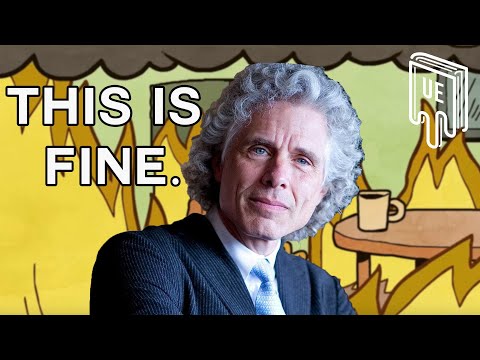

Steven Pinker and the Failure of New Optimism ft. We're in Hell

As a deadly pandemic continues to ravage the globe, it's natural to reassess the widespread notion that the world is getting better. New Optimism has emerged over the past decade or so spearheaded by Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker. Pinker's 2011 book 'The Better Angels of Our Nature' details how violence has declined over human history. Following its success he wrote 'Enlightenment Now' which extends the argument that things are getting better to a wider variety of measures including health, wealth, the environment, and human rights. As the name suggests the book

attributes this progress to ideas of humanism, science and reason which find their origins in the period of 17th and 18th century thought often referred to as The Enlightenmen. The book is a best seller and has received many plaudits, for example Bill Gates called it his "new favorite book of all time". Pinker even got a spot on Joe Rogan to promote the book "Yeah I'm- I'm an optimist and I, I really do look at all these trends You'll, you'll like the book then 75- beautiful 75 optimistic graphs Oh excellent! Yeah I think that if you look at just the overall human race, I mean one of the Hahaha yeah great man - I'm not gonna read your book A standout feature of New Optimism is its reliance on graphs and figures to prove that the world is getting better and this is epitomised by the website 'Our World in Data' run by Max Roser, which aims to document human progress using quantitative measures.

Another prominent New Optimist is the late Hans Rosling whose book Factfulness and associated Ted Talks used statistics to wow audiences with how wrong and pessimistic they were about the state of the world. Oh people can come up with statistics to prove anything Kent, forfty percent of all people know that. There are numerous ways to critique Pinker and the New Optimists as their claims are quite wide-ranging. Many have critiqued the data they use, especially those with respect

to violence, the environment, poverty, as well as the various social problems associated with modernity like loneliness, stress, and mental health. Others have largely accepted the data but critiqued the conclusions drawn from it, especially the attribution of progress to The Enlightenment and the implicit or explicit defense of the status quo. Others still have focused on Pinker's awkward dancing, which many claim single-handedly refutes his argument that the world is getting better.

In this video I want to critique Pinker's analysis of wealth, poverty, and inequality and present an alternative vision of how these things work and why they matter. These three issues are intertwined and as we'll see Pinker frequently discusses them together. I'm going to begin with absolute poverty, which pinker cares about but doesn't understand, then move on to distribution more broadly, including relative poverty - which pinker doesn't care about and doesn't understand. I will conclude with some policy recommendations that would ensure a more equal distribution of wealth across the globe, aiding both absolute and relative poverty. So...I hope you're ready for a nice

long, dry Unlearning Economics video. I mean we're really gonna get into the nitty gritty of the data I'm talking 100 page reports, big quotes, tables, no respite, no fun at all! Everything's fine Hmmm... that was weird. Steven Pinker's view of poverty is a common one: for most of humanity's history we found ourselves in poverty and it was only with the rise of Capitalism, or The West, or The Enlightenment or whatever you want to call it that we escaped this trap. You may be familiar

with this graph of GDP, used widely to illustrate our historically unprecedented levels of wealth. The hockey stick shape shows GDP as virtually stagnant, taking off exponentially in the 19th and especially 20th Centuries. As Pinker states: I wish this wasn't a real quote - for a lot of reasons. Look, I'm not qualified to engage in a debate over whether hunter-gatherer societies were 'better' than contemporary civilisation and nor would i want to argue that they are. But by looking further into the data we can see how crude Pinker's narrative really is. Pinker also relies heavily on another graph you may have seen showing that extreme poverty has declined precipitously in the past few decades. The graph is

based on the World Bank's line of $1.90s worth of consumption per day, under which people are thought to live in extreme poverty. It shows the proportion of people who are below this line over the past couple of hundred years. Those living below $1.90 were about 90% of the population at the beginning of the 19th century but are about 10% of the population today. In a response to critiques

of his book as overly obsessed with quantitative metrics, Pinker justifies his stance as humanistic: Such a view is extremely naive about quantitative data which, as we'll see, often excludes large numbers of people. The data from these two graphs warrant special skepticism because they summarise information across a wide range of contexts and over long periods of time. Data don't fall from nowhere; they have to be gathered and the process is often costly and biased. Well-established statistical institutions which credibly measure things like income, health, and literacy are largely a privilege of modern rich countries and in both poorer countries and in the past the information is just not available. At a deeper level, modern notions of GDP, income, and poverty

may not even be relevant in these times and places. It's not just that the data are missing, though - they are biased in a specific way which overstates the wealth and prosperity of market economies. I want to warn you that I'm about to dissect this data and it might sound quite pedantic and academic but there's a lot at stake with these numbers: understanding how billions of people are living and designing policies based on that understanding. Poverty measures are used explicitly

by the World Bank and across the globe, so it makes sense to subject them to this much scrutiny. The anthropologist Jason Hickel, who is known as a critic of the New Optimist narrative on global poverty, has critiqued the GDP data, which also turns out to be the basis for the poverty data before 1981. In other words the two graphs we've just seen use a common source, though after 1981 the poverty data is measured directly. For this reason I'm going to discuss the two periods separately: first, the historical GDP data and then post 1981. Hickel has highlighted that historical data on GDP simply isn't available for most poor countries: He adds that the data available for the past were mostly gathered by colonists and so reflected what they were interested in - in this case, grain production for export to the home countries. As such, the data exclude non-market forms of consumption which people used to meet their needs before capitalism: The fact that these statistics privilege market consumption over non-market consumption, even to the extent that measured output may increase while people are being forcibly dispossessed and facing starvation, should give us a clue that they are missing crucial aspects of poverty.

