Mudd Center • The Ethics of Technology speaker Virginia Eubanks

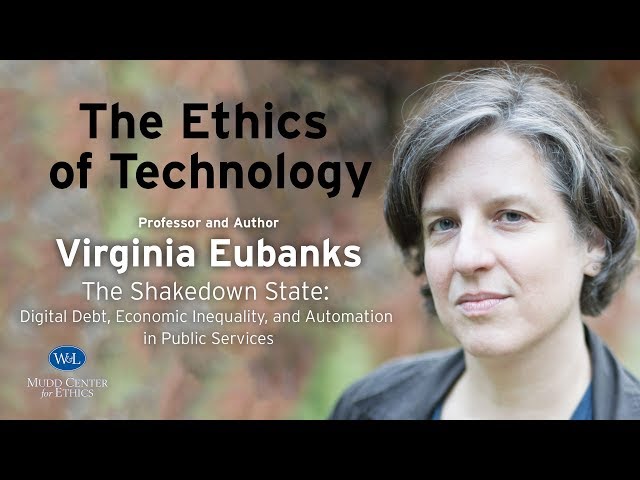

You. We. Can say like a 50 percent return rate on the controls that we know that about half of them I would, be seeing. And. That means that the flavor secretary. Yes it have the one female, squirter Moscow. You. You. You. You. Welcome. Welcome. To the fifth installment of the Roger Mudd Center. Series, on the ethics of Technology. Some. Of you have attended all or some. Of the previous, installments. Beginning. In September. Remember. When Josephine, Johnston, talked. About gene editing and, CRISPR. Technology. Then. In October professor. Jeff Smith, talked. About the relentless, changes, in technology. And the, inability. Of, ethical. Frameworks, to keep pace. That. Was followed, by professor, Ron Arkans talk on, robotics. And the work of the mobile, robot, lab at Georgia Tech. Most. Recently, Cornell, Tech professor, Helen Nissenbaum. Spoke. On privacy, and a technological. Age. Elaborating. Her theory, of privacy, as contextual. Integrity. Well. Our guest today is Virginia, Eubanks. Associate. Professor of political science at, the, University, at Albany, State. University, of New York, she's. The author of the. Beautifully. Written and truly. Eye-opening book. Automating. Inequality. How. High tech tools. Profile. Police. And punished, the poor published. By, st. Martin's Press in 2018. This. Book one the Lillian, Smith book award of the, Southern Regional Council. And Fordham. University's. Magan, uns Center Book Prize for. Social, and ethical. Relevance. In communications. Technology. Research. The. Magana Center, cited, the book's humanity. The. Books humanity. As the. Reason it earned that. Distinguished, prize, the. New York Times called the book riveting, another. Reviewer, wrote that it is quote one of the most important, recent books on the. Social, implications, of information, technology. For. Marginalized. Populations. In the US. Professor. Eubanks, is also the author of an earlier work. Digital. Dead end fighting. For justice, in an Information. Age. Published. By MIT press. One. Reviewer, wrote that, that book quote. Offers, a critical, and constructive agenda. For. The design, of an information, society, where. People matter. Professor. Eubanks, PhD, in science and technology studies is, from. Rensselaer, Polytechnic Institute. She's. A member of Albany's, department, of women's gender, and sexuality. Studies, her. Courses, have included, class poverty. And politics, in the US and. Science. Technology, and social justice. Her. Pathway, to academia, and now. To, investigative. Journalism. Has. Been a fascinating, journey. Building. On her history of activism, for, welfare rights, and economic. Justice for. Example she's been active in the community Technology. Center movements, in the. San Francisco Bay, Area and in. Troy New York a, wonderful. Section of automating. Inequality. Ties. Her deep concern, about the, digital poorhouse. To. The message of dr. King, in the 1960s. Anyway. I won't, say any more we, are pleased to host professor Eubanks, visit to this Kent campus, so please join me in welcoming her. Thank. You Bryan that was a without. Spoil, without, any spoilers, a. Really. Generous, welcome. A really generous. Overview. Of the, last couple years of my life so thank you for that thanks. For the invitation from the mud center I'm thanks to Amy for all of her incredible work getting my physical body here, in. One piece and. Thanks to all of you who. I hope we're. Excited for the talk and not just looking to get in out of the cold. But. If you were just looking to get in out of the cold that's good too oh and. Welcome I'm really excited that we're gonna spend some time together. This. Evening talking. About the. Ethics, of new technology, the. Relationship, to economic, inequality. In. The United States so. I'm gonna do a couple of things today, I'm, gonna talk, a tiny bit about history. Particularly, about the history of this thing called the county poorhouse, I'm, gonna talk a little bit about my, most recent book automating, inequality, and. Specifically. About some of the patterns that. Sort. Of flow through the different stories I tell in that book and then I'm gonna introduce some sort of new material, that I've done just in the last couple of months on.

Automated. Debt collection, in public services, and then we're gonna come back to like what's. The big idea, so, that's a lot to try to get through so I'm gonna I'm, gonna enroll, you, and helping me keeping, us all happy which. Is every once in a while I'm gonna check in with you and if everybody's, still doing okay you give me happy twinkle fingers and, if, everybody's, starting to fade your finger should start going horizontal. And if you just really want me to go away so we can all go to dinner and. Then downward, twinkle fingers okay on that and that's fine it doesn't hurt my feelings it's like a legitimate, temperature. Test of the room so yeah we're happy to keep going oh my god you're starting to lose me oh please shut up lady so, we can all leave okay are we good with that happy. Twinkle fingers and for good with that, there. We go thank you okay. So, I'm. Really excited to be here. What I want to talk about is. This thing that I call in the book the digital, poorhouse, which, is an invisible, institution. That's made up of things like, decision-making. Algorithms. Automated. Eligibility, processes. And, statistical. Models in our nation's social service systems or. Social programs and. I want to talk today specifically. About how the rise of these new, tools really. Responds. To and recreates, a narrative, of austerity. That is a story, that we tell ourselves about, how, there's not enough, for, everyone and we have to make really hard choices, between. Who will be allowed to meet. Their basic human needs and who. Will not so. We often when we talk about sort, of the newest sexiest, technology, whether that's artificial intelligence, or machine. Learning. Algorithm. Ik decision making we like to talk about them as disruptors. But, one of the things that I think is really important, to understand, about the digital tools specifically. In public services, is that, they're really much more evolution. Than revolution, and their, roots go really, far back in our history at, least to 1820. I think, before but, blessed, editor, Elizabeth, DISA guard of my book who, refused to let me have a 90, page chapter, of the first 600 years of poverty policy, starting, a popular book. Helped. Me shave it down somewhat, this is the point at which I we always thank her for. Not forcing, anyone to read 90 pages of history at. The beginning of a book about technology. Um. So I just want to talk about one, moment, in the history today, and. That is a moment around 1819.

