Julia Koerner Models and Models Alberini Lecture

Most important this speaker series is supported through an endowment by the Carlos and Andrea Alberini Family Foundation Which brings renowned innovators and thinkers thinkers in design to campus to inspire students and encourage encourage community engagement and learning. It would be hard to overstate to the Alberini family how meaningful this speaker series is to the intellectual life of our department and its students Thank you so much. It's my honor honor to invite the Chancellor of UC Davis Gary S. May to open this afternoon's event. Chancellor May earned earned his master's and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineerin computer science at UC Berkeley and is a member of the National Academy of Engineering and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences His vision as UC Davis's seventh Chancellor is to lead the university to new heights in academic excellence, inclusion, public service and upward mobility for students from all backgrounds. Please welcome Chancellor Chancellor Gary S May.

And I'd like to introduce our speaker this afternoon -- for this afternoon, Professor Julia Koerner, a highly acclaimed Austrian designer and founder of JK Design Her work intersects with architecture, product and fashion design, and she is internationally recognized for digital design in 3-D printing. And I should add, I've just been talking to Julia and she really has gone the extra mile for us. She is joining us today from Jordan. I think it's the early hours of the morning Julia received master's degrees in architecture from the University of Applied Arts in Vi and the Architectural Associatio in London.

She previously held academic appointments at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, at Lund university in Sweden and at the architectural association visiting schools in France and Jordan. She is a faculty member in the architecture and urban design department at UCLA. Where she is the director of summer programs. Her designs have been featured in the National Geographic magazine, Vice, Wired, and the New York Times, among other publications In 2019, Archinect named Julia Architecture's Queen of 3-D fabrication. Her work has been exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the High Museum in Atlanda the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Palais des Beaux‐Arts in Bru You know, we couldn't be hosting a more inspiring speaker as we look forward to returning to campus and making things together again.

While we've been away, the Depar Design has been transformed with the completion of a new maker space, developed with the spectacularly generous support of of Giacomo Marini and of the Marini Foundation. The maker space includes an open lab for project critiques, a metal shop, a wood shop prototyping classroom, an an MFA students graduate student and undergraduate students in industrial design wearable tech and prototyping classes have already been 3-D printing, and laser cutting this year thanks to the work of our TAs, design staff and above and beyond supervision by some of my colleagues. And I think that's my kind of entrée to prepare to be transported now by Julia's work, and to imagine the futures made possible through technological change in design. Today's lecture will be followed by a Q and A, to which we warmly invite you by writing questions in the box on Zoom during and after Julia's talk, so if you look, there is actually a Q&A bo I think maybe the chat is open as well, but there's a Q&A box, if you want to pop questions in there, and Julia will hopefully be able to answer them after the talk.

So with that, I'm going to turn proceedings over to Julia. Thank you, Julia. >> JULIA KOERNER: Thank you, Simon, for the great introduction. I'm going to share my screen. Thank you so much for the invitation for this great lecture, and I'm very happy to join as Simon mentioned from Jordan.

As the date came closer, I was moving every time further away, it seemed to me, first Austria and now in Jordan and I look forward to returning to Los Angeles quite soon. I'm very happy to speak at UC Davis today, and I would like to introduce myself, so I'm Julia Koerner, and I'm the founder and director of JK Design in Austria and Salzburg and the cofounder of JK LA LLC with my partner and husband (indescernible) and I'm an adjunct assistant professor at UCLA in the architecture and urban design department where I'm also the director of the summer programs My work bridges between multiple scales. I'm trained as an architect and I work between architectural installations, product design, and fashion design. Most recently, also more and more in the costume design industry.

Today's talk is called "Models and Models" And I want to talk more about inspirational personalities, which kind of worked with me along my path, and inspiring female people who have inspired me along my way. First of all, I'm really inspired by Charles and Ray Eames and their kind of and their kind of philosophy behind their practice inspired by nature and practicing in architecture. While my studies of the University of Applied Arts in Vienna where I was studying with Greg Lynn, I I was also fortunate to be in next to the studio, which was taught by Zaha Hadid, who one of the most inspiring architects I ever met in my life and who really has led a great path for young architects like me.

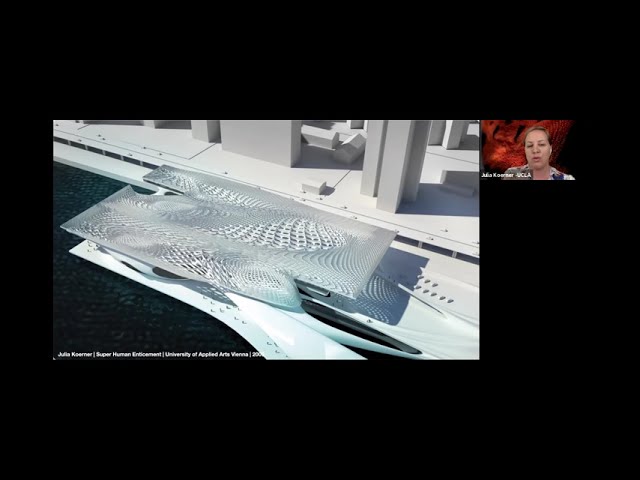

to have an aspirational model to kind of follow along. Coco Chanel has been always a huge inspiration for me I was always in between fashion and architecture, interested in both paths. Little did I know that I studied architecture in order to later on to return to work in the fashion industry and to even have the opportunity to work with high en fashion brands in Paris and to kind of cross bridge the disciplines between architecture, fashion, product design Models such as Amy Mullins who have been ground breaking in their paradigm change of looking at how humans are perceived with disabilities and how the kind of super human enticement can be embraced. I made this my thesis at the University of Applied Arts The human anatomy and its body, and the space surrounding it was something I was very interested from early on.

