R:ETRO webinar – A structural injustice approach to business ethics

Hello everyone, and welcome to the final R:ETRO seminar of this term. My name is Rita Mota and I'm the Intesa Sanpaolo Research Fellow at the Oxford University Centre for Corporate Reputation. With me today is Alan Morrison, Professor of Law and Finance here at the Saïd Business School in Oxford, who co-convenes R:ETRO with me, and our guest speaker, Harry van Buren. Harry is the Barbara and David A. Koch Endowed Chair of Business Ethics at the University of St. Thomas'

Opus College of Business and an Honorary Professor at the Queen's University Belfast School of Law. He is an expert on business ethics and his research focuses on relational stakeholder theory, business and human rights, human trafficking in global supply chains, feminist theory, and employment ethics. Harry has published extremely important work on all of these topics. And he's actively involved in the business ethics community as a section editor for the Journal of Business Ethics, a member of Business & Society's editorial board, and a fellow of the International Association for Business & Society.

As you can probably tell, I am absolutely delighted to have Harry here today and I'll turn the floor over to him in a moment, but before I do so let me say a few quick words about the seminar. Many of you are regular attendees, and so you've heard much of this before, but for those of you who are here for the first time, let me give you some context. R:ETRO, that is Reputation: Ethics, Trust, and Relationships at Oxford, is a seminar series that is concerned with the ethical and normative content of trust and reputation in organisational life. The seminar

series started in January, 2020, moved online when the pandemic made in-person events impossible, and has been generously supported by the Centre for Corporate Reputation since the beginning. Although many academic events are now back to an in-person format, Alan and I have decided to keep R:ETRO online because this is the best way to continue to include people from all over the world. It is undeniable that having such a wonderfully diverse group of people in the virtual room makes for much more stimulating and wide ranging discussions, so thank you for coming and for being part of this community. And I would also like to thank the people who make R:ETRO possible. Rupert Younger, director of the CCR, who's always been supportive of this series in every possible way. Hannah Cooper, Chris Page, Mark Hughes-Morgan, and Dariusz Dziala who do all of the essential backstage work to make these seminars happen, and of course, Alan, whose knowledge and wisdom have been crucial to the existence and success of the series. Today's seminar addresses the very important question of whether businesses should bear responsibility for harmed stakeholders that results from structural injustice. This is a

difficult question because we commonly think about business responsibility in terms of a particular organization's deliberate choices and not so much in terms of how they benefit from injustices that result from social norms, institutional processes, and legal frameworks. In recent years, we have witnessed growing calls for businesses to address structural problems such as gender or racial discrimination, but at the same time, it doesn't sound reasonable to expect any one corporation to fix all of the many structural injustices that happen around it. And in reality, some businesses have even suffered public backlash for engaging with this type of problem.

Are businesses responsible in these contexts? If so, to what extent are they complicit if they decide to be bystanders in the face of systemic discrimination, domination, and deprivation? It's easy to see that we need to understand these questions, but much harder to answer them. I'm very much looking forward to hearing what Harry has to say, and I'm sure that we'll all have a lot of questions to ask him after his presentation. Harry will speak for around 20 to 30 minutes, and after that we will have some time for questions and answers. Most of you already know how this works. Please enter your questions and comments into the Q and A box, not the chat, and either Alan or I will relay them to Harry. You can find the Q and A button either

at the top or the bottom of your screen, depending on the device that you are using. We're going to finish promptly at 5:00 PM. Harry, thank you so much for being here today. The floor is yours. Thank you very much, Rita for the kind invitation to participate in this seminar series. Thank you to Alan and everybody at the Oxford Centre for Corporate Reputation. As we've been in the pandemic conditions now entering into our third year, we've all had to develop new ways of exchanging information and talking about ideas, and this series I think has been a brilliant exemplar of what can be done in that regard. The title of my presentation, as Rita indicated,

is A Structural Injustice Approach to Business Ethics. And I'm going to give you a sense of the flow of the ideas in the presentation, which will occur in three parts. The first is I wanted to give a definition of structural injustice in two examples which have different sorts of nexuses to business behaviour. I'll then move to the thorny question of voluntariness and complicity

in business ethics, and I'll conclude the presentation by giving what I hope is an outline to what a structural injustice approach the business ethics would look like. Let me start with a definition and to examples. And throughout this presentation, I'm going to be drawing heavily on the work of the late Iris Marion Young, who is one of my professors at the University of Pittsburgh. And Iris did incredible work in political philosophy, a lot of which really does have modern day implications for the work that we all do as business ethicists. I'm going to start by reading this definition, because it will underpin everything that I say in the presentation.

