Olmec Civilization Using Magnetic Technology Suddenly VANISHES

Deep within the verdant landscapes of Mexico's Gulf Coast, cloaked by the dense canopy of tropical forests, the enigmatic legacy of the Olmec civilization endures. This mysterious culture, flourishing from around 1200 BCE, has long captivated historians, archaeologists, and enthusiasts alike. Known as the "Mother Culture" of Mesoamerica, the Olmecs' sudden emergence and equally abrupt disappearance weave a historical tapestry rich with intrigue and unanswered questions. Nestled in the heartland of what would later become a cradle of ancient civilizations, the Olmecs set the stage for the cultural and spiritual development of the region.

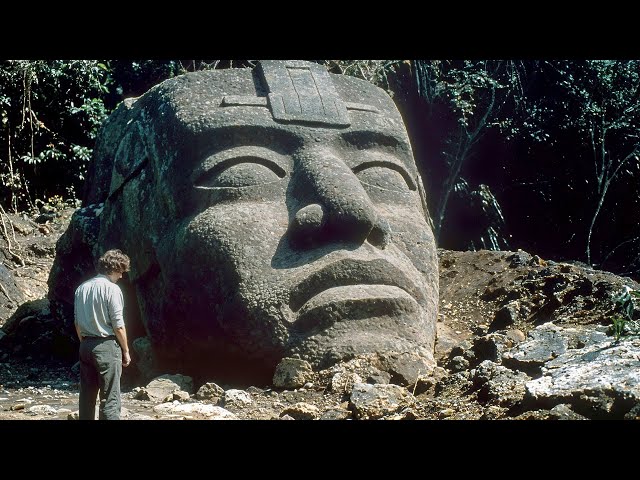

Their influence is undeniable, evidenced in the colossal stone heads, intricate art, and advanced understanding of astronomy and architecture they left behind. These remnants present a historical puzzle that beckons us to delve into the shadows of the ancient world, to unravel the mysteries of a civilization that seems both out of place and time in the pre-Columbian history of the Americas. The legacy of the Olmecs is characterized by monumental achievements that seem to defy the limitations of their era. The construction of massive stone sculptures, some weighing up to several tons, without the aid of metal tools, the wheel, or the horse, poses a significant enigma.

Their sophisticated art, depicting a blend of human and animalistic features, reveals a rich tapestry of religious and cultural beliefs that predate and possibly influenced later civilizations such as the Maya and Aztecs. As the progenitors of Mesoamerican culture, the Olmecs' contributions to the region's cultural heritage are immense. Yet, the origins of their sudden rise to prominence remain shrouded in mystery, sparking a myriad of theories and speculations. The Olmecs' ability to harness their environment, to create complex societal structures and to express themselves through advanced art and architecture, raises profound questions about the evolution of civilization in the ancient Americas.

In their silent stone faces, ruined cities, and artistic expressions, the Olmecs challenge our understanding of history, urging us to keep questioning and exploring the unknown corridors of our past. Their story is not just a tale of what we know but a lingering mystery of what we have yet to uncover. The Mexican Gulf Coast, now known for its lush and fertile landscape, rivers, and diverse wildlife provided the ideal conditions for the rise of a complex civilization. The Olmecs harnessed these resources, creating intricate irrigation systems and engaging in extensive agriculture, which supported their growing population and the development of urban centers.

This early civilization's rapid ascent to complexity raises fundamental questions about the origins and evolution of advanced societies in the ancient world. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Olmec society was not just another gradual step in human development but rather a significant leap. The emergence of the Olmecs, with their advanced societal structures, monumental architecture, and sophisticated art, appears to have occurred with startling speed. This has led scholars to ponder the potential catalysts behind such rapid development. Could there have been external influences, perhaps from distant lands, that catalyzed this sudden cultural blossoming? Or does the story of the Olmecs represent a lost chapter in the history of civilization, one that challenges our conventional understanding of societal evolution? The urban centers of the Olmecs, such as San Lorenzo and La Venta, were marvels of ancient urban planning. These cities were not just political and economic centers; they were also cultural and religious hubs.

The architectural layout of these areas, complete with ceremonial centers, pyramids, and elaborate drainage systems, reflects a high level of societal organization and engineering knowledge. Such advancements hint at a well-structured society with a clear hierarchy, likely including classes of rulers, priests, artisans, and farmers. The question of how the Olmecs achieved such architectural and societal complexity remains. Without any known precursors displaying similar levels of advancement, the Olmecs' achievements in urban planning, art, and social organization seem to emerge almost spontaneously. This raises the intriguing possibility that the Olmecs either developed these complex systems independently, at a remarkably fast pace, or perhaps they were the inheritors of knowledge from an as-yet-undiscovered older civilization.