And Greg Lynn, who was my professor in Vienna who brought me to UCLA, who I was teaching together together with at the super studio, which is a post-professional degree. When I first time saw the Embryological House Switzerland in an exhibition, I knew I really wanted to study with him, and he kind of opened a lot of opportunities for me. And I think these kind of role models are one part of my experience, which led me to where I am today but on the other hand also models can be seen as like physical models models as models in the fashion world figures which represent the fashion items which I design, and also in in architecture disciplines.

In my design I looked a lot at the kind of convergence between nature and the implementation of organic design language. And I'm inspired by what you can find in the various different body parts inside and outside and the human anatomy it's kind of embedded within an esthetical language I developed over the past 15 years. Here for example you can see a case for an artificial knee This was a case study which I did as a student, but I show this because it kind of shows my early interest in the kind of relationship between muscles and bones and how this kind of organic formations and morphologies have led itself into the development later on designing architectural spaces or enticing products In my thesis inspired by Amy Mullins I designed the biometric research center in Manhattan where I took the idea of taking the kind of development of prosthetics outside of the hospital of a basement up into a showroom and kind of showing what opportunities and ppossibilities you can have and how it can kind implement super human enticement into this kind of paradigm change. For anyone who doesn't know who Amy Mullins is, she was born as an amputee, and she kind of modeled for a lot of different fashion brands in the early 90s where she -- in 2000, where she kind of had the ability to be one of the tallest models on the cat walks, because she had made herself shoes and fashion items which kind of enticed her and she had abilities which others didn't have, and I I thought this was a really inspiring opportunity, and especially with 3-D printing and emerging technologies, I look with how architecture you can embrace such a place and design a futuristic place where this can occur. occur. In architecture we use 3-D printing to create physical models, so what we can see here is a small scale powder printed physical model, and at an early time, at the (name) around 2005, the school had the first 3-D printer and I I thought this was a really exciting moment because I could kind of visualize not only on the computer but I could make my ideas tangible and I was very interested in this output back and forth between the digital and the physical environment, and so I implemented these kind of learning experiences and often errors which I received in those those physical models models into my design processes.

While I was a student already I got the opportunity to work with Ross Lovegrove, an industrial designer based in London, and so I started started to kind of be between London and Vienna Vienna, go back and forth, and I worked with him on many , many product design projects where we looked into how can we bring the architectural design processes and parametric design, generative design, modeling techniques into product design. This was what we we designed (indiscernible) which was supposed to reflect the light in different nuances and directions but it was not only an asthetica approach, it was also how can we utilize inexpensive fabrication techniques such as ferma-forming in order to create large scale lightning sculptures but also how can we utilize 3-D printing and injection molding in order to produce a larger series of elements for chandelier, for example. another light design I developed with Ross is the new nature light, also for Artemide, and in this case we looked into how can we optimize an injection molding process, because injection injection molding is quite expensive. You have to invest in one mold. So we had repetition in the mass production is quite recognizable.

And in this light, we looked at how to make a column out of 16 parts while there is no repetition essentially visible, and it doesn't look anymore like a repetition of 16 elements and we used 3-D printing in this as a method of understanding how we can make one single mold for one part which is then flipped around, mirrored and kind of implemented into the whole light. And we also looked into the various different shading principles and lightning to the inside of the core of the light, and please keep this product in mind because I'm going to come back to it at the end of my talk later on. So remember this project. Around 2010 I got the opportunity to do the MAK Center scholarship it's from the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna and an international scholarship to go for six months to L.A.

and live in one of Rudolph Schindler's case study houses in the MAK apartments in this case where for six months, I researched the bio diversity of California. It was my first time in California, and I I went to all the different national parks and took the opportunity to create more than 2,000 photographs, and a lot of different videos of the various different bio diversities its and all the patterns which you can find in nature. And I realized that I'm not only interested in the aesthetic and the kind of bio mimicry of those forms and shapes shapes, I more and more was interested in interested in the mathematical underlying underlying logic of those, so I really realized I wanted to understand how can I create such structures and formations with the computer. And so And so I decided to go back to London and do another master degree in architecture, especially in emergent technologies and design at the AA. That's also around the time I started to utilize 3-D scanning and I started with laser scanning and then later on with CT scanning, computer tomography tomography, where I looked into, for example, corals corals and how their internal philosophy levels can be captured with those scanning techniques. So not only the exterior can be scanned but also the interior and the reason I was interested in that was because I really wanted to understand how can this underlying beauty, what we find in natural formations can be implemented into design processes And so understanding those mathematical logics led me to not only be able to learn how to 3-D model such systems, but also how to make those tangible, and so I continued with my 3-D printing processes that I learned earlier at the (name) and had the chance to grow at (name) but I also looked into scripting efforts and how to write code this was a collaborative project with Marie Boltenstern and Kais Al-Rawi where we started to look how we can set up a simple script, not simple, actually a quite complex script, but which can read certain parameters and then change according to those inputs and parameters. So in this case how can you

change the porosity over a certain surface, so that it so that it can adapt to different levels of density and openings and apertures and so forth. And you no longer have to repetitively model everything physically but you kind of generatively develop a process where you automate that. We then implemented that that in various different projects. This was a façade prototype for the Acadia Conference in Canada in 2013 where we were finalists for a competition called TexFab and we plasma capped and fabricated the façade prototype robotically and then it was was very labor intensive because it had a lot of screws in it It took a lot of time to put it all together.

As we then developed this kind of similar complexity project further we got -- we won a competition for -- which was done through the AIA Los Angeles, and it was an exhibition designed for the architecture and design museum in Los Angeles. It was supposed to host the 32 best student projects, exhibited for 32 best student projects of California in architecture, and so we really wanted to kind of move away from this labor intensive screws and bolts and we developed the CNC fabricated structure, which didn't have any adhesive and screws in there, so it was was a push and (indiscernible) system which had numbers at each of these drawings, and was able to be put together and taken apart. The CNC machine out of the material called Sintra and expanded expanded PVC, and we kind of had a limitation in the budget, and so it took us a while to find somebody somebody -- a sponsor, who was able actually was able to actually fabricate all of those panels panels and it was (indiscernible) fabricated who used the machines Boeing airplane windows and they said at the beginning, 'yes, yes, sure ...