Young defines structural injustice in this way. Structural injustice exists when social processes put large categories of persons under a systematic threat of domination or deprivation of the means to develop and exercise their capacities, at the same time as these processes enable others to dominate or have a wide range of opportunities for developing and exercising their capacities. Structural injustice is a kind of moral wrong distinct from the wrongful action of an individual agent or the wilfully repressive policies of a state. Structural injustice occurs as a consequence of many individuals and institutions acting in pursuit of their particular goals and interest within given institutional rules and accepted norms. And embedded in this definition are many of the themes that Rita reflected on in her introduction, and which I will be exploring during this presentation. To move from this definition of structural injustice,

let me give you two contemporary examples that I've been thinking a lot about as ways of trying to express what structural injustice is getting at, but then more importantly, in this context, its relationship to business. Before I do that, I actually want to briefly outline how we know if someone is suffering an injustice. We can ask a series of questions. We can ask, for example, is a person suffering involuntary harm? Sometimes people will suffer harm, but maybe they've engaged in some sort of informed consent. If a person is suffering involuntary harm, that's a sign that they may be suffering in injustice. If the harm is being suffered by someone else, would you be willing to suffer this harm yourself? Think of this as a convenient perspective on injustice. And third, and this will be an idea that gets weaved throughout the presentation, does everyone involved have equal opportunity to achieve what they want to achieve? And with that as a backdrop, let me move to two contemporary examples of structural injustice. Many of you have

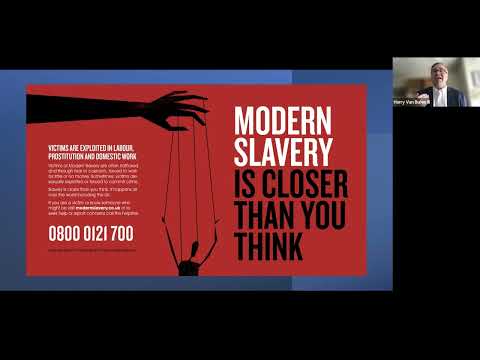

heard the term period poverty, period equity, period justice. The core idea behind period poverty is that for girls and women who menstruate and other people who menstruate as well, these products are often extremely expensive, particularly relative to their income, and they may lack access to these materials. Here I have a couple of pictures from different campaigns that are dealing with the issue of period poverty. And last week, when I was in Belfast in Dublin, there were a number of initiatives that were being talked about related to this particular issue. The second structural injustice I want to talk about is modern slavery, where I have been doing a lot of thinking, along with many other folks in the business ethics field. And this is also from a campaign in the UK. The core idea behind modern slavery is trying to look at exploitative labour conditions. This

often gets wrapped up in conversations about human trafficking, but modern slavery really reflects the broad range of employment relationships in which there is severe exploitation of workers. Let me talk about period poverty as a structural injustice, reflecting on the causes of it. Obviously period poverty has poverty embedded in it, so we can look at poverty and its causes.

Obviously low wage work is a significant cause. In many places around the world, people who menstruate do not earn enough to be able to afford menstruation-related products. Related to this can be a lack of government support for menstruating people. Behind all of this is stigmatisation of menstruation, which is a longstanding historical condition, but it continues to the present day, and indeed, one of the real barriers until recently to dealing with period poverty is the fact that menstruation is stigmatised and seen as shameful as opposed to a basic biological process. Further underpinning period poverty is oppression of women, whether we're talking about biological women or identifying women. And what's the nexus of business? Here I would note that

the nexus of business is largely indirect, so low pay for some employees who need to purchase these products. That can be one cause of period poverty as a structural injustice. Now, to go back to the definition that I used from Young, period poverty is not a construction of any one party, it's not embedded in law. Rather, it comes out of a complex set of historical and cultural law circumstances that also have economic dimensions and at least have some indirect nexus to business. Now, if I move to modern slavery, obviously that's a much more direct nexus of to our business, and I'll come back to this at the end, when I talk about the role of business strategy in modern slavery. But what you see from these bullet points is a very similar sort of analysis. Poverty and its causes, causes people who are desperate to improve their circumstances to seek out employment, and in so doing, they become enmeshed and victimised by people who perpetrate modern slavery. You also have just broader stigmatisation and oppression

