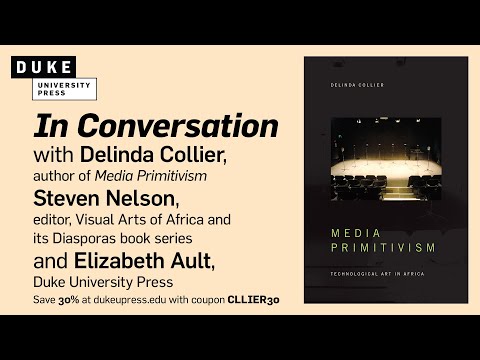

In Conversation: "Media Primitivism" with Delinda Collier, Steven Nelson, and Elizabeth Ault

Elizabeth Ault: Hi everybody, I am Elizabeth Ault, editor here at Duke University Press, and I am absolutely thrilled to be here today with Delinda Collier and Steven Nelson, to discuss Delinda's new book, "Media Primitivism: Technological Art in Africa." Delinda Collier, the author of this fabulous book, is Associate Professor of Art History, Theory and Criticism, and Interim Dean of Graduate Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and Steven Nelson is the Dean of the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art in D.C. With Kellie Jones he co-edits the book series, "The Visual Arts of Africa and its Diasporas," and "Media Primitivism" is the second book to appear in this series. So, thank you

both so much for coming together today to talk about this wonderful book and all of the great work that it's doing! I-- I kind of wanted to start off with just, sort of, talking about the title. It's a little bit of a mouthful, but I think it really gets at some important work the book is doing, and I wonder if you could just tell us a little bit more about that. Delina Collier: Oh, sure. Thank you, thank you so much for

hosting this. Thanks, Steven, for putting it on your list, I'm excited about that. And, Elizabeth, you know I've-- I've expressed to you how grateful I am for-- for the work you did for this book, really. So, media primitivism was a-- kind of a term that I fell onto when I was writing my first book, and so — it doesn't even appear in my first book, but just as an-- as an aside, and - but, as I was writing it, I was like, okay, this is actually-- it's, you know, catchy, but it's also, in a way, getting to what I'm trying to do, which is to braid together three fields: Media Theory and History, African Art History, and Art History, and-- and to get to, kind of, a fundamental understanding of mediation within all three of those fields. So, it's a play on primitivism as we understand it from early-- the early avant-garde-- the historical avant-garde, but, really, also to tie together the moment where these fields diverge and converge in really important ways. And so-- so, yes, it's-- it's talking about the racism implied with primitivism, it's talking about the fascination with origins and substances and, you know, those things that we all kind of participate in at various points, and, you know, to-- to try to expand out that term, "primitivism," but also to use it to check the field of media, which-- which has its own, kind of, unacknowledged history of primitivism.

Steven Nelson: Yeah, this is-- this is terrific, and-- and it-- it-- it provides such a great jumping off point. And-- and we, you know, thank you Elizabeth for bringing us together, and thank you, Delinda, for being here. Thank you for your book! DC: Aww. SN: I mean, yeah, we were-- we were-- Kellie and I were thrilled to include it in this series, because the, you know, the series, "The Arts of Africa and its Diasporas" wants to look at new things, and look at things we already know, differently.

And your book does all of that and more-- DC: Thank you. SN: And so it was-- it was the perfect fit for-- for this series, and so we're-- we're thrilled about it. But, I love-- I-- I want to pick up where-- where-- what-- on a couple of things that you just said, and the one question I had, that you answered, was its relationship to your first book. Because I-- because I read your first book-- DC: Right.

SN: So I was like, wait a minute! She's picking up on information, and running with it, and-- DC: Right. SN: And, sort of, seeing how it plays out in places other than Angola and how it plays out at different moments, different places, and different times. But, what a-- what your book does, and I would love to, sort of, hear you talk a bit about this, is it-- it-- it brings together these three fields through specific objects, and so-- and through specific moments, and through specific histories, and so you know "Yeelen" is one of the-- one, you know, is a wonderful example, because it not only has its own, chapter but then it comes back. It is-- I mean, if there's a star in your book, it is this film, right? DC: Yeah. SN: And-- and-- and rightly.

