Dr. Brenna Clarke Gray on Recognizing Power in the Generative AI “Revolution"

» DR. ALEX KETCHUM: Hi everyone! Bienvenue. Welcome! Thank you everyone for coming to the 91st event of Disrupting Disruptions: The Feminist and Accessible Publishing, Communications, and Technologies Speaker and Workshop Series! I'm Dr. Alex Ketchum and I'm a professor of feminist and social justice studies at McGill and the organizer of this series. The Feminist and Accessible Publishing, Communications, and Technologies Speaker and Workshop Series seeks to bring together scholars, creators, and people in industry working at the intersections of digital humanities, computer science, feminist studies, disability studies, communications studies, LGBTQ studies, history, and critical race theory. I'm so excited to welcome you all! Some notes on accessibility. As is the case with all of our hybrid and virtual events,

we have CART captioning in English, tonight provided by our captioner Fenella. You can turn your captions on at the bottom of your screen. Tonight we have a Q&A option available. So throughout the event you may type your questions in the question and answer box and there will be some time during the second part of the event for Dr. Brenna Clarke Gray to answer them. We can't guarantee that every question will be answered, but we are grateful for the discussion that you generate. ended just want to emphasize I strongly encourage you to type questions during the event as that will mean that when we get to the Q&A period, you're not typing furiously. We have quite a few more events coming up this semester. Our next event is on this Thursday. On February 15,

Khari Johnson will speak about AI and Journalism At six p.m. Eastern time also in virtual format. On February 21, 2024, Dr. Mél Hogan will speak about the Environmental Impacts of Chat GPT and AI Technologies and on March 15th we are co-hosting a workshop with COHDS which is the oral history and digital 's storytelling on queer oral histories. Gabrylle Iaconetti and Liam Devitt will be speaking at that hybrid event. You can find our full schedule as well as video recordings

of our past events at disruptingdisruptions.com. so that's the redirect URL. The other url is too long to remember. You can also find our list of sponsors including SSHRC, Milieux, ReQEF, and more! As we welcome you into our homes and and our offices through zoom and you welcome us into yours, let us be mindful of space and place. As many of you know,

past series speakers Suzanne Kite, Jess McLean, and Sasha Luccioni have pointed to the physical and material impacts of the digital world. The topic of the environmental cost of digital technologies will also be addressed this semester in other upcoming events. While many of the events this semester are virtual or hybrid , everything that we do is tied to the land and the space that we are on. We must always be mindful of the lands that the servers enabling our virtual events are on. Indigenous communities are disproportionately impacted by the mining practices used for the materials that are used to build our computers and digital infrastructure. Furthermore,

as this series seeks to draw attention to power relations that have been invisibilized, it is important to acknowledge Canada's long colonial history and current political practices. This series is affiliated with the Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies of McGill University. McGill is located in Tiohtià:ke Montreal on unceded Kanien'Keha:Ka territory. Furthermore the ongoing organizing efforts by Indigenous communities, Water Protectors, and people involved in the Land Back movements make clear the ever present and ongoing colonial violence in Canada. Interwoven with this history of colonization is one of enslavement and racism. This University's namesake, James McGill, enslaved Black and Indigenous peoples. It was in part from the money he acquired through these violent acts that McGill University was founded. These histories are here with us in this space and inform the conversations we have today. I encourage you to learn more about the lands that you are on, Native-land.ca is a fantastic resource

for beginning. Now for today's event. Dr. Brenna Clarke Gray is a critical educational technologist working as a practitioner/researcher and theorist. She is also an academic podcaster. And I have been such a fan of her podcasts, including her podcast On bio literature Hazel cat and the star. Her focus is on the ethical, accessible, and care-informed use of digital tools in education. Please join me in welcoming Dr. Brenna Clarke » DR. BRENNA CLARKE GRAY: Thanks so much for having

me and for being so patient with me through the process. I know organizing at speakers series is always like herding cats and I've been like the caddy is So I apologize that and I'm grateful to be here. I'm just going to get my screen share started here. Where did you go because Zoom? It's always fitting for the educational technologist to have a hold bunch of trouble getting her screen share. I feel like I'm modeling grace when...There it is. Welcome, everybody. I'm so glad you're here. I'm here today to talk about the whole bunch of things . Inevitability discourse, generative AI, how these technologies embed themselves in our institutions and particularly in institutions of teaching and learning as that is my priority. My talk today is called

every technology was somebody's choice resisting inevitability discourse and recognising power in the generative AI revolution which I've put in air quotes. As Alex said my name is Brenda Clarke Gray and I'll talk a little bit about that role. And how it shapes the work that I do and what I understand of these technologies as we chat today. Thomson Rivers University is located in British Columbia which is.[word?] Territory within the...We are learning has taken place since time immemorial . It's an absolutely glorious day here today. It's exactly what a winter day in the BC

interior should look like . It's snowy and it's below zero and the skies bright blue and it's a real relief because we've had a distressingly warm winter after a distressingly hot summer. Of forest fires that I think a lot about the territory I'm on an stewardship especially as we talk today about generative AI. One of the things I want to discuss is how the water and current impacts