of victims and people at risk of becoming victims. There's a robust literature in labour economics, for example, looking at who is more at risk of becoming enmeshed and victimised by modernised slavery, and it tends to be people who have minority status in their countries of origin, who may be political opponents or members of ethnic and racial groups. The nexus of business is obviously more direct, even through myriad supply chain layers and relationships. What do period poverty and modern slavery have in common? Building on Young's definition of structural injustice, I think there are a number of commonalities, so they advantage some people while disadvantaging others. In the case of period poverty, it's women, identifying and otherwise, who are disadvantaged and menstruating people.

With modern slavery, the people who are advantage are people like us, people who buy products for lower costs than would be otherwise the case if the products were made in truly safe and just conditions. There's advantaging of some people in disadvantage of others. Both arise out of social conditions in which some people are victimised, dominated and deprived, whether on the basis of gender or whether they're menstruating or whether they're just favoured or in poverty in some sort of way. Some people are being victimised, dominated and deprived, and they're being victimised, dominated and deprived because of complex and localised conditions, including laws, but laws are only a small part of the equation. We have institutional processes and social norms and customs. Menstruation, for example,

has been stigmatised for thousands of years. People who are victimised in modern slavery are victimised often because they come from a context in which their membership in one or more groups makes them vulnerable to mistreatment. However, and this is a key point that I'll come back to, no single actor brought them about or sustains their persistence. It's not like somebody developed a system in which period poverty exists in a particular place, or that developed modern slavery as some sort of localised economic strategy. So no one single actor brings them apart, brings them about, or sustains their persistence, and that obviously makes them more pernicious and makes it more difficult to figure out causality and responsibility. And in different ways, both of these have a nexus to business,

and I'll come back to both of these at the end of the webinar. And in a early paper looking at structural injustice, Young wrote this. When we judge that structural injustice exists, we are saying that at least some of the accepted background conditions of action are morally unacceptable. And I think that also underpins both period and modern slavery. There

are basic background conditions that business has a nexus to, and those background conditions are morally unacceptable, and it's the background conditions that sustain the structural injustice. I want to move from that to the topic of voluntariness and complicity is ethics, which as the people in the webinar know, is one of the really, really thorny issues in our field, because it really gets to questions of who is responsible, who ought to act, and how should different parties with responsibility to act should act? And what I want to want to do is I want to contrast two stylized stories about unethical business behaviour, and let me start with a very simple story about unethical business behaviour, and it goes something like this. A business seeks to advance its interests by intentionally harming one or more stakeholder groups, and it builds its strategy around that impulse. And probably a really interesting way to reflect on this is through a Cartoon from Dilbert. And so the middle panel depicts the company's new business strategy, we abuse our employees and pass the savings onto you. And I think that's a good exemplar of this simple story about unethical business behaviour, where a company decides that it's going to exploit employees and make itself better off by making customers better off. Now, that simple story does explain

some business behaviour, but let's make things a little bit more complicated and tell a more complicated story. Let's start with the proposition that in advancing its interest, a business undertakes actions that harm one or more stakeholder groups. Now, sometimes these harms can be intended. They can have something in common with the simple story, but sometimes they happen because the groups that are being harmed are at a disadvantage due to the existence of structural injustices, but the businesses don't necessarily intend to cause harm. Now, the issue of intent is problematic and it's something I'll come back to because I think this is an area where structural injustice offers some real opportunities to reflect upon the responsibilities of business. Now, we can look at some contributing factors as well. We can look at issues related to power and effective voice. Generally speaking,

stakeholders that lack power and effective voice are more likely to be exploited, and of course, there is a long line of research probing these very questions. What do both of these stories have in common? Well, I think they have two things in common. First, there's some element of externalising cost to stakeholders. Another test that we can

apply to whether somebody is being exploited is whether they are suffering negative externalities, so pollution of course, the clear example of this, but there are certainly other examples we could look at as well. What are unsafe working conditions after all, but a kind of inflicting of an externality onto vulnerable workers? The notion of externality, I think, is really important in business ethics in general, and it's something that both the simple and more complicated stories have in common. Second, we can look at unjust structural conditions that bring about diminished stakeholder power and voice, which then leads the worse outcomes for them. Going back to Young's original definition of structural injustice, there is this very strong element that some people are being advantaged and other people are being disadvantaged, and the people that are being disadvantaged are disadvantaged because of underlying unjust structural conditions. And this brings me to the thorny question of business culpability,