It's likely this data overstates the extent of poverty in pre-capitalist and pre-colonial societies and understates it in early capitalism and colonialism. Inequality researcher Branko Milanovic has agreed with Hickel on this point, though he added that it makes recent decades look better because the world has largely escaped the horrors of early industrialisation. However, if one is celebrating the triumph of progress and the West - as Pinker is - the gaping hole where poverty increased for a century or so raises some serious questions. One could probably say

something similar for other outcomes such as life expectancy and violence, though the improvements related to modern medicine like vaccines and infant mortality are likely to be more credible. More on that later. The economic historian Robert Allen has tried to improve on these estimates by looking at the consumption patterns of households in pre-industrial England and pre-colonial India: The canonical poverty and GDP graphs basically depict all of mankind as completely impoverished before capitalism It's only the miracle of consumer capitalism that means you're not lying in your own s***, dying at 43 with rotten teeth. But Allen's estimates suggest that this wasn't the case. People and systems before capitalism, whatever undeniable problems they had, were often able to provide at least enough to keep themselves out of absolute poverty.

I will readily admit that this is more in line with my own expectations and therefore probably my own biases. But as Allen's final sentence makes clear, we can't just bandy around estimates used by researchers as if they are settled science and certainly not to support wide-ranging historical narratives, or a political ideology. That's the way these graphs are used by Pinker, not to mention by Max Roser and Bill Gates on social media. Let me bring up the graph I don't want to look at a graph mate, I ain't got time for a bloody graph! This is what I wanna take - this opportunity to talk to the people of this country and tell them to get involved in creating direct action.

That's a lovely graph It goes back to 1862 This is the kind of stuff that people like you us to confuse people like us "oh I've got a graph mate" I'm not trying to confuse you You've not just come from the new era estate where Boris Johnson who takes five times more meetings a year with bankers than he does ordinary people - we've got a graph, everything's tidy! Let's move on to the data after 1981. These measures are actually designed to measure poverty rather than GDP. It's therefore not surprising that they appear more robust to different approaches and assumptions than the data before 1981 and I want you to keep that point in mind: the decline in global poverty since 1981 is a pretty credible finding. Of course, this doesn't absolve us of investigating the data. The economist Angus Deaton has called estimating global poverty "the statistical problem from hell" and has even stated that "global poverty and inequality measures are arguably of limited interest". One of the most fraught issues is adjusting for the fact that prices are different across different countries. Although

the line is expressed in dollars, this has to be translated into the currency of each country to make it comparable. Most things cost less in poorer countries so the rupee equivalent of $1.90 is less than if you just converted it a currency exchange. These price adjustments typically take a basket of goods supposed to represent average consumption. As they are usually created for our old enemy GDP they reflect total consumption in a country. This matters because the poor within a country spend a lot of their income on food and other basic needs. If you spend 50% of your money on food, a rise

in its price is going to have a big impact on your budget. But inflation is measured from total GDP which includes poor, middle, and high income people alike, so the percentage spent on food for the whole country will be lower than for those in poverty. A rise in the price of food can have a small impact on measured inflation but a big impact on the poor. It's therefore possible this leads to the measures understating poverty. Changes in the way this is all accounted for can

change the number of people in poverty by hundreds of millions, even though this statistical exercise obviously doesn't involve any changes in the lives of poor people. However the issue is mathematically detailed and I think is ultimately a bit of a distraction as the measures have genuinely improved over time, so I won't go into it any further. But check the references if you want to know more about poverty measures and price adjustments. Although the coverage of the data after 1981 is leaps and bounds better than the historical coverage, it's far from perfect. The World Bank aren't all powerful and can't just magically know everything about global poverty - even if they'd like to think so. Poverty researcher Morten Jerven summarises the problem as:

This is true not just of poverty indicators but of one's measuring progress in health and education too. Almost half the countries in the world bank's database either have no data on poverty or have it for only one year. It's difficult to speak about a reduction in poverty when you don't have a comparison point from the past and even more difficult when you don't have any data at all. Only a minority of countries can be said to credibly track poverty over time. Now, the countries without data are usually smaller, so when you weight for population fewer than half the world are unrepresented by the data. China and India have fairly good poverty data

and together they make up a third of the world's population. Additionally, the measurement problem has been improving over time, though it remains far from solved. Even in countries with data the poor may not be properly accounted for. It's natural to think of the global poor as a class concentrated

within the poorest countries in the world and this isn't completely wrong, but a substantial number of the world's poorest exist in relatively well-off countries with high inequality. Latin America is the archetypal example here, with its vast riches and slums side by side. As the average income level of countries like this rises the poor can be increasingly shut out and need more to get by than the poor in poorer countries. Needless to say, there is generally a racial dimension to this poverty. There are also poor people even within relatively well-off families. Since standard poverty measures use household income, it's possible to conclude that high household income means all members of a household are out of poverty, ignoring inequality within the household. Naturally, there is a gendered

dimension to this poverty. A paper by Brown et al found that most of the undernourished women and children in a large African data set were outside households we would think of as 'poor'. Even in richer households, the income was controlled by the household head, usually a man, who would take care of himself before everyone else. Philip Alston points to yet another class of people ignored by the World Bank's poverty narrative: I also have my suspicions that we might be facing the same problem we had with the earlier data: the underestimation of non-market consumption. If people were doing better than we thought before modern capitalism, then obviously the gains from transitioning to capitalism will be overstated.

