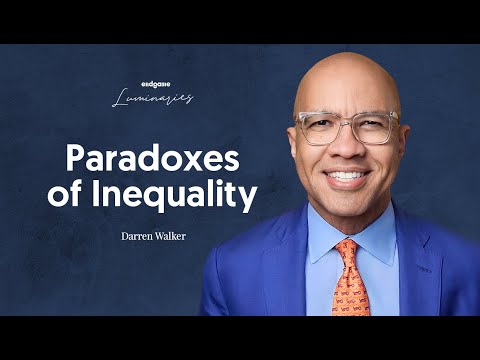

Darren Walker: Justice in the Eyes of the Privileged | Endgame #140 (Luminaries)

There's no doubt that technological innovation has the potential of creating a more unjust, unfair, and unequitable world. But it doesn't have to be that way. Empathy is a critical ingredient to succeed in the world and to also lead and manage in a very complicated changing dynamic world. We have to be able to listen to each other, to build bridges, to find consensus, to find common ground. 80% of the biodiversity in the world is controlled by indigenous people, local communities.

So why aren't we listening to their voices? When you listen to and center the voices of people in this country, for example, who are closest to the communities, and I'm speaking of indigenous people, local communities, they actually can help us solve the problem. They actually provide and can contribute to the solution. Hi friends and fellows. Welcome to this special series of conversations involving personalities coming from a number of campuses, including Stanford University.

The purpose of the series is really to unleash thought-provoking ideas that I think would be of tremendous value to you. I wanna thank you of your support so far, and welcome to this special series. GITA WIRJAWAN: Hi friends, today we're honored to have Darren Walker, who's the President of the Ford Foundation. Darren, thank you so much for visiting us. DARREN WALKER: I'm delighted to be here. Thank you, Gita, for the invitation.

I want to ask you about how you grew up. You were born in Louisiana, spent a lot of your time in Texas, and then how did you end up in philanthropy and how did you end up at the Ford Foundation? Tell us. Well, I was born in a Charity Hospital in a small town in Louisiana to a single mother. I never knew my father, and when I was a toddler, my mother moved my sister and me to a small town in East Texas about 100 miles from Houston. There were 1,200 residents. It was a segregated community because at that time in Liberty County, Texas, black citizens were not allowed to live in certain communities, so we lived in a segregated town called Ames, Texas, in a little shotgun house with no plumbing.

And when I was about five years old, we were standing on the porch of this house on this dirt road, and a young woman approached my mother, who was standing in the front yard, and told her about a new program that President Lyndon Johnson was initiating. The program was called Head Start. It was the first summer of Head Start in 1965. The idea of Head Start, which was funded in part by the Ford Foundation as a research project, was to provide early childhood education for low-income urban and rural boys and girls.

I was in the first class, and it was the beginning of my journey— my love of curiosity. I went to public schools in Texas, and with you share the University of Texas as my alma mater, we are proud Longhorns, Gita? - Yeah. And I was very fortunate after graduating from law school at the University of Texas to be recruited to New York to one of the largest Wall Street law firms, Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton, where I spent time and then left the law to go into banking at UBS (Union Bank of Switzerland). I spent eight years on Wall Street and found myself working in Harlem in the 1990s.

Harlem was a very different place than it is today. And I worked on housing for the poor, economic development, and education, and in that work I came to the attention of the Rockefeller Foundation. I received a phone call one day and found myself in Dr. Gordon Conway, the then president's office, and that was my beginning in philanthropy.

How have you seen philanthropy change? In your book "From Generosity to Justice," you made references to how philanthropy needs to change. But in your experience and within what you have seen throughout history, how do you think philanthropy has changed, and how do you think philanthropy needs to change and could change? Well, we have to understand the history of philanthropy. Certainly in America, Andrew Carnegie in 1889 penned a well-known essay called "The Gospel of Wealth."

