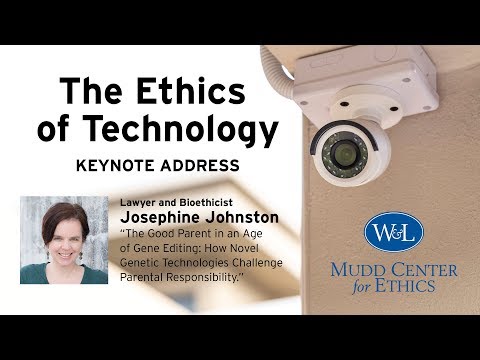

Mudd Center Ethics of Technology Keynote Lecture with Josephine Johnston

Back. In 2010. Class, of 1950. Alumnus. Roger Mudd an extraordinary. And well-known journalist. In America, gave, the university, a generous, gift for, a center, that would look into important. Ethical issues, at the. Time back in 2010, Roger Mudd said, given. The state of ethics in our current, culture this, seems a fitting time to endow a Center, for, the study of ethics and my. University is it's fitting, home, that's. What Roger Mudd said in 2010, it was true then it's it's, definitely. True, now the, center plays. An important, part in the life of the school by, choosing. A topic. Every, year a broad topic of ethical. Importance. This, year's topic is the ethics of Technology, not, a day goes by without. All. Of us reading, in a newspaper or on the internet something. About, the technological revolution, and, about. The. Many. Issues that. That. Revolution. Has, brought about such, things as gene. Editing. Altering. Human, DNA, artificial. Intelligence, and robotics. In, the workplace, and elsewhere. Big. Tech firms like, Facebook, and Google and, the other ones their, practices. Their handling, of private, information. Issues. Relating, to cyber security in which, in a. Number, of noted, situations. People have hacked into. Seemingly. Secure. Institutions. So, we pick that broad. Topic, the ethics of Technology. And, we began then to put. Together a, schedule, of speakers, from, outside, the university and from within some of our own, talent, and we've, come up with a very, exciting. I think schedule for this year's ethics. Theme our keynote, speaker, is a. Bioethicists. Lawyer. And, scholar. And, researcher. Into. The whole area, of gene. Editing, gene, modification. Altering. Of human, DNA, and her, name is Josephine, Johnston. She's the head research, scholar, at an, entity. Called the Hastings, Center in the state of New York she has a new book coming out called human, flourishing in, the, age of gene editing so. She's bringing, a philosophical. Ethical. Perspective. To. Some. Extremely, important, scientific. Developments, we've all read about the. Chinese, scientist. Who, some, months ago said, that he had altered. The DNA, of, to. Microscopic. Embryos. That later. Developed. Into, human. Persons, and are, now born the question, of what. Are the ethical, limits of. Such. Practices, and Josephine. Johnson, is going to lead us through the. Evolution. Of that, question, over time and then, she's gonna pick a specific. Application. Connected. To Gina she's, going to look at the. Good parent. In our culture does the good parent, alter, the genetic makeup, of its children, does the good parent, look into all of this is the good. Do anything to, make use of sect. Technologies. How should we think about, this, what ethical, values, should be part. Of the cultures. Consideration. Of this, topic we're very excited about that as the kickoff. Speaker. For this year's series. You. You. Got. Plenty of seats here you guys. Second. Row here. Right. Good. Afternoon everybody. On behalf, of the roger mudd center for ethics i want to welcome you to the keynote lecture in, this. Year's series on the ethics, of technology. Before. I introduce our, distinguished, speaker. I want. To gratefully, acknowledge, that without the generosity of. Alumnus. And journalist. Roger mudd we, wouldn't be here it, was Roger Mudd who saw. An opportunity. For. A special, place on this campus that would. Focus carefully. On important, issues and their. Ethical, implications. Founding. Director, Angie, Smith. Put. The center in place and developed, a successful, model. So. Mr. Mudd if you were watching on this. Streamed, event. We. Send you our greetings our warm wishes and our, thanks for your gift to the intellectual, life of the school. Now. Each year the Center selects, yeah. Each. Year the center selects a broad theme and invites guests. From. Different, disciplines, and perspectives. To. Address aspects, of the theme this. Year we chose the ethics, of Technology. Given. The incredible, scope of technological. Change in our