Modern estimates are much better at accounting for this than the GDP ones used for historical data that we saw earlier, but in some cases the number of people recorded in extreme poverty by these measures defies credulity. The chairman of Kenya's National Bureau of Statistics once said that: Andrew Fisher has argued that the graph implies the overwhelming majority of Chinese people in the 1970s were only just getting 2,000 calories a day on average, when at the time they were farmers engaged in demanding manual labor and would have required at least half of that again. While China in the 1970s was austere, this would have meant widespread malnutrition and starvation, more in line with china a decade or so earlier during the Great Leap Forward. In summary, the canonical graphs that show wealth rising and poverty falling are not credible for understanding wealth or poverty for most of human history, as well as among contemporary countries and groups which have remained disconnected from the modern economy. It's hard to escape the conclusion that both the hockey stick and poverty reduction graphs represent not just a story of progress, but a qualitative transformation of the world into a capitalist economy. Both measures rise organically as human activity is brought into the market, even if people are not escaping poverty. None of this is to say that the graphs don't represent

any progress whatsoever; just that we need to be careful when interpreting them. This is especially true for societies that are the most transitional: richer countries in the past and poorer countries today. Iit also throws up questions about whether poverty is truly the natural state of man or if it is imposed by economic and social systems.

Everything is fine Bearing in mind that the dominant poverty measures tend to exclude those not well integrated into the global economy, how do they do it mapping poverty among those within the global economy? (Which, to be clear, is the majority of humanity) Poverty is commonly understood as a situation where people do not have the capacity to meet their basic needs: food, water, shelter, clothing, etc. It is therefore strange that the link between the World Bank's $1.90 a day poverty cut off and basic needs is not concrete and more explicit. The graphs depict extreme poverty as a cut off

for the money value of each person's consumption, currently set at $1.90 per day. The thinking goes that this permits enough consumption of the basics for people to survive, albeit at a bare minimum. Originally the $1.90 line was based on an average of national lines from a 'very small' sample of the poorest countries, though this was beautifully updated to only a 'small' sample of the poorest countries later on. These national lines used different methodologies and all were

questionable because of the lack of statistical capacity of the countries they came from. Jason Hickel argues that this line is just too low to be meaningful - for example, the number of people who are going hungry is higher than the number of people deemed in extreme poverty by this metric. Hickel has drawn from research by Peter Edward to formulate a new poverty line. Edward has noted that if you look at the relationship between life expectancy and consumption, there seems to be an inflection point before which higher consumption leads to rapid gains in health and after which higher consumption leads to only modest gains in health. We have here an individual's consumption on the x-axis and life expectancy on the y-axis.

Below the level of income shown by the kinkpoint, people are unable to satisfy their basic needs. At this level of impoverishment, a gain in consumption will rapidly increase their life expectancy, hence the steeper line on the left part of the graph. They will go from eating nothing or only carbohydrates to getting the nutrients they need, and from being exposed to the elements to having at least some protection. The point at which they meet these basic needs can be represented by the

kink and beyond this the gain in life expectancy from income vanishes. Note that edward has made the gains above the kink stop entirely on this graph just to illustrate the point, which will not be strictly true - out of absolute poverty, health gains will continue with higher consumption, though they may be smaller. In Edward's 2006 paper, people across 150 countries averaged a life expectancy of 74 years at the kink. Edward identified the kink as between 2.7 and 3.9 times the World Bank's poverty line. Hickel has updated this to 7.40, which is based on 3.9 - the upper end of Edward's estimates -

times 1.9: the current world bank poverty line. You can fairly critique this approach, but at least the measure is actually connected to a concrete idea of human needs. Even if you go with a lower value it's clear that the measure gives a multiple of the most used cutoff, so poverty is higher than indicated by the line used by the World Bank and by Pinker. The typical response to the admittedly obvious point that a higher poverty line means more poverty is to say that the $1.90 threshold is

only intended to measure extreme poverty, but this misses the point. A poverty threshold should be grounded in human needs and should mark a turning point for when they are fulfilled, as Edward's measure at least tries to do. The $1.90 threshold isn't grounded in a clear idea of human needs so it shouldn't be the World Bank's target and it shouldn't be the threshold used for these graphs. People who have tried to ground the poverty line like this but using different methods have almost universally come up with a higher value, which can change the picture of global poverty. I suspect that Steven Pinker's grasp of all this is pretty shaky. There was an interview where Mehdi Hasan challenged Pinker on his understanding of the numbers and Pinker seemed under-equipped to address the points. Well let's take global poverty-yeah- you have a chapter in the book

on on prosperity. You want to make the case that the world is more prosperous and less poor than ever before and you point to data showing the number of people living on the extreme poverty line, as defined by the World Bank today at $1.90 a day, is down from 2 billion in 1990 to 700 million in 2015. "The world is becoming middle class" you say. But surely you know - I know you know because you're a very clever, well-qualified guy - that there are numerous studies and a number of scholars who dispute that poverty measure as arbitrary, as inaccurate that in reality to quote from a recent academic paper by an anthropologist at the LSE, quote "around 4 billion people remain in poverty today around 2 billion remain hungry more than ever before in history" That-completely irrelevant to which way the the the numbers have gone, of course the definition of absolute of extreme poverty is going to be arbitrary, if you make it higher then more people will be in poverty; make it lower fewer people exactly but no matter what cut off you uh set the direction is downward. Actually, if you look at the work done by Jason Hickel at the LSE, if you take a poverty line of five dollars a billion people have been added to the number of people in on that poverty measure since 1981. The trend shows the exact opposite when you move it to five dollars a day The -uh in terms of the proportion of people absolutely in poverty by that criteria? The sheer number of people A billion people have been added to the poverty total since 1981 Yes but billions of people have been added to the world as a whole, what's relevant is the proportion. But you also used

absolute numbers in your book, you said it's gone down from two billion to seven hundred. Well I, I, I note that the uh by at least the most widely accepted definition of extreme poverty it's interesting that the absolute numbers have declined as well but the main point is the proportion because more people have been added so anything is going to increase. Fortunately, after watching this video you'll be much better equipped than Pinker was! Let's discuss the main points raised by Mehdi in more depth. I want to clarify three main questions in particular:

Unpacking these will take us to the heart of the New Optimist narrative. To take the first point about the value of the cut-off: it's undeniable that the proportion of poor in the world has fallen pretty much whichever line you use, though it's also clear that the decline gets less impressive the higher the line. According to the World Bank's poverty calculator on their website, between 1981 and 2019: Another way of representing this is this animation from Max Roser, which shows the change in the global income distribution, with gains at pretty much every level but fewer at higher levels. We'll return to the issue of global distribution later. Alternative measures such as those created by Robert Allen, who we met earlier, or Martin Ravallion, a prominent economist at the World Bank, try to accommodate disparities in individual countries in their own ways and still find a decline. See their papers if you're interested. The story changes slightly if you use the absolute number of people in poverty instead of the proportion, which brings me to the second point. The proportion of poor people in poverty is the best

measure for looking at changes over time, otherwise you'd have to argue that the state of poverty was better under early industrial capitalism just because total population was so low. There were fewer poor people because there were fewer people, but we don't think of this as a good thing, since so many of the population were impoverished. But absolute values carry some significance too: one person suffering is one person suffering and presumably it doesn't matter to them how many other people exist. Pinker even agrees, stating that at the $1.90 line the absolute number of people in poverty has fallen: But this part of the narrative falls apart with higher poverty lines since at $7.40 a day the absolute number of people in poverty has actually gone up. Turning to the third and final point: should we omit China or other high-performing economies in East Asia? This would seem to be loading the dice because omitting the most successful and populace countries in the world would obviously have an outsized impact on global trends.

If you are asking the simple question of whether poverty is declining globally it makes no sense to exclude China, since it's a fifth of the world's population. But as you might have suspected, debates over the data hide some fundamental political differences. Hickel excludes China in some cases because he is arguing against the neo-liberal narrative that decreasing poverty owes to free markets and globalisation. China is a country with a heavy degree of state intervention, ranging from currency controls to state-owned enterprises to massive public investment. These went directly against neoliberal recommendations from the World Bank and IMF, as did other success stories such as South Korea. By engaging in these policies, China has made not just progress at the lower poverty lines but at the higher ones too, and is one of the few countries that have achieved this.

Pinker is no free marketeer, having stressed the importance of social spending. Social spending, for the elderly, for children, for the sick, for the unlucky, that's not incompatible with a free market and in fact some of the countries with the strongest social safety nets also are the ones with the most economic freedom. And yet...I'd still characterise him as a soft neoliberal. His response to Hickel on this point revealed a lot: Pinker also insisted he was siding with the experts and accused Hickel of being a "Marxist ideologue". Whether you agree with Hickel or not, he is an expert on the poverty data and ultimately Pinker was unable to engage on the detail. You say widely accepted but this is my

point: you don't acknowledge in the book, there's no caveats where you say, for example professor Lant Pritchett, Harvard colleague of yours, a development economist who studies this stuff says "the poverty line shouldn't be 1.90, it should be 12, 15 a day" and when you make that simple statistical change the entire picture of poverty changes and the arguments in your book basically fall apart, do they not? Uh, no I don't think so uh again I mean A statistical change this is the problem relying on data you change the measurement and everything changes Well, no not everything changes because I mean there can be I mean that that's a rather extreme redefinition, that's multiplying by a factor of six. He's one of the world's experts on the subject! You're not, with respect - this is his field. You could have included the caveats and said "look, there's a bunch of experts who don't agree that poverty-" you declare as fact that poverty is falling, plenty of development experts disagree with you is what I'm asking yeah some do but if it's a question of just absolute numbers it's irrelevant, if it's a question of whether we should set the poverty level at two dollars or three dollars that's irrelevant, over a wide range of estimates the picture is the same. Omitting China doesn't change the trend at lower poverty lines like $1.90, but as China has made the most promising

progress at higher poverty lines, omitting it means even the proportion of people in poverty at higher lines has been roughly stagnant. How exactly one would characterise China's economy is the discussion for another video, but the fact that it has resisted the western model of globalisation certainly doesn't sit easily for Pinker's narrative. To summarise: using proportions the World Bank's data show that global poverty is declining at almost any sensible line, though the most impressive decline is at levels that are probably too low. Using absolute numbers poverty has fallen for low lines but increased for high lines. Omitting China, the proportion of people in poverty has fallen noticeably for low poverty lines but only slightly for higher poverty lines. It's useful to know all this but ultimately these debates obscure the more straightforward question asked by Hickel and others: why does poverty still exist? If you see people as just born into poverty naturally and wealth as the aberration, you will be more concerned about proportions and declines over time as humanity gradually escapes the poverty trap. If you see poverty as an aberration enforced

by capitalism or other systems you'll naturally view any remaining poverty as morally indefensible. We have seen that poverty may well not be the natural state of man and wealth creation as we know it has often had adverse consequences for poverty, especially in the early stages. We have seen that the global economy delivers some growth to the poorest but this may not be enough to meet their basic needs, and the countries which have done enough have entered the global economy on their own terms. In order to answer the question of whether poverty should exist at all I next want to turn to the general question of how wealth is distributed.