And in this essay, he laid out a set of principles to guide the giving of men like himself, and (John D.) Rockefeller, (J.P.) Morgan, (Andrew) Mellon, and others. And his principles were to be charitable, to be generous, and to give back. In fact, Carnegie popularized the notion of giving back. And he, in many ways, was a radical because he believed that everyone should be literate. However, he fully accepted inequality as a phenomenon that was simply natural, and because men like him and Rockefeller were, in his view, endowed with special God-given talents to acquire money, that the only issue for them was how to give it away. Martin Luther King, in a somewhat obscure document in 1968, a few months before he died, said the following about philanthropy: "Philanthropy is commendable, but it shouldn't allow the philanthropist to overlook the economic injustice, which makes philanthropy necessary."

So what Dr. King was saying was something different about philanthropy. He was saying that the work of philanthropy is not just charity and generosity but must be dignity and justice. And that is a different idea, and it requires of the philanthropist a humility, a willingness to understand and interrogate the philanthropist's own complicity in the very problem the philanthropist is now trying to ameliorate. What has changed in philanthropy? I believe today we have a new generation of philanthropists who are justice-oriented, who want to get at the root causes of problems and not simply ameliorate conditions after harm has been done. So I'm excited and encouraged by a growing cadre of philanthropists who are really working towards justice. I'm going to try to rephrase what you alluded to in the book: that charity is sort of like a band-aid canonically, and justice is really remedying the root cause of the injury.

Do you sense that there's enough scale within the philanthropic space that really be able to remedy the root cause of the injury? I believe that the root cause is the greatest barrier to the thinking of philanthropists. And what I mean by that is really engaging in the root cause and so let's be very specific. One of the root causes of the problems we see in the world is racism, is classism, biases towards women and girls, geographic biases, and narratives about certain people or certain parts of the world that are held by powerful and privileged people.

And these are, in large part, the barriers that must be broken through if we are to really get at sustainable change. And so, I know that sounds maybe unrealistic, but it's necessary that we talk about it and that we talk about the culpability of the people who are privileged the most in the very problems. There is an example of a foundation that has a public health focus, and at the very time they were funding a community for improving their public health, they were also investing in the largest polluter in that community. Another example is an American foundation that was working to reform the criminal justice system and at the same time investing in building private prisons. And so, we cannot, without interrogating our own contribution to the very problems that we now want to solve, we cannot solve these problems without looking in the mirror. Those of us like you and me and our friends who are privileged and that we have policies, practices, and cultural narratives that compound the privilege of the already privileged and compound the disadvantage of the already disadvantaged.

Let's talk about inequality. I mean, we have seen how Gini coefficient ratios all across the world; we're not just talking about the undeveloped developing or the developed economies; it's pretty pervasive, and I've sort of been thinking that, to some extent or to a lot of extent, this probably would have been attributable to how money has been a lot more quantitatively eased in recent decades, and how that access to money has been more with the elites, and how welfare and money would have gotten a bit more elitized as of late. Do you see philanthropy as not just a potential remedy to that inequality in the sense of bringing about more welfare for the bottoms of the pyramid but also making sure that the people at the bottom of the pyramid actually would have the needed wisdom and know-how to be able to access whatever money that would have been only accessible to the elites? What's your view on this? Well, let's talk about inequality and democracy, because there is a correlation. In societies where there is growing inequality, democracy is more at risk. Democracy depends on the hopefulness of a society.

I like to say that hope is the oxygen of democracy, and inequality asphyxiates democracy because it provides for elites and privileged the resources, particularly when, as you rightly point out, we've had an era of free money where those of us with access to capital can invest and have had our assets grow at a much father rate than the wages of working people and poor people. And so it's made inequality even more pervasive, and this is why, as you rightly point out, the Gini coefficients around the world are moving farther apart and that is because there is both global inequality and local inequality, and within regions there is inequality. And so we have to take this on. And part of taking it on is for philanthropy to call attention to the harms and consequences of inequality on democracy. At the Ford Foundation, our mission is, in part, to strengthen democracy. We cannot strengthen democracy if we have greater inequality, and it's why we have made fighting inequality our north star; it is our organizing principle.