When, There was a really crushing, economic, depression, in the United States so this really big. Financial. Disruption. And. Economic. Elites, of the time responded. As they often do, by. Commissioning, a bunch of studies. See. This is really funny so in I do a lot of talks in non-academic. Locations. And in a non-academic room, that's a joke and everybody, laughs. It's. Really funny though when you come when you tell that joke at a college nobody laughs. Just have a moment of self-reflection about, why we don't think that's funny, huh. Okay. So. Anyway, they've commissioned all these surveys the surveys basically, asked like what's. The real problem, right is the real problem. Economic. Suffering, the fact that people don't have enough, to to, eat is it poverty, or is, it what they called at the time popper. ISM popper. ISM basically, meant dependence. On public benefits so, the question, was basically is the problem that people are suffering from. This economic dislocation, or is the problem that they're asking, for help from public sources and, what, do you think this surveys all came back saying. The. Problem was popper, ISM right the problem is not that people are poor the problem is that poor people are asking for help and so, they and they invented a new technology at, of. The moment a brick-and-mortar institution. Called the poorhouse the county poorhouse the. County poorhouse was basically, a physical, institution. For incarcerating. People as. A condition. Of receiving public, aid so, before, that when people were given what was called outdoor Aid meaning, they actually received help in their homes I know it's a little confusing but, they mean outside of an institution um this, was called Indore relief meaning, in order to receive any kind of help you, had to basically check, yourself, in to, a poorhouse and while, they were technically. Voluntary. And they were certainly, not, consensual. Institutions. This is a really, hard choice you, could be by the way you could be sentenced to the poorhouse she could be sent there by your family, particularly. If you're a lady who is like. A little too sexually adventurous. You. Could be arrested. And sent to the poorhouse for things like vagrancy, or begging but. Many people entered in conditions. That were technically, voluntary. But. Entering the poorhouse, meant. Losing, a bunch of your other rights so the right to marry, the. Right to hold office. And, the right to vote if. You had those rights at the time this is 1819, so certainly not everybody had those rights. Parents. Who were entering the poorhouse were generally separated, from their children and their children were sent to be sort of. Rehabilitated. By working with. Middle-class, families, as domestic, or agricultural, labor often, for free in. Binding. Labor. Contracts, and. The death rates that these it's some of the worst of these institutions, was something like thirty percent a year so like a third of the people who entered the poorhouse every year died, so this was no small choice. To enter the poorhouse people were really taking their lives, in their hands yours, by the way was on the not surprisingly, named poor house Road, which. Is near pink tinker's, Ridge about a mile and a half away from tinker's, Ridge about a little, bit north of here I haven't found it yet this is the weird tourism. I do I have every new place I go I'm like where was the county poorhouse and I go see it but. I hear that the supervisors, house still exists and if anyone knows where it is tell me after the talk so I can go there tomorrow, so. I use this metaphor of the digital poorhouse in the book to, illustrate what I sort of think of as like the deep social, programming, that we see in the new tools arising. In public services, across the country and at the heart is really this decision, we made in the 1820s a decision. That public service, programs, first, and most important, job is to, do a kind of moral, diagnosis. To, decide, who. Deserves support. And who is undeserving. To, divert the able, to, enforce, work, rather.

Than Saying what a public service program should, do is put a universal, floor under us all and that deep social programming, is something we see coming up over, and over again in the, new tools that I discuss, in the book so, talk about three different systems in the book the first is, an attempt to automate, all of the eligibility, processes, for the state of Indiana's, welfare programs, that's, TANF, or cash assistance snap. What, used to be called food stamps and. Medicaid. The. Second story I tell is about. A. Tool, whose proponents, call it the match.com of. Homeless. Services basically. It's a tool called the coordinated, entry system it's, supposed to match the most vulnerable unhoused, people, with, the most appropriate, available. Housing resource, and I reported that story in Los Angeles County and, finally. I tell. The story of a statistic, model, that's supposed to be able to predict. Which, children might be victims, of abuse or neglect in the future in Allegheny. County which, is the county where, Pittsburgh is in Pennsylvania. And. So what I want to do is sort of step through the three big points or. Three of the big points of the book and tell you a little bit about each of those cases and then we're gonna move to the, some. Of the newer stuff how, are we doing we still okay oh, you're. Still awake great. So. The first point I want to talk about a little bit is about how, these systems automate, austerity. So the, sort of this deep social programming, that I'm talking about in these tools. Leads. To the, creation of systems, that. Whose. Designers. Say are that they're simply responding. To a lack of resources, or responding, to the conditions, of austerity, but, the reality, is that. They, because. These tools assume. Austerity. They actually, recreate, it and so, for. Example in Indiana, I tell the story the book is actually dedicated to, a young, little. Girl disabled, little girl named Sophie stipes, and. When Sophie was six she received a letter from the state of Indiana that. Explained, that she'd be losing, her Medicaid, because. She had quote failed to cooperate in, establishing, eligibility, for the program and, this. Happened just as she was beginning. To gain weight on, par, with her, age group for the first time in her life she had recently had a gastrointestinal. Feeding, tube. Implanted. And. She was learning to walk for the first time, so. Her family the stipes family, was caught up in an, attempt to automate, all of the eligibility processes, for the welfare programs in the state of Indiana so, in 2006. Then Governor mitch, Daniels, signed, what was eventually a 1.3 4 billion.