... we can fabricate everything,' when they realized how many bits and pieces and panels we had, we kind of challenged challenged their technology on every end, and that is something which is really core to any project I really do. I kind of naturally always push the boundaries of what can be done with it, and it's also something something which inspires me and motivates me how how we can kind of push boundaries of existing methods and techniques. Because it's a project which can be disassembled and reassembled, we decided to exhibit this installation also in Jordan at the Amman Design Week in 2017. You can see here in the front, my partner and the queen of Jordan, who is is kind of explaining the project, but the most fascinating thing is that the entire structure fits into a 2 by 2 by 2 crate and can be shipped and placed at other locations, and so this kind of idea of reusing installations and kind of thinking about the after life of such installations is something which I really think is important as we -- as designers that we kind of think about what the purpose of these designs are in the future, and how we can reuse them or deploy them in other ways and methods. That was not only time that we participated in the Amman Design Week It's a kind of a great platform where young designers architects and artists can show their work, and we did something something in 2019 as well where we looked looked at the kind of column capitals of Petra, Petra is this carved city, Nabatean city in Jordan, where you can see here in the images, the columns have been eroded over hundreds of years, and this time of morphologies are still recognizable in the stone, and kind of next to each other, you can see columns which have not been eroded and then areas where it's totally eroded and you can see where nature takes over over time. We used that as an inspiration to create a grid 25 column capitals and the project was called "Column and Crowns."

And this idea came also because just shortly after the costume design for Black Panther where we looked a lot lot into the design of crowns and we realized that there are similarities between the crowns and the capitals of the columns, and so we kind of investigated that in a kind of formal approach that was serious We took this research even further and developed over the last year two public art sculptures in Santa Monica. They are entirely 3-D printed in our own studio printers. The reason I'm mentioned this is because at the beginning when we got the opportunity to design those public art sculptures, we thought of an entirely different fabrication process. We thought we would CNC machine them, and the reason for that was because we simply didn't have enough best of my enough budget to outsource the 3-D printing to becasue 3-D printing is still a very expensive technology. And then the pandemic started last spring and we kind of were forced, because all the shops shops, fabrication shops closed, we didn't have the opportunity anymore to kind of CNC it, and so we said that we still need to kind of realize those objects and then my partner and I, we started to investigate how quickly actually we could we actually print those on our own printers and so we figured out the method that we could actually print it without any support materials, so it's extremely lightweight, what you see is three millimeters thickness of filament being made up. You can see on the left a full print of almost 80 percent. I put this in because someone

someone might ask how long does something like this take. So this is about a quarter of one of those columns You can see here it has 22 hours left. It already printed printed 130 hours. So it actually actually took us around two months to print both of those columns. Some of those prints took

five days, and there were also errors in there, so sometimes I would would come to the studio after five days and I would see like the entire print was not working. It was a learning process, but a really kind of interesting one. And I think especially for the pandemic, we look for and more about in house, 3-D printing and one of the project, which was a result of that was the tutu which I designed for the Bulthaup Ballet for the (name) in Beverly Hills. It's a fashion item

item which we are currently working on with the performance artist also from UCLA, and she will be wearing it and kind of make a performance in this tutu and we are producing a video right now on that. currently working on with the performance artist also from UCLA, and she will be wearing it and kind of make a performance in this tutu and we are producing a video right now on that. Furthermore -- (music) I designed an award design trophy where I looked into plant based materials, so this is a new technology which we are looking looking at where we can 3-D print with materials materials which are made out of corn, and we are looking at this because I have a desire to kind of really push the 3-D printing further with not only bio degradable materials but also with materials which are use ing ing resources so this plant based materials are really fascinating because they are kind of getting away from other materials I have 3-D printed in the past with. And this is quite powerful, this technology, and this is

a very recent project I wanted to share with you today. Another very current project I'm working on with Solaris, a community start-up in Scandinavia, they have developed a process where they are recycling ocean waste plastic which they are recycling in Thailand and they are putting them into filament. This is an ongoing project. We're looking into how you can utilize the printing material for a design of the light project. I cannot show more at the moment, but this is something which is ongoing in the studio right now. During the pandemic, I also started to look more into local collaborations and so I did a very interesting project with a glass blowing artist, her name is Austin Fields, and the project was initiated by the as you Austin (name) in San Francisco, where they kind of looked for collaborations between Austrian artists and U.S.-based artists to kind of support

to kind of support them throughout the early stages of the spring 2020 of the pandemic pandemic. So we looked into kind of a work process, a (indiscernible) work process, where I would would design 3-D print ed molds which Austin would take and make plaster molds of, and she would blow glass on top of those 3-D printed objects. And this was a really great project, because it was the first time that I actually worked worked with an artist who was in the same city as I, but but we couldn't meet because of the virtual environment. And we tried to really see how could we do something something physical, something tangible, which was not only based based on virtual environment, and we never actually met, but we kind of brought these two materials of the glass and the 3-D printing together and created a series of 10, 15 objects throughout this project. In the next part of my lecture I want to talk more about cross disciplinary design processes and how recent innovation innovations in 3-D printing materials, such such as laser sintering, and stereo lithography technology have revolutioned revolutioned the cross disciplinary work of design architects. So around I would say ten years ago, there was a really interesting time right when I was at (name) I started working with 3-D printing companies, but very well connected with the various different technologies that were out there at the time, and so I looked into the micro scale of what you can do with those technologies, because because obviously it was an early stage, so you couldn't get 3-D print on a architectural architectural scale and I thought the human body was an immediate scale where you could at that kind of resolution, print very high end printers, and there was one particular project where I looked into the deep deep sea deep sea sponge (indiscernible) scripted into it so the dress would essentially look like it's growing around the human body.

body. It also had bio degradable degradable elements in there, which had a (indiscernible) pigment, so it would change from black to white, depending on the temperature of the human, and so the dress was meant to kind of showcase the mood of the wearer or showcase its expression and temperature change. You can see the elements elements here, and I think I have a video which kind of showcases showcases the process. (Video playing.)