Part of that as well, as you also rightly point out, is how people at the lowest rows being empowered, being educated, being provided with the resources and tools to lift themselves up and to also demand accountability from we, elites, for our actions that disadvantage them. So, philanthropy has a role to play in both addressing inequality and speaking to philanthropists, but it also has a role to play in helping the poor, the disadvantaged lift themselves up and have their voices heard because low-income people, poor people have voices. We have simply chosen to ignore their voices at our own peril. We kind of talked about this before. If we take a look at the world right now, many of the developed economies that are liberal democracies, they're flush with cash.

Many of us in Southeast Asia, Africa, and some other developing economies, they're genuinely trying to be better democracies, but they're not getting the kind of liquidity that actually many of these developed economies could be helpful with. To the point where it's becoming very difficult for some of us or many of us to try to be better democracies or better liberal democracies. And additionally, I think many of us don't want to just be shackled by the definition of liberal democracy by way of the distribution of power. It also needs to be defined as a way to distribute other essential public goods such as welfare, health care, integrity, moral values, social values, intellect, and all that good stuff. Until and unless that liquidity comes to these sets of countries that are wanting genuinely to be better democracies or better liberal democracies. I don't think it's going to be easy.

I don't think it's going to be fast for these guys to become better liberal democracies. What's your take on this? Well, my take on this begins with understanding the history of development as practiced by countries in the global north, primarily the United States and Europe, who, in some ways with good intentions, I believe, developed a system that certainly helped to lift up people in the global south. There's good news because poverty has been reduced in many countries, but it has persisted in others, while inequality has emerged as a huge challenge.

But we also have to address the bias that exists in the north. How we have created narratives of those people or those countries that seemingly can't fix their own problems when we have contributed to some of those problems. And so while I'm not prepared to release the leaders of countries in the south of their responsibility, I also have to acknowledge that until we are able in the north, to see nations like Indonesia as peers, as long as we hold these decades-old, centuries-old narratives, we will be looking through a very narrow view of the countries. And so, let's talk about Indonesia, which, in my mind, is one of the most exciting, vibrant, and messy democracies. The best of democracies are messy.

It means that people are participating; it means that the citizenry is passionate about their beliefs and their views about their country. And so I believe that the economy here, the economic system, has the foundation to be one of the greatest economies in the world. And the question is, can we bring together the right combination of talent, capital, and a political enabling environment? That doesn't mean it's going to be perfect; it will never be perfect. Look at my own beloved country, the United States of America. We have much work to do after 250 years of still perfecting the idea of democracy. We are far from it.

And our economic system is not delivering the kind of shared prosperity through which the citizenry can feel good and proud about themselves and the country. We've got work to do in America, just as you have work to do here in Indonesia. I want to share with you a little bit of data points. If we take a look at how China would have grown in the last 30 years from a GDP per capita standpoint, they've grown about nine times. We're in Southeast Asia, where Indonesia is, would have grown only about 2.7 times.

I'm actually quite optimistic by way of the progress that we've seen in recent years in sectors such as aviation, marketplaces, and financial services, where we've seen rises of productivity by orders of magnitude; we're talking about four or five X's here. And it just shows to me that if we get our act together in further enriching whatever we've been able to show good progress in and apply that to the other sectors, call it agriculture, education, healthcare, tourism, real estate, energy, and all that stuff, there's no reason for Southeast Asia not to be able to grow at a much higher rate than just 2.7 times in the next 30 years. But there are three or four fundamental reasons as to why we underperform with respect to China. One is obviously infrastructure, or lack thereof. The other is governance/rule of law. The third is education.

If we take a look at the PISA score for most Southeast Asian countries, it's just staring at me that until and unless we get this thing sorted out, we're not going to be able to achieve any of the stuff that you alluded to in terms of perfecting our democratization and perfecting our economic trajectory journey going forward. How do you think Ford (Foundation) could play a part in that, or how do you think you could play a part in seeing the global community become better? We are very proud to have been in Indonesia now for 70 years. And over that time, the foundation has invested in what I call "The Three Is". We've invested in institutions. There are many institutions across Indonesian society that the Ford Foundation played a pivotal role in supporting and helping to create.