The Olmecs' accomplishments in other areas, such as art and iconography, further demonstrate their advanced cultural development. Olmec art is characterized by its complexity and sophistication. The motifs and symbols found in their sculptures, cave paintings, and other artifacts suggest a deep understanding of their environment and a rich spiritual life. The iconic Olmec jade figurines, colossal heads, and intricate carvings reveal a society deeply invested in the arts, one that likely held artists and artisans in high esteem. These artistic expressions not only reflect the Olmecs' daily life but also provide insights into their beliefs and worldview. The recurrent depictions of jaguars, for instance, point to the significance of this animal in their cosmology, possibly symbolizing power and the natural world's spirit.

Such artistic themes may also suggest a belief system that included shamanic practices and a deep connection to nature, elements that would profoundly influence later Mesoamerican cultures. The sudden emergence and rapid development of the Olmec civilization pose as many questions as they provide answers. Their ability to create a structured and complex society, their architectural ingenuity, and their profound artistic expressions all suggest that the Olmecs were not merely the beneficiaries of conducive environmental conditions but were also innovators and perhaps even the recipients of knowledge from unknown sources. This mystery at the heart of the Olmec civilization continues to challenge and inspire scholars, offering a tantalizing glimpse into the depths of human history and the potential for lost chapters waiting to be discovered. Their society was likely marked by a clear hierarchy, likely consisting of rulers, priests, and other elites, whose authority and influence are evident in the remnants of their cities and monumental sculptures.

The Olmec cities, like San Lorenzo and La Venta, stand as testaments to their architectural prowess and urban planning. These were not merely centers of habitation but served as the epicenters of religious, cultural, and political life. In Olmec society, religion played a paramount role. The intricacy of their art, with its frequent depictions of deities and supernatural entities, reveals a deep spiritual world.

Their gods often bore anthropomorphic features, blending human and animal characteristics, suggesting a belief system that revered the forces of nature and its various manifestations. The Jaguar, for instance, features prominently in Olmec art and is believed to have been a central figure in their mythology, symbolizing strength, ferocity, and perhaps a connection to the spiritual realm. The layout of Olmec cities further underscores their cultural and religious significance. Central plazas, massive altars, and pyramidal structures suggest places of communal gathering, worship, and perhaps even astronomical observations. These spaces were likely used for ceremonies and rituals, integral to maintaining the social and cosmological order. The alignment of these structures, along with various artifacts, indicates that the Olmecs had a sophisticated understanding of astronomy, an impressive feat that would have required considerable observational skills and mathematical knowledge.

Moreover, the Olmecs are credited with early developments in the Mesoamerican ballgame, which held deep religious and social significance in later cultures like the Maya and Aztec. This game, more than mere entertainment, was imbued with symbolic meaning and was often associated with themes of life, death, and rebirth, further highlighting the depth of the Olmec cultural and religious ideology. The social structure of the Olmec world likely revolved around a central authority figure or a ruling class, who wielded power both in the spiritual and political realms. The existence of large-scale constructions, such as the colossal heads, and the organization required for their creation and transportation, point to a society with a well-organized workforce and a complex social hierarchy. Trade and craftsmanship also played a significant role in Olmec society. The discovery of artifacts made from materials not native to the Olmec heartland suggests that they engaged in long-distance trade with other regions.

Items such as jade, obsidian, and even magnetite were crafted into intricate pieces of jewelry, tools, and ceremonial objects, indicating a high level of skill and artistry. In essence, all of these discoveries are indicative of their advanced state and also of their ability to harness and integrate their environmental and human resources to create a civilization that would lay the groundwork for future Mesoamerican societies. The art of the Olmec civilization is a window into a world rich in symbolism, spirituality, and complexity. Perhaps the most iconic and mystifying aspect of Olmec art is the colossal stone heads, crafted with remarkable skill from basalt. These heads, often interpreted as representations of rulers or deities, are not only feats of engineering but are also imbued with deep cultural significance. The facial features of these sculptures, distinct and individualized, may represent the Olmec's ideals of leadership or divinity.

Their sheer size and the effort required to produce them suggest that they were of immense importance to the Olmecs, possibly serving as spiritual guardians or symbols of power and authority. Another fascinating discovery regarding the Olmec heads was that some of them exhibited magnetic properties. The basalt volcanic rock from which they are carved is known to acquire magnetism as it cools, suggesting a deliberate choice by the Olmecs.

