation. But you're at least aware of it. And at least not adding more inaccessible PDFs to the world. And include text descriptions of content and images.

I already talked about that. That's another one you can find some good guidelines out on the internet. And there's a link to one or two in that document itself, the 20 tips. And there are also really specific guidelines on particularly large, complicated graphs, like in science areas and so forth, and large, complicated tables. One particular guideline is to just keep those images and the table as simple as you can in structure. And so you might divide that table into several parts and make it more linearized so there aren't so many subareas and subareas and subareas.

So those complicated images do take some work. The simpler ones, I like to tell people just use your own common sense. Because you know the content yourself.

And just make it descriptive. And you don't have to tell about everything. You might have noticed that, when the red coffee pot was on the screen, I just kind of slipped in that the handle and the spout were on the same side. The reason I did that is I'm not assuming that everyone can see the screen. It could be because of a disability. It might be that you don't want to have the screen on because you have slow internet connection.

Who knows. Who knows but I just assume that there might be people watching this that are not accessing the image. One way to think about that is imagine somebody's calling in. So how are you going to describe that without a really great deal of detail so they understand the point you're trying to make? And so the coffee pot, even though I really like the red color and other qualities of it, I didn't bother to describe all that. But I did give the distinguishing characteristics that make it an interesting example.

So web pages, documents, images, and videos, page 2 of 2. Large, bold, sans-serif fonts, uncluttered pages, plain backgrounds. I'm demonstrating that today. You might make exceptions on that. But for people with visual impairments and some learning disabilities, it can be very difficult to read if there's a busy background.

So maybe make your PowerPoint not quite as pretty as you'd like to benefit many people. Use high-contrast color combinations. And avoid problematic ones for those who are colorblind. That's something you could easily explore. And there's a link on the 20 Tips handout. I'm told that green and red are particularly difficult for many people with colorblindness.

But my practice is to always make sure that seeing the color is just an option. And so you might have a couple of buttons on the screen. And you might want people to choose one. And they're all triangular in shape, then you say, choose a red one for this one and a blue one for that. Then a person who's colorblind may not be able to follow what you want them to do.

But if you made each one a different shape and a different color, then you can say, choose the blue triangle or the red circle. And then, again, you don't have to know whether it's a problem for anybody. You've just anticipated that it might be sometimes. Make sure videos are captioned. And audio description is good too. That's not done as often.

But it gives you a little extra audio where the reader reads something aloud, like maybe the title of your video or the credits at the end. I encourage people creating their own videos to try to speak all the content so a person-- a student, for instance-- can get all the content by listening to what you're saying and including the credits at the end, the acknowledgment. You might have something like, on our videos, it says, "for more information on this topic, consult--" well, just speak that. And so if you don't have the extra audio description in there, at least a student would be able to hear that. And as much as we all love to have all kinds of technology tools, the greatest this and that, I recommend that you avoid using a large number of them.

And stick to the learning management system tools. For one thing, the students will get used to those tools and be better at using them. And then also, when you're using things away from the LMS, make sure that they're accessible.

Like for instance, can you use them without the keyboard alone? And that might take some consulting to do that. But it's good to check. There are actually some lists out on the internet where you can just post a message to the discussion list and say, hey, have you checked the accessibility of whatever you're thinking about using. ATHEN, A-T-H-E-N, all caps, is an organization that has a discussion list. And it's highly-technical people regarding accessibility. And so you often see messages out there where people ask that question.

Address a wide range of tech skills and point to resources. When I teach online, I assume that there might be some of my class who' never used Blackboard or Canvas or whatever I'm teaching the course in. And so I know there are a lot of user documents that can help them do that. But I also know there are tons of documents and videos.

And so what I do is say, at the beginning of the course, if you haven't used this learning management system, I suggest that you start with these three resources and point them to them. Because you alone know which ones are going to be needed, especially the first couple of weeks of the class. And then make sure that the content is presented in different ways. We talked about that, as to UDL. Multiple ways to communicate and collaborate, another UDL principle. And multiple ways to demonstrate your learning.