And so, you-- you go into the object and you look at-- you look at indigenous ways of making sense out of the film, and then you expand it, doing that sort of mix back and forth with, okay this is how we've regarded film, and Africa. This is how the film disrupts that idea. This is racist! You don't say that, but-- but, how did you get to that rhythm, that to-and-fro, that-- that characterizes the whole book? DC: Yeah, you know, that's kind of the the rhythm that I was trying to also get at in the first book, which is to-- to look at particular objects of media because they do, in a way, reside in a non-space. And-- and I think we'll get to that with the cover (I'm pointing to the cover), you know, that-- that media are supposedly outside of cultural specificity, right? And, so, to toggle back and forth between medium and media as they're discussed, both in media theory but also in art history, right, as if they're not culturally marked in some way, but, then, how African art history is always called upon to, sort of, declare its specificity and to-- to be very, you know, kind of, tethered to place, and space, and culture in very specific ways. Ao, I needed that toggling to happen, but it's very complicated to write it, you know-- SN: Yeah, yeah. DC: -- in a way that that doesn't seem like I'm, you know, waffling, or not committing to any one point of view. But instead, what I wanted

to do was was use these objects, and use these artworks, to, sort of, open that space up. It's a space of, you know, the in-between space of media, and this is kind of how I try to frame an introduction, is a space of correlation, and i'm stealing a term from Cécile Fromont, ... you know, where she writes about Kongo Christian Art-- SN: Yes, yes. DC: -- early, early, as a space of correlation, because it's a space where these objects arise in between cultures. And so, you can't say

that film is specific to Europe, or to Africa, or to, you know-- but it is precisely mediating that space. SN: Well, it's mediation, but it's also agency, and it's also ownership, and so-- so in your hands, film-- film is African. DC: Right. SN: And, yeah, film is African DC: Right. SN: And sound is African, technologies are African. DC: As you say, made it African, yes.

SN: People made it their their own thing. But yeah, let's-- you know what-- but-- when-- I want to come back to what you just said, and to the cover image, and to this notion of a non-space. And I would love to hear more about that, and I want to throw in another term as you talk about it, and that's non-object, because, yeah, that's a particular object that you had to write about without being able to experience it-- DC: Right.

SN: -- and possibly not even really being able to see much of it. DC: Right. SN: Right? So, we'd love to hear more. DC: Yeah, so, you know how it is to pick a cover image -- [laughs] and especially to pick a cover image when you work on African topics. There's a lot of,

you know, there's just a lot of things that could go wrong in that choice. So, keeping that in mind, and always having to keep that in mind, I think one of the things that I wanted the cover to do was-- well, first of all, it's-- it's from the staging of an artwork that that I devote a chapter to, "Song of Solomon," and-- and-- but what I found intriguing as an image, an image of a sound work, right, is that it's already gesturing to this impossibility of locating that specificity. And that, you know, as a media artwork that could exist anywhere, you know, but that media was designed precisely to do that, you know, the black box, the theater space, microphones, any-- you know, the way that this whole scene is arranged could be anywhere, because those people who designed those-- those media made it that way, right, they didn't want it to be culturally marked. So, you know-- you know, in a sense, now we can say-- now, you know, part of the work that I'm doing is to say, well, that is actually a very coded cultural space of whiteness, of Blackness, of, you know, the difference between the two. And so-- so that-- so that's one aspect. The second aspect of the choice of the cover was that I wanted to downplay the visual.

And I think, you know, a good part of the book-- half of the book or more is talking about sound, and-- and kind of downplaying ocular centrism as a method of European art. And-- and so, to talk about, also, that history of sound as being, sort of, romanticized as the original of mediation, right, and totally impure without object, you know, like "I'm speaking," and "you hear me," and-- and that kind of pure vibration that a lot of sound connoisseurs talk about. And so, to use sound-- to really test, also, test the ocular centrism of Western art, but also to speak about mediation again as-- in terms of that desire for a primary mediation. SN: Yeah. Well that-- that is so interesting, because as you-- as you talk about that, you know, one of the-- you know one, of the things we could say, right, or if-- you know, from the field, as it were, well what about masquerade? Or what about the griot? Or what about these sort of, like, sound as oral transmission? And-- and-- and your decision not to go there except, you know, in-- in part in-- in "Yeelen"-- DC: Right. SN: -- right, and even there, you're-- you're, kind of, upending this sort of francophone notion of African film as, like, a kind of 20th-century modern griot, which is how it's been characterized. DC: Yeah. SN: So, I'd love to so hear about your decision to, sort of, make those really provocative turns.