of technology like generative AI fits in with mandates that many of the universities have to be sustainable . To be environmental stewards so I'm hoping we can talk about that today. If you're interested in supporting land and water defenders really strongly recommend Raven trust were raising money to support the wet swidden land and water defenders which in this territory is really important urgent critical work. Finally this image is a photo of the beautiful sky in nuts for which is just south of Kamloops and it's an area that was really tremendously affected by the forest fires this last summer. I just love looking at it in this moment of calm. I do like to let people know that you are more than welcome to share anything I took about on social media today if you wish . I just like to make sure people have that consent right up top. I no longer have a presence

on X but you can find me on mastodon.social, blues, cut Instagram and all those places . I'm at Brenda C Gray. I'm also going to share links as ago along today and you'll see that Bronwyn was kind enough to start a question in the Q&A for me and I'm going to be putting the links in there as I go today so you can follow along with some of the resources that I'm going to share. A little bit about me and my contexts. Before came to educational technologies, I spent nine years as a community college English instructor. That's my disciplinary background. I was a literature scholar first and I transitioned to faculty supporting 2019 months before the pandemic.

I have is I always joke right at this point impeccable timing. Coordinator of educational technologies is a faculty role and it's a very multi-unique role in the post-secondary landscape I think because I am a faculty member, but I'm here to provide faculty support around technical and pedagogical issues. But it also I'm here to give institutional guidance and framing particular around a new and emergent technologies. That's what I have been doing

with generative AI for about the last 18 months of my life. It really does feel like generative AI has sucked the oxygen out of the room for a lot of my day-to-day labour when I'm helping faculty hands-on. I'm also in an interesting period of transition because as of July 1 my appointment is changing from professional role faculty appointment to becoming a research professor. How that's going to change I'm not quite sure yet but it will be an interesting period of transition as I get to focus more on the research piece of my work. I think something that's important to talk about today before I'm position myself as an expert is some very suspicious of expertise when we talk about the pedagogical implications for artificial intelligence. There are lots of people who are happy for you to spend a few thousand dollars on the webinar series where they teach you how to teach with generative AI or they teach you how to check students work for generative AI. This technology is very new . Obviously AI has been around for some time.

But why --widely accessible generative AI tools like ChatGPT are really new and I not sure we have true answers about the implications of these tools yet. Even as universities want to make headlong into the new technology to make sure we have all the competitive advantage in place, I think that maybe what we should really be advocating for is critical distance and pause. So we are going to talk a bit about that today as well. I guess that last point probably precludes the next point but I'm kind of a killjoy when it comes to technologies. I really do love working with technology. It's my daily work and I enjoy helping people find the solutions that they

need to the problems in peer classrooms where technological solutions exist. But I also think that there are much more important issues to consider. Things like the sustainability of the technologies we choose, the ways in which the technologies we choose embody ethics of care, larger ethical ramifications, things like student privacy. These are things that I really prioritize over and above shiny new technologies which sometimes makes me feel like a bit of a Ludite but we are going to reclaim that word today to so stay tuned. We don't have a traditional chat but I do always really like to know where people are coming from, what has brought them out to a conversation on any given day. I'm hoping that you might share in the Q&A what your role isn't

what brings you out to our conversation. I've also said are you worried about AI? Excited? Hopeful? Deeply paranoid? That's me. Too tired to care? It is February. I was saying earlier today I don't know about you guys but our reading break is next week and you can kinda feel the collective need on campus from everyone to just take a nap so I do get the fatigue and exhaustion then checking out as part of this discussion too so I'm hoping you might share in the Q&A what brought you out to our conversation today. Exciting. We've got folks from Wisconsin in the Q& A. That's very Cool. >> DR. ALEX KETCHUM: I will answer live so that way people in attendance will be

able to see the results so they can see. » DR. BRENNA CLARKE GRAY: Awesome. Yes. I see. Gotcha. Graduate student joining us from Tucson , Arizona. Fantastic. Welcome. I always tell my students that I can outlast any awkward pause that they think that they can throw at me. I will wait it out while folks type . Very curious to know where you're joining us from today. Heidi,

hello. Welcome from boatswain college my neighbour here. A group of graduate students in Intreo. Welcome. Hi Lorraine joining us from Toronto. Lorraine who I own email. Welcome. So nice to have folks here. Love they'd have friendly faces. Michelle new UMass nice fantastic. Graduate student from McGill. This is great. Delighted to see folks here and the range of perspectives. The range of approaches . All my goodness. (Indiscernible) I was just in the session earlier today sharing resource 's fantastic. I use it all the time. Thank you.

Welcome. that Monash has made about generative AI for students. ItJennifer Andrews. I know you. Jen was my PhD advisor. Joining in from Halifax welcome. Open aid worker at the moment from Italy. Thank you so much for joining us. Madeleine from McGill welcome. Feel free to keep sharing with me in the chat . I love knowing where people are joining us from. I'm going to bounce along in my slides but don't let that stop you. I want to start with some basic definition of

terms . Sometimes when we talk about generative AI it does feel like everybody's on a different page and my background I'm very open my background is as a literature scholar. I am not an AI researcher in the pure technical sense of the word. So I'm going to share with you my working definitions

that I find useful from the perspective of education. Many of you may have a much more refined sense of these terms, but this is sort of where want to start. So AI versus generative AI. Something I like to remind us is that AI has been part of our educational landscape for really long time. Any of us who have used the Accu placer test for placing students in their English classes for