Hey everyone, my name is Sam and I run a YouTube channel called We're in Hell Now that you're done eating your vegetables with UE, it's time for some nice wishy-washy theatrical lefttube content. This is an excerpt from my video on Pinker where I'm going to talk about happiness and why it's bad. In one of the chapters in Enlightenment Now, Pinker discusses happiness and tries to show that it neatly rises along with GDP to do this he cites quantitative data from happiness researchers but there's a bit of a problem with this. First of all, there are studies that contradict the ones Pinker cites that

show that citizens of wealthier countries are no happier. Pinker relies on one study which does show a correlation between happiness and economic growth. However, for some reason he doesn't include any of the criticisms that have been made about that study, namely that they use too small a sample size. But also, as Pinker discusses, data on happiness are collected by just asking people how happy they are but as Sara Ahmed points out in her book The Promise of Happiness, this is a methodological problem with the study of happiness as a whole, since, when we talk about happiness we don't just mean feeling good but generally think of being happy as synonymous with a well-lived life. To ask someone how happy they are is almost akin to asking them how successful they are, which is far from a neutral question. In addition to hard numbers, Pinker also does a cursory vibe check of

the literature from other time periods and so in my video we're going to look into modern artistic trends too and to do this we're going to be using what is, at least on its face the most mushy feels over reals school of analysis out there: affect theory. Affect theory is an analytic discipline that studies feelings - how they work, how we think of them, and what they are. It's sort of the science of vibes. As as Lauren Berlant, who actually tragically passed away very recently at the age of 63, notes, affect theory can be incredibly useful for analyzing the current moment. Like, for something like The Enlightenment for example since we have historical hindsight, it's a lot easier for us to look back and make sense of its causes, effects who was involved, or if you're Steven Pinker just make a bunch of [ __ ] up. But, in the present moment it's a lot harder to do those kinds of things for instance a lot of scholars think that we are now in the period of post-post-modernism but since we're currently in the middle of that moment it's very hard to say anything definite about it other than that it desperately needs a better name than post-post-modernism. This is where affect

theory can be really useful because one thing that we can know about the present historical period is how it feels and how it feels is... What Berlant argued is that the affect that defines our current moment is what they called 'cruel optimism' and their explanation of this is just the best description of a toxic relationship that I've ever heard: An example of cruel optimism would be something like smoking. You might pick it up to fit in, but ultimately it winds up being an obstacle to that goal by causing you to...die, and then no one wants to hang out at a party with a decomposing corpse. In Ghassan Hage's book Against paranoid nationalism he argues that society can be thought of as a mechanism for distributing hope. An example of how cruel optimism fits into Hage's theories is in a talk Slavoj Zizek gave in London after being caught rifling through the compost in search of dinner, he discussed how the labor movement was unable to prevent the rise of Margaret Thatcher Zizek argued that the left was unable to prevent the working class from voting for Thatcher because while they focused on economic inequalities Thatcher was instead able to provide her voters with the fantasy or as Hage would call it 'hope' of a better future. Thatcher - racistly -argued that there was such a thing as a 'British

character' and that anyone who had the British character had the potential for upward mobility. This promise of a better future was so powerful that it overrode the fact that her policies were directly responsible for worsening the lives of the very people who bought into it. One of the interesting observations Hague makes about this hope distribution system is why countries let in refugees. In addition to providing cheap labor, accepting refugees serves to legitimize a country by showing that they've produced so much hope that they can afford to give some away to the less fortunate. Coming back to Pinker now I think this raises a good question about his book: what and who is Enlightenment Now for? In Jason Hickel, one of Steven Pinker's biggest critics' book The Divide, he mentions a well that was donated by the U.S. in the West Bank

of Palestine the well features a big sign that says it's a gift from the American people but Palestine doesn't need wells - not really - their water shortage comes from the fact that Israel, with the support of the U.S., takes about 90 percent of Palestine's water for settlements and won't let Palestinians deepen their wells to get at what water is left. The well and the sign aren't there to help Palestinians, they're there for Americans to feel good knowing their government has produced so much hope that they can give a little away for free. Pinker's work serves a very similar purpose: to deliver hope to justifying neoliberal capitalism, not for those most negatively affected by it but those enjoying its rewards. Like, giving a copy of Enlightenment Now to someone living on two dollars a day expecting them to be cheered up by the fact that crime in America has been decreasing since the 90s is straight up serial killer [ __ ] and Pinker is explicit about this: Oh my god he admitted! anyway Anyway, for more theatrical, even softer science check out my video about Pinker. Now, back to the rantsona. To put it mildly, Steven Pinker's chapter on inequality leaves a lot to be desired.

It is one-sided and full of strange red herrings that distract the reader. His view of economics in general seems to be filtered largely through libertarians, including instances where he cites more left-wing sources but seems to rely largely on right-wing critiques of them. For example, Pinker's overall view of distribution is summed up nicely by the following passage: Hmm that's an interesting claim because I'm an economist and I never hear anyone speak of these "fallacies". I wonder what his source is? Sowell. Your time will come. Put simply, there's no contradiction between wanting growth

and wanting to redistribute its proceeds. Pinker is presenting a 'false choice' - yeah that's right, I can name fallacies too. And this one's actually real. If discussions about distribution presuppose that wealth exists then it's a good thing wealth does exist. Now we can discuss redistributing it. This was the approach of Thomas Piketty, who Pinker decides to include in his critique: It's generous of Pinker to acknowledge that Piketty, the world leading economist on the subject of inequality, might actually know what he's talking about and just be falling prey to "rhetorical zeal". Piketty's book documents the process of economic growth leading

to increased wealth over time approvingly and in detail. Painful detail. It is literally impossible to miss. Unless your view is based on a quote from an article criticising the book! Here are some other Piketty quotes: (He talks about the measurements we've just covered) Even the quote Pinker uses is part of a section warning not to underestimate the absolute gains by the middle class just because inequality is high.