>> Printing is transforming the fashion industry, revolutionizing the materials available and the design process. I've created a dress that reflects the mood of its wearer, made of a fabric made from a fabric that responds to temperature and touch, making the garment completely personalized to the individual. I was inspired by the natural world, especially and how organic fibers react to their environments. So my process begins by 3-D 3-D scanning living organisms—in this case a sea sponge—to understand its structural makeup and properties. I then used this a starting point to design and craft the garment. Scanning the wearer creates a 3-D model of their body giving me a basis to design the different structural properties Thickness, flexibility, rigidity of each part of the dress.

Next I incorporated the responsive materials that helped dress respond to light and temperature. With these advances in technology, it's becoming easier to imagine a future where clothing is completely personalized to the individual. Not just in how it looks, but also how it responds to your physiology physiology and environment. (End of video.) >> JULIA KOERNER: So similarly in this project where I was inspired by the deep sea sponge— a lot of my work, I'm inspired by natural elements such as kelp, for example. So one day I was walking in Malibu Malibu and I found this really beautiful dried kelp elements, which were frozen in their kind of liquid organic shape, and I took them home and I 3-D printed them, and I I kind of used those as a digital mold to model over them and to kind of generate morphologies and then I developed this 3-D printed jacket which was a collaboration of stratuses and it was one of my first ready to wear collections in 2015. And we worked with

a polyjet technology which utilizes a flatbed where you can print on, and what you can see also here, there was was still a lot of support material in what we used in this printing process obviously that creates a lot of waste material and since additive manufacturing is essentially a process where you only need to use that material with really you want to use in the product, since I would say in the last six years, I have more and more focused on how can you design without using any support materials, so you literally only use that material, what you want to have in your design, and I I have more visuals for that later. That was the sporified collection. I organized the photo shoot with an Austrian photographer at the James Goldstein house. I knew James from my architecture students where I took them several times to the John Lautner house and gave tours there, and so I reached out to him and said wouldn't be it amazing to shoot the first first 3-D printed ready to wear collection at this house and he said yes, and it was really exciting to get this opportunity to do it there, and it was later on published in SCHÖN magazine as an editorial and so at part of this sporified collection it was also the hymenium jacket. That one was in from the underside of the portobello mushroom. And I looked at these kind of (?) and undulating surfaces and developed this flexible jacket. This is a recurring pattern which has been part of several different designs up until today and I kind of turn back to this pattern a lot in a lot of my projects, even up to until today.

Also here you can see the printing process. You can see the white material essentially was used as a supporting structure. This This was one of the first 3-D prints I did with this technology Meanwhile I'm going to show you in the (?) jacket, I have created designs which don't need those kind of support materials anymore. In the Iceland collection around 2017, I thought it was my desire to kind of make less of jackets and larger garments but make it more accessible and look at more smaller scale accessories and handbags and necklaces so I started to design smaller scale pieces, often for example like the one on the right, you can see the dimensions and the cuts were inspired by the bounding box of the 3-D print, rather than essentially a cutting pattern from from a kind of pattern making perspective. So the boundary of the 3-D printer would kind of determine how large I could make a garment, and I also started to combine it with with other fabrics and stitched it on traditional fabrics and combine it with buttons and support, to kind of look into the combination of traditional craftsmanship and innovative model technologies. I took the Hymenium pattern and developed one of the first Hymenium bags.

This one was printed in house on our own printer, with the biodegradeable FDM printing process, biodegradeable PLA material, and in the meanwhile, we have developed this handbag handbag further, and we will launch it soon as a kind of new brand brand, not the new brand, a new product product, which is printed also with the plant based material. In 2019, I had the chance to exhibit and showcase some of the Iceland Iceland collection pieces which were acquired by Google and they showed it at their IO conference with a new AI app. So you can see on the bottom, for example, an image on the left, you see the read model with the handbag and necklace. On the right you can see the kind of augmented reality filter showing the virtual model next to it, and it kind of came in handy because my designs were already existing as three-dimensional files, so this was a great opportunity to kind of show the work in a different framework. I want to talk a little bit more about recent developments developments in the 3-D printing as what you will see is that in the the early stages, a lot of the designs were rather rigid and less flexible.

In 2019 I got the opportunity to collaborate with STRATASYS again on this Chro Morpho collection which was 3-D printing directly on fabric for the first time. They developed developed the technology which is not yet commercially available. But they kind of invited me as a designer to test their technology in an early stage, and so I developed this jacket which was inspired by the Madagascar Sunset butterfly and I took microscopic images of the butterfly and then turned those pixels from these little Setae— the hairs on the butterfly wing into an algorithm which can be translating then the image into a geometry. And so what you can see here is directly 3-D printed on denim.

And it's a quite simple geometry It's purely just an extrusion of little sticks, but because it's printed directly on the flexible surface underneath, it kind of makes really amazing movements, and shows this kind of animal-like vision. denim. It's a quite simple geometry. It's sticks, but because it's printed on the flexible surface underneath, it kind of makes really amazing (Music.) (Video playing.) (End of video.) >> JULIA KOERNER: So moving on from this kind of of first experiment with the Setae jacket, jacket, by the way, the Setae jacket was also exhibited in the designs for different futures exhibition in Philadelphia Museum of Art and most recently in the Walker Art Center, and it was a really amazing exhibition, it's unfortunate it's over, but it showcased a lot of really innovative new kind of projects. Maybe some of you have been and seen it. But I developed this kind of technique with the 3-D printing on the fabric further in a a nine months research, which was funded by the Horizon 2020 European Grant and it was a research in Austria where I collaborated with a variety of different technology partners.