With A B billion, dollar contract. With a consortium of high tech companies that included, IBM, and ACS, to. Create a system, that replaced, the hands-on, work, of local, County, caseworkers, in the welfare system with. Online, applications, and private, regionalised, call, centers. And what that felt like on. The front line from the point of view of, workers. Was. That. Where. The system, had worked in the past in on, what's known as a case, based. System, or a caseload system, where. Caseworkers. Were responsible. For sort of a docket, of families, who, they followed, over time who they often developed relationships with, over time they, moved to what's known as a task based, system, meaning. That they're sort of computerized, workflow. System, split. All the, families. Up into different tasks. Different jobs and just sent the, the next, job to the next available worker, what. That felt like for caseworkers, was that their. Relationship. With clients was really. Deeply disrupted. And. Also their knowledge. Of the system particularly their knowledge of local resources, was, really not they. Weren't able to use it anymore so they were able to tell a caller, on the phone like, it looks like you're not gonna be eligible, for food stamps but. They weren't able to say oh and, I also know your town there's a food pantry that's open Tuesday nights you know you can go get resources there, from. The point of view of applicants. It felt, like every. Single time you called you talked to a brand new person no, one was responsible for, getting, your case through the system correctly, and if anyone, made a mistake, it ended up landing on you as your fault your problem, and your responsibility. To solve so. The result was a million, benefits, denials, in the first three years of this experiment, it was a fifty-four percent increase, from the three years before the experiment, and. Just about every, case, that. Was, denied or canceled was, denied or cancelled for this sort, of catch-all, reason, failure. To cooperate in, establishing. Eligibility. And that just meant that somebody somewhere in the process had made a mistake it might have been the applicant, they might have forgotten to sign page 25, of a 34 page application. But, it might have been the. Technology, itself, there were sort of consistent, problems, at the document, center where things got scanned in upside-down or. You. Know you were scanning a photocopy, of a driver's. Lay and all you got was like a black box instead, of any of the information that you'd get on a driver's license, or you, could have gotten bad. Advice. Or bad policy. Advice from the. Sort of poorly trained folks who are working in the call center, but any kind of mistake with the application, was interpreted, by the system, as an, affirmative failure. To cooperate in, the process, which. Was under, current under, the current policy. Enough. Reason, to deny you public. Benefits. So. Also. The failure to cooperate notices. That people received. Only said that there was an error not, what it was so you didn't get a notice that said you didn't sign this so that's the problem you got a notice that said you failed to cooperate you have, ten days, and. That, left. Because. The system had severed the relationship between caseworkers. And clients that really, guaranteed. That the burden, of finding, mistakes, and fixing them fell. On, really. Squarely, and solely on the shoulders, of, applicants. Who were some of the state's, most vulnerable people. So. This created an enormous burden for. Poor working-class families in Indiana um so Kim Stipe Sophie's, mom told, me when I was in, Indiana, she said during that time my. Mind was muddled, because it was so stressful all.

My Focus was on getting Sophie, back on that Medicaid, then, crying afterwards, because everyone was calling us white trash and moochers, it was like being sucked up into this vacuum of nothingness. So. Um clearly, the worst impacts, of the system landed. On folks. Who are applying for benefits. Or who who lost their benefits during during the experiment, but. The experiment also cost the state more broadly and this is where we get to this point about automating. Austerity, though. The system, was designed. Rationalized. As a way to cut costs, to, make sure that there are resources available for people who really needed it, the. Experiment, ended up costing, the state. Astronomical. Amounts, of money so after, really intense public pressure one of the good news stories in this book is that the people of Indiana really pushed back on this system and forced, the governor to, change. His mind and to back out of the contract three, years into a ten-year contract. And. He called the, system. Quote a good idea that just didn't work out in practice. But, then IBM sued, the state for, breach of contract and. At least in the first round through the courts won so, not only was allowed to keep the first half billion dollars, that they had collected but, was also initially awarded an extra fifty million dollars in penalties because. The state had breached the contract, now. That stayed in the courts for about nine years and in the end the state got back one hundred and fifty million dollars. But. All. Of, the money that. All of the resources that were spent to create implement. And legally, defend that system, could. Have just gone to benefits, right. To the folks who really needed it so. The second point I want to make from the book is that. For. Those folks, those administrators, those designers. Who. Don't use sort of efficiency, and cost savings, it's the first and most important, reason that these systems are being created, the, second reason that people most often give is because, they fight bias they fight human bias in systems. Where it really matters, whether. Or not there's. Racial. Or or or. Class assumptions. Going on that, are denying people benefits, to which they're entitled by. Law um. So. In Allegheny, County, Pennsylvania. I. Spoke, with Patrick. Grieve and angel Shepard who, are these sort of engaged, in creative, parents.

Really. Extraordinary people in many ways, who. Have never less been red-flagged by. For. Several times by the county's. Child Protective Services Agency. In Allegheny, County it's, called CYF, children. Youth and families, for. Neglect. And. Patrick. For example. Was. Investigated. For neglect, when his, daughter. What, became ill and he took her to the emergency room. When. He got they prescribed, antibiotics. When he left the emergency, room he couldn't afford to, you fill, the prescription, and. When his daughter got worse a couple of days later he took her back to the emergency room and the nurse, there reported, him for medical neglect so, he was investigated, for neglect, by Children Youth and Family Services, and. Angels. Daughter Harriet. Has. Been sort of in and out of the Children Youth and Family Services, system. Since early in her life, or, early in her life there was someone in the neighborhood who called on their family a lot there's a hotline, where you can call when you suspect, neglect. Or abuse. Angel. And Patrick suspect, it was a neighbor who had some, kind of other beef with them who was sort of trying to create trouble for them so Harriet. Got called on a bunch of times on this anonymous, tipline. The. Caller, said she was sort of down the block teasing. A dog that she wasn't getting needed, medication, that she wasn't being fed. Or clothed or bathe regularly and. Each time there was a report, Children. Youth and Family Services, came out to the house looked. Under all the beds and in all the cupboards requested. Access to the medical records, for the family and every, time they. Came out they found that there was nothing. Going on and closed the case. But. The. The, information from all these investigations. Has. Been put into a data warehouse, that the county has been building since 1999. And. The the. Model, that I talk about in the book the Allegheny family screening tool is built, on top of this data warehouse and as, of the writing of the book the data warehouse can shrink contained, a billion, records more. Than 800, for every individual, living in Allegheny, County so. Data extracts, were regularly collected, from, agencies. Like adult and juvenile probation the. Jails and the prisons county. Mental health services, the state office of income maintenance which is like the welfare, programs there the, public schools and other agencies, that primarily, serve poor. Working-class families, so. The issue that angel. And Patrick, talked to me about was, that they felt like because they had interacted, with the children youth and family services, system in the past they. Were they. Were under extra, scrutiny by the agency, because there was so much data about them in the system and, so they felt like every time they reached out for support with their parenting, or for their household that.