To sum up, although piketty is clearly concerned about inequality he doesn't commit the so-called lump fallacy for any reason. Piketty just doesn't like the social consequences of uneven growth and favors redistribution, most notably with a wealth tax. We'll return to that later. When he's not misrepresenting people, Pinker makes the case that inequality basically doesn't matter: Of course, it's a fantastic joke and Pinker's rendition does it full justice. But it's quite distracting because it doesn't get at the reasons people are concerned about inequality, something Pinker subtly concedes as the chapter goes on and he has to acknowledge the real arguments against his position. Specifically, what if some of the things Pinker values, like health, have a relationship with inequality? To this end he meanders through a critique of a famous book known as The Spirit Level, which linked a variety of societal ills to inequality including obesity, crime, mental health, and bullying. I am of the view that the original Spirit Level made a limited case for its conclusions and that the authors are too zealous in their quest to link inequality to all social ills. Despite that, there's definitely

more here than Pinker lets on. His treatment is brief and one-sided, mostly accepting the conclusions of a book written shortly after the Spirit Level called the Spirit Level Delusion. No prizes for guessing which side of the debate that author came down on. Pinker says the spirit level theory: I find it hard to process the irony of this coming from a guy who has presented 75 graphs showing things improving over time and attributed them all to 'Enlightenment ideas' - a literal theory of everything from correlations. I mean, at least inequality is actually a measurable independent variable. The major omission by Pinker here is a follow-up book by the same authors called the Inner Level which I found more convincing than its predecessor because it identified status anxiety as a key mechanism for the link between inequality and social problems. This graph shows data from around

30 rich countries on the degree of agreement with the statement "some people look down on me because of my job situation or income" which is taken as a measure of anxiety about your status, on the y-axis. (As the number for status anxiety doesn't have an intuitive interpretation, the authors have just labeled it 'high' and 'low'). Countries are split into those with high inequality - the solid line - medium inequality - the dot dash line - and low inequality - the dashed line. The x-axis goes up the

income distribution for a given type of country, from the poorest in a country on the left to the richest in a country on the right. Status anxiety is higher for the poorest within each country but it is also higher at every income decile for less equal countries. You are more likely to suffer from status anxiety if you are in a low income group or if you are in the same income group in a less equal country. The general idea here is that inequality and relative poverty "get under the skin" and cause various types of psychological and physiological distress. Status anxiety has been shown to increase the levels of cortisol in the blood, a widely used biological measure of stress. Through this mechanism and others it seems that those who are lower on the socioeconomic ladder face additional health problems the relationship between inequality and health outcomes enjoys quite a lot of support in public health as the biologist Robert Sapolsky has summarised: Altogether, this is comprehensive evidence that inequality and relative poverty create problems for people's health through mechanisms such as stress and anxiety, with research ruling out alternative explanations such as reverse causality or lifestyle choices. Sapolsky also points out

that basically the same argument that applies to health can be applied to crime. Here is Pinker's 'intellectual dark web' buddy Jordan Peterson acknowledging this fact: Now, one question is "where's the crime?" and you might think well the crime is where the absolute poverty is high right? Oor the absolute wealth is low that's where the crime is - that's wrong if it's- if things are relatively distributed in an egalitarian manner the male on male crime especially homicide is low and it's also the case where everyone is rich but if you go into places where there's some rich people but not very many and there's a lot of people who are comparatively poor than the male homicide rapes- rates and violent crime rates amp up substantially and it's a consequence of male-on-male competition. None of this is certain of course, but it's a much more credible hypothesis than Pinker gives it credit for. Instead of engaging with this work Pinker chooses to focus on inequality and happiness which is besides the point because happiness makes up a small part of the Spirit Level. Anyway, here he relies on a cross-country study showing inequality

has no effect on self-reported happiness but the study is a bit of an outlier, there is a large literature I am familiar with and Pinker ignores which asks whether people's happiness depends on comparisons of their income with others. A 2008 review by Clark et al lists a few papers: A socially acceptable standard of living is likely to depend on the average income of a society those who are unable to attain this standard may face shame, anxiety, and be shut out of social interaction. This dynamic was noticed by Adam Smith, an Enlightenment thinker if there ever was one: Pinker is more than aware that social interaction is a human need - at one point he describes social isolation as "torture" but he fails to link this to economic inequality it is fair to say that abstract notions of income and wealth inequality can fail to get people's attention possibly because we struggle to comprehend the magnitudes involved or to link them to reality some people have done a fairly good job of trying to bridge this gap in our understanding I think it's often people forget the difference between a millionaire and a billionaire. Counting the numbers to a million would take you 12 days, counting the numbers to a billion would take you 31 years. The scale of a billion dollars is really crazy. So let's say one grain of rice is equivalent to 100k and 10 grains of rice would be then a million. Well, how much is a billion?

That is a billion dollars where each grain of rice is worth 100k. For me at least, regional inequality makes this the most vivid. In my own country of the UK, London and the Southeast have pulled ahead while the North, Wales and Scotland have faced relative decline. By any reasonable measure almost everyone in these areas remains well above absolute poverty. The median income in the

Northwest city of Blackpool puts it at a multiple of even the highest proposed international poverty lines. And yet, the level of deprivation is obvious from a journey through the town centre, where there are empty shops and crumbling infrastructure. The population has an array of health problems, both physical and mental. There are a few opportunitiesthat grant a stable income and those that do are

hard work with long hours. Houses are beset by dirt and damp. Health and education systems are subpar. I could go on. The doctors in Blackpool have taken to calling the condition that ails many of their patients "[ __ ] life syndrome". "[ __ ] life syndrome is clearly not on a par with the absolute poverty experienced by the world's poorest but it is also a condition that most of us understand we wouldn't want any human being to be in, and the name shows that doctors recognise it's something they can't do much about with a 15-minute meeting because it's caused by broader systemic factors.