DC: Yeah, you know, and I stand on the shoulders of that literature. I want-- SN: Yeah. DC: You know it's not as if I'm trying to undermine that idea of African film as-- as-- as being African because of that notion of the griot. I think that's all built in there. What--

what I'm also trying to add is-- is the fact that that's a content-based proposition. SN: Yeah. DC:That's based on the content of culture, the content of the film, and very rarely looks at the actual apparatus of objects. SN: Right, right. DC: And so-- and Cissé was very-- Souleymane Cissé, the filmmaker of "Yeelen," was very clear about what he was doing in terms of that apparatus, that he was putting the camera, literally, in the space of Africa, knowing that the light would have different effects and qualities there-- SN: Right. DC: --knowing that he could, you know, that a lot of the film that was shipped over would be spoiled by the time it got there because of that. So, he's really carefully thinking of that in a very literal way, so, that's the part that I wanted to account for, in addition to the content-based proposition, which, happens to be, usually, how people identify Africa, and African art. SN: Absolutely, absolutely.

It's the content. It's not the structure, it's not -- DC: Right. SN: It's not the, sort of, discursive field upon which it's playing, you know, especially if that field is not-- not purely African. DC: Exactly. SN: Yeah. DC: Yeah, or, the body of the artist, you

know. SN: Or the body of the artist, right. DC: You know. SN: And, so-- I mean, what you've done, and even that back and forth, when you-- when you do that back and forth, what I think of is that you're taking these-- these objects, or sounds, and looking at them-- you're basically changing the lens. DC: Yeah. SN: And so, it's not, "Gee, I'm sort of leaving this behind so we can talk about 'Yeelen' and nyama," but then you're talking about-- about fetishism, and other things, and, it's not, "Gee, I've switched my topic," it's, "Wait a minute, this film is doing this really interesting back and forth," right? DC: Yes. SN: And so, it's-- it-- it-- is telling

us we are-- it is telling us about itself, that it is telling us about the nature of film. DC: Yes, exactly. SN: I love that. DC: Yeah, and that film is-- it's just remarkable-- SN: Yes. DC: As you know. It's just because what it's doing is also-- I mean, it has the content proposition, too, and this-- you know, his citation of this old Malian, you know, content. But, like I said, that fascination with film itself. SN: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And so-- and so, along those lines--

I mean, you-- you-- you think about-- I-- I love how you think about Africa, and it comes, you know, again, the intersection of the area studies, media studies, and art history, and African art history and anthropology-- DC: Yep. SN: -- and ethnography, and what you-- what comes out, what-- what you produce is a whole bunch of Africas. And so, you know, you've got Africa as location, right, and it is this place, it is this thing that we know, but also, Africa as a set of propositions-- DC: Yeah. SN: -- that trouble the notion of Africa and-- and

trouble, you know, this sort of notion of the fetish. And so, you've moved the fetish from being something that, you know, is African, just into something that is us. DC: Oh, I like that. SN: And-- and I would love

to, sort of, hear you talk a little bit about that process, because you-- you talk about your intro as sort of heavy, and I don't think of it that way. DC: Okay, that's good. SN: I-- I-- I-- or maybe it's because I'm a geek, but I'm geeked out on your intro. But-- but it-- it sets the stage for all of these almost anachronistic, you know. subjects. The

fetish-- is-- you know, at first I thought, this is just anachronistic, this is just weird and interesting, but then it filters through the story that you tell, and I would love to --love to hear you talk about how you weave that through-- through your narrative. DC: Yeah. Well, it's probably not surprising that I wrote the introduction after the rest of the book. SN: We all did. DC: And-- and so what happened is that I was trying to make sense of what I had already written, but also what I was understanding this artwork to be about. And-- and so to do that, I really felt like I had to go back and, just, rethink all of those fields again. Really, it began with me just thinking through: okay, what does... I know that all of these fields use medium in some way. That word,