Each. Decision, was like a little mini algebra, experiment. Where they were like well. Does. The the. Cost. Of, get does the the, benefit, that's going to come from this service, outweigh. The possible risk were running of pushing, our risk score up in this, predictive. Model, meaning. That we're increasing, the risk that our family, will be investigated. Again and, we might lose our. Daughter to, to. Foster the foster care system, because. The limits of that data set of that data warehouse, really. Influenced what the the model is able to predict, so, I spent a bunch of time in Allegheny. County both, with parents. Families, who have been impacted by the system. And. With. Frontline workers in the system who are called intake screeners, and intake. Screeners, basically, take those phone calls that I talked about earlier and make a really tough decision about, whether. Families should be screened in for a full investigation or, not what's. So interesting about this story is that parents, really had a fear of what are known as false. Positive. Problems. In this predict. Predictive, model meaning, that the system was going to see harm where, no harm actually, existed. The. Intake, call screeners, interestingly, were. We're, also concerned, about the limitations, of this data set but, they were concerned about false negatives, problems, because, this system had no information about professional, middle-class families, call. Screeners, were really concerned that the kinds of harms that happen, around abuse, and neglect in middle-class families, couldn't. Be seen by the system, and wouldn't be predicted, by the system, so both, parents. And, frontline. Workers, were really concerned about the same thing which, is that the data set is so limited, in this tool that, is unable to really, understand. Who, is most at risk, so. Though, the, systems. Are sort of sold to, county. And state agencies, as removing, bias as like, keeping, an eye on frontline. Caseworkers. And their due in making the, reality, is they don't remove, bias from the system, they really, just move, it they, move it from. Frontline, caseworkers. These call screeners, who, by the way are the most working, class the most female in the most racially diverse part of that workforce and send. It off to the. Computer. Scientists, and economists who, are building the model most. Of whom in this case are very. Well-intentioned and very smart people who, live very very, far, away from Pittsburgh. And often, don't have the contextual, information they, need to, build models, that are appropriate. For. The. Actual needs of a community. So. Part of the problem is that the designers, of these systems really only see bias as a property of individuals they. Only understand, biases, like flawed decision, making by, call. Screeners, but, the reality, is call. Screening is not the point at which bias is entering the system the. Bias actually enters this system at the point at which the community, calls, on, a family. So. Black. And biracial families, in Allegheny County are called, on are reported, three, and a half times more often than white families even if you control for economic, status, and. That's not the point at which the system is intervening, because it's not really a data problem that's sort of a big cultural, problem, a big, conversation, we need to have together, about. What, we think a safe and healthy family looks like and why, we think safe, and family, as safe and healthy families, look. Both white and wealthy. But. That's not an issue that can necessarily be. Addressed, by, a statistical model, and in fact I think at worse the, model because, it removes some discretion, from frontline workers, limits. Their ability to correct, for, the over reporting, that happens, at the community, level ok, so that's the one where I usually start to feel people's, energy. Sliding. Because it's the most technically, complicated how, are we doing we've still got one more in us maybe two more how, are we for two more are we down here now we're so good you, guys are good sports okay. So I think my greatest fear about these systems. Is, when they go wrong. They. Really, act as a kind of empathy override. Meaning. That they allow us the coal distance, from, really. Difficult, decisions, really difficult, conversations. That we need to be having as a political, community they basically let us outsource. Some. Of the hardest decisions we have to. A computer, system that seems more neutral and objective than, we are as I, said and sort of talking about the Allegheny County system it's often incorrect, that those systems are less biased, more objective, than human, decision-makers, the, bias just gets baked, in in an invisible, way in the code but. I think there's actually a, bigger, issue here around these ethical overrides, around these empathy overrides, so, for example, the second. Story I actually talked about in the book is this system called the coordinated, entry system in, Los Angeles, and.

It, Responds, for, perfectly, understandable, reasons, to. An extraordinary. Housing. Crisis in Los Angeles so as of the last point in time count the, 59,000. Unhoused people, in Los Angeles County alone, I live, in a small city in upstate New York my city is 50,000, people my, entire city, plus, 10,000, people are homeless in LA, and. While, LA doesn't have the worst homelessness, in the United States New York City actually does what. Really. Compounds, the, problem in Los Angeles is something like 75, percent of, people who are on housed in Los Angeles have, no shelter at all meaning no access to emergency shelter they're just living outside in. Encampments. In cars. In parks. So, I absolutely, understand. The, impulse to try to make decision-making, about who gets access to limited resources, fairer. And, more objective. In the, face of this catastrophic. Human. Rights crisis, so, the system basically works by assigning. Each unhoused person, a risk score a vulnerability, score, based. On how they fill out a, very, comprehensive. And, some would say very invasive survey, with a terrible acronym, it's, known as the VI stat. Which. Is the vulnerability, index, and. Service, prioritization. Decision, assistance, tool, and. Basically. How the system works is volunteers. Or agency. Employees. Give. This survey to unhoused folks, there's, an algorithm that ranks, people based on their vulnerability. To some of the worst outcomes, of being homeless and there are very, significant. Bad outcomes, to being on house, mental. Health crisis, health crisis, community. Violence sexual, violence. Mental. Health crisis all sorts of really horrible things can happen to you when, you're on housed, and. Then on the other side, of the system the system is collecting. Information about. Available. Housing. Resources. And in the middle there's supposed to be an algorithm, that matches. People, based on their vulnerability, score to, the most appropriate available. Housing for them the, reality is there's a guy in a room and. Not actually a second algorithm that's not in the book so she. But. Often. There's sort of a ghost worker in these systems making, the technologies, look a bit smarter than they actually are, um. And, the system, actually serves, those who are very very vulnerable quite, well so the people who are a prioritize, really, high as having multiple issues. That really need immediate, intervention, are doing, pretty well through this system. Strangely. The folks who are least vulnerable, are also doing, pretty well through the system because they only require a very, small, investment of time, and resources to get back on their feet to go from being a sort, of emergency, homeless. To to keep them from going from sort of emergency, homeless to crisis homeless so. I was really interested in the 30,000, people in the middle who had been surveyed, through this tool but had never received any resources, at all from, the system people, like Gary, Boatwright, who's a, person, who I met who's living in, a grain green tent on East 6th in the.