Pinker is keen to emphasise that measures of economic progress like GDP are actually underestimates of the growth of prosperity because of the availability and quality of goods which didn't even exist in the past like fridges or microwaves. But he misses that despite this growth of consumer goods, day-to-day existence in rich countries can still be a struggle to meet basic needs. This graph shows the proportion of their income people in the UK spend on the basics: housing, food and drink, transport, communication, clothing health and education.

Each bar shows the totals spent on the basics in a year and the different categories are represented by the different shades. Together, basic needs were just under three quarters of consumption in 1988 and just over two thirds of consumption in 2019, a slight decline. You may own a microwave but be continually faced with the threat of eviction or of the electricity which powers the microwave being cut off - this is hardly cause for celebration. Participating meaningfully in a society with a given level of wealth requires access to a certain proportion of that wealth even for the basics because their price scales with average income. This also explains why some of

the world's most deprived people live in unequal middle-income countries like Brazil. It explains why Piketty is concerned about the proportion of wealth the poor have, not just the absolute amount. Contrary to what Steven Pinker says, inequality is a fundamental component of human well-being. It is

intertwined with social inclusion, which is itself a human need. Inequality can lead to stress and anxiety, which is why it has been linked to health outcomes, to crime, and to self-reported happiness. As I mentioned earlier, Pinker is not against all social spending and he even makes some recommendations to expand it, some of which I agree with. His view is probably best summed up

by the philosopher Harry Frankfurt, who he quotes: But in this part of the video we've seen that 'enough' is often relative to the society you're in and cannot be determined by a high income compared to the past. If pinker's review of the effects of inequality is one-sided, his view on its causes is virtually non-existent. He tends to attribute every change in the modern income distribution to the vagaries of markets and globalisation, without discussing specific policies. In this part of the video, I want to look at how existing inequality has come about and what we might do to reduce it. As Thomas Piketty and others have documented, inequality within rich countries has generally gotten worse over the past few decades. One measure of this is the share of income going

to labour - as opposed to capital -shown in this graph over time for the US - the dashed line - the UK - the dotted line - and the G7 - the solid line. The labour share has declined in all of them since the 1970s. I'm choosing the labour share rather than other measures of inequality, which have also increased, for reasons which will become clear shortly. Pinker correctly identifies that the reason some people might be concerned about inequality rising is because that inequality is a reflection of unfairness. People can be incredulous that any one person truly deserves an income hundreds or

thousands of times higher than anybody else as it seems to conflict with basic values about equality. So why does pinker think some people get so rich? Updating a famous thought experiment by the philosopher Robert Nozick he argues that inequality results from voluntary choices: I must confess I've never found Nozick's thought experiment particularly persuasive while each individual in the example consents to giving J K Rowling their own money they don't consent to anyone else giving J K Rowling money. Only a tiny part of the resulting distribution can be said to be voluntary for each person and the thought experiment depends on a switch from individually voluntary to collectively voluntary actions. Wiewed through this lens, inequality is a kind of collective

action problem. Individually we each make market decisions that result in a situation we may not be happy with when they're aggregated. Especially when it results in more rambling and offensive... Fantastic Beasts films.

All of this is a moot point anyway because Pinker's harmonious description of the growth of inequality simply doesn't fit the facts and he actually makes little attempt to establish that it does, instead opting for these thought experiments. When we stop engaging in thought experiments and look at actual things that are happening it's easy to see that the economy is currently designed to funnel money upwards, both globally and within countries. This is a result of deliberate legal, economic, social, and institutional changes. As a simple example, both the 2008 and

coronavirus crisis saw billions of dollars poured into companies which have paid huge bonuses to their executives while neglecting or even shedding workers. To get more detailed on the political choices that have led to existing inequality, let's have a look at membership of unions, which is known to have declined over the past few decades. Smithers, where's that union representative? He's 20 minutes late. I don't know Sir, he hasn't been seen since he promised to 'clean up the union'. Whoa. What the hell? These graphs show union membership and the share of output going to the top 10 of earners over time in the UK on the left and the US on the right. It's clear that for both countries union membership is inversely correlated with the income of the top 10 percent.

Correlations can only take us so far of course but these are pretty striking. A recent paper by Anna Stansbury and Larry Summers investigates this question in more detail and finds that the bargaining power of labour is the biggest factor in explaining the rise of inequality in the USA. Their paper is technically complex but there are a few graphs which illustrate their point nicely. They find that the wage bonus of being in a union has fallen by about 29%. More generally, what they call 'labour rents', which you can think of as labour's share of the surplus of corporations, fell from about 11% in 1985 to about 6% in 2015, as shown by this graph. I encourage you to take these numbers - as with all numbers - with a pinch of salt, but there was an especially interesting part of the paper which I think gets at the crucial question of whether globalisation intensified competition and therefore destroyed the income available to workers. In this view workers lost out simply because their industries had to tighten their

belts in the face of international competition and globalisation is what caused the decline in the domestic middle class. The first graph shows a measure of profitability against a measure of 'import penetration'. It's- it's not funny. It's not- it's not even funny. So what does import penetration mean? It measures the exposure of an industry to international trade. The higher it is, the more likely an industry is to face competition from abroad. In this case the x-axis shows the change in import penetration specifically from low-wage countries. This should capture the rise in the type of international competition which has undercut industries and workers in rich countries.