One of them Stratasys, (name), and the University of (Minsk?), and in this research I wanted to see, with the Setae jacket, I still based the kind of idea on traditional cutting pattern, I thought, well, if I'm actually 3-D printing the the geometry and the pattern on it, couldn't I also 3-D print fasteners on to the fabric? So I did a lot of research on various different fabrics of what I can print on. This is just a small section I tested at least 50 to a hundred different fabrics. They all worked really well, surprisingly, and I also tested different geometries, and so I came up with this idea that one could do a 3-D scan— there are 3-D body scanners which can already scan your body in less than 30 seconds, something I didn't know about and was really fascinating for me to explore, so I did a lot of 3-D scans of mannequins and models. I developed three-dimensionally a cutting pattern which was based on the human anatomy, which moves away from traditional cutting methods. And I looked into how can you optimize those so you can optimize the digital process, meaning you have a 3-D body scan, and then it automatically adapts the outlines of the cutting pattern, so that's what you see in the upper left graphic here, and then essentially the 3-D file adapts to the various different body shapes shapes, so that say, humans humans don't always have symmetrical bodies, maybe sometimes we have one side larger, one arm longer, so obviously nothing is perfect, and so essentially the shape and design of the garment can adapt to your different dimensions, and also the fact we essentially had the idea that as you are changing your body over time, sometimes you're thinner, sometimes you gain some weight, would be able to adjust your garment depending on how you want a to wear it, if you want to wear it larger or smaller and so on. And essentially eliminating those standard sizes, how we buy and consume wearables today, which come in specific sizes but maybe some of us are in between sizes or we have different sizes with different brands so the integration of the 3-D body scan would essentially eliminate that step and you could have a totally customized garment.

The idea also was to kind of of -- here you can see a little bit how this is kind of -- fit to the body and would kind of adjusted based on your 3-D scan, but the idea was also how can you utilize the 3-D print for local production, and on demand production. So you no longer have to kind of go to a store, buy a thing or you order it online and it's being produced produced on the other side of the world and being shipped to your location, and then you don't like it, you're going to ship it back, there's so much carbon footprint in the fashion industry that I see really an opportunity with the 3-D printing that you can have an impact of change, because as long as we have the printing machine locally locally, we can produce locally and on demand. That is one of the reasons I focus more and more on in on in house production in order to eliminate the outsourcing as well. So the last part of my presentation focuses on many of the collaborations of what I did, and I I want to show a little bit more how much this collaboration and co-production within the fashion industry and costume industry is disrupting traditional craftsmanship and empowering innovation by utilizing emergent technologies such as additive manufacturing.

And one of the collaborations I did for example with Marina Hoermanseder, an Austrian designer designer for the Berlin fashion week. It was looking at the traditional smoking technique. It's a stitching technique where we looked into how can we translate traditional stitching patterns patterns into kind of hard shell design. Obviously I am also — I'm well-known for my collaborations with Iris Van Herpen, I have collaborated with her on three collections, three dresses, and one of them was 2012. One of the first ever 3-D printed dresses,

was the hybrid (name) dress. In 2013, the first flexible 3-D dress, which was the voltage dress, and in 2014, the biopiracy dress. I'm going to walk you through a little bit on those collaborations, and this was printed in a selective laser—in a stereo lithography printing process, one of the largest printing processes where you can imagine the liquid resin and it is struck by a UV light, similar to the plant based award trophy what I showed you earlier. However this one was printed printed out of regular resin, and this is is the natural color so it kind of curves over time and gets this honey color through the UV light. This one was a rather rigid 3-D so you can see it doesn't flow yet so much with the body. It's more like a rigid corset

And this was showcased at the Paris haute couture shows in 2012. and the printing process took seven days for each side. There was a front and back piece and in 2012, this was really pushing any boundaries of what can be done computationally. These are some of the renderings what you can see here, and they are not published anywhere. So that's kind of

a unique way to see how complex the geometry is Actually I'm wrong. They are published in AV magazine, I wrote an article where they are showcased. On the right you can see here the front and back and the hinges is even 3-D printed and I kind of always look at it as an architect kind of in various different perspectives, and it's beautiful because in the three-dimensional space, you can zoom in and it kind of doesn't have a scale within the computer, and I really love this kind of idea that in the digital realm, we don't necessarily have a scale.

Once you decide to output it and make it tangible and 3-D print i it gets a scale. This dress was also exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, at the Manus x Machina Exhibition in 2016. And it was also exhibited at the Hime Museum and many other places but it was also a part of architecture exhibitions, so this object kind of lived between architecture and fashion world, and I thought this is really beautiful, because having an object which kind of lived within these two disciplines is a really fascinating idea. This one was the first flexible 3-D printed dress and was made with a flexible (indiscernible) material in 2013, and you can see here the development of the geometry was looking at this kind of gradient of lines and this kind of lace-like geometry which is actually coming from the earlier hybrid (indiscernible) dress, the honey colored one, which was the underlying geometrical structure which we developed and turned it into this kind of more organic line work.

This is how 3-D printers look like, which can print with this material. And there's a little video, which shows the technology, how this is done. (Video playing) >> JULIA KOERNER: So this is the selective laser sintering technology where you have a powder, laser i fusing the particles together, almost like an archeological process where you're taking the parts out at the end, taking the powder away.