So giving students choices or, if not choices, at least different ways-- so all of your tests are not exactly the same format and so forth. So some students that aren't so good at one way to show they've learned something might be better at others. Be sure to address a range of language skills. Just using plain English. One of the biggest complaints I get from students with disabilities, but I think with the other students as well, is faculty members that don't spell out or define acronyms and jargon. Even jargon that you might consider that everybody knows, like I use the expression, "low-hanging fruit" a lot, particularly when it comes to accessible design.

And the first time I use it in the class where I might be teaching, I always define it. And I just build it in. I just say, if you haven't heard that expression before, what I mean by low-hanging fruit is whatever.

Make sure the instructions and expectations are clear. I like to put all my instructions on assignments in great detail in the syllabus. Because then you're allowing the student to plan their time.

So if they're going to need extra time on something, they can do it early on rather than later. They can get started right on day one in some of those things. Make sure assignments are relevant to a diverse audience. Think up some clever different ways of saying things. Providing outlines or notes or other scaffolding tools so that students maybe that are a little weak on study skills might be able to learn something from you in the early days of the class.

And I like the word, scaffolding, because that implies then the scaffolding is going to come down. So it's just a crutch to get started. Make sure there are adequate opportunities to practice.

In some cases-- I used to teach mathematics, but not online, actually. But some students just need a lot more practice. And so you can easily build in extra practice by giving the assignment to the whole class and then saying, if you feel that you need extra practice with this, here's another. And you make that an optional activity. And you might think, well, students aren't going to make that choice. Some will.

And that gives them an opportunity to own that they're going to learn that concept. And we have one more. Feedback on parts of an assignment and corrective opportunities. If a big project, if you can give feedback, like first have a student say what they're thinking about doing for their project. Maybe even check in midstream to see how they're doing and give them further feedback.

So now I have other things I wanted to mention. And I'm not going to go above 20, because I'm going to lose the competition to Terrill. But one thing I like to mention is using accessibility checkers in Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, in the learning management system, and other products you might be using. Along with the accessibility checkers, often there are templates like PowerPoint.

And the advantage of using an existing template-- and maybe modifying it somewhat-- is that those templates tend to be designed in an accessible way. And they will be pointing you toward accessible practices rather than just creating a lot of text box boxes in create-your-own design. And then, when you're choosing IT tools, get some help from a consultant on whether they're accessible. But you can do a few short things, like checking for the Accessibility page on the website of the product.

If they don't have an accessibility page, there's a real strong possibility they haven't thought about accessibility at all. Otherwise they'd put their page and brag about it. And there's the Voluntary Product Accessibility Template used by the federal government. And software and hardware vendors need to fill it out in order to style to the federal government.

You can look that up and see what they say. Keep in mind it might be their marketing people that created a VPAT and also the Accessibility page on their website. So it's not a perfect thing.

And then the question on the ATHEN discussion list I mentioned. And there are some others as well. And see if you can operate the technology with the keyboard alone.

So there's just a few ways to get started. So anyway, we're kind of close to the end here. On our DO-IT website-- I mentioned DO-IT early on-- we actually have an extensive knowledge base. Because there are some specific things that you might find-- you're not going to find in these guidelines for getting started or even on more comprehensive websites, but for example, STEM content, I haven't really talked about that. Everything applies to STEM content.

But we know there a lot of symbols and things that make may make it more difficult. And so in our knowledge base, we have a lot of Q&As. And so there are just a couple of them. Are there guidelines for creating accessible math? Yes. And how can I create math and science documents that are accessible to students with visual impairments? How do I create online math content that is accessible to students who are blind? And what are some techniques for creating Braille math materials? And so you can really get into the technical details once you make the basic considerations that I'm talking about today. So this is just the beginning.

But if you're training faculty, I would encourage you to use the 20 Tips, but also to edit them for yourself. I mean, you want to exchange some of the ideas with some others that you would choose for your group. And you'll notice, at the end of that handout, that it says you have permission to even edit the document as long as you give credit to the source, which is DO-IT in that case. So if we look at universal design, it values diversity, equity, and inclusion. So it can be used for part of the framework for your DEI efforts, those initiatives on all of our campuses these days, to make things more inclusive of multiple groups.

It promotes best practices, does not lower standards, it's proactive and can be implemented incrementally, benefits everybody, and minimizes the need for accommodations. So that's kind of the summary. And the real super-short summary is this is all just good teaching. I was a middle-school and high-school teacher early on, taught math, later some computer science. But a lot of these things, some of these practices you learn in teaching and development classes. But not all of our faculty have had those classes.