example, that is using an AI technology. It's a real catchall term that encompasses a wide range of machine learning technologies that use large data sense collections of information effectively which we will talk about today to make predictions or conclusions. AI can be classified as narrow, general and super . Sometimes we use the term weak AI to describe narrow AI. And that's where I is designed to complete a very specific task. All AI we can currently access is narrow or week . In the

world of artificial intelligence general and super AI so general AI would be comparable to human capacity . Super AI would be superior to the human brain. Or human intelligence as we understand it anyway. Those are theoretical. It's really important I think to remember that because it's very easy for generative AI to get a bit oversold or overhyped in terms of its capacities and what it can do. Week AI does not have consciousness or self awareness. Sometimes it seems like it does and can depending on how much your Syria talks to you. But these are not sent to and technologies. Generative AI is part of this band of narrow AI and it's a class of tools where AI doesn't only make decisions or predictions but instead uses that same capacity for decision or prediction in order to create, to generate perhaps . That's what we talk about when we talk about generative AI. Straight up AI like machine learning sort of predictive conclusion based technologies,

we've used those in education for a long time. Some registrar's office 's use them to sort applications . As I said tests like Accu placer to place students in their appropriate level of English class for example. Those are all using those kinds of technologies already. If you

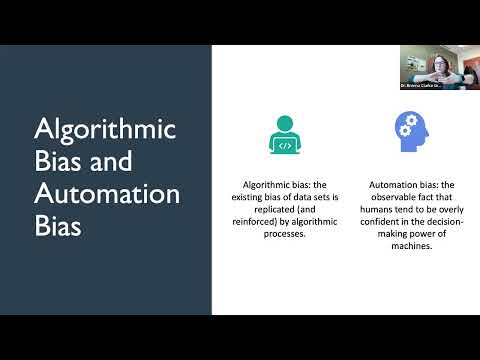

have learning analytics at your university that flag when a student is quote unquote at risk, again probably some kind of machine learning tool underpinning that. Generative AI is this thing where we have generation , creation. Some key terms I want to kind of go over as well though because it's going to come back as we talk today. Our algorithm algorithmic bias and automation bias. Algorithmic bias is the existing bias of data sets that gets replicated and reinforced by algorithmic processes. This is the idea of garbage in garbage out. When we have bad data that goes in or biased data that goes in to a data set, the outcomes will then necessarily also reinforce those kinds of biases. There's a really great visualization that Bloomberg

did last year about stable diffusion text image model and the way in which it amplifies stereotypes. This is a great one for sharing with undergraduate students as well . It's very clear visualization of how bias functions. Oh dear. I just answered my question. I just popped that and if you're looking on the Q&A panel where Bronwyn had the question at the top of the list, I've added the quote in there so if you click show all you should be able to see it so I put a link in there. Another really interesting recent piece of data connects to this idea of automation bias. Automation bias is something I find fascinating. It's the idea that humans tend to be overly

confident in the decision-making power of machines . We really seem to want machines to give us some sort of unbiased answer. And I think this comes from a good place. I think we all understand the history of bias in human decision-making and there's a real desire to find a solution to that problem and often we look to computers for that. But you can see how this is a reinforcing problem. If there's already bias potentially built into the data sets and then we are more likely to believe the solution that comes out of the data set, you can see how the reinforcement of bias can happen. I was reading in absolutely fascinating article in scientific works this morning which actually suggests that and go on to inherit the biases of the artificial intelligence tools that they're using. Partly because of this idea of automation bias that we are so interested in believing the answer of machines so I'll put that link in the chat as well. This leads me to a term that I

didn't have a good word for so I gap. This is the distance between the decision-making entity and the person actually responsible for the decision. In example I like to use is if you follow Tesla and their self driving car technology only that Tesla is working very hard in courts all across the US to make sure that Tesla itself as a company is not held accountable for what self driving cars do. There we have an accountability gap. We have a technology that's doing one thing and we have

the entity that creates the technology not taking accountability for it. The response is of course that there should be a live driver in the car who makes all of the final decisions about what happens behind the wheel of a car. But of course if we come back to this idea of automation bias, we can see how second- guessing your own decision-making when the machine is telling you that something else is a better choice is super possible. To what extent should we

expect companies developing AI technologies to take responsibility for the technologies they develop and the consequences of those algorithmic decisions? That's something that we are obviously still working out as a society. Those definitions out of the way although we will come back to the mall cut today what I want to talk about is inevitability discourse and technology. What does it mean to accept the narrative that a technologies here and it must be integrated into our practice? My focus is on education and I 'm going to be talking mostly today about generative AI from the perspective of teaching and learning practice but I think this applies anywhere that generative AI touches. I think that we are all teeing told that this technology is inevitable, and we must adapt to it immediately. While I understand the desire to ensure that our practice is up -to-date, that we are aware of emergent technologies and trends, I also think that this discourse of inevitability really limits our ability to make choices. And to opt out if opting out is what's appropriate for our contexts. I found a Marshall McLuhan quote.