and in some sense, I think we like to tell simple stories about business responsibility. Bad actor intends to do a bad thing to somebody else, bad thing happens and we can draw a straight line between business intent, business action and a bad business outcome. But in the more complicated story where we have to reflect on underlying conditions that are unjust, I think the structural injustice perspective adds to something that's really important. The first thing is that it focused on the effects of business behaviour, as opposed to business processes. Going back to work that Donna Wood did on corporate social performance, one of the things that I think the field of business ethics has not focused on nearly enough are outcomes that are experienced by stakeholders. And obviously part of the reason for

that is outcomes are really difficult to measure, and it's difficult conceptually to draw a set of relationships between intent and business actions and outcomes, or even just business actions and outcomes. But a structural injustice perspective, as I'll come back to, focuses on effects of business behaviour. Are people being harmed or are they receiving benefit in some sort of way? And I think this is a more important question than business intent or business processes. Now, I think it's important to note here that I'm not giving up entirely on business intent. Businesses can intend to engage in harm, and after all, the simple stories sometimes does have an element of truth to it. I would argue that it's probably less important than looking at the

effects of business behaviour. And similarly, business processes. I think a lot of times academic work in business ethics focuses on business processes, and the reason for this is business processes are easier to assess, it's easier to get data on, but looking at effects of business behaviour and who is experiencing those effects is obviously significantly more challenging. I'll come back to this when I look at business culpability in terms of effects of business behaviour for people who are being negatively affected by structural injustice. A related question, and one that often comes up a lot in analyses of business ethics, is foreseeability in stakeholder harm. And I want to start with the last point and then work my way back up to the top of the slide. I would argue that in 2022 things have moved on in a number of ways to a point where I think it's just implausible for businesses to say that their strategies and their behaviours are not harming stakeholders, particularly when we think about things like supply chain relationships. Woeful ignorance is

itself a kind of intentional harm, and more to the point, I think a structural injustice perspective is more demanding of managers. It demands that managers think more deeply about their strategies and how those strategies affect vulnerable stakeholders who are being victimised by structural injustice. Now, moving to the first sentence, I would also notice that these harms to stakeholders may be foreseeable in various degrees by the businesses involved, and so I think we can draw distinctions between direct and indirect harm, but the more important point is the second point, that the harms occur because behaviours and strategies interact with stakeholder vulnerability brought about by the existence of structural injustice.

And this to me is really where the heart of the matter is related to business culpability, how business behaviours interact with stakeholder vulnerability, facilitated by the existence of structural injustice. And it's a point I'll come back to in the last part of the presentation. And so if we draw a relationship between structural injustice and business practise, the nexus between business and structural injustice is organisational policy and practise, whether undertaken by individual businesses or by businesses working collectively. And I think this is also a really important point, so if we go back to the definition of structural injustice that Young offered, one of the points that Young makes in this definition in her work in this domain is that no one party creates a structural injustice, so by definition, no one party can solve the injustice. And here I want to close this section with another quote from Young, which I think really starts to get at both the analysis of structural injustice, and in some sense, it's nexus to business ethics. And she notes in her 2006 paper on responsibility in global labour justice that, quote, our actions are conditioned by and contribute to institutions that affect distant others, and their actions contribute to the operation of institutions that affect us. Even when we are not conscious of, or when we actively deny a moral relationship to these other people, to the extent that our actions depend on the assumption that distant others are doing certain things, we have obligations of justice in relation to them.

And the points that I really want to lift out from this quote are the middle part after the ellipsis. Even when we are not conscious of, or even when we actively deny a moral relationship to these other people. And what a structural injustice analysis says is that relationship exists, whether you're conscious of it or not, whether you even disclaim or deny that relationship or not. The fact is the

relationship in which action is occurring in which structural injustice is embedded, that's what creates a moral obligation, and it creates a moral obligation both for individual firms and for firms acting and behaving collectively. And now I want to move to the last section, which is what I'm calling a structural and justice approach to business ethics. And a couple of quotes from Young's work here that will underpin the analysis in this section. The first really gets at the thorny question of responsibility, and in Young's work on global labour justice, including work on sweat shops, she drew a distinction between a debt-oriented analysis and a result-oriented analysis of responsibility. And so she knows that responsibility doesn't reckon debts, but aims the results, and thus depends on the actions of everyone who is in a position to contribute to those results. And then in the 2006 paper on global labour justice, the social connection model of responsibility says that all agents who contribute by their actions to the structural processes that produce injustice have responsibilities to work to remedy these injustices.