that term, they use it in radically different ways, and why is this? Why is this? And so, where I wound up as I kind of, you know, went back through all the literature in all of those fields, is to the fetish. It just all went back to the fetish. And so, I know that that was a risky move, and I know that a lot of scholars are unwilling to, kind of, go there anymore, which-- and I totally understand why. And so, as a gesture, as part of that gesture of, kind of, renegotiating the fetish, I really felt like it had to be in order to de-sublimate racism, number one, that that had to be part of the project. And, number two, to get at that exact moment where race, gender, the body-- all of those things become, kind of, excised from discussions of art. And so, when is that? When does that...? You

know, because, in technology studies, there's just-- I think recent literature has started to fix this, but for the longest time, nature and technology were seen as separate. SN: Right, right. DC: That is, race, gender all, of those things were separated out from discussions and seen to be stable because of that, right? Like, that's the stuff that doesn't change. Technology changes. And so, what I wanted

to do with looking at the fetish was say, actually, technology does this work of gendering and racializing, and it does the work of making our bodies rendered into some, you know, some thing, so to recount that history, but also within the terms of, you know, this-- this long history of contact that produces media objects, again, in spaces of correlation, but spaces that become racialized and hierarchized. SN: Yeah, yeah. DC: And so, that had to-- for me, that was the the main, kind of, goal that I had, in terms of intervening into media history, was that it had to stop pretending that it was this neutral-- this neutral space. SN: Yeah. DC: And that it wasn't doing this racializing. SN: And it does the work of making it seem natural.

And so-- and it does a great job of it, doesn't it? DC: Yeah, it really does. SN: And so-- but-- but, you know, going back to this, sort of, history of contact that you mentioned, as, you know, as we've talked about, your book is deceptive. And so-- and I want to talk about that, because-- [laughs] DC: [sarcastically] What?! SN: --in the field. And, you know, part of it is the field, right? And-- and so, we see a book that-- that pretends to modernism, or modernity on the continent, and we think we're going to see a contemporary book, right? And-- and your book, actually, is not what I would call a, sort of, Contemporary African Art Book, with a capital "C," right? It-- it traces really deep, really long histories of technology on the continent, in different places at different moments, and, so, I was just so thrilled when, you know, we're talking about sound and recording in Egypt in the 1930s and 1940s, and even in South Africa, when you're talking about, you know, sound, and Zulu, and things like that, pushing it back. And so, I want to-- I

want to-- I would love to hear you talk about that decision to really give us this, sort of-- these really deep, specific histories of technology on the continent. DC: Yeah, I-- thanks for noticing that. I think, yeah, you know how it is when there seems to be, in the field, and it's, I think lessening now, but, this real firewall between the contemporary and historical in-- when we talk about African art. SN: Right. ... DC: And it seems that we don't know-- or-- or there there was less of a developed field to talk about the contemporary as having a history. And maybe that's true in art history generally, that could be true. But what

I was wanting to do was-- well, it was like a provocation that I had for myself, which is, what would a history of technological art look like if it weren't Western, you know? What would it look like to write a really specific technology history in Africa? And, of course, you know, as I worked back through all those those histories and terms, that's impossible, you know. But it's impossible just generally. It's impossible for European history also. So-- so it is exactly that's-- you know, that fetish, you know, object, but that-- that basic myth or that mis-- mis-perception of the object from the beginning. So, that tracing back of the history, I think, had to happen in order for this book, or this-- this proposition to be compelling at all. And I do think that, going forward, what I would love to see in all of these fields of the contemporary, if-- if we're going to call it that, is this-- is this move to to look at what-- what would that history look like? And even if it's not something that we consider, like, 100 percent, you know locked down, or correct, or not-- you know, there are a lot of poetic gestures in that introduction, too. It's--

it's like a melding together of a lot of things over a long period of time. But the gesture, I think for me, was really important to ground this, in a way that made sense, and-- and almost, in a sense, argued this as a field that's justified, and not just, like "oh, cute, this is, you know, video art in Zimbabwe!" Or, you know-- SN: Right, right. DC: -- so novel, or whatever. Just, I exactly wanted to get away from that idea of novelty, into, like, this has a history, and-- and it's supposed to be there. It's indigenous.