McLuhan fan or not I love this quotation from the medium and its message which is there's no inevitability as long as there is willingness to contemplate what is happening. One of the things I want to talk about today are the ways in which being told that a technology like generative AI is inevitable, that it's here to stay, that we must adapt our practice to it, it's like a thought remaining cliche. It 's designed to stop us from thinking critically about the technology and to simply embrace it. I really love McLuhan's point here that as long as we are willing to pause

and contemplate and ask questions, then nothing is inevitable. I hold fast to that as you'll see as we discussed today. Something that I spent a lot of time thinking about is the ways in which technologies come to us always through a series of choices. Oftentimes those choices are rendered invisible to us particular in our working lives. But every technology is a product of a series of choices that have been made. There are no technologies in the digital realm that have simply sprung into being and then emerged on our work desks . They are all a product of choices.

Sometimes the choice is ours. Sometimes we have a specific solve them probably want to solve and we go looking for a technology to resolve it. In our working lives the choice is almost never ours. I've become very interested in procurement processes really from the experience of being a faculty member and finding a new technology arrives on my desk that I must adapt to, learning and judgment system changes. We subscribe to a new email delivery vehicle. Whatever it is. This

technology shows up on my desk and I just have to adapt to it. It just has to be part of my working life. I never felt like I was a part of those processes and that is what led me to thinking about processes of procurement and how we follow them. And what a process of procurement says about the values of an institution. I think there's this important thing where choice gets codified by our institutional values. Sometimes we express them aloud and sometimes we don't. But as we talk about today, there are lots of technologies that our universities adopted and embrace that we know cause harm. Somewhere along the way someone has gotten out a scale and with the possibility of

what the technology offers against the harms that we know it causes and decided the harms were worth it and that's procurement process and I'm really kind of fascinated by our institutions. But the important thing is in neither of these examples are these inevitability's. Somewhere a technology has been determined to solve a problem, resolve an institutional issue whatever. But somewhere along the way someone has decided that these technologies are the ones we are going to use, that they are successful and useful. And yet it does feel inevitable, right? I'm not going to

stand here and gaslight you and say generative AI doesn't feel inevitable. What's the matter with you. You open up a newspaper or turn on the CBC, engage in the world and everybody is telling you about how generative AI is changing everything and we're definitely going to this moment where if you market and educational technology and you don't have the phrase generative AI in there somewhere, it's like people alike what's wrong with technology. I think they're a bunch of reasons why generative AI in particular but any technology might feel inevitable to us and one of them is media saturation. There are so many pipe stories about what generative AI can do and much less discourse about its limitations or problems and some of the kinds of ethical issues that I want to talk about with you today. I also think that within the University in particular but likely within an institution we can feel really alienated from the processes of procurement. Even

in my role now I'm not involved in understand how it works even now. Even though now I write about procurement processes. There is an alienation or isolation from the decision-making that happens and I think that that is something that's worth us talking about and surfacing within our does our procurement framework look like? Does it . It's very difficult to find out information from ed tech vendors that they don't want you to have. And in the case of something like generative AI tool, the datasets are obvious gated. It's difficult to find out what goes into them. It's difficult to find out whether the material in them is of good quality or not. In fact it's a most impossible

to find that out. And so in these technologies just kind of appear and many of us don't have a good sense of words come from or where it's emerged from, that can feel really like okay, I guess it's here. Then of course something will come back to later today is this idea of Luddite discourse. Nobody likes to feel like they are on the outside looking in. And often times, it can be a very strategic choice for us to be made to feel like if we're not adopting a technology immediately then we aren't with it. We aren't maintaining our practice. language is used to really make people think that they don't have a choice. For all of these reasons, even

though I'm going to tell you a bunch today that engaging with generative AI is not inevitable, I get why it feels like it is. Goodness me. There we are. That's what I want. I think institutions underscore this inevitability. Something I think about a lot is the extent to which we can opt out of a technology. I support our learning management system here at TRU. A lot of my work is doing exactly that making sure students can gap their assignments and then faculty can use the learning management system we use Moodle to the best of their ability to do what they needed to do, spend a lot of time at it midterm and exam time setting up quizzes and fixing great books. It's a big part of my job. Something I think about a lot is that when students first log into the system, they

get what we might call a click through consent. It says do you consent and then they click yes and then that's it. There's no real mechanism for them to opt out. I think a lot of time about how I don't know what I would do if a student said I'm not going to opt in to use the learning management system . What next? I don't have a process for that . I guess I'd have to go in talk to their

faculty individually let them know they are opting out of this technology. We could talk all day about whether or not click through's are informed consent. Given how quickly I scroll past the terms of use on my phone every time I update it, I don't think they are particular meaningful forms of consent. But it's worth thinking about as institutions, ostensibly is research institutions we might value the notion of informed consent . And yet we have our students go through these sort of performances of consent. Yeah, technology feels inevitable when you can' t actually opt out

of using it . Right? Most institutions faculty could opt out of using the management learning system although there can be a ton of pressure from students ...so that differs by institution as well . Everyone should have the rito law opt out of a technolog. And my big question often is does the procurement actually reflect institutional values? That is a loaded question because sometimes the answer is yes, but you don't actually like with those institutional values truly are. I give a session earlier today where I wanted to look at the difference between what we say our institutional values are and then how we live them there procurement processes. I'm not going to untie that whole knottoday but I do think it's worth thinking about if we say sustainability is core to our institutional values, but then we use the contract with the technology that has a massive carbon footprint or mass of water use like we are going to talk a bit about today, one thing is just the thing we say in one thing is the actual outcome of our we espouse as our institutional values I think is important. We can see this in the technologies we choose and an