Each dot on the graph is a particular industry like textiles or furniture the y-axis shows the industry's change in profitability over the same period. As we'd expect, this graph shows that more competition for an industry as shown by the change in low wage import penetration is correlated with a lower change in profits for that industry, with many industries experiencing declining profitability over the period. But what does this mean for labour? Conventional wisdom would have it that exposure to trade intensifies competition and therefore that there is less to go around for both labour and for capital, but this isn't obviously the case. The x-axis in this graph once again measures the change in low-wage import penetration but the y-axis now has the change in the wage premium in an industry - one measure of labour's rents. This is actually higher the more exposed the industry is to international trade, so

labour enjoyed higher rents in the industries most affected by imports coming from low-wage countries. Finally, this graph keeps the change in the wage premium on the y-axis but now the x-axis shows the change in unionisation. A higher wage premium in an industry is correlated with more unionisation in that industry. Together, these graphs show that globalisation does not appear to be associated

with a destruction of labour rents because industries with high competition from low-wage countries still had high wage premiums for their workers. However, the graphs do show that industries with more unions have higher labor incomes. Inequality is all about the bargaining power of labour, whether your industry is facing competition from abroad or not. A recent and thorough report by

the Economic Policy Institute investigates the drivers of inequality in more depth for the USA. Reasons they give for the decline in labour's share of income over the past few decades include: These all have in common that they are deliberate policy choices rather than mystical trends which supposedly underlie everything. Pinker just doesn't engage with this type of evidence on inequality, even the widely discussed stuff like unions and the rise of monopolies.

Buy 'em out boys This is a reflection of how shallow his economic analysis is in general and why you should never get your opinions from libertarians. Understanding this also leads naturally to ways of reducing inequality by increasing wages. We could simply reverse or change these policy decisions without having to design any fancy new policies. Redistribution could also involve higher taxes and transfers to give money from the richer to the poorer. I know that's a

point so obvious that it's barely worth mentioning, but Pinker doesn't seriously consider it. Arguably the most disingenuous part of the book is where he observes that historically, reductions in inequality have been caused by the 'four horsemen' of war, epidemics, revolution, and state collapse and therefore concludes that reductions in inequality are bad. (Or is it when he blames Bernie Sanders supporters for Trump? So much competition!) This just muddies the waters given the numerous sensible policy options available. As this graph shows, there are a wide range of countries that

use taxes and transfers to reduce inequality effectively without going to war. The x-axis shows countries while the y-axis shows their Gini Index, a measure of inequality for each country. You can see a flat horizontal line below which is a dotted vertical line that leads down to a diamond.

The flat line is the income distribution before taxes and transfers and the diamond is the distribution afterwards, with the vertical dotted line measuring the difference between the two. There are a lot of interesting things about this graph. Clearly, every tax system shown is somewhat redistributive: the diamond is below the horizontal line for every country. However, the richer countries on the left have much longer dotted lines while countries on the right like India and Mexico barely redistribute at all. Also interesting is that Germany and Finland, both known for being relatively egalitarian countries, actually have similar pre-tax inequality to countries like the UK and US, who are known for being less equal. I just emphasised the use of institutional changes to reduce inequality before taxes, but clearly direct redistribution must also play a role in reducing inequality for market economies. Despite his red herring of the 'four horsemen' Pinker later implicitly concedes taxes and transfers can reduce inequality like this.

But he has a habit of strawmanning inequality reduction as only taking from the rich rather than also giving to the poor. We saw this with his weird Boris and Igor joke earlier but he repeats it throughout the book and also in the Mehdi Hasan interview: The goal should be- should not be reducing inequality, as if if we got the top one percent to die earlier that would be progress. I'm saying that's the wrong criterion for progress. I don't think anyone's suggesting that

I think that's a straw man noone's suggesting- I know but that's that's an implication of focusing on inequality as the problem as opposed to early death that can be prevented. Those are two very different ways of stating the problem- If you don't recognise the link with inequality which to be fair you don't, although there are other studies that does. When push comes to shove, Pinker is keen to draw the emphasis away from all this in favour of the global distribution of wealth, which he argues has become more equal: He gets this view from the so-called elephant graph from Lakner and Milanovic, depicting the growth in incomes across the global income distribution from the fall of the Berlin Wall up until the global financial crisis. The 'elephant' shape comes because the gains at the very bottom of the global distribution on the left hand of the graph have been low, moving right along the x axis we can see they are much higher for the global middle class, are low again for the middle class of rich countries, and are high again for the very rich. This paints a picture of globalisation as a largely positive, albeit flawed process compressing the global income distribution by creating a much larger global middle class while neglecting the middle classes of the rich world, which have seen high and possibly rising income inequality within their borders. But the elephant graph hides an assumption which is pervasive in these debates: these are relative changes, expressed in percentages. If you look at the raw

changes in income, shown on this graph, the income gains are largely flattened at the bottom of the distribution and the graph takes the familiar 'hockey stick' shape, albeit with a slight bump in the middle due to the impressive growth of China and other Southeast Asian countries. This is also in Lakner and Milanovic's original paper, though the elephant version has been shared more widely. Although incomes rose by sixty percent for both the top one percent and those in the middle of the global income distribution, this was an absolute increase of twenty three thousand dollars for the top one percent but just eight hundred dollars for the middle. The rich gained the same in relative terms but 30 times as much in absolute terms. The elephant shows the former

measurement while the hockey stick shows the latter. Remember this animation showing the global income distribution? Has become more equal it has the same problem: it has been transformed to show relative changes, so moving along the x-axis on the left-hand side increases the amount by less than moving along the x-axis on the right-hand side. The implication of this is pretty clear: almost all of the growth in the global economy was captured by those at the top of the distribution, failing to go to those who need it most. Jason Hickel has calculated it will take 100 years to

eliminate even the most extreme level o

2021-07-28 04:16