Neighborhood, Of Los Angeles known as Skid Row, and. From, Gary's point of view the problem wasn't his comparative, vulnerability. Like how vulnerable he was compared, to the, guys living in the tent next to him it was simple math. Right there's just not enough housing. In Los Angeles for the counties 59,000. On house people so, he told me quote people, like me who are somewhat higher functioning. We're not getting housing it's, another way of kicking the can down the road in, order to house the homeless you, have to have the available, units, show, me the units otherwise. You're, just lying, and. One of the things that Gary shared with me that was really an a really interesting analysis, of the system is that he said he felt like he was being. Asked, to incriminate, himself for. A slightly, higher, lottery, number for housing, and this actually is a really good analysis, of the system because, the VI spat at in trying to establish who is most vulnerable actually. Ask some really invasive, questions. It asked for example, are you currently trading, sex for drugs or money it. Asked if there's someone. Who thinks you owe them money and asked if you've been thinking. About hurting yourself or someone else it, asks where you can be found at different times of the day and asked if they can take a picture of you. Asks. All sorts of things about HIV, status mental, health status, and. According. To federal data regulations. Some. Of this information not all of it but some of this information when it gets entered into a system called the homeless management information system. Is available. To law enforcement with. Absolutely, no oversight, at all just, based on an oral request so. This is actually not a bad. Analysis. Of the system that Gary has that it felt like he was being asked to incriminate himself in, exchange. For a slightly higher lottery number for housing in fact. About a couple, of months before the book came out Gary, was, arrested, and. Charged. With breaking the window of a public bus with. A 99-cent. Store, like plastic, broom, which. When he called me from LA County men's. Jail. He, said was quote physically, impossible. And. When. He got out if he if he chooses, he was in for about a year waiting. Trial he couldn't afford bail of course because he's on house so he awaited trial and I'm inside. And. When he got out he had sort of lost everything he lost his network, of friends and, organizations, he losses it's paperwork, and. If he chooses to interact with the VI spit dad again if you choose to take the V ice but Dad again because, it can't leave Los Angeles County of course because now he's on probation. He.

Will Actually score lower on the vi spat, because the VI speed ad counts. Or the. Coordinated, entry system counts. Being. Incarcerated, as, being housed, so. Will actually have a lower score. And, be seen as less vulnerable if he chooses to interact with the system again my. Greatest fear here, is really that we're allowing, computers. To. Make. Decisions. That are inhumanly, just difficult, to make and they, are allowing, us to escape having, the real conversations. We need to have around. Why. We have a housing crisis, that is so severe that no, county in the United States currently has enough, affordable, housing, to meet demand right, it's not just at Los Angeles it's everywhere in the country, and. I really. Fear. That by. Allowing. These tools to step in where we're afraid to have hard conversations, we're, sort of limiting. Our political vision. And we're, outsourcing, some, of the most difficult decisions we have as a human community to. Computers. How. Am I on time Amy. Right. On so I want to talk very. Briefly about. Some. New work um that, I've done cuz because. There's. One piece of the book that I often don't talk about as much which, is really about the way the digital poorhouse creates, a regime of, extraction. Meaning. Like literally, pulls, money, out of the pockets, of the people that. Come into contact with, it so one thing that was unique about poor houses in the United States is that we actually combined two, institutions, from other places, one. Was the almshouse which, was the place was sort of a charitable institution, for. Caring for the elderly. Orphans. The the. Sick and disabled, with, what was known in, England. As the workhouse which. Was an institution. For enforcing, work and forcing. Poor, people to labor was more, like a prison than. Like a homeless. Shelter and. We in the United States combine these two things into one single thing the county poorhouse and all, along through the history not only were these institutions. Used to sort of contain. And, control poor. And working-class people they, were also used, to create profit, so. In the back, in the earlier times, I was talking about sort of the 1819. Through. About the 1920s, part. Of the payment, for the person who ran the poorhouse it was called the overseer, of the poor or the superintendent, of the poor part. Of their salary. Was. Paid, by. Their, having. Access to use of the land that. The poorhouse was on here, in. Rockbridge. County it was a 500, acre farm. 231. Acres of it were cultivated, and, it was making a significant, profit every year profit, that went to the. Poor. The poor master, and. Elsewhere. Like in my own home County Rentschler County in New York, where. Our institution. Was called the Rentschler County House of Industry so it not only had a farm but it also had a quarry, where, folks. Who were incarcerated in the poorhouse were forced to work. Splitting, rocks, so. One of the things that happened when I was when I was sort of out talking about this book in the world is, I ran, into some folks in Australia, I was really lucky to be able to go to Australia and New Zealand who. Were working on a political. Campaign called, the knot my debt campaign so. There's an organization called not my debt and also the Australian unemployed, workers union who.

Told Me about a system in Australia called, Robo, debt and Robo. Debt is basically, a system where, their federal, agency. That deals, with their welfare programs, wrote, an algorithm to go back through their historical, records and to. See if they had perhaps, overpaid. People, public benefits, in the past, the. Government there, sent out, 800,000. Letters, that. Said oops we overpaid, you up to seven years ago um, anything. From you know $50, to $10,000. And, you know you have a couple of options you can pay us back now. You. Can prove that you don't owe us that money or. You can face civil or criminal penalty. And totally, a total, disbarment, from access to public resources. In the future, there's. Been a huge. Huge. Huge social movement that's risen up to, push back against, this system if you want to look on Twitter with, the hashtag not, my debt you'll see some of the great work that they're doing or. Look up the Australia unemployed workers union but. I had some great conversations with them while I was visiting and then I came home and I thought to myself hmm. Like. I wonder, if this is happening in the United States and so I spent the last seven, months sort of looking into whether this was happening in the US, and. It, turns out it is so, there are these there's been a series, of predatory, policy, changes, that have really, turbocharged. On what, I talked about in the in, the in an article I recently published in the Guardian on October 15 that. I talked about is government, zombie debt collection, in. Public services so in 49, out of 50 states across, the country. Agencies. Like human services, and unemployment. Insurance. Are. Using. New technology, to look back through old records to. Identify cases where, they believe they've overpaid, people in the past and. To send out really frightening letters, to, tens of thousands, of people a year. That. Say basically, the same thing as this Australian Records as, this these. Australian letters say, so. One. Agency, in one state Illinois Department of Human Services is sending, out an average of 23,000. Notices, a year, that. Claim that families, have been overpaid, public assistance in the past as long ago, as 1988. So, on the on your right there is dreamer Richardson, I'm she's 76 she, lives in Steger Illinois, and. She received, a letter recently, that said that they had accidentally, overpaid her $7,000. In cash assistance, in food stamps in 1988. And. If she wasn't able to pay back the balance of, what.