example when I think about harm and procurement, the example I always come back to his algorithmic test prop during . Most processes of procurement as far as I can see don't account for anything like harm reduction or mitigation. These are not documents created from an ethic of care philosophy perspective. The reason why think algorithmic test proctoring is a real usable case study here is because the harms that the technology causes are really well-known. To take a step back if you are

not familiar algorithmic test proctoring software is technology where students write their exams usually from home rather than coming to campus. Sometimes in the testing centre depending on how things are set up. The cameras watching them take the exam. They usually have to do a room sweep with the camera before they begin. Then some do or don't employ human proctors but there is an algorithm or other rhythmic process running at the same time that's determining sitting behaviour. That's loaded . What is a normative exam sitting behaviour? We know from research into these tools that for example students usually have to show their student ID and then their face and there's a facial recognition process that goes on to authenticate the student against the ID. Well,

we know the facial recognition technology is very poor for people with dark skin, really any People of Color but the darker your skin the less likely it is that a facial recognition technology will recognise you. Also maybe you don't present your gender the same way as your gender is presented on your university ID card. Those are two cases where right from the experience of sitting down to take the exam a learner might be told you do or you do not belong here. But there's either a space for you or not. We also know that neurodivergent students and students with other disabilities are often flagged as having nonnormative test taking behaviours. These are often things like looking

off to the side instead of maintaining eye contact with the computer itself during the assessment. It could be fidgeting behaviours . There's any number of things that might deemed nonnormative or in some way suspicious. A really great resource about the harms of algorithmic test proctoring is an article that Chase Walder wrote right at the beginning of the campus were turning to these technologies where he warned about a lot of these issues. I've just added that to my littlest in the

Q&A. That's an example where we know that there's a lot of harm being caused to already marginalized learners within the institution and yet many of our institutions contract with this technology anyway. It's a difficult thing to talk about but really what's happened there is that a scale has been sort of measured and we've put the bucket of harm on one side of the scale and the other bucket is things like the convenience of the institution for be able to assessment practices but rather maintaining the high- stakes exam for whatever reason. Sometimes there are external pressures, licensure agreements but whatever they are, we've decided that they are worth the harm to this bucket of students and of course often on this equation happens nobody's doing this out loud. Nobody standing they're doing this out loud but these are students who are likely

already marginalized within the institution and other kinds of ways. As I look at the kinds of practices that I'm seeing around generative AI another technology that really concerns me in this regard is generative AI checkers . Tools like GPT0is one. Tools where you put a students scorecard tells you whether or not this thing was generated by AI. First of all, that technology is really crappy . Just as a disclosure statement, it has a very high rate of false positives. But when you drill down into the data. We know that learners for whom English is

not their first language are much more likely to be flagged . There's really robust research that supports that. And there's nascent research to suggest that neurodivergent learners are also more likely to be flagged as being AI when they have actually written the text themselves. There's another example where there's clearly a problem that we are trying to solve . Wanting students to do their work to not engage with generative AI. And some of us are saying okay,

these harms -- I'm either not aware of them and I'm not doing the research to find out about them which is one of students and this is a large bucket of students and this is what I need to accomplish. We get driven into a lot of these decisions for all kinds of structural reasons. Scale, huge class sizes, not enough time to prep. There's a million reasons why these technologies come to be popular. But those reasons don't diminish the harm for the individual learner

who gets harmed by these tools. I'm going to talk about specific harms from generative AI in just a second. But I do think it's important that we recognise that every time we interact with these tools whether consciously or unconsciously we're doing some math. we're deciding what amount of harm is acceptable to make use of these tools. I think that particularly on an institution wide level when we start to think about things like competitive advantage or reputational risk around not adopting these technologies, that's a really clear example . As we start to unpack some of the

harms of these tools I think that will become may be more clear. This is from a fantastic essay in I will say a fantastic collection which I don't just say because I have an essay on procurement in this collection. But I do encourage you to read it. I'm going to share this link in the chat to artificial intelligence for good? Challenges and possibilities for AI in a higher education from a data justice perspective. I like the perspective here. She 's much more of an optimist than I am. She notes here principles of data justice informed by empathy, antiracist philosophy, ethics of care and trauma informed teaching must take centre stage to ensure AI technologies do no harm. The truth is that educational technologies as a discipline, as a practice at all of our institutions is really behind on all of this. It's a very rare that we have the opportunity

to put empathy antiracist philosophy, antiracist and trauma informed teaching ahead of what the technological tool does when we engage in those procurement processes. I'm not aware of any where those ideas are really taken seriously and I think that may be the generative AI moment because we are recognising it as a sea change and a big shift is perhaps a time when we can revise some of our institutional practices to really think differently . It's a frustration to me that after everything we 've learned in the pandemic where so many of us were rushed quickly online car rushed quickly into our learning management systems and learn firsthand just how much the tool that we have access to can circumscribe what we can do in the classroom that we still treat the procurement of technologies like we treat the procurement of furniture. It has a very profound impact on our teaching and learning practice. And it needs to be recognised antiracist philosophy. All those things that should be at the core of our practice. I'm going to quote from one of my absolute favorite essays of all time by Audrey Watters who no longer works in the ed tech space and I think all of us were critical educational technologist Mr. Ed very day. This is an essay called hashtag team