There are literally hundreds of Indonesians who have been educated with Ford Foundation scholarships and fellowships because we believe that talent and human capital are the most important resources in the development of a nation and a democracy. And finally, we invest in ideas. The ideas and innovations that make it possible for the economy to thrive, for the humanities and the arts to be a part of one's life, for the rights of all citizens and for women and girls in particular, for rural indigenous people and local communities, which is a major focus for us today.

The empowerment of those communities is an essential part of the democracy, the potential of democracy in Indonesia to be realized. So we see ourselves as a humble and grateful partner, who we are here at the invitation of the Indonesian people. Our objectives are to support the dreams and aspirations of Indonesians.

There are millions of us who are dreaming to have a better future. But what is, at least to me personally, disturbing is that when I used to spend time in the U.S. almost the same time you were at the University of Texas at Austin, we had 16,000 Indonesians studying all across the campuses in the U.S.

in the 80s. That number has dwindled to 8,500. And now we're looking at about 400 to 450,000 Mainland Chinese, about 200,000 Indians, probably about 100 to 150,000 Koreans. Talking about a country that's the third largest democracy in the world, fourth most populous, I like to think we need to be better represented in places like Europe, Japan, China, the United States, Australia, Singapore, what have you, where we can actually attain better educational quality. Not to mention here also, we've got great universities, but we've got to send as many of our citizens all across the world. Don't you think that's pretty surprising that the number has dwindled from 16,000 to 8,500? If it does seem surprising, what do you think we could do collaboratively to help move the needle up? Well, there's no doubt that resources to educate foreign nationals in the United States, for example, have decreased.

There's been a decline in the total adjusted for inflation funds coming from the U.S. government for various programs like the Fulbright program and others. And in fact, philanthropic investments directly in foreign nationals coming to the United States have also declined quite candidly. Part of the reason for that has been the belief that we need to invest in indigenous institutions within countries; that's important.

A part of the reason has been some of the lessons learned from prior programs that regrettably created brain drain situations. So I can give examples where the Ford Foundation supported the education of various people from African countries, from Southeast Asia, and what happened after the degrees were attained in a substantial number, some of the evaluations of our programs, or that they were recruited and retained in the receiving country. And so it's why, for example, a program of the Rockefeller Foundation, the Ford Foundation to train public health professionals, significant numbers of them ended up in the National Health System in the UK, didn't return to Zimbabwe, Botswana, or the other countries. In part because the context in those countries was difficult and challenging to return to. But I want to make sure that I answer your question clearly so that there is no doubt that in order to be a global nation, you must have citizens on the global stage; you must have citizens in global institutions around the world representing your country, representing the very best, the brightest, the aspirations of your nation; and you must also have, within your country, institutions that are of equality and excellence that attract the very best and brightest. And so, our objective is how do we see both of those things happen? I think it's possible.

I'm totally with you in the sense that I'm not in a camp that believes in brain drain. I was talking to a guy the other day, and we started talking about this new concept of brain circulation or brain linkage. And I don't care if an Indonesian gets stuck in Omaha for 20 years; I'm sure that he or she is going to be so value-additive when he or she comes back to the village in Papua after 20 years.

And it's funny; we were talking about the issuance of H-1B visas in the U.S. with the representation of the Chinese at about 400 to 450,000 and the Indians at about 150 to 200,000. Indians make up 75% of the H-1B visa. And that makes me think the Mainland Chinese only get about 10%, the Koreans probably two to three percent. How is it that the Indians have been able to get disproportionately larger percentages than the others were actually much more represented on campuses? I can only come up with an idea that they have this soft skill that accompanies whatever tertiary skills that they would have attained.

If you line up a Mainland Chinese, a Korean, an Indonesian, and an Indian, they're probably equally academically qualified. But for some reason, it's the Indians that can actually project ideas, and I'm at risk here of generalizing or oversimplify, but the fact that they've been able to get 75% of the H-1B visas, I think it's startling, but it's a manifestation of what we need to be doing. Well, there's no doubt that they're in the United States are opportunities for people from around the world, and I think there is no doubt that South Asians and other communities have done very well in the U.S. system. I would hope and understand that first, migration, as it was understood generations ago, has fundamentally changed. Your point is that people are networked today. 50 years ago, when you left a sending country and landed in the United States, for example, as the receiving nation, most people left behind their ties.