Here you see the clear attribution of responsibility that moves away from a debt-oriented model or an intent-oriented model, or even a model focusing on business processes toward results and those that are contributing to the continued existence of a structural injustice, and also those who benefit from the structural injustice's existence. I think there are three distinctives of a structural injustice approach to business ethics. The first is that there's a strong focus on measuring outcomes as experienced by stakeholders rather than business processes. And this is a point that I come back to over and over again, because I think it does really represent where a lot of work in business ethics needs to go. Whether it's work in business and human rights, or corporate social responsibility, we tend to be very good at measuring processes, whether it's codes of conduct or membership in multi-stakeholder initiatives or any number of other things. We're good at processes, and we're good at inputs. It's much harder to measure outcomes and then to draw a relationship between processes and inputs and outputs as experienced by stakeholders. But ultimately from a stakeholder perspective,

what really matters is the outcome. Are they better off as a result of the business's action? Second distinctive of the structural injustice approach of business ethics is the necessity of ethical reflection on the ways that business strategies benefit from and sustain instructional injustices, and a big part of this is the last part of the second point, which in turn makes it invisible visible to managers. think one of the real distinctives of Young's analysis, and of a structural injustice approach in general, is it really forces managers, I think, to look at their business strategies. The business strategies themselves, they may think of as morally neutral in not contributing to the structural injustice, but looking deeper at the strategies, and particularly as they affect vulnerable stakeholders, may make visible things that they hadn't thought very much about. And this really gets into an analysis of plausible and implausible deniability. And I think what a structural injustice perspective really forces managers to think about is, what are they not seeing? What are the logical, approximate and obvious results of business strategies? For example, if a business is engaged in a supply chain strategy that focuses on reducing costs and reducing costs and reducing costs, the business doesn't then get to pretend to be surprised if at some link in the supply or value chain there's modern slavery. That was an entirely foreseeable,

or should have been a foreseeable element of that strategy, and then analyses of business responsibility that are forward-looking and focus on whether businesses can help remedy structural injustices to which they are connected. And I think these three distinctives of a structural injustice approach really then start to impact the nature and content of business responsibility in an interesting sort of way. Let me return to the two cases of structural injustice I talked about earlier, period poverty and modern slavery. And here I just want to add

just a couple of points here. Let me start with the last point of, if we think about localised period poverty in a particular context, we can view that as a signal of structural injustice, so if you're operating in a location in which period poverty is endemic, that's probably a sign that you're operating in a context in which women and people who menstruate are being discriminated against in some sort of way. Now, let me double back to the first two points, what are some concrete process things that businesses can do, and then let me talk about this in terms of outcomes. Well, one thing that a business can do is to make period-related products available to menstruating employees and take other actions that would make workplaces period-friendly. And I think that's a very

concrete action. It's an input that businesses can do to take action on period poverty. They can also partner with other businesses to make period-related products widely available where they are scarce and costly. Now, these are inputs, but what really matters is to what extent does business action on period poverty, which is a growing area of action for a business, to what extent is it actually reducing period poverty? And so here businesses could look at outcomes such as, are there fewer women who lack access to menstruation-related products? Are fewer menstruating employees missing work or missing school? Here we can look at business action on period poverty as both a diagnosis of structural injustice on the basis of gender, look at particular actions that businesses can undertake, and then really think about this in terms of what are the concrete outcomes that businesses can measure to really figure out if they're making a difference related to the structural injustice of period poverty? And then to look at business action on modern slavery, this typology comes from a paper published in Business & Society with my co-authors Judith Schrempf-Stirling and Michelle Westermann-Behaylo. In here what we do is we look at a couple of different dimensions

of modern slavery and human trafficking. Does the business have a strong or weak connection to modern slavery, and is there a high or low collective ability to remedy and respond to the problem of modern slavery? And in each box of the typology, there are different business strategies that can be undertaken. Let's say a business has a strong connection to modern slavery, but the business doesn't really have a lot of partners to work with. That could be the Ikea example where the business realises the only way that it can deal with the structural injustice of modern slavery is to vertically integrate its operations.