Luddite understanding of what a Luddite is our popular where Watters makes the point that our historical understanding of what a Luddite is intimately misunderstood. The Luddites weren't opposed to technology conceptually. The Luddites wanted to maintain control of their worker, creative outlet. They wanted to maintain their role as artisans and not become (Indiscernible). That's really who the Luddites were. Waters embraces the term . In that essay she of itself. Are you for it or against it. It's the technology is necessarily encased in structures and systems that we need to interrogate. Those who are quick to dismiss criticisms of those most

invested in protecting the structures and systems of ongoing exploitation. Nobody goes harder than Audrey Watters and I respect her work so much so let's take a look. What are the systems of ongoing exploitation in generative AI? Well, there's a lot of them. We have invisible eyes, under compensated labour in the moderators union. You may remember this time article from last

year. here. ChatGPT did not emerge out of nowhere . It's based on a framework GPT 3.5 and now if you use the paid version you are onto GPT-4. All that is based on previous iterations and GPT three was quite good. He could generate text really well. It was also super racist, super sexist and said

horrifying things, wrote all kinds of violent content . It had been trained primarily on the same kinds of databases as GPT 3.5 which we know as ChatGPT now. Which is remarkably -- there's a lot of bias there and we'll talk about it but it's not as overtly racist. I remember when ChatGPT first launched people were like wow, they really fixed that whole sounds like go 4Chan kid aspect of GPT. Grade. And I think we were very much encouraged to believe that that was OpenAI

developing the technology more effectively. That's not what happened. OpenAI hired large teams of underpaid labour in the global South in Kenya specifically at a rate of about a dollar 32 to $2 US per hour to go to the GPT dataset and remove or tag anything horrifying. That included child sexual assault materials . That included representations of sexual assault. That included representations of violence . Representations of some of the most horrific crimes that you can imagine. The people who did that work reported the work as being horrifically traumatizing . Lack of support for that labour being done . Now the African content moderators union isn't

just OpenAI contract workers. It also involves people who do content moderation for TikTok, Meta,, for really almost all technologies that are widespread and in use in the global North. What's fascinating about this story, in addition to a just being horrifying, is that there are a lot of layers of exploitation upon which this labour functions. A lot of invisiblizedcontent moderation labour performed for most technology services is done in the global South in countries like Kenya and India were a lot of educational language instruction is in English. There's a huge body of highly skilled, very competent English-language workers who can undertake these tasks at incredibly low wages and without the kinds of protections that they would expect to be afforded if they did this work in North America or Europe. This is true across the ed tech spectrum.

If you use a proctoring service that allows your students to book an exam at two in the morning or two in the afternoon, you might want to look at where those workers live and what their conditions of labour are. For all of these reasons, most educational technologies don't function without some form of exploitation or labour and Alex made the point of the top about the exploitation of mining for the very pieces that compose our technologies. But with the Kenyan workers and at the time expose it evoked some really salient concrete examples and I like to point this out in relation to university priorities like decolonization . University priorities like equity and social justice. Where does this fit when we're working with these kind of technologies? Two a may be more well-known example obviously copyrighted material script for data sets without consent.

This is a fascinating one because people working in universities embracing a technology that is entirely based upon the collapse of the notion of intellectual property is something I find truly fascinating. Our eagerness to jump onto this technology. If you wrote blog posts or posts if you are Reddit user prior to 2019 it's probably possible you have writing in the data set for ChatGPT in particular. That was scraped without your consent. You didn't consent to that use of your data. What we 're increasing finding is large language models is can demonstrate the

copyright of their work as we are seeing with more and more authors and consortia of authors who are suing OpenAI and Meta and other technologies we're seeing that they are not holding up in court. As I'm going to say in a minute this represents a huge shift in the way we think about what it means to create something. And your ownership over it and your own intellectual property. It also because the data sets themselves are obvious gated, the other norm that it really breaks down and am going to talk about this in the second is the idea of being able to trace something back to its roots because we can't see inside the data set. ChatGPT just spits out an answer at you. I'm fascinated by the extent to which the way we prompt has an impact here. I'll get into that

in the Q&A if we have time. Then extreme water use and carbon footprint of AI tools. This is the thing that has changed my practice. In these kinds of talks I use top onto ChatGPT into the prompts live and we talk about them together and we change it up. But then I found out this really

interesting early research into how much water ChatGPT -- any generative AI technology uses. It's a preprint article. I'm popping it in the chat because I think it's really important one. The estimate that this article comes to is that an average chat with ChatGPT so around 20 to 25 questions costs about 500 mL of clean drinking water. I don't know where everybody's from although I I saw some responses from other fellow folks who live in a desert. I live in the desert in interior British Columbia here. I know how precious our water is. I have a very vivid understanding of that every single summer when the wildfires burn. And I change my practice

sorry generative AI Howard search probably has about five times the carbon impact of a regular search. This is something that bothers me because you don't get to choose whether your Google search is a high-powered or not. You just have to kind of take what he gives you. I work at University that claims to be the most sustainable University in Canada. Although sometimes I say that at these