And this led to a third collaboration with Iris on the biopiracy dress, which was also showcased at the haute couture shows in Paris. This was was also published in the National Geographic's magazine in 2014, next to a 3-D printed ear and 3-D printed NASA suit, so it was kind of one of the early advancements of what showcased what can be done with this technology. At the show itself Iris had collaborated with another artist where the models were kind of shrink wrapped into these plastic bags. It's an artist who does those live shrink wrapped installations and that's where the dress was one 3-D printed dress out of the collection of she had 60 pieces is what she showed there, and it was fascinating to see how far you can push it because you saw the black dress, in the voltage dress, this was printed with six pieces versus this dress was actually many more elements. It had almost 13 parts, which were then hand-stitched together and the kind of holes for the stitching, I already integrated into the digital file. So in the 3-D file I had already made the holes so we would would see where to kind of put it together.

And this dress was acquired by the Phoenix museum of art, and also showcased in 2019 in an exhibition that was digital renderings as part of the exhibition. In 2015 Chanel and Maisson showcased a really amazing haute couture show, where I'm going to show you a video. (Video playing.)

>> Fashion has to follow everyth follow everything that's going o the world, and I like the idea of the most iconic jacket of the 20th century, redone in a technique that was even not possible to im that one day such a thing could (End of video.) >> JULIA KOERNER: So Chanel and Maisson in 2015 realized this collection of 3-D printed Chanel suits where they utilized embodery techniques to kind of combine traditional craftsmanship with innovative new technology. This also in 2015 series of handbags.

This leads me to one of the most impactful collaborations I did in my career, Black Panther in 2018, where I collaborated with costume designer Ruth Carter, the costumes for the Black Panther film, and I'm pretty sure most of you have seen it. I'm still going to show the trailer of the film. (Video playing) >> I have seen Gods fly. I've seen men build weapons

that I couldn't even imagine. I've seen aliens drop from the sky. But I have never seen anything like this.

>> How much more are you hiding? >> We are home. have never seen anything like this. >> How much more are you hiding? >> Let's go. >> We are home.

>> My son, it is your time. >> You get to decide what kind of king you are going to be. (End of video.) >> JULIA KOERNER: So it was really amazing and fascinating to work with Ruth Carter and her team on these costumes and develop those digitally and 3-D print them and to give you a little bit more behind the scenes story ... So Ryan Kugler and Ruth Carter really wanted the regal attire of the queen mother, mother, Ramonda, who you see here by Angela Basset, they wanted her regal attire to be showcasing this kind of technology advanced place, this fictive city of Wakanda and having that kind of idea of technological advancement embedded in her costumes, so one of the things what I was told was that I should really like make it look like it's kind of been hand done. So this idea of kind of the machine being involved and this kind of advancement of materials combined with the traditional Zulu patterns, was something which really Ruth wanted to be embedded in the design, and we worked on a multiplicity of costume parts The crown in black, and you can see here a backstage photograph.

The main character Chadwick Boseman unfortunately passed away last year. It was an amazing opportunity to kind of work with the costume design team. I should mention that this was my first film I ever worked on. At the beginning I didn't even know that I was working on a Marvel film, because when Ruth Carter contacted me, everything was under a strict code name, and and we kind of developed the costumes without knowing who the character would be, and so the 3-D design came in really handy because once the character was cast, we then knew the dimensionand we were able to adapt the digital file later on, in a very short time, change the parameters of circumfrence of the head and the shoulders and so on adjusted it really customize for character. This this is one of the advantages I spoke about earlier, when you write codes and when you write scripts and work with these generative design methodologies, you have the ability to kind of change the parameters at the later time without remodeling everything from scratch essentially.

Here you can see a rendering of the shoulder mantle. As we progressed in this collaboration, at one point I realized which production company it was, and what the film would be, but I think the overall impact I only realized about two months before the film started in the cinemas when the entire entire pre sale was sold out, and I was kind of of -- I felt like, wow, this is really happening and this is so great to kind of be a part of this, and here you can see the shoulder mantle was produced in several different parts and how it was put together. It wasn't developed in parts because of printing constraints. It was more

because of time constraints, because we had to produce it quite quickly, and so we had to print the parts in several several different machines. I worked with my long term 3-D printing partner in Belgium to get a materialized who was part also, a lot of the work I have done before. And I chose them because I had a lot of experience with them over the past 15 years. Now, last image of the film I want to share with you is this, and maybe you remember from earlier the light design I talked about, the new nature light.

So when I went to the cinemas and watched the film and then it was the lab scene where the princess is kind of in middle here, I realized that the lights in the scene, which I had designed with Ross Lovegrove in 2011, so ten years earlier, and it was really an exciting moment to see that, because I literally had no idea that the production designers were putting that into that scene, and that was really exciting to see. Ruth Carter was nominated for the Oscar and asked me to design her a 3-D stole within 3 weeks. So I literally had time between her nomination and the Oscar event to design her this customized 3-D stole. She is the first African American woman to win this Academy Award in this category. And it was really fantastic journey to be part of that with her. And we worked with Swarovski on putting crystals onto the 3-D stole, it was the fastest piece fastest piece I've ever made from 3-D scanning to kind of customize it for her.

It wasn't the first project I did with Swarovski. I had done a collaboration with them earlier in 2018 where I looked into the early stages of 3-D printing with glass with them, and we looked into the development of clear technology in house for the opening of their new manufacturer, Swaraski is an Austrian company, their headquarters is in the mountains, and surrounded by glaciers, so the project is called crystal glaciers, and kind of should showcase the possibility of mass customization and generative design within this kind of technology. The last part which I'm going to just quite quickly through is this kind of way of collaboration and co-production and the way of how I worked with these brands, and with these partners is something something I also bring into the teaching. At UCLA I was fortunate to teach with Greg Lynn for four years in the postgraduate program in the architecture department where we focused mainly on the robotics technology and I utilized in various different technology seminars with the students robotic 3-D scanning or innovative new processes like rotor molding the robots, to create form, which is is kind of taking traditional methods and then combining it with robotic motion. I worked with students on robotic fabric casting and on implementation on assembly structures, 3-D printing with clay those are all mostly independent studies and research what I'm doing at UCLA.