SN: So, then-- so, then, does that-- how did that change the terms for you? So, thinking about getting away from novelty, right, because novelty then means the only way we can talk about video in the Congo is to talk about it as a kind of mimicking of video in the West, which is what we feel-- DC: Exactly. SN: It's-- I'm completely losing the word-- it's-- derivative. DC: Patronizing. Derivative, yeah. This is like a pale imitation of what we see in France. DC: Yes. SN: So, this is a pale imitation of what we see in New York. DC: Yeah, right. SN: And so-- and-- DC: Yeah, and we have to judge it based on those terms, right? SN: Right. DC: And so, if it doesn't look exactly

the way that it does in Paris, or if it doesn't, you know have, the same gallery system as it does in New York, then it's just less quality, less important. We-- you know, you and I know that long history of-- of publications and, you know, scholarly figures [laughs] making such-- SN: Yeah. DC: -- declarations, but yeah. So, that's exactly why. To say this is-- this is the history, and this is how it makes sense, and this is why it's important.

of course, part of that was me just picking the art that I thought was important, and-- and, kind of, building out that history for it. But I think that's exactly-- that's exactly the gesture that I wanted, was to-- was to say that not only-- again, not only that it belongs in Africa, but it has a history that's African, you know, both in terms of that conceptual gesture that you talked about of Africa, but of it being there, just has been there all along, you know? SN: Right. DC: You said earlier, I think before we were recording, you know, five years after photography's invented, it's in Africa. SN: Yeah, yeah, exactly. DC: Not even five years, maybe five minutes. SN: Maybe five minutes! Forty-eight-- DC: It's there! SN: I don't know-- I-- I always told my students it was 48 hours, and I knew I was lying but, I mean they got it. DC: Exactly, right! Yeah, and they

got it. And so, it's not just that it got sent over, but it's also that there was-- there, you know, there was a development of that that technology or that-- SN: Right. DC: -- technological thinking in Africa. SN: Right.

SN: That it got used. DC: Yeah. SN: And it got used in ways that were not mimicry. DC: Right. SN: And then-- and I think that that's one of the-- one of the wonderful takeaways from-- from your-- from your-- from your study. I do want to talk a bit about-- and this is something that Elizabeth is interested in, too, on the role of matter and materiality. DC: Okay. SN: So, as your-- your-- your book discusses that kind of a model ... and that, kind of, an orientation, art and technology, that-- that, related to some of the things we talked about already, is attuned to origins, right? And so, I would love to talk, you know, love to hear more about that orientation for you in the book. DC: Yeah.

Yeah, I think that's-- SN: And the kind of lifting it does. ... DC: It does a lot. SN: Yeah. DC: And there's a lot of ways that that-- that word gets, kind of, taken up in and woven through. I think one of the major themes of the book is mining, and mineral extraction-- SN: Yes. DC: --and that being, of course, a foundational aspect of modernism in Africa-- industrial modernism. But

also-- So, that orientation, which I kind of constantly come back to in the book, of seeing Africa as a-- an unformed natural resource-- SN: Right. DC: -- in order-- precisely in order to exploit it, right? And so, matter and materiality, in terms of how these artists understand that relationship of extraction, and where they, kind of, sit within that history, which is varied, you know, some artists that I talk about are very much part of the exploitive side of that, and some are part of the exploited part of that history, and so they're able to, kind of, present that in different ways. So, there's that aspect of, kind of, that history of material-- the history of Africa as material-- but then also, kind of, what-- what we were discussing earlier is the-- the literal-ness of some of these objects that are being made and used. And the real marking out of the slippage between material, or matter, and the concepts, or the poeticisms, or, you know-- And so, there's also, kind of, a lengthy discussion in the introduction, and throughout, of-- of metaphors. SN: Yes. DC: And, you know, extended uses of literary devices, in order to get precisely to that slippage of how something becomes something else. Just like mining makes, you know, this thing into this other thing.