They Believe she owed, that. They, would the state would send her debt to the federal, treasury program. That would, offset. Meaning. Keep. Her. Federal, tax refunds, a portion. Of her Social Security disability. Benefits, they. Also have threatened to keep people Social Security benefits, they've. Even threatened. To keep the tax, refunds, of the adult children, of parents. Who supposedly, oh these, old debts the, problem, among. The problems in dreama's case is that, the debt was incorrectly, calculated. In 1988. So it was calculated they, thought that, dreama's daughter star lived, in the household at the time and they, were counting, her income, from her part-time job at Taco Bell as part of the households income but, star actually didn't live at home at. That time so, when they tried to fight it in court they, went to court and the, court said, oh the, stet the the on the, statute, of limitations, on when you can asked. To. Challenge, this debt was 90 days starting. In 1988, when we sent you that first notice so, there's nothing you can do and. So right now they're, fighting. To. Keep the federal government from keeping, dreama's. Social Security of, dreama's Social Security disability, benefits. Tim P geese over here is a great. Incredible. Man from Chicago 75. Year old guy, from the south side of Chicago. The. Department, of Human Services in, Illinois used the threat of sending, his, supposed, debt to. The. Top program to force him into a repayment plan, where. He's been paying back an, alleged, debt for. Food stamps, five dollars a month for the last 16, years and, Tim. Told me well, five dollars a month doesn't seem like a lot unless you don't have five dollars a month and then, it seems like a million dollars to you and that's, the letter that um that Tim got about his supposed debt at, the at. That at the time so, hundred, tens of thousands, at least I suspect, hundreds of thousands of families are receiving these letters right now, that. That are about debts that are as old as 30 years ago debts that are often incorrect. Debt. That they often don't remember. Incurring. And and for, which they're told the only thing you can do is prove to us that the debt is not valid, but of course with 30 no one keeps 30 year old cash receipts, for their household expenses. So that's largely that's. Largely impossible. So, I talk. In the book about the, digital poorhouse, as an institution, for diverting, people from public resources. But. I am really concerned about, this new move of, not. Just diverting, people from resources, they might get in the future. But. Trying. To collect retro, actively, benefits. That the government believes that they, were overpaid. In the past this is something that we certainly would, not tolerate on the private consumer, debt market, where they're very clear, rights, that consumers, have around, debt right, if dreama had gone bought a jet ski they. Could not do on a credit card the credit card company could not collect on her like this right, so but, the federal government can reach, so much deeper into people's pockets and doesn't. Have to follow any of the rules that protect, private. Debt. So, the. Good news is that there's been extraordinary, success, in raising these issues in Australia. Unfortunately. We haven't reached that, stage, in the United States yet and, I hope that, this new work really. Raises. Visibility. Of this really. Extraordinary, extortion. I think of some of the most vulnerable families, in. The country so, I'm about to wrap up we got we okay for five more minutes we got it oh you guys are good is it okay it's okay to say no okay. We're still good great um, so. You. Know I think it's important, to say that it doesn't take bad intentions. To reach bad impacts, with, these systems and in fact most of the folks I spoke, to who, designed, or administered, these systems were really smart really. Well-intentioned, people who genuinely cared. About the folks their agencies, serve, and. They've. Actually in many cases, done, lots, of the things that progressive, critics of algorithmic decision-making, have asked them to do they're. Largely. Transparent, about how the systems, work they've released a lot. Of information about how the systems, work they, are, keeping. The systems in public, agencies, meaning there's some kind of democratic.

Accountability About. How they work, and. They've even in some cases done, some kind of participatory, design, where. Frontline, workers, and sometimes, even impacted. Families have, had an opportunity to. Talk to designers, about how these systems work in, other, words, except. For maybe Indiana, which is a pretty bad case the, other cases I talk about in the book are really some of the best systems we have not some of the worst I think it's important to talk about that because it really raises a challenging, thought which. Is, what. If the problem with the coming age of artificial intelligence and machine learning in, social, services is not broken. Systems. Or bad, actors, but. Rather systems. That carry out that deep social programming, I talked about earlier, too. Well, that, police, and. The. Behavior, and limit access to public resources, for the poor - well, so. The designers of all the systems I talked to in. Researching. The book I did 103, interviews for this book they. All agreed on one thing that. Data. Analytics, matching algorithms, automated. Decision-making, are. Potentially. Regrettable, but they're really necessary. Systems for doing a kind of digital triage. For. Deciding, like whose need, is. Pressing. Enough that, the state should respond, right away and, who, can wait, but. One of the points I want to make in the book is that, that decision, to triage, at all is a political. Decision, and. In fact we're using a language of triage incorrectly. In these systems triage, is really only appropriate if you're. In an. Immediate, crisis, that. Has a potential, end and if, there are more resources coming if. We are in an ongoing crisis. That has no clear end and there are no more resources, coming then what you're doing is not digital triage, it's. Digital or automate, rationing. We're rationing. Services, and rationing, resources and, that, feels like a really different kind of a conversation than a conversation, about how to optimize, digital. Triage systems. I wrote. The book because I think we deserve better our. People, deserve better our communities, different deserve better families. Deserve better and I, believe that like the fundamental danger. Of the digital, poorhouse lies. In the way that it falsely, constricts. Our vision both our political vision. And. It sort of arbitrarily. Imposes. Limits. On our resources, but. The political moment that we're in right now and, I, believe justice itself, really. Demands, that we think big that we push back against. This austerity, fever, that I talked about earlier in the talk so, what do we do I want to spend a couple of minutes talking about solutions and wrap up and have, a conversation I, absolutely. Know, that. In many rooms particularly, the rooms I'm in where I'm talking to designers, and and. Computer. Scientists, and folks who make these tools that, what, people want is for me to give them like a five-point plan for building better technology. And, I wish I could give that to folks but I'm also glad I can't, because. These are actually, much bigger problems. Than. We, can. Deal with by tinkering, around the edges of technology, I. Believe, we have to do three kinds of work really. At the same time simultaneously in. Order to get to better outcomes. First, is narrative, work we have to change the story around poverty in the United States we, have this crazy story we tell ourselves here, that poverty is an aberration that, only happens, to a tiny. Percentage. Of probably, pathological. People the, reality and. I'll, appoint, people to mark ranks really fantastic, lifecycle work around. Poverty in the United States is that, 51 percent of us but we'll be below the poverty line at some point between the ages of 20 and 64, at some point in our adult lives and two-thirds. Of us will reach out for support to means-tested, public services it's straight welfare that's not Social Security that's not reduced. Price school lunches, that straight means-tested. Welfare um. That means that we're not all equally, vulnerable to, poverty that's is not true at all. If you, are a person of color if you are, someone who was born poor if you're caring for other people if you have mental health challenges, physical. Ability. Challenges, then you're more likely to be poor and it's harder to get out once you're there but, the reality is poverty, is a majority experience, in the United States not a minority, experience and, by, shifting that story I really hope we can shift the politics.