The question arises: Why would a civilization in an era devoid of modern scientific knowledge select magnetic stones for its most significant monuments? This choice indicates a level of understanding that goes beyond mere aesthetic or ceremonial purposes. One of the most compelling pieces of evidence was unearthed in Izapa, a site corresponding to the late formative period from 300 BC. Here, archaeologists discovered a carved stone turtle head which exhibited magnetic properties. Intriguingly, one of the magnetic poles was found coinciding with the snout of the animal sculpture. This discovery indicates a sophisticated level of understanding by the Olmecs.

Further evidence of the Olmecs' knowledge of magnetism comes from the coastal plain of Guatemala. Here, a statue of a jaguar was found with magnetic poles in each raised paw. Additionally, a crude statue depicting two seated men, carved from a single block of stone, exhibited magnetic poles on either side of the navel. These discoveries collectively paint a picture of a civilization that was not only artistically and culturally rich but also possessed a remarkable understanding of natural sciences, particularly magnetism.

The turning point in studying Olmec magnetism came when researchers from Harvard, Yale, and MIT turned their attention to these ancient sculptures. Employing more sophisticated and accurate tools than those used in previous studies, they embarked on a detailed examination of the Olmec statues. This multidisciplinary approach combined archaeology with advanced scientific analysis, offering a new perspective on the Olmecs' knowledge and use of magnetism. The findings of this comprehensive study were published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, marking a significant contribution to our understanding of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations.

The research detailed how the team discovered significant magnetic anomalies in specific regions of the Olmec sculptures, particularly in the pot belly statues and the head statues. The researchers found that the magnetic anomalies were not randomly distributed but were strategically placed in anatomically significant areas of the sculptures. For instance, in the pot belly statues, significant magnetic anomalies were discovered in the naval area, and in the head statues, these anomalies were found in the right temple, forward of the ear. The researchers conducted a thorough statistical analysis to support their findings.

They concluded that the consistent collocation of magnetic anomalies with specific anatomical features was highly unlikely to be a result of random distribution. This analysis reinforced the theory that the Olmecs intentionally selected and worked with magnetized stones. The deliberate use of magnetized stones in their sculptures indicates a level of sophistication and knowledge that was previously unappreciated.

One of the most captivating theories is that the Olmecs might have used magnetic levitation to transport these enormous stones. Magnetic levitation involves using magnetic forces to counteract gravity, allowing an object to float or move without physical contact with the ground. In modern times, this principle is used in technologies like maglev trains which achieve high speeds and efficient travel by floating above tracks using powerful magnets. Applying this concept to the Olmecs, some speculate that they could have understood and utilized the repelling forces of magnets to ease the transportation of the colossal heads. This theory suggests that the Olmecs might have placed these stones on a series of tracks or pathways lined with materials possessing opposing magnetic poles, thereby reducing friction, and allowing for smoother movement.

Another possibility is that the Olmecs used the magnetic properties of the basalt for navigation or alignment purposes. Some researchers have suggested that the positioning of the colossal heads and other structures could be aligned with magnetic fields or celestial bodies, serving as a form of ancient compass or astronomical guide. The distinct characteristics of these stone heads raised many theories. Among these theories is the provocative idea that the Olmecs may have had connections to Africa.

This theory, while not widely accepted in mainstream academia, continues to spark debate and interest due to its implications for pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. The African origin theory gained traction in modern times when José Melgar, who discovered one of the Olmec colossal heads in 1862, noted its seemingly African features. The heads, some of which are over nine feet tall and weigh several tons, are characterized by broad noses, full lips, and other facial characteristics that some observers have linked to African physiognomy. This observation led to the speculation that the Olmecs might have had contact with, or even been directly descended from, African peoples. Perhaps one of the most vocal proponents of this theory was Ivan Van Sertima, a Guyanese-born American historian and writer. In his 1976 book, "They Came Before Columbus," Van Sertima argued that the African presence in the Americas predated Columbus and that Africans had made significant contributions to the development of the Olmec civilization.

He cited the colossal heads and other archaeological and anthropological evidence as indicators of this trans-Atlantic connection. Critics of this theory, however, point out several challenges. Mainstream scientists and scholars argue that there is no direct genetic evidence linking the Olmecs to African populations.

Studies of DNA from Native American people from the region where the Olmec civilization flourished have not shown any markers that would indicate African ancestry during the time period of the Olmec civilization. In addition, scholars point out that the facial features found on the colossal heads are not exclusively African, and can also be seen among the native populations of the Americas. They argue that the Olmec artists may have been simply representing the features of the people around them, rather than depicting foreign visitors or settlers. The argument extends to cultural and technological aspects as well, noting that there is no conclusive evidence of African influence in Olmec pottery, tools, or societal structures that would suggest direct contact or migration. Furthermore, the theory of African origins or influence does not align with what is known about the maritime capabilities of African societies at the time of the Olmecs. Transatlantic voyages would have required navigation and shipbuilding technologies that were not yet developed in African civilizations during the era of the Olmec.