Most people came to America to be Americans, to ultimately become citizens, and for the most part, to attain that idea of Americanization assimilation with these narratives of what it is to be an American. I think today, migrants to America very much want to contribute to America, the economy, and the culture, but they also retain an interest in their sending community. And for example, it's one of the reasons why we see groups of immigrant communities forming philanthropic efforts to support the abilities and communities from which they came. And so, I believe that in America we must do better to attract migrants who are interested in coming and contributing to our economic system and making our country, our democracy stronger.

There's no doubt that there is more room for people from Indonesia and that we should have greater representation, and that doesn't come at the expense of any other community. It's simply indicative of the system perpetuating certain practices and affirming certain ways of doing business through a visa system that probably needs some reform. What is your idea of what it means to be educated? My idea of what it means to be educated is that we have a sense of curiosity about the world. And that being educated is actually a mind-opening experience. I often think that people who take very harsh positions, who use very coarse language, and talk about other human beings are not really educated. They certainly are not people who have read great books or enjoyed beautiful poetry or theater or dance, or sitting in front of a great painting.

Because those experiences open the soul and the spirit and allow us to imagine ourselves outside of our own bodies and minds, and it also gives us a sense of empathy. And empathy is a critical ingredient to succeed in the world and to also lead and manage in a very complicated changing dynamic world. So for me, the thing that I worry about is that I see too often people who are "educated" with very closed minds, with deep ideological ideas, and with an unwillingness to listen or hear the views of those we might disagree with.

These are all qualities that are very problematic for democracy. We have to be able to listen to each other, to build bridges, to find consensus, to find common ground. Now, there is no doubt that there are people with whom we should not be negotiating or finding common ground with. But for the most part, I am a believer that education can open the mind. For me, a poor boy from rural Texas, the beginning of my life was when I started to read, and when I could experience Shakespeare and James Baldwin and Zora Neale Hurston and Walt Whitman, and so many others, my mind was open; my life was transformed.

How do we get our kids to read books more as opposed to TikTok and Instagram? Well, I'm not sure that it is about getting them to read books. I think it is about how do we spark their curiosity and their ability to be sustained in one type of learning, or in one book that may be a book that they're reading digitally. But the challenge that I find is that children and young people are presented with the overstimulation that the internet provides and at seemingly infinite amount of stimulation. That means that distraction and a lack of concentration can be fostered. And so, I'm less worried about TikTok being bad or this.

I'm more concerned that the kind of sustained engagement with the subject, with the writer, with an author, with a particular form of knowledge transfer, that is being disrupted because every 15 minutes or 15 seconds there's something that pops up that looks interesting and you've got to click on it. - But, how do you deal with that? How do you remedy that? - Well, there's no doubt that one of the real challenges we have is the ways in which technology unfettered without a policy or regulation can be harmful. And so part of it has to be regulation and policy; part of it has to be in our educational system; and part of it has to be with parents.

One of the real challenges for parents today, particularly middle-class and upper-income parents, is that you want the best for your child. Every parent should want the best for their child. That's admirable.

The challenge is that the pressure that children face from their peers, from advertising, from the ways in which we consume knowledge, information, and data makes it really hard for them to always make good choices. So I do think there's a role for parents to play and the ways in which parents have to simply say, "Of course there's a certain amount of time on the internet that is acceptable, but there's a certain amount that's not," and that negotiation as a parent, I'm sure Gita, you are very familiar with. It took me five years to get my kids to drop their hand phones when we're having a meal. And I didn't want to be like a typical Asian parent. It took persuasions over five years. And now I'm totally cool with having lunches, dinners, or breakfasts with them whenever they're in our home, and I know there's no handphone on a table, and that to me is comforting, but I know there are a lot of them out there that are just continually distracted.

And I want to take this further: we're sort of living in this post-truth era, where feelings are just a lot more important than empirical evidence. And it's sort of like it's correlated with how we're choosing leadership who can actually... or somebody who's trying to attain a position of leadership in a context of how he or she could actually better sensationalize, better festivalize, as opposed to better intellectualize. That is structurally worrying to me because I'm not sure if we're going to be able to assure a future where we're going to have the kinds of really great qualities of leadership like Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi, and all the rest. What's your take on this? My take is that I agree with you.