That, Says that, what, public. Service programs. First and foremost, should do is decide, who deserves help, to, shift it more towards, universal systems that, decide. That. Where we decide as a community, that, there's a line below which no, one's allowed to go for. Any reason, like no one in the United States goes. Hungry no. One in the United States lives on the sidewalk, in a tent for a decade, like, no family, in the United States is split up because the parents, can't afford a child's medication at any, point we can decide, as a community, that that is simply unacceptable. In. Other places around the world these things are I think really quickly, recognized, as what, they are which. Is human rights violations, here. We are talking about them more and more as questions, of systems engineering and, I think that should really give us some pause about, the state of our national soul about. Sort of who we are as a people in. The, meantime as, we do this really hard work this narrative and political work of shifting, how we talk about poverty and how we respond, to it the, technology is not going to just sort of sit twiddling its robotic thumbs and. So we also have to figure out how to design technology, that does less harm in. The now and I think one of the ways forward around this is by, building, technology. With all of our values. In mind from. The beginning we, often, think that we're reaching fairness. And justice if, we, design technology. To be absolutely. Neutral to. Just. Apply. Rules, the, same way every, time no matter the context. But, the reality, is that's. Like building a car with. No gears, and then, putting it in a really bumpy twisty. Turny hilly, landscape. Say, like San, Francisco and, pushing. The car off and then being somehow shocked, when it like bursts, into a ball the fire at. The bottom of Telegraph, Hill we, need to be building equity gears. Into, our technology, from the beginning and that, means paying attention to efficiency, efficacy, and cost savings, of course but. It also means designing, with our other core values, things like self-determination. Dignity. Fairness. Due. Process, and equity, so. If we're to have a more just future, we, have to build it on purpose. And not think it will happen by accident, brick. By brick byte, by byte in every, system we build and if, we outsource, our moral responsibility, to care for each other to computers, we, really have no one but ourselves to blame when. These systems supercharge, discrimination. And automate. Austerity. I really. Appreciate, your time your patience, I'm eager to talk to you about your. Questions if you have them thanks, so much. Let's. Give folks a moment to sneak away snakesnake. And. Then I think we have some mics. If. People have questions. We. Ask you to use the mic so the nice people on the interwebs. Can hear you. Thank. You so much that was brilliant and I, love, your. Visual. Thank, You Shane yeah, a wonderful. Artist named oh. I. Just forgot her last name, I mean her first name her last name is Vulcans vasconcelos, and oh wait, it's on the slides. I'm. So I'm sorry Elvia. She. Did. My slides for me it was an incredible, incredible experience. Because and I wish I'd done it before the book was published because, she forced me to think in visual metaphors, about. The key ideas of my book and I was like oh everybody. Should do this it's so clarifying. So, yes, she's wonderful she's also available find. Her on on, Twitter yeah. Lvova it's data visualization. And translation, of your ideas, and that. Depiction. Was it, was just really lovely, thank you but um that'll mean thank you for Elvia. But. Um a lot. Of, it. Seemed like a common theme you brought us, back to were, these ideas of creating floors of universal, human, rights and that that would be an anchor to. Then ground, us in more of a human, to human process. In the, way that we attack these very complex, problems, but, it seems like for almost, a century now, with the increased, bureaucratization. Of the. Processes, of, how. We handle these types of problems then, led to more. Of a technocracy. And, then, now, into. The, quagmire that, you're describing. Is. There a way to even. If we have some, type of universal.

Human Rights standards imposed. Which. I think would be very very difficult in the United States and. I, I don't know whether or not we could even for, example amend the Constitution, in order to achieve some of those goals that you have, legally. But because, the infrastructure, for how we, deliver. Some, of these services. Is, so. Embedded, within this bureaucratization. And. Because. The bureaucratization, has, become, so technically, and, technologically. Dependent. You. Know would there be a, way that. We would be able to get back to you those universal, floors or would we just find new ways, of technologically. And algorithmically. Automating. You, know decision, making even if we had the pretend, fours I'm. Concerned, that you, know what I mean that that we just wouldn't even be able to get there yeah so, I often, I want to take you all the way back to the history briefly I, so. One of the things that was really interesting about writing this book is when I first started, it so I first got interested in a system in New York State called the welfare management system WMS, and I, live really close to the State Archives and I'm a little, bit of a geek in that in the way my, deep abiding, love of archives and so I was like I want to know more about I want to find the technical documents for this thing and so go to the State Archives and, I'm, like I wonder when it was designed right like so in 1996, the policy, change we had to automate eligibility. Systems across country like okay I'm gonna look in the 90s no it was already there in the 90s I was like oh well then it must have happened in the 80s when the technology became available back. In the archives nope already there in the 80s I was like oh that's, weird I wonder how back this far far back this goes and I kept going back through the archives and I, found that these tools actually started, to be built in a really interesting moment in our history which is like 1967. 68 and 69 and what's. Really important, about understanding. Why that matters why that moment matters is because it wasn't driven by the availability of the technology, it wasn't, driven by new policy, it was driven by the problem. Of the, welfare rights movement, that was having this extraordinary, string. Of successes. Fighting. Back against, discriminatory, eligibility. Laws, had kept the. Majority, of folks who had been kept from public, services. Between 1935, and around 1970. Where women of color so had had just just. Explicitly discriminated. Against, women. Of color but also single. Single. Moms sexual.