society and, societies, around the globe, lots. Of change yes. But. Perhaps too little sense of ethical, direction, so. Today we begin a conversation of. What those changes actually, are. Where. They may be leading us, what. Decisions, may be needed, and what, values, will be crucial, to. The conversation. Our, keynote. Speaker, is josephine Johnston, who. Will address one of the leading, developments. Of the day gene-editing. A. New. Zealand, trained attorney, miss. Johnston, has a master's, degree in, bioethics, and health law from. University, of Otago in, New, Zealand, she. Practiced, law in New Zealand and in Germany. She's. An expert on the ethical, legal and policy implications. Of. Biomedical. Technologies. Particularly. As use in reproduction. Psychiatry. Genetics. And neuroscience, in. 2003. She joined, the Hastings, Center as, a research. Scholar now, the Hastings, Center is, an.

Independent. Bioethics. Research. Institute. In garrison. New York. She. Became director of research there, in 2012. She's. The author of numerous scholarly. Articles, her. Commentaries. Also, have appeared, in The Washington Post The, New Republic Time. Magazine, and The Scientist, she's. Co-editor. Of a 2010. Book. Entitled, trust. And integrity in. Biomedical. Research. The. Case of financial conflicts, of interest, this, was published by the Johns Hopkins. University. Press, she's. Also co-editor, of an exciting, new collection. Of essays entitled. Human. Flourishing, in, an. Age of gene editing. Published. About. A month ago by, Oxford, University Press. The. Book is directly, on point with. Our topic, and it. Is hot off the presses. After. The lecture yes, there will be a book signing right, outside that door. Her. Other current, projects, addressed the potential, use of genetic, sequencing. Technology. In newborns. And. The. Ethical implications of. New kinds, of prenatal, genetic tests. She's. Also a member of Columbia, University. Medical Center's. Centre. For excellence in, ethical, legal and social implications. They're. Looking, at psychiatric. Neurologic. And behavioral. Genetics. By. The way MS, Johnson, will be going to the genetics, classes, tomorrow yes, at 8:30 a.m., did. You know that no okay I, could, say more. I just want to stress how privileged, we are to. Welcome, josephine, johnston, to the campus, to share her knowledge and, reflections, on on an, important, topic please join me in welcoming her. Thank. You Bryan and, thank, you everybody as Brian mentioned I'm, from New, Zealand. Altero. And this, is how I speak. You're. Not going to. Get. A different accent, in the course of this talk, so I hope that you can understand everything I say and. Then that spirit I wanted to say tena. Koutou katoa. Which is hello. In, the language of the native persons of New Zealand and I wanted and that spirit to acknowledge, the native, persons of this land and the enslaved people who. Built this beautiful institution, I. I'm. Excited, for you that you've chosen this topic the ethics of Technology for a theme for the year I think it's really fascinating. Of, course I'm a little biased because it's exactly where a lot of my work sets. I, want, to tell you a little bit about where I work because it's an unusual place, and you know I'll say, more about the specific, topic today. Okay. Now make sure that that's. Right sorry, yeah. Okay so first I just wanted to show you where I'm from this, is the. Otago, Peninsula at. The bottom, East, Coast side of New Zealand, and, this is where I live. Now and work now which is the Hudson River Valley north. Of New York City so when I say I'm living in New York a lot of people think Manhattan, but, actually if you travel just an hour north up, the river you get to this very bucolic place, and I live in a small town not that different from this one here, this. Is the view in the winter from the Hastings Center and, this. Is our home, our building the real end we're celebrating, our 50th year so we were founded in 1969. By a philosopher. And a psychiatrist, who, thought, that, there, are a lot of the call and policy, issues being, raised by advances, in science and medicine this is a time when.