My diagnosis is a major contributor to this is the internet, the way in which divisive, corrosive language ideas have currency on the internet, and the way in which hate is monetized. We know from understanding the business models of some of the technology companies that engagement and eyeballs are the bottom line. And the quality of the content— the meaning—is less important than the ability to sustain engagement.

And what sustains engagement more is the sensational, the prurient, the often mean-spirited, hateful words and ideas. And so, we have to address that with the responsibility that technology companies should have for understanding the consequences of the information and data on their platforms, and we need to address it with leaders. Leaders who will challenge the divisiveness that swirls around and remind us of the calling of great leaders to build bridges. We have to demand that kind of leadership and reject leadership that seeks to divide us.

We have to own that responsibility. We, the citizenry, and not simply say, "Well, it's all the technology companies' fault," because it's not all their fault. We choose the leaders we get, and we can choose better leaders if we aren't happy with the leaders that we have. Now, that's much harder implementing than my sitting here saying it.

But it must be our aspiration, and this is the idea that we have to mobilize and be inspired by. But what do you think we can do realistically to remedy this root cause of the injury? Because it just seems like a root cause that we're not able to think objectively, we're basing our views and opinions a lot more on feelings as opposed to objective data points or empirical evidence, call it whatever. Because until that gets sorted out, I think we're going to be exposed for quite a while, globally speaking, here.

There is no doubt that this is a complex, layered challenge. Of course, we have to have a policy that addresses it. Of course, we have to have real data and information that gets produced. And then we have to understand why is it that people are susceptible to misinformation and disinformation. Why are they rejecting the facts? Because it is not as if this information is not out there, but many citizens are choosing alternatives to facts and data.

And so that is one of the root causes I want to understand. Why is that? Part of the driver of inequality in this regard is our need for narratives to explain our situation, to justify my anger. And certainly, I can speak from the perspective of the United States, where there's been very good data around understanding why people reject facts and information. It's often because there is an aggrievement there, and that aggrievement comes in the form of economics: "I am more economically vulnerable; why is that?" "Oh, that is because of this immigrant group," or "That is because of some other actions against me and my group." It is the ethnic and tribal sort of affinity that also infects our systems, where we believe that people like us are in some way victims.

And so when presented with data that says, "Actually, you're not a victim, or the reason you are a victim is because of this economic policy." Actually, "No, I'm a victim because of some minority who is doing harm to me." And if you're told that by a political leader or other leader, it is easy to understand the root cause. And I think we have to excavate that reality, which is a reality not just in some countries but in many countries where democracy is at risk. It is at risk.

It's sort of like in a recession right now. And I'm troubled by the fact that more and more people are sort of equating democracy with algorithmic amplification. Until and unless that gets sorted out, we're just going to have to sit by and watch how things go. Well, we're not going to sit by, Gita. We've got work to do.

- We got to do something about it. - We've got a lot of work to do, but part of what we have to do is to remind people that there are reasons for hope. That within our own communities, within our own country, there are exemplars of the very things we would wish we could scale: the ideas, the people, and the institutions working hard to deliver for a better democracy, a better Indonesia, a better world. And so, what people like you and I must do is offer encouragement to those people because, without them, our democracies truly are at risk. I want to jump back to your book. You wrote a chapter about a guy by the name of Chuck Feeney.

I mean, it's so interesting that this guy would do philanthropy until his check bounces. Do you see many people like him? Indeed, there are many people who are spending down their fortune. And I have been impressed of course… - Until actually the last check bounces? - Until the last check bounces.

Certainly, metaphorically, I don't think they will be overdrawn in their account at the bank, but they certainly are seeking to shed themselves of most of their wealth in their lifetime. For example, Mackenzie Benzos Scott. She is an example of a very wealthy woman who has determined that she wants not to die wealthy, and she is giving away billions of dollars every year.

Agnes Gund, the great arts patron, selling paintings off her wall to use the proceeds to reform the criminal justice system. I could go on and on. There are people around the world who very much want to, in their lifetime, make a significant impact towards solving a problem.