SN: Yeah. Well, you-- you just reminded me of the-- the-- the threat of allegory that runs throughout your book DC: Yeah. SN: Which I love. DC: Right. SN: I

love, and-- which is-- it-- which-- which, you know, is metaphor, to be sure, but it is-- it is a-- a particular-- particularly inflected kind of metaphor. DC: Right. SN: And so, where-- where-- how was-- how was that working for you, as you were-- as you were-- DC: Yeah, I mean... So, that was also risky to me, like the fetish. It's risky to talk about allegory with ... within the history of the avant-garde, which pretended to totally divorce itself from allegory. SB: Right. DC: Because you had to be literal, you know, and-- and so, what I argue is, not only did allegory never stop-- [laughs] being fetishized in the historical, or in western art, but also that that-- that action of supplanting one thing with another thing is exactly that relationship of slippage that allows artists to rewrite histories, step into histories.

And so it is-- and-- and-- and it can also be, weak and fetishistic, and, you know, be, kind of, used in ways opposite of of the ways that perhaps it was intended. So, there's a lot of risk-- there's risk in me writing about-- but there's also risk in artists, kind of, employing that as a tactic. And, so, I, you know, I had to be willing also to just let that lie, you know, and let it be part of the whole story. SN: Yeah, well, you beautifully took up the challenge of Craig Owens, who [laughs]-- DC: Yeah.

SN: You know, basically-- you know it was-- was talking about this whole allegorical impulse in-- in what he was calling post-modern art in the 80s. DC: Exactly, yeah. SN: So-- but-- but-- and-- and-- I-- I-- I find that fascinating, and-- because because in-- in your book that is, you know, it attunes to content, and I think that we see that in "Yeelen," we see that in some of the other things, "Song of Solomon," but we-- it's also structural. DC: Yeah. SN: The five seconds of light. The five

seconds of light is is a complete allegory for so many things. DC: Right. SN: And, so it's-- it's, you know, about, you know, these different, you know, Malian cultural forms, sort of, mixing and coming together. It's about, you know, film, right? And-- and as you say so beautifully, it's about the, kind of, strand that you're creating.

And so, I'm thinking about light and electricity and nyama, right, that all come together in that moment, and that you-- that you-- you sort of take these threads, and-- and, you know, sort of, show us where they go, and how they emanate, and how they live together. DC: Yeah. SN: Sometimes incongruously. And-- DC: Exactly. SN: And I love that-- that-- that-- your tactic, right? And so-- but I would love for you-- because you-- you did mention this really early on, you know, like, electricity. And I love what you said, you know, at different points, about electricity, and then things that attune to electricity, in addition to the thing itself. DC: Yeah. Yeah, that's probably exactly-- you know, so, in addition to the fetish, that's the other, kind of, thing that's doing a lot of work in the introduction, because that's exactly the relationship that I want to talk about, is-- is, you know, we all-- all of us right now are depending on electricity for nearly everything.

SN: Right. DC: And-- and so, we have even, you know, movies and shows about what happens if that gets cut off. Like, we're all just-- [laughs]. Who knows?! Especially right now! Who knows what would happen. SN: Right, right. DC: We all know that that's there, and that it's a threat if it's gone, but we have-- there's no-- there's very little in the way of a form that it takes that makes it more understandable for us.

And-- and I think that's what John McNaughton, and others who write about nyama-- SN: Yeah, yeah. DC: -- think, you know, they're trying to make this correlation. But-- but electricity, and that kind of, the mo-- moment it becomes more and more abstracted from-- from, you know, the universe, the earth, various materials, the more we get this idea of mediation, right? And-- and, kind of, the more advanced electricity and its objects become, the more advanced our understanding of mediation. And so that was one of the other, kind of, parallel histories that I was trying to write, was, you know, where a lot of people noticed that as soon as electricity becomes really prominent in our cultures in various ways, that's when media as communication becomes more important as a term. Like, the-- the understanding of media as as a communicative device instead of, like, an imitative-- like a painting. It's when we get telephones, it's when we get-- SN: Yes, yeah.

DC:N -- radios, and things that actually are doing mediation on a much big-- much bigger-- a much larger scale geographically. And so-- so, it's definitely a sub-theme in the book. SN: Yeah. DC: It comes into, again, mining in Africa was radically changed once electricity was produced. SN: Right, right. DC: You know, so-- but it's-- but it's very hard to talk about electricity. I really don't even know, you know, when I was trying to write about it I was like, what is this? SN: Yes, yeah.