talks and says my university claims that so I don't know. I'm not the sustainability police. But it's wild to me that our goal to be the most sustainable University in Canada doesn't seem to be at all in conversation with our choices to use these kinds of tools . It seems to be to have a massive impact on whether or not our practice is actually sustainable. As I've suggested we are in the process of huge shift in norms that impact the University as a structure I believe. I've

already talked about the notion of intellectual property . But to me this is huge. The idea that your body of work can just be scraped and used to create a machine that spits out things that sound like you . That's wild. And we are just like as a society I mean me we individually but we as a society like it seems okay. This connects to this idea of the devaluation of creative work and I'm going to share a podcast episode actually with you. I'm not sure if anybody here listens to citations needed but they had a great episode last year called AI hype and the disciplining of creative academic and journalistic labour. And it's a fascinating listen for anyone who writes whether academically creatively or journalistically . It's really fascinating

look at the kinds of media language that get used to describe what generative AI is capable of and the ways in which that's being used to police or limit the value of creative work more generally. As I already said, this norm that's changing is the expectation of people to trace the genesis of an idea. I'm on a policy committee right now and it came up in discussion yesterday that well, you can't know where GPT ChatGPT got its information so you can't really expect people to tell you that information. Is that the line we're taking? That's the root we're going down? That seems alarming to me. I'm old-fashioned. I thought we cited our sources around these parts. Then accountability for but also agency over our output. On the one hand we've got computer said this. This is

where GPT spat out so this is my answer. On the other hand we have I created (Audio Gap). >> DR. ALEX KETCHUM: We can't hear you know unless something happened with my own computer. Can you say if you can hear? >> KIT: I can hear you but I can't hear Brenna. >> DR. ALEX KETCHUM: We heard it speed up so can you repeat the last 30 seconds of what you said? We were hearing you and all of a sudden it cut out. >> DR. BRENNA CLARKE GRAY: Among the University internet because I thought it would be better than being at home. I'm going to assume we're going to through expectation of being able to trace the genesis of an idea.

>> DR. ALEX KETCHUM: Yes. >> DR. BRENNA CLARKE GRAY: Accountability for an agency over our output. Just the idea that we expect to be responsible for the things that we write , say and create and that we expect to know what happens to them after the fact. In both cases we're seeing real collapse of that notion. This idea that the computer said this so this is what I wrote down. And I'm not really accountable for that. We see that in policing in the way policing uses AI all the time not to totally change the subject but we do see that as an emergent norm. Then agency over our output like control over what happens to the work that we create. This is a rhetorical question but who benefits from the discourse of inevitability? He

told that all those norms have to shift, that all of the systems of oppression have to be allowed to carry out their work in peace . Who is benefiting from that because it is not normal everyday people. I get it. It's already here. I'm not pretending it's not. But I do think that that doesn't make these conversations unimportant. In fact it makes emergent . It makes principal refusal were appropriate and space to have critical conversations and good information about the risks and harms , it makes that so urgent and instead it feels like we're being invited to ignore all of that and just focus on the cool shiny things that the AI can do. So I promise I'm wrapping up in getting to the end of my time here. I'm not trying to ban generative AI tools.

It would be foolish and also I am philosophically opposed to making choices that turn our classrooms into policed spaces. If I try to ban generative AI tools, I'm asking my faculty to become police and treat learners with suspicion and I'm asking for technologies that as of already said I don't think work very well so that's not where I am. And I can and do acknowledge the potential for good in many of these tools. I'm glad to see the capacity for automatic captioning getting better over time. I'm thrilled to see that alt text is improving just in the last two generations of Microsoft PowerPoint. The alt text it provides for graphics is so much better now than it was. These are all good things. But I do challenge us to think critically and mindfully about when a

technology is worth it. And I think that if we don't have a clear sense of what the risks and harms are and we don't talk openly about that as part of our teaching and learning practice but also just as part of our engagement with the world as we see these technologies proliferate, that we are not going to be able tap those conversations. Because they can happen without an accurate sense of the problems. Here at TRU, we've been developing what we call our critical framework for considering AI. Part of the goal here is to recognise that there are problems

that AI technologies can work to solve. But that there are also potential harms that can be caused. Unfortunately, it is part of the work of selecting a technology or tool to do that work of weighing those harms against the problems that are being solved. We frame this as what's the problem to solve? A question I really like to talk to faculty about is is this a problem of efficiency or problem of learning? Is this a problem that we've created by trying to teach academic writing at scale for example? Or is this a problem of learning that you're trying to help your students solve? Who is harmed by our technologies? And how? Are there ways to mitigate that with this particular technology or is the harm baked in? Who's going to benefit? Is the number one benefactor here a marginalized learner or is it some for-profit ed tech company that we're just funneling public money into? How are we living our values within the institution? How does this fit with our larger statement of who we are? What are the ethical considerations? And it's not that asking these questions makes a decision any easier because I think it makes it harder. But my hope is that it makes it honest. It makes the next step in the conversation more honest. So I am at my time and so will end by saying as we embark on a new era of education I think we really need to think about how our values are represented or not in the tools we choose. As someone who works in

education technology some the first person to say we've done a really bad job of this up to now. But if we are altogether recognising that generative AI represent something of a revolution in our universities and colleges and institutions, then hopefully there's commensurate appetite for change in the processes by which we select tools on the conversations we're link tap about them. So thank you so much for your time today. You are more than welcome to follow up with me by email. My email is there. I'm really grateful for having me today and I'm hoping there's questions and conversation to be had. Thank you. >> DR. ALEX KETCHUM: Thank you so much