And so I'm a great proponent of philanthropic pluralism. The idea that there are all forms and shapes, sizes of philanthropy; you may wish to create a legacy foundation like the Ford Foundation or Rockefeller, that exists into perpetuity, or you may wish during your lifetime to spend it all down. Both of those modalities should be celebrated, and certainly Chuck Feeney is in my book because he is an exemplar of a great spend-down philanthropist. There's another interesting chapter in your book about the poet who basically advocates that in order for you to be able to do philanthropy well, you've got to be able to hold up contradictions, right? I thought that's not only in philanthropy. That's applicable to just about every other dimension.

We live in an era in a world where there are an increasing number of contradictions, increasing number of paradoxes. You've got to be able to hold up in the face of all those, without which you're not going to be able to do well anything you want to do. Well, there's no doubt in the complex world in which we live today, paradoxes and contradictions surround us, and as leaders and managers, we have to be able to hold, sometimes even competing ideas, but certainly ideas that can be at odds. The idea that we want capitalism to thrive has to also be held with the idea that capitalism can also do harm. So for those of us who are capitalists and believe that capitalism is the best way to organize an economy, we want that capitalism to generate shared prosperity, not inequality. But shared prosperity that provides a standard of living, a way of life, so that most citizens are able to live with dignity.

We have to hold a shared understanding, as we do in America, of our history that Thomas Jefferson, one of our founders, was one of the greatest and most brilliant men ever to live. And the ideas that he espoused in our founding documents are some of the most powerful ideas of democracy and governance since Aristotle. We must also hold that he was a racist, that he was an enslaver of other human beings, and that he was unwilling in his lifetime to give them freedom because he benefited economically from their unpaid labor. Both of those are truths that we must hold and not in any way take away from, but to simply understand the complexity of life; the complexity of leadership. But we can do better morally when we hold and understand these contradictions; it doesn't mean that we accept them or that we say we want to perpetuate them.

It simply means that we understand, as the poet Elizabeth Alexander says in my book, the complexity of the human condition and the way in which that manifests, that often can be confounding and difficult to accept. It sort of ties to the observation that for anybody to be a better leader, you got to be more divergent. I mean that sort of allows her or him to be able to anticipate blind spots, be able to manage, mitigate risks that are a lot more systemic or long-term if you can actually show a propensity to manage contradictions because life is not that simple, and divergence, I think, will entail somewhat of a better world with all to hold up or manage things.

And I speak as a former artist. Well, I can tell that you are what I call a synthetic thinker because the divergent thinker is also the synthetic thinker, the person who is able to see horizontally across ideas and disciplines to connect the dots and to understand how to solve a problem. It's usually not going to be one vertical way of thinking, one discipline; the complex world we live in today requires divergent, synthetic, interdisciplinary thinking and leadership to solve problems.

You came up with a list of attributes. Inclusive of got to be humble, got to be sensitive to what you're ignorant of, the privilege of perspective or the perspective of privilege. Would you be able to add anything or any more to that list of stuff that you kind of summed up in your book? It's interesting, I think, the combination of humility and ambition. I have often focused on humility because I think there's not enough of it among wealthy, privileged people. But I also admire the ambition that has often driven people to succeed.

And the calibration of those two human qualities to me, is something I think a lot about. I've got two more topics to cover. Climate change. We kind of casually talked about this earlier.

There's this seeming paradox of climate change or sustainability where on one side, you've got the need to attain carbon neutrality by 2050, which is only 27 years from today. But this only resonates to about maybe 20% of the population of the planet; of course, the other 80% are still worried about putting food on the table, and this is what I call the "narrative of modernization." For countries like India and Indonesia, it'll take them about 90 to 130 years to become modern using the metric of electrification, as for them to go from a thousand kilowatt hours per capita to 5,000 or 6,000 kilowatt hours per capita at the rate that they're only building in India 14,000 megawatts of power generation capabilities per year; Indonesia 3,000 megawatts. These two narratives are just obviously irreconcilable. How do you deal with this contradiction or paradox? Well, I think first we have to be non-ideological about the transition to an economy and a climate system that is based primarily on renewables and the ways in which other forms of energy production can contribute to a better climate.