And then the other elements of the typology, high or strong connection to human trafficking, high collective ability. This would be where suppliers would work together to set minimum standards. The gap in other companies are an example of this. Weak connection and high collective ability. You have a lot of groups that are really interested in this issue and have high ability to respond to, in some sort of way, but they have a weak connection, and this is where we see the growth of organisations such as the Global Business Coalition Against Human Trafficking. But then even businesses that have low collective ability, low connection to modern

slavery, UPS would be an example of a company that did things like train drivers to recognise when they were delivering packages to businesses in which modern slavery may be occurring. What we do in this particular paper is we draw on ideas from structural injustice, we look at a couple of different dimensions that help us understand the nature of business responsibility, and then we offer different ideas for what businesses can do concretely to contribute to ameliorating the structural injustice of modern slavery. But again, the point that I made about outcomes is something that's really important to think about here because one of the very hardest things to measure in this domain is the relationship between business actions and the reduced incidents of modern slavery. And so I think this really leads to three implications of a structural injustice approach to business ethics. The first is really focusing on measuring outcomes and impacts as experienced by stakeholders rather than business processes. And this, I think, really is a fundamental issue to think about in this regard. How do we reorient our research as business ethicists to look at

what stakeholders are experiencing, how negative outcomes are approximately related to externalities and structural injustice, and how do we focus on outcomes and impacts rather than measuring the easier thing, which are business and inputs? This also relates to the necessity of collective action, as well as action by individual firms. So yes, there are going to be actions that individual firms can undertake to alleviate a particular structural injustice. However, it's more likely the case that there's going to be a need for collective action among different firms in order to remedy the structural injustice.

Again, if no one party created the structural injustice, no one party on its own can solve the injustice. And then finally, to the extent that structural injustice are sustained by power imbalances and diminished stakeholder voice, what are the things that businesses can do to legitimise and strengthen institutions that support the exercise of stakeholder voice and reduce these power imbalances? What I hope I've been able to sketch out is an approach to business ethics that first moves the conversation away from the actions of individual firms and toward the social and economic system in which businesses formulate and execute their strategies. Really, reorienting the conversation and getting all of us as business ethics scholars, but also managers to really interrogate the extent to which their business strategies are benefiting from, dependent on, and contributing to the existence of structural injustice. Second, I think analyses of business ethics structure and structural injustices shift the conversation away from individualised blame, and in some sense away from blame itself. It's not that blame is a bad thing or not useful in the context of business ethics. It's probably less helpful than really thinking through what can we do together to alleviate these structural injustices? And then finally, away from measuring processes and toward measuring and ultimately improving outcomes and impacts for all stakeholders.

And with that, I will stop there and look forward to your questions. Thanks, Harry. That was fascinating, and thank you so much for making such a complex, difficult topic sounds so clear and intelligible. That's just incredible. Thank you very much. Let me just remind the people in the audience that they should put their questions and comments into the Q and A box, and I will be going through them and relaying them to Harry. And I have a lot of questions, but because I can already see that the audience is already putting quite a lot of questions into the Q and A as well, I think I'll combine one of my own with one from the audience.

Just playing devil's advocate, because I agree with essentially everything you said, but... And this is a question that I know comes up a lot when people talk, for example, about positive human rights obligations and things like that. I can see how you can make a very strong case for business intervention in countries where, for example, you have essentially failed state that is not protecting its citizens, not really doing enough to make sure that they have the basic conditions to develop their capacities and all that. But if you think about countries where that's not the case, and if you think of situations that are a little bit more complex than, for example, just giving away products or services to people who need them, that might require some sort of intervention that affects the political and potentially legal balance in that country, how do you deal with questions about the lack of democratic legitimacy of businesses to deal with those issues? And there's a related question in the Q and A here from Athel Williams that I think is a bit like the reverse of the coin, and he's asking about the fact that you can view companies as social institutions that deliver social good, and society licences this behaviour and grants the firm legitimacy to perform an economic purpose. And this means that the firm's resources and capabilities are to be geared toward its economic mandate, so why should a firm divert resources from its economic mandate to address ills of society? This really, I think, relates to the contours of responsibility in different sorts of places, and it's one thing to think about this in a place with legitimate government where public policy broadly represents the will of the public, as opposed to different sorts of contexts where businesses really can, for example, inflict externalities, harms to various stakeholders. I would argue in that sort of case, that's where structural injustice analysis becomes really, really important, because those are the context where businesses have a lot of degrees of freedom to behave as they see fit, to inflict harms on others, and that's where businesses really need to interrogate their business strategies much more strongly. Now, related to the second question... Can you restate the second question?