DC: Like, we all know what it is, but we don't know what it is, really. SN: Yeah, it's like fractions! It's like fractions. You can't talk about it, you can't teach them, you can't-- DC: Right! [laughs] SN: You know, I used to try to teach fractions to fifth graders, and it was not easy, because they-- well, because they were something we just knew. We just take it for granted. It's like the space where you live. Try to get someone to talk about where they live.

DC: Or the taste of salt. SN: Or the taste salt. Or, you know, "tastes like chicken." All: [laughs] DC: Exactly. Yeah, and that's-- that's primitivism, you know. SN: It's primitivism! Everything tastes like chicken! EA: Exactly! That's what I think is so just amazing about this book, is the way that you so deftly weave together these things that are so challenging to wrap your head around, so that you've not only wrapped your own head around them, but you're presenting them and making all these different connections, to allow for, sort of, multiple points of a way into the conversation. And I think

that's also what's really powerful about the arc of the book as a whole, with the different works that you bring in. I mean, I think you were sort of talking about this earlier, too, but all of the different histories that you weave together, moving from Mali, to Kenya, to South Africa, to Egypt, and really-- really, kind of, diving into what each work means in its particular context. SN: Yeah! EA: And I think it's just so powerful, the way that you're able to do that. I guess I was curious if you had

any reflections about that, kind of, the research and writing process of all of that braiding to share. DC: Yeah. It was interesting. The research, in a large way, started as I was finishing my first book. And, you know, I almost ditched my first book to write this one first. SN: I'm glad you didn't. DC: But somebody warned me. SN: For so many reasons! All: [laughs]

DC: For the ten year clause, specifically. Thank you, Sean Smith, for-- yeah. But-- but, yeah, it's-- so-- so, it was-- I have always been interested in what's called "new media art."

That's been something that I've just, long been interested in. SN: I thought that was the book you were going to write. DC: Yeah, exactly. And that was book I set out

to write. SN: Yeah. DC: And then quickly realized I couldn't-- like, I couldn't use that term, "new," because it was problematic. I, you know-- and then-- so each term that I started to pin down was-- was just becoming more slippery. Which is great, I love that,

but it is hard to write. The research, I think, just, kind of, went naturally. Just, some-- some of it happened happenstance, some of it was deliberately researched. A lot of the

artists that I write about I know, and we're friends, and so, kind of, just keeping track of their work. And then, yeah, some really just, fun-- like the best, fun kind of type of research, where you just happen upon something, and then you find out more about it. I think when I was really getting into material, that Wire Magazine article that talks about Halim El-Dabh in Egypt came out, and-- and it was just this big moment, where everybody's like, "Oh my god! Sound art, or electronic music, was invented in Egypt, not France!" You know. [Laughs] EA: Well, the comments on the Youtube video are very contentious. DC: Yeah, exactly.

Right. Yeah, that's not a done story. SN: Yeah. DC: But I was like, well, yeah, what is this about? And-- and why did he, really-- I mean, he never really thought it was that great until much, much later in his life, when he was, you know seeing this other development of a part of his work. So, yeah. But there was a particular challenge I think that you're noticing, Elizabeth, in that all of these-- all of these scenes are very, very specific, and have very specific history, so that part definitely was challenging. And

I constantly felt a little bit like I was imposing in a field that I didn't belong in, right? SN: Which fields? DC: Because we have such deep-- SN: Which fields? I mean, so many of them! DC: Exactly. Like, yeah-- like Congo studies, you know there's a huge literature, and I feel like, you know, that's not my, you know, area. And so, I don't-- you know, I can't really write about this in a way that's-- that's the most informed, right? So that-- but that was part of the whole gesture, for me, was, you know, understanding our legacy, our field legacy of this really deep, thorough, and-- and time-based research that's called "field research," you know, that definitely I didn't do for this book. And, what's the difference

between that type of research, you know, which is also why I put that section in in the introduction about field research and what we think that is. And whether or not-- SN: Well, and it's also-- yeah. I mean, what you did-- didn't say explicitly was that, for so long, the-- at least in the United States, that, sort of, notion of field work was a badge of honor, too. DC: Yeah. Gold standard. SN: That if you didn't do it-- if you didn't do it, you weren't a real Africanist. DC: Exactly. And I think we have yet to have that, kind of, thorough discussion about, not just that, and the implications of what we think a field is, you know-- SN: Yes, yes. DC: -- but--

but also what-- you know, if we can't do that, going forward, what will our field be? And that's the field of African Art History. If we can't get grants to do this anymore, if we-- if nobody has the time to do that anymore. Which, I think I came up in a time where that was radically changing. I was encouraged to, you know, get out within six-- five or six years.