There is no doubt, though, that many of us who are sitting on the panels at the COP meetings are disconnected from the realities of everyday working poor people around the globe. And I couldn't agree more that we have to think more about them and what their options are, which do not include, as I have in my building and at a nice co-op in Manhattan, a recycling bin through which someone comes and takes it away to recycle. Poor people, people living on the edges economically, do not have the luxury of a recycling bin. They have to eke out a living and try to exist with dignity, and what the Ford Foundation says at the COP26 meeting in Glasgow is not top of mind for them. So I am sensitive to their challenges and their plight, but I also have to say, as we have learned from our work here in Indonesia, that actually when you listen to and center the voices of people in this country, for example, who are closest to the communities, and I'm speaking of indigenous people, local communities, they actually can help us solve the problem.

They actually provide and can contribute to the solution. 80% of the biodiversity in the world is controlled by indigenous people, local communities. So why aren't we listening to their voices? Why aren't they centered in the meetings in Glasgow and other places in Paris? Let's hear what they have to say about how we can get to 2050 or 2080 in a world in which their children and grandchildren can live. I'm actually quite excited about the prospects for an energy transition; a just energy transition; but it's not going to be done without listening to the voices of local people. Are you optimistic that these people are going to be given the opportunity to voice their views, the indigenous? I am very optimistic, and I'm optimistic because I spent time in their communities and time with them and have seen the contributions of foundations like Ford and Packard, the Climate and Land Use Alliance, and others who are contributing to support for their voice.

There was over a billion dollars committed in Glasgow, directed towards these issues. The problem is only one percent of those dollars was actually directed to local people, indigenous peoples, and their issues. And so what we are focused on at Ford is investing in their leadership and their network because they are not only here in Indonesia but they are part of a global movement of indigenous people who are demanding accountability, rightfully demanding accountability for autonomy, authority, and agency over their lands. Last question, Darren. How do you see the role of artificial intelligence? Do you see that as something that you think could be value additive to humanity's effort to transition from generosity to justice? There is no doubt that generative artificial intelligence can be transformational and will be transformational.

I think of it like the Roman god Janus. There are two faces: there is light and there is dark. And from what I see, the light is the potential for AI to provide remarkable solutions in areas of healthcare, transportation, and infrastructure. I also worry that unregulated, unfettered generative AI can simply accelerate, in this digital era, all of the harm of the analog era. So we bring into this incredible world of technology and the internet, and other forms of technology, all of the bad things that we hoped we could leave behind.

And I worry that the power of the individual; our brains, our souls, our spirits are subsumed in technology and that we lose the essence of our humanity. And so I worry about it. I'm hopeful because I do believe that we must continually innovate as a society to solve our problems.

How do we prevent this dystopia? I mean, intuitively, I just think that it could quite easily get out of control, right? And it could actually land a lot more easily and a lot faster in the hands of the elites as opposed to the non-elites. If that were true, it's going to only increase the wedge, and it's only going to undermine our efforts to bring about more justice in every dimension. There's no doubt that technological innovation has the potential of creating a more unjust, unfair, and unequitable world. But it doesn't have to be that way because we can have policies, because we must have some policies.

We cannot, in this sphere of life, have simply unfettered private capital making all the decisions about what is right and wrong, what is permissible, and what is impermissible. The people have to have some say through policy in this regard. We also have to have people like leaders in technology companies who themselves have recently stepped forward to say, "We must pause." This is why the powerful statement that was made by over a hundred of those leaders who said, "We must slow this down in order to understand the potential risks associated with developing generative AI."

So this is encouraging. It doesn't mean that I'm Pollyanna-ish and a believer that "Oh the problem can be solved," but I do believe that we have reasons for hope. Thank you so much, Darren.

- Thank you, Gita. This has been enjoyable. - Enjoy your stay in Indonesia. - How could you not? This is one of the greatest countries in the world. I'm delighted to be here. - Cool Longhorn.

Friends, that was Darren Walker, the President of the Ford Foundation. Thank you.

2023-05-22 18:05