Sure. It was about the fact that it's possible to view a firm as having an economic mandate that's granted by society, and whether it would be legitimate for a firm to divert resources from that economic mandate to this mission of addressing structural injustice. Yeah. And that's a question that of course we get all the time in the context of business ethics. A couple of things I would note here. One is I'm obviously making a particular normative claim related to responsibility, and in some sense saying that even if a business can benefit from a structural injustice, it ought not to do so. In some sense, a structural injustice analysis

really proposes a moral minimum on firms, and the broader question about the legitimacy of diverting or using business resources that are away from the economic mission and towards remedying structural injustices, in some sense, I feel like the conversation has just moved on, in that regard. And part of it is that stakeholders are obviously expecting more of businesses, and increasingly I think that a lot of the analyses of activist groups and civil society are either explicitly or implicitly drawing on analyses of structural injustice. I think this really represents an evolution in the normative conversation about business responsibility, and ultimately it really does relate to how do businesses respond to moral minimums? A big part of what I'm trying to do in this particular project is to think about the moral minimums of business in a different sort of way. great, thank you Alan. Thanks, Rita. And thank you Harry for a really totally fascinating talk. I really enjoyed that. And I have an awful lot of questions,

as does the audience, so I'm going to roll my question into questions that come from Joel Harmon and Judith Schrempf-Stirling, who had questions that touched on what I'm concerned with. And I wanted to understand an implementation question, or essentially two implementation questions. One is... Oh, so one implementation question is when we focus on outcomes, does that mean that we leave the structural injustice in place? Suppose that I employ a great many people who menstruate and many of them are very poor and I provide them with products that will address their period poverty. The structural injustice is still out there. In fact, I might even be making it worse because I have deep pockets, hypothetically. Perhaps the people who make the relevant products can just take advantage of me because maybe their business model is to do so, that Joel Harmon's point. And relatedly, it's a structural problem, right?

Many, many people interact with these employees, and how do I know where to stop? Judith takes a similar point. She says, "How far do chocolate companies have to go to eradicate slavery, and when they do so, do they really address the structural problem or have they simply addressed the consequences of a structural problem? And if they simply address the consequences, do we know the problem is not actually getting worse, as it is in my hypothetical period poverty example?" Those are excellent questions, and thanks to both of you for those. And I think in some sense those really relate to boundary conditions. Let me take Judith's question first, related to the stopping rule. First of all, how do you know when you need to act, and then how do you know where to stop? And if I take the period poverty example, I would start with it being embedded in specific... Start with specific employment relationships, so looking at period poverty among your employee. That's where you have the direct economic relationship with employees, you can

look at your wages, you can look at whether your menstruating employees are missing work because they lack access to products. That's a fairly easy relationship to draw here in terms of where businesses would have a responsibility, but I think Judith is correct to be concerned about this being an open-ended commitment. And in some sense, this gets the first question of whether, in terms of acting, do we leave the structural injustice in place? I think one thing that would need to be worked out in this sort of approach is both of those questions. Where do you stop, because you don't want the business to lead into the role of government and civil society? Businesses, going back to Rita's first question, do have an economic role, and in some sense, I would say that the stopping role really relates to the extent to which you're benefiting from the existence of the structural injustice. If you're operating in a context in which discrimination against women and menstruating people is very high and you're benefiting from that in some way, you have a responsibility to act, and you have a responsibility to act because you have a relationship with your employees. Where you probably would need to stop is when it distracts you so much from the economic mission that you cease being a business, and now you wind behaving more as a government or a member of civil society. And in terms of operationalizing that answer,

that's probably where I need to do some more thinking in that regard. Going back to the first question, when we focused on outcomes, are we leaving the structural injustice in place? In some sense this gets to both individual business action and collective business action. I would argue that businesses can serve as models of behaviour. That particularly businesses that are operating in context in which there are significant structural injustices by their behaviour, they're not just making the people directly affected by the structural injustice better off, they're also acting in ways that develop models of business behaviour that local businesses can adopt and other businesses can adopt, so in some sense, this is where thinking of structural injustice as a collective problem, rather than an individual problem, starts to get at some of the issues of implementation. But I would agree with both questioners that the