I most recently got some funding to do a project a project from the department of architecture on robotic timber assembly, so this kind of idea of automated assembly and implementation of robotics with CLT or wooden slants and assembly of cellular systems. And besides the last five to six years I've been teaching in the (M Arc) program where I teach design studios with architecture students and introductory design courses. I also teach introduction to computational design, advanced building construction classes, and really focus much more on the architecture in my teaching and academic research, rather than in my professional practice and research. I focus more on smaller scale. Simply also because certain technologies are not yet existing on the larger scale, and only very recently we have seen more and more opportunities within the larger scale of digital fabrication within architecture, such such as large scale 3-D printing with concrete To close the lecture, I'm direct summer programs and we have two very exciting programs coming up in July. One is the Jumpstart,

a four weeks program for high school students and college and Teen Arc Studio, which is for teenagers between the age of 14 and over. And in these two architecture programs, we're going to focus on kind of the early aspiration of architecture and design. And with that, thank you so much for joining this lecture today. And I'm really excited to share my work with you and look forward to all the Q and A.

>> SIMON SADLER: Hi, folks. Can see me or hear me? I can't see myself here. >> JULIA KOERNER: Yes, I can see you. >> SIMON SADLER: You can? You can see me. That's probably a better thing, because I'm sitting here with my mouth agape. I said it was going to be stunning, and, gosh, we were indeed stunned. So

I think you're getting rounds of applause in the chat section I'm applauding. Thank you so much, Julia. Just completely inspiring. Absolutely stunning. So Julia, we don't have a great deal of time, but I was wondering, would you be willing to field some questions? It's probably about 3 in the morning in Jordan, but maybe you've still got some head space because we've got a ton of questions. >> JULIA KOERNER: All right. Okay. Let's do it. >> SIMON SADLER: Great. So I'm not going to be able to get to all of them, but I would like to thank the audience, especially students, for submitting some of the best questions I think I've seen at the end of a talk.

And I wondered if we could maybe gather them together. Apologies, folks, if we don't get to your question. We probably won't. But maybe if we gather it together into like groups of questions, so that we hit each thing that people are asking about.

You know, one of them is the question of breadth. So for example, one of the first questions we had was from Andrea Did you find it hard changing focuses and media over the course of your career? And my colleague, James as well said the work is almost too inspiring. It could be daunting for students just emerging as designers. Do you have any kind of advice for how to approach that? >> JULIA KOERNER: Yeah, I think one advice I have is that often you have something in your mind or you have an idea what you want to do, and then you really want to pursue that, but you realize that it's not that easy, and you realize that there are challenges what you're facing along the way. And so I just want to suggest that you don't get kind of pulled away by those challenges, but rather embrace those challenges because those challenges will guide you in the right direction, meaning I, for example, if I may share one challenge I faced is when I was 18 years old, I was really interested in fashion and architecture. But there was no program existing

which kind of focused on both. Especially in Austria. Everything is so much in categories. Fashion, architecture, product design, it's all so different. And so I applied to the University of Applied Arts for fashion design for the studio of (name) and I really wanted wanted to study there. And I didn't get into the program. And so it was like the same day, I took the train and went today University of technology and signed up for architecture because that was equally as interesting to me. I was like 'okay this is fate' I'm going to start studying architecture, and I started with 500 other students and very quickly realized, wow, public university, 500 students, I've really got to specialize myself to really be able to achieve my goals.

So I actually studied for eight years, so it was a really long time, and I studied with various different institutions, and I had no idea that ten years later, I would get the opportunity to work with haute couture houses on fashion projects. Today I know that if I wouldn't have studied architecture with I would have never gained those skill sets, to 3-D model and to be relevant to the fashion industry, and I was actually able to do those collaborations I think only because I went that route. If I would have gone traditional fashion design, I might not have been able to do this. In the last ten years, a lot of things have changed and there are programs available where you can learn all these techniques equally in other programs as well. But this is just the story of what I can share. That it kind of -- I did a

huge circle to end up where I wanted to be, and I think sometimes you just have to go with what happens, and eventually it will make a closure of the circle. >> SIMON SADLER: That's fantastic, so your career is organic a bit like the design, but what maybe students can take from that is careers aren't linear. We can be looking at your work now, and you can be stunned as to how you ever get there, and the story is complicated and, you know, there's some sort of chance. You know, we got another set of questions, and there's a ton I could have asked you here about the material properties and the process, if you will. I think I might have popped back there. I could pull one out here for you from Mikeala, and apologies, folks, if I mispronounce names. Mikaela says, is there a natural element you would like to utilize in fashion any other design through 3-D printing that you've not tried so far? >> JULIA KOERNER: Yes. I would really love to explore 3-D printing with natural fibers,

and that's simply not yet -- I haven't come across any process where you can do that and I've seen you can print with carbon fiber with more rigid fibers, but but I don't think there's anything out there where you can print with cotton or with natural fibers because there's always the heating process involved, so I think something where the closest we come to that is with 3-D 3-D knitting perhaps, but it's a different process than the printing, and that then is something I would really like to explore and look forward for some researchers to develop some processes with that. >> SIMON SADLER: Fantastic. I'm going to move to another set of -- hold on. This was really interesting. Actually maybe I can do this one as well then We're gathering things here under material properties and processes, so if I was to try something else here, this is from from Zach. What software do

you use for your 3-D modeling and how do you go about networking, because it seems like you have able to collaborate with lots of other amazing creators? >> JULIA KOERNER: So I use architectural 3-D modeling modeling software, such as vinyl, I use a lot of grasshopper, which is a generative design, a plug in for rhino. I also use polygon mesh modeling softwares and I really use a lot of open source softwares as well. I kind of don't have one specific one I work with. I kind of really always look what's most applicable, but yeah, rhino and grasshopper would be the main ones, and then I kind of look what's needed. In the research project which I showed with the fabric where I mapped it onto the body, I also worked with Clove, with CLO software.

it's always different. >> SIMON SADLER: Hm. Now, we got a bunch o questions around sustainability, costs, and equity. That's a little category that I'm creating here. And these are questions from people like there's Jazzy, Muriel, Yang, Lilly. I'm going to mush these up into a composite question. Muriel: "Happy Earth Day.