Brenna. That was fantastic. I want to welcome you all to type your questions into the Q&A box so that Brenna has the opportunity to answer them. While we're waiting for you all to write in your questions, I want to kind of start us off actually just to set you up for the topic you wanted to give some more time to if it was mentioned in the Q&A which was the way we prompt and how that has an impact on what we find. >> DR. BRENNA CLARKE GRAY: Thank you. I love to talk about this. It's fascinating to me the impact that prompting has and of course there are lots of people who want to tell you that they are prompt specialists and prompt engineers. It's

an emergent field of claimed expertise. We shall see. But I was playing around with trying to see the difference in the way a research question was posed and the outcome of it. So I asked it -- I always pause because I'm never sure if I should say this on a recording. I asked ChatGPT specifically please summarize in 200 words a plagiarism scandal involving Brenna Clarke Gray in 2020. And it gave me this. It was really detailed. A giving examples of where had lifted

work from other people and examples of works I had lifted from. It was not real but never mind that. It was quite a lengthy explanation. So then I prompted it by saying please provide references for the plagiarism scandal involving Brenna Clarke Gray and then it said I don't have any information about that. It's very interesting. I think one of the things that I really encourage people who are choosing to play with this technology to think about is what it means to generate. ChatGPT is not a truth machine. It doesn't have any sense of correctness. What it's doing is giving the next

most likely answer based on its understanding of the question. That means that if I say to a tell me about blah, blah, blah it's going to tell me about that. It doesn't care whether it's telling me about is the truth or not. It's going to look through its data set to find and now I'm not...To find examples of plagiarism scandals. It's going to smoke my name into it

in a bunch of made up text and it's going to have generated a response and it's answering my question. It's telling me about the thing. Whereas when I specifically ask for references then it has to say I don't know what you're talking about. This is the kind of nuance that is really important. It's also like one of those responses is actually libelous, right? If you were

a journalist collecting information and you ran with one of those and you wouldn't because you look and you'd see the books more real but there is huge liabilities here around harm as we've already talked about reputational risk. Those pieces that I think we may be aren't thinking all the right through at this stage. >> DR. ALEX KETCHUM: Thank you. Do you want to read Joe's question and Heidi says congrats on the shift to the research position. >> DR. BRENNA CLARKE GRAY: Thanks Heidi. >> DR. BRENNA CLARKE GRAY: The question from

Joe Reed's I'm frightened by the time factors involved. Students and employees use generative AI tools to be able to produce more stuff. How can faculty members and...To accommodate both approaches? Thank you. >> DR. BRENNA CLARKE GRAY: That such a good question. And I'm not sure that I have the sole answer to it. I think that for most of these kinds

of issues around workload and access and choosing or not choosing to use the technologies and equity around that, I think our goals as institution should be to move towards a practice of disclosure and a practice of transparency around the use of these technologies. And that's a norm that we're seeing . There are good norms emerging too I think. We're seeing Springer came out very early with a statement saying you have to disclose if you use these technologies and know ChatGPT can't beer co-author. It can't take response ability for what you write. But I think that we should all

be moving towards that norm of disclosure because then if that is the case, if it is more efficient or quicker to work with a generative text tool but you have ethical questions about its use and you are opting out, then through the process of disclosure, it would be clear the difference between those two pieces of work. I'm interested in resistance to disclosure policies because to me, resisting disclosing that you're using these tools implies you feel there something wrong with using the tool. So let's talk about that. Let's unpack that further. And I think that that is increasingly the expectation within at least within scholarly publishing that you'll disclose if you've made use of these tools but again these will be emergent norms. We'll see what happens. >> DR. ALEX KETCHUM: Thank you for that response. I want to again encourage people

to type questions. For Brenna to answer. While we are meeting for more questions, I have another one of my own which is about how faculty members can speak to administrators effectively when perhaps some administrators are really excited about certain technologies but faculty members might be wary of the tools or have ethical reasons for resisting like how would you encourage people and faculty members to navigate that? >> DR. BRENNA CLARKE GRAY: That's a really good question. And something that I think here we are getting into power dynamics and what people feel

free to discuss and where they feel free to discuss it and all those kinds of pieces so everybody's position is going to make this different. But I do think something I'm increasingly working on here is tying our choices and practices to our espoused values. In the case of TRU for me the most salient example is that sustainability piece. How does this technology

fit in with our shared goal of sustainability? I'm buying what you're selling. I'm agreeing this is our shared value. Here's my question. I think that can be really helpful. If her no other reason that I'm always asking the question like our our shared values marketing statements or are they shaping budget and practice? That's two different things. I think that can be a really good way to approach things. I also think that ensuring that tools are in line with your provincial privacy laws is really important and that often seems to be a piece that we forget about . And a lot of jurisdictions privacy laws were relaxed during the campus closure period of the pandemic which led awareness of things like freedom of information and prevention protection of privacy to

2024-02-19 19:27