implementation question is something that really needs to be worked out more fully. Can I ask one very brief follow up question?you can. I'm also worried here about the fact that it is possible that an organisation with deep pockets is better able to respond to such structural injustices than a small entrepreneurial organisation. These are structural injustices, and arguably we need coalitions of organisations, but might it be that if a large, deep pocketed organisation responded to these injustices, whilst that would benefit its immediate stakeholders, it would squeeze out smaller firms that cannot, for resource reasons, attempts to address them, and that might actually make matters worse? I think that's a good question as well, but that's a question that we've been exploring in business ethics and corporate social responsibility since time began. Well, not literally when time began, when work in the field began. Think about factory monitoring, for example. We've been asking similar

questions about whether CSR imposes costs on firms that large firms are better able to handle relative to small firms, small firms get driven out of business or less competitive, so it's a persistent question, Alan, and I don't think small firms have disappeared. I think it is something perhaps be worried about at the margin, but I actually want to flip the question around, because I think smaller firms may have advantages in another way, in that they truly understand the local context and the way that the structural injustice unfolds in a way that larger business cannot. The large business may have more financial resources, human resources, other sources of resources to respond, but perhaps a smaller business being closer to the structural injustice has a greater degree of understanding, and perhaps can respond better. This also might then suggest a need for partnerships. Again, moving away from a model of individualised blame and responsibility, and toward collective responsibility and collective solutions to the problem of structural injustice. Right. I have more, but we have no time. Rita? Yeah, we do need

to get at least through one more. There's a really interesting question here from Trisha Olson, who's saying you know that you'd like to move away from the actions of individual firms, and yet resolving the collective action problem requires firms to act. Moreover, the pressure points you identify, social campaigns, firm capability, connections, are all at the firm level or at least in a relationship, so aren't we back to where we began in that we're talking about how to increase the cost of wrongdoing from a broader systems perspective? Really interesting question, and in some sense this does then come back to issues related to implementation. If we go to Young's original notion of structural injustice, it's trying to get that past the notion of individualised blame or culpability, or even intent necessarily, to say, "If we all contribute to the creation of structural injustice and its continuation, and we benefit from it in some way, we have some sort of responsibility to act." Young's very clear analysis here is it's a collective action problem. Now, Trisha is

absolutely correct to point out that you still get into the thorny issue of how individual businesses are going to respond. After all, something like a multi-stakeholder initiative is just a partnership of individual firms together. But in some sense, perhaps this question also responds to one of the questions that Alan asked earlier about some firms getting an advantage relative to others. I think a big part of a structural injustice perspective on business ethics is really getting businesses within a particular industry or operating in a particular locale to really look deeply at their business practises. I think this is where there is a need for deeper conversation within, but particularly across firms, to really ask the question, if we're operating in a particular place, are we benefiting from the fact that there are people that we can inflict cost on that have no ability to fight back because they lack power and voice and they're the victims of a structural injustice? So I think Trisha's correct to point out that this does pose an implementation question in thinking... In some sense, it really requires us to think about what are different frameworks that firms can engage in that change the nature of the conversation and the nature of cross-firm cooperation in a way that remedies structural injustice? Thank you all. Oh, and I think we have time for one more, if it's fairly quick.

I think we we're almost entirely out of time. I guess... They're all pretty big, and i'm sitting here looking a bunch of questions that will take 10 minutes to answer and we have a minute.I think maybe we should just make sure that Harry gets a copy of these questions and move on. The one that I like the most I think is a big one.

Thank you everyone for those question, but we're out of time, pretty much. Yes. This is a big topic, and I think it's natural that the questions are all pretty big and complex too. And apologies to everyone whose questions we didn't get to ask, but as Alan said, we'll make sure that Harry receives all of them, so they won't be lost. And thank you again for coming. And Harry,

thank you so much. I can think of a better way to close this term of R:ETRO seminars. It's been absolutely fascinating and thought provoking, and I think we're all going to leave here today thinking quite differently about these questions that you've been addressing with us, so thank you very much. Thank you so much to all of you, and thanks everybody for your participation. And I look forward to getting all these big questions for the next six months of work on this. Yes. Okay, so thank you very much and keep an eye on your inboxes. We will be advertising next term's seminar soon, so I hope to see you all again when we resume our sessions. Thank you and take care. Thank you, thanks again Harry. Thank you.

2022-03-25 13:15