So-- so all kinds of things are really quickly, quickly changing, including, again this apparatus that we're all operating on right now. I can talk to anybody, you know, anywhere, using this very same medium, so-- so what happens to a field in this, kind of, situation? Yeah. EA: Yeah, I mean, I think, in a lot of ways, to me, too, it's part of what makes this sort of an exemplary, like, second book project in some ways. As-- as in, you know, obviously, it's a-- it's a book that you have to have some pretty considerable expertise to write, but that you also have the confidence in the theorization, in the contribution to the field, to not feel like, oh, well I'm not an expert in Congo studies, so therefore I-- I just can't say anything about it. DC: Right. SN: Exactly, exactly. EA: I think in a lot of ways, to me, it seems like a model for this new time, when-- when modes of gathering, and modes of conducting research are radically shifting, for a variety of reasons. DC: Right, yeah.

SN: But also, thinking about, what are the requirements to have something interesting to say about something, right? DC: Exactly! SN: You want to do your homework, to be sure, but, you know, no one's going to expect you to have covered every single thing in-- in Congo studies, or to have lived there. DC: Exactly, right. EA: And, hopefully, it will create lots of interesting continued conversations and debate. SN: Exactly. DC: I hope so, too. I mean, honestly, yeah the field work aspect of that is something I definitely want to keep talking-- I want other people to talk about-- SN: Yeah. DC: How to, you know, what is it-- yeah, what does it mean to-- to-- to be so proximate to your subject, you know, do we want to be proximate to that? Or do we want to be far away from it, so we can see it in a different way? Without, you know, being totally irresponsible, like you said. SN: Right, right.

DC: You know, knowing nothing about something. But, on the other hand, if I just were to walk up to this work and hear it coldly, you know, what would I think? SN: What would you think? And so, I mean-- even with the caption-- I was reading the caption for your cover, and-- and, yeah, the scene is Dublin, and, I was like, wait, what? And you're gonna have people reading this book-- and everyone has to read this book, all right?-- then, who say, wait, what? [Laughs] DC: Right. Yeah, exactly. SN: It's a great puzzle. It's a great puzzle. DC: Yeah. Yeah, and I talked to-- you know, I talked about this work, I think, for one of my tenure presentations, and somebody asked me, like, why are you writing about a white African? SN: Yeah, well there's-- DC: There's another, you know, another question that will come up, I think and, a totally justified one. SN: Well, you've done-- you've done all of these things that, you know, we-- we will never say explicitly, but are, kind of, divides in the field. And so, one of them

is North Africa, right? DC: Yep. SN: Egypt. One of them is writing about white South Africans. DC: Yep. SN: While writing about other people, and not confining it to South Africa. DC: Right.

SN: And so, it's really-- I mean it's incredible. It's incredible. EA: Well, I know you have somewhere to be at the hour, Delinda, so are there any final thoughts? Any way-- things to say to wrap up? Questions from Steven? DC: Just gratitude. Just, thank

you so much, both of you. It's it's a huge privilege to write a book and have people read it. It's just huge. And I'm thrilled that it's done. SN: Well, it's such a great book, and I can't wait to have everyone read it and review it. Yes, here-- read!

EA: Yes. DC: Oh, wait, I have one too! EA: Oh, good. They've got the pens in them, it's dog-eared SN: It's dog eared. I didn't write in it, though. [Laughter] SN: And no post-its, no post-its in books. EA: Not an archival medium!

EA: Well, thanks so much to you both, this was really lovely. SN: Thank you! DC: Thank you, yeah. SN: Thank you, Delinda. Thank you, Elizabeth, this was terrific. DC: This was. Thank you so much, really. SN: Thank you so much, and thanks everyone for watching.

2020-12-30 15:19