I love how you take inspiration from nature. With the job that you do, how do you keep your designs sustainable and safe for the Earth? And if I can just sort of tack on other things there. Sustainable products, this is from Lilly, have more care put into the quality but it could mean that prices prices are higher, because a student without much financial flexibility, are there ways we can practice sustainability in our work? Similar sort of questions there about costs quality from Yang. Jazzy too, wondering like would it be one day possible to mass produce work for efficiently, more cost effective, So as I say questions there about sustainability and equity, and well timed for about now. JULIA KOERNER: That's a really great question and one I get a lot, and maybe something I don't talk so much in the presentation, but more in Q&A sessions. So. You saw how I built up my presentation also. A lot of the early parts

were kind of university things, what I showed, and then research and then I showed a large majority of work which was my own research. Now, you might wonder how do I fund this, right? I don't come a rich background. My kind of resources are limited, so I look a kind of collaborative projects with brands also as kind of way to then fund my own research projects. Or I look at grants which are either from Europe or from the U.S. or less from

the U.S., more from Europe, where -- which helped me to fund some of these research projects. Then the other source I find is that I collaborate with great innovative 3-D printing companies, and so I was both lucky but also really hard working to kind of put myself on the forefront of this technology so that I got 3-D printing companies approaching me and saying, hey, we have this new technology, would you like to try something with it? And then you become so specialized in a niche where there aren't yet many many other people, then you get these kind of opportunities. That also means that you have to

put a lot of time. There's not necessarily money what you get through that, but you get the opportunity to test new technologies to make a project with that, which you then can utilize to maybe win another project again with it. And so there isn't necessarily a linear route of I would say methods. It's kind of a diversity of different projects, or in terms of equity, I would also like to say that one thing that was really great about Black Panther was that it was one of the first projects which was— had a reach which was so broad that it wasn't only limited to a closed circle, like the haute couture. There's amount of people who can go to a

haute couture show in Paris, but there is obviously now, with the pandemic pandemic, this has changed a bit, because everything is more virtual but the Black Panther film really had an impact because it was -- everyone could go to the cinema or watch the film at home, and it was therefore the reach to the public was much broader, and I had friends in Austria Austria who never really understood what I actually was doing, reaching out to me and say, Julia, you finally know what you're doing even though that isn't' necessarily what I always do. That was really nice, the kind of working with the costume industry gave me the ability to have a broader reach and reach more people to show what this technology can do. Yeah, and then toward towards sustainability, as you can see, I shared a lot of ongoing projects at the beginning of the lecture, where I'm really focusing more on how can we implement the sustainability aspect of the materials The Setae jacket, which is also in the background here, that one was printed entire without without support material, and so I had to kind of sacrifice on the complexity of the geometry geometry and do the little sticks, which are possible to print without support material, but at the same time eliminate eliminated any waste material, and then then I looked at printing it on natural fibers so that you can kind of reduce the water consumption, and if you think of that as how we could implement that on a mass customized way or mass production, we could bring down the cost of of that, so right now it's still a non-commercial technology not a lot of people are utilizing it yet yet, but it yet, but I see opportunities with what But I see opportunities with the in-house printing. Like ...

You can buy now a 3-D printer now for less than two-hundred dollars. That was impossible 15 years ago. That was just not existing. So we see there's a lot of change coming, it just takes time. But there is a lot of resources a lot of universities now have 3-D printers, there are labs where you can go to print your ideas. So it seems the technology is much more embedded now and more accessible than it was some years ago. >> SIMON SADLER: We got hopefully time for maybe one or two other questions.

We're going to be wrapping up in five minutes, and it will be nice as well if we can leave just a little time to see if we can hear the chancellor's introduction, so it will be an outro instead of an intro. To loop back to the Black Panther. You talked a moment ago about that and it was a collaborative work. This was

a question from Candice: Did you draw the inspiration for the Black Panther costumes from existing cultures? If so, how did you conduct your research? Maybe there's a possibility there of thinking about the collaboration? >> JULIA KOERNER: Yes. I got everything from Ruth Carter. So I got like a book which was about African illustrations, and I looked at traditional Zulu patterns, and then kind of took those geometries -- not geometries, took those illustrations and translated them into 3-D just as an initial starting point for the design. And I think the costume department on their end did a really long research into those patterns, and they -- that was all done by Marvel and by Ruth Carter. So my part was I think I worked with them around three to four months, and in that process I was literally given the kind of patterns they wanted to work with already, so I wasn't that much involved in the initial research of those geometries and designs, but more on the kind of applications and implementation. >> SIMON SADLER: I want to do a fun closer if I can. This was from Kelly.

What do you like to do when you aren't working on these projects? What do you do while you wait for the columns or your projects to finish printing? >> JULIA KOERNER: That's a really great question. So I really like to be out in nature, and I also like to sometimes not do anything, because I have these kind of phases where I work really late and really long hours and do a lot of things. But sometimes I also just like to relax and I also like to travel, and I have to travel a lot due to a lot of these projects, and so, yeah yeah, I like to spend my time with family and friends and -- but I'm more like an outdoor person. I like to go to

the beach in LA. I like to, you know know, do regular things. I like barbecues barbecues and, Right now I'm in Jordan at the Dead Sea looking at salt crystallizations. I found some nice objects today on the beach and so I take every opportunity to look at what nature and what Earth can give us, and so maybe that's a great way to close this lecture on Earth Day. >> SIMON SADLER: It is an absolute gift and it sounds perfect. So what I think we'll do then is thank you once again Spectacular and inspiring, wonderful talk.

2021-05-02