While the theory of an African origin or influence on the Olmec civilization captures the imagination and invites speculation about prehistoric intercontinental connections, it remains outside the mainstream academic view due to the lack of genetic, cultural, and technological evidence. The debate over the origins of the Olmecs, however, underscores the enduring allure of this ancient civilization and the mysteries that continue to surround it. It reflects a broader curiosity about the extent of human interactions in the ancient world and the possibilities of cultural exchanges that are yet to be fully understood or discovered. Another aspect of the Olmec heritage that links them to the civilizations beyond the Atlantic, is the fascinating symbol of the feathered serpent, a central icon in Central American mythology, notably associated with Quetzalcoatl. An early depiction of this symbol in La Venta raised many questions among researchers.

The feathered serpent symbolizing the bringer of civilization is a recurring theme in Mesoamerican mythology and is intricately linked to architectural wonders such as the pyramid at Chichen Itza. Many open-minded thinkers believe that this carving is an actual depiction of an otherworldly being operating some sort of flying vehicle, similar to the Vimanas of ancient Hindu mythology. More grounded researchers like Graham Hancock, however, don't focus on the vehicle itself but on the mysterious bag held by the deity. For this reason, an intriguing aspect of Hancock's discussion is the comparison of the Olmec civilization with other ancient cultures, notably the Sumerians and the builders of Gobekli Tepe.

He notes the presence of similar motifs, such as the 'man bags' held by figures in these diverse cultures, suggesting a possible interconnectedness or shared symbolism across vast geographical and temporal distances. These 'man bags' are seen as potential indicators of a group of beings who might have traveled the world, impacting various cultures along their journey and bringing advanced civilization everywhere they appear. Hancock believes that the Olmec society may have been a part of a larger, interconnected global civilization. The handbag motive in all of these advanced ancient cultures suggests that these bringers of knowledge are not just an isolated phenomenon but a potentially pivotal chapter in a larger story of ancient human civilization.

They urge us to consider broader possibilities in the interconnected history of ancient cultures. The decline of the Olmec civilization, occurring around 400 BCE, is as enigmatic as their rise to prominence. This once-flourishing civilization seemingly vanished, leaving behind a landscape of abandoned cities and destroyed artifacts.

Yet the reason for their vanishment remains a mystery. The decline of a civilization so advanced and developed for its time marked a significant turning point in Mesoamerican history. The disappearance of the Olmec people and their knowledge likely influenced the development of subsequent civilizations in the region. Nevertheless, a large portion of their knowledge was inherited in the works of the Maya, the Aztecs, and other Mesoamerican cultures that rose to prominence after the fall of the Olmecs. In summary, the decline of the Olmec civilization remains a topic of debate among scholars.

How can a civilization so advanced disappear without a trace? A civilization that left such an indelible mark on the history of the Americas. As we reflect upon the Olmec civilization, we are confronted with a narrative that is as rich in cultural and historical significance as it is enigmatic. The Olmecs, remembered as the "Mother Culture" of Mesoamerica, have left a legacy that challenges our understanding of ancient civilizations and continues to inspire both awe and curiosity. Their achievements in architecture, art, and social organization, set against the backdrop of their mysterious disappearance, offer a compelling glimpse into the complexities of early human societies.

The colossal stone heads, the intricately carved jade figurines, and the remnants of their grand cities stand as testaments to their advanced state of development and their skillful manipulation of both their environment and resources. These achievements raise profound questions about the origins and capabilities of this ancient civilization. How did they develop such sophisticated art and architecture? What depths of knowledge did they possess about the world around them, and how did they acquire it? Moreover, the sudden decline of the Olmec civilization adds a layer of intrigue to their story.

Each discovery made in the heartland of the Olmec territory brings us closer to understanding their place in the grand narrative of human history. Yet, much remains unknown. The legacy of the Olmecs, therefore, is not just a tale of an ancient people who once thrived in the tropical lowlands of Mexico. It is a narrative that compels us to keep questioning, to keep exploring the unknown corridors of our past, and to remain open to the myriad possibilities that history can offer. As we continue to unearth their secrets, the Olmecs remind us that history is a mosaic of human experiences, where each piece holds the potential to change our understanding of the whole.

Their story, woven into the fabric of Mesoamerican history, challenges us to look beyond the surface and to appreciate the profound depth and complexity of the human journey.

2023-12-06