But these are just simply good practices in teaching. I think of captioning that way. It's a good teaching practice. But it also is a necessary accommodation in some cases. So resources-- I mentioned my email address in the beginning. But I have that up here as well, sherylb@uw.edu.

That's Sheryl with an S. The Center for Universal Design in Education at uw.edu/doit/cude. But you can just search for the Center on Universal Design in Education and you'll find it. Accessible DL, that's another one-- AccessDL, actually, all one word. That's a website on, specifically-- with the 20 tips, but also many more resources, not just our own, mainly other resources that you can use to go down your journey on accessible IT. And that's at uw.edu/doit/accessdl.

And so then there's Accessible Technology. That's the UW group That is managed by Terrill. And his team keeps this website up to date.

uw.edu/accessibility. And we're proud to say it's actually a link off the homepage of the University of Washington. So that's very cool. It's the bottom of the page.

Accessibility is the link. Oh, hot off the press, a new book that was created with a lot of input from the DO-IT projects we've have. Creating Inclusive Learning Opportunities in Higher Education-- A Universal Design Toolkit. And you can get a 20% discount with code INLEHE. Anyway, if you go to the Center on Universal Design in Education, you'll find that listed there.

So Gaby, do we have any questions? GABY: Yeah, we have a question that was posted in chat. Sarah asks, do you have advice for when there are conflicting access needs between students or between student and instructor? SHERYL BURGSTAHLER: Can you give me an example? GABY: Sarah, are you still-- it looks like she's still on the call. Do you have an example that you can share with us? AUDIENCE: Can you hear me? SHERYL BURGSTAHLER: Yep. AUDIENCE: Can you hear me? OK. OK, so like in my class, I can't really use a computer mouse or keyboard.

And I needed to caption videos for a student who doesn't hear. And I needed to do it myself. So there was a clear access conflict there. And it was a situation which I had to do something within 24 hours. So there wasn't an option for getting help. SHERYL BURGSTAHLER: Yeah, well, if you did the captioning before the course started-- or are they videos being created as the course is going? AUDIENCE: So actually this is a bigger structural issue in that situation, where I wasn't told until like three days before the course that there was a student who needed this accommodation.

So it's a bigger structural issue. But I'm thinking more so when you have the issue of, like, if you had a blind student and a deaf student, you could have a conflict in the way you're delivering content and the way you're choosing to do things to be more visual versus more auditory. TERRILL THOMPSON: Yeah. Often, I think that first example might be requesting an accommodation. It seems like a reasonable accommodation for you at your institution.

That didn't help you at the moment, I know. But often, if you apply universal design-- it's one reason I like that model-- is because if you follow the practices, you don't run into conflicts as much. And then sometimes you have to compromise. I think of an onsite example, when a student is using a sign language interpreter and another student has attention deficit. That can be really disruptive to the student who has an attention deficit.

And I would do the same thing online. But I would work it out between the two people-- or myself, in that case-- and see how we can make it happen. So providing options often helps. I have an assignment in a class I'm teaching on universal design where I have people go out to the internet, find an image of a physical space that appears to have a universal design feature that's not labeled as such and attach it to a message in the discussion board.

And then explain to the group why you consider that to be a universal design feature. But right into the assignment, I say, alternatively, you can describe a physical space you have had experience in where some feature of that physical space you would count as universal design. Then explain that to the group. But also the people that use images, then, they have to describe those images so a person can respond who might be blind. Anyway, the assignment, you think of a very visual thing and it would be hard to make it accessible. It's not really that hard if you give people options.

Now, I've had quite a number of people use the "describe a physical environment you've been in." And to my knowledge, they're not gone. And so that's a plus, too, I think, with universal design. But anybody can do it. Just make an option. You can decide.

You don't have to tell anybody why. GABY: OK, that is all of the questions that we have in the chat. SHERYL BURGSTAHLER: So we're at the end of our time period, too.

I will stay on. And some people on my staff will stay for a little while here. And so if you have a question, maybe something was beyond the scope of this talk, we can keep chatting here.

But thanks for coming. And you can leave now if you want, or hang out with us for a few minutes.

2021-04-18 16:53