Minorities, Like folks. Who weren't seen as deserving um so. The welfare rights movement is turning, like overturning, these laws left and right at the same moment there's a backlash, against, the civil rights movement against the welfare rights movement, and a recession, so, state, lawmakers, like, a really, stuck between, the. Rock of like you can't legally discriminate. Anymore and the, hard place of but, the non. Public. Assistance, using. Population. Is not feeling good about these programs right now and that's. The moment that, you see these tools, start, to go in into. Operation. And I think what's really important in New York State I'm not sure it's true in every state but in my own state. The. Moment, these tools came online was, like within months, of a, moment where 8,000. Frontline, caseworkers, walked, off their jobs in, a strike not for their own employment, contracts, but, to lower barriers to assistance, for their clients, right, so I think like the incredibly, dangerous moment. That the state is reacting to by inventing, these technological tools is the, incredibly, dangerous moment, when caseworkers, and clients, saw themselves on the same side and so. For me as someone is who's, an activist, and an organizer, that. Feels like the work it's like well how do we get back to that, moment, where we saw each other as being on this may that brief moment that we saw each others being on the same side and for me that's about building movements, it's, about building movements, led by people who are most impacted by these changes, and. And by supporting, those movements I really I honestly think, that's the, really the only way we're, gonna get to this change because these systems don't change without a fire being lit under them, they're. Just too politically. It's too politically popular to pardon. Me, upon the poor I'm right, and I'm not talking about a single party all. The parties enjoy. Scapegoating. Poor working-class people and. So I really, think a lot of this work is movement work and. I think the good news is it's happened before it can happen again I think, we lose sight we, like we limit, our political imaginary, when we forget the history of these tools and we think like oh it's always been this way I mean. I talked to caseworkers, who as, late as the 1980s, they just had a drawer a cache like. You would walk in somebody was having a like a really, terrible crisis, and he would just like reach in and give them a handful of cash right. And I don't know that that's the best way to do it right there's all sorts of possible problems with corruption and and not, tracking, where money is going and things like that but, just think about how different. That. How. Much we trusted, caseworkers. At that moment and how we don't now and. I think many of these tools are aimed at this, idea that caseworkers, are incompetent are corrupt and are in collusion with, clients. To defraud the government and, I think, there's. A lot of room to build there it's very hard work I did I did, that work politically, as, an organizer trying. To build links, between caseworkers, and recipients, and it is very hard work but I think it is like it's hard because it is regime, changing. Paradigm. Changing work that that works yeah. So I really think that's where the solution, lies but. There are a lot of people doing great work in doing technical, tools that come from other values orientations. Right from, pushing back on policy, like all of that's important work just, like where I aligned, with the work is around building that strength of the people who are most affected to. To change the systems, that constrain. Their lives yeah. Thanks. My question yeah. Right. There. First. I just wanted to thank. You for giving this presentation on, your work it was really insightful and some of the problems in these systems, so, my question deals with the with. Your discussion on how these systems outsource, moral responsibility, in the decision-making, process to machines, from institutions, and policy, makers so my, question deals with if we, can imagine a system, where. These type of automated. Systems are producing. Results that are in line with what we would consider our moral, and justice based goals and inclinations that, the reasons we've created them in the first place where. The outcomes are not racially, biased they're, not enforcing. Problematic, narratives, and so on and so forth, do you still find there to be an intrinsic problem, with, separating, and outsourcing, our moral and ethical responsibility to an algorithm, assuming, that it's producing, results that are in line with our values yeah, that's a really good question Wow Europe, you're a philosophy, major aren't you I.

Can. Tell. That's. A great question so, and, the answer for me is yes and. The reason is so it's really interesting I'll, tell a quick story as, a way of illustration. So. Because. I've done the work on the Child Protective Services. Agencies. Predictive, analytics and Child Protective Services I've been in a lot of rooms where. Like. In. New, York City it's called the ACS the administration, for Children Services are, like. Responding. To families, around, their. Use of predictive analytics and so I was at an event in New York City about a year ago with. Some folks from ACS, and also some organizers. Folks. Who are parents, in the, child protective service system, not. Super fond of the agency, as you imagine, it's a really try it's a tough relationship no, matter how well you're doing it it's a tough relationship. And. Just. The. Most fascinating, thing happened, which is the the official. Who was there from the, children, youth Family Services. Was. Getting a lot of pushback. From the audience, around issues, of racial disproportionality and. This is there's huge issues around racial disproportionality in, foster care in new york city and. He. Got. A little defensive um. And. At some point he just kind of snapped back and he said well I guess you guys will be happy because. Since, we're using the predictive analytics, way more white kids are getting taken and. The. Room, went just like I see silent, and one of the moms african-american, mom was like you. Know that's not what we want right like we don't want to make equity by, making, more people suffer, like what we've gone through like, that's not what we mean when we say equity. And, so. For. Me I think we use these limited, ideas, of fairness, in these systems that. Keep us from addressing. These harder, bigger questions, and then, we lose sight of the goal and this is the direct answer to your question which is the goal is human development the goal is for us to have to have these conversations, because. We learn from them because we get better right. So if you talk about say. Algorithms. That. Control. That. That constrained, judge decision, judges decision making because, you, know many judges have records of making racially discriminatory, sentencing. Decisions, right, so even if you get a perfect algorithm. That. That. Evens out the racial, disproportionality. Eius. Or whatever, you. Still leave, a racist, judge on the bench right and the point is for, us to be able to have that conversation that, says like, what's going on with your decision-making like. I have, that big conversation. Of why do we have these, racially, discriminatory, effects. In sentencing. Not, like how do we tweak the results, so the numbers look better right so, that's my fear that we're losing track. Of the, real issue which is like how do we all, morally. Develop, as a politically. As a political, community how, to really really face hard, questions, around, racial discrimination. Around class discrimination around gender discrimination, in. Ways, that, let. Us all grow. And recover. From trauma and, become, a better community. I'm afraid, right, now that these tools are often used for exactly the other to. Go in exactly the other direction which is to say like. Oh my god you poor homeless, service. Worker you see a hundred people a week and you can only give two of them resources, you shouldn't have to make that decision that's too hard it's true should not land just on that person that is too hard for one individual, to shoulder it, is a decision we all have, to take responsibility for no one should be put in that position because. We shouldn't be making decisions of, who among those hundred people get, resources like everyone, deserves housing, housing, is a basic human right period.

And. I have a an activist. Who is a great hero of my name Cheri honkala from the poor people's economic Human, Rights Campaign and she says oh we already had an algorithm for who deserves housing she's like we call it the belly button algorithm. Right, like got a belly button you deserve how's that hey I've. Since been corrected. That all placental mammals have belly buttons so it's not actually as good as it sounds but I still, really like it so I still use it so. Sometimes I think we're just using the math to escape the, really hard, commitments. To doing better by ourselves our, families our communities yeah. Really caring for each other Thanks. That question. Oh. Wait. Let more there's one more don't clap yet'. Don't. Think you can hide. Hi. Um so, if housing, is a human right how, do we work. To ensure that there i

2019-11-19