Into, Intubation. People breathing, artificial. Ventilation was, just knew. There were lots of questions about, interventions. And psychiatry. And genetics and they wanted a place where people from different disciplines could, come together to discuss, these and try. To make sense of them they, thought they wanted to do this outside of academia because they'd wanted to overcome, disciplinary. Restrictions, in so they created this independent, organization. Our. Research, is focused in two broad areas just in compassionate, healthcare and, the wise use of emerging technologies, we, don't do the science, but we think about and write research and write on the ethical legal and social implications of, it in these, two broad areas so obviously, the wise use of emerging technologies, is very much where I situate, myself and where I'm gonna concentrate today. It's. Just a couple of examples of, projects, that my colleagues work on so where it's a rot wide variety, of topics and. The. Work I'm going to talk about today comes out of a project that we did just recently finished, on gene, editing and human flourishing which was funded by the Templeton, Foundation which, is a private funder private, foundation, their. Work. Led to this book and, I'm, gonna draw very heavily both on the book is and, on my own essay and chapter. In this book. So. As. Many, of you know since. Well. At least since the double helix structure. Of DNA was discovered over, 50 years ago we. Have been contemplating the possibility of, making site specific, changes, in the genomes of selves and organisms, it, is, long been clear that human, and humans, traits, are definitely, influenced, by genes. Sometimes. Heavily, even if it has been difficult to understand, exactly which, genes and how. We. Eventually gained, the ability, to map the human genome and we've learned a lot about how. Genetic, differences, influence, disease risk. Disability. And other, traits. And characteristics with, a high I color. Other things like that our. Ability, to act on this information however. Has, been pretty limited, until now we. Couldn't. Make this we couldn't we could ID specific. Genes and shows, identify. Specific, places in the genome that had an effect we, could say what they did but we could not silence, or alter them. All. That changed, in 2012. When. These. Two, scientists, and their collaborators, publish separate bio way papers. About. A new, gene editing tool, called. CRISPR, kes 9 I'll. Say a little bit in a second about how the Tool. Works it's. Adapted. From the Beck the immune. System of bacteria, so it sort of came in to genetics. And a somewhat. Obscure way in a field that really hadn't had much attention and this. Woman especially Jennifer, Doudna had worked in this area for a long time sort of an almost obscurity, and then, suddenly became one of the most famous scientists. Alive. Crispus. Stands for clustered, regularly interspaced. Palindromic. Repeats and. Ks9, refers, to. Enzyme. On, the molecule so this is a diagram I did not draw this diagram and. Also I'm not a scientist. So I'm not excellent, at describing it but for, our purposes, here's, what I think you need to know, the. Blue blob, is. Cast. Nine it. Guides. Inside. Of it as a piece of guide RNA, the purple, loop, that. Piece of guide RNA, guides the molecule, to a specific, place on the genome, the. In the case nine, X's. Appear like molecular scissors as the phrase often used to cut two separate. It's got a little arms around that separate, and cut. The, genome. Then. The, gene, is either repaired, and often silenced, or new DNA, can be introduced, so in this diagram there's a green piece of donor DNA that when that cell repairs, the break is inserted, into the genome. This. It, turns out that this system, is, able. To make changes, in the DNA of. Cells, as well. As organisms. From. Everything. From bacterial. Cells to zebrafish to, mosquitoes, to, human cells so it's a remarkably, versatile, system, it's, not the first thing we've ever had that. Allows us to make changes to DNA but it is far, in a way the most effective and, easy to use of any of the tools. From. Our purposes. It's important, to know that this can at least theoretically be. Used in any kind of human cell whether. Those cells are sperm, and eggs embryos, and, fetuses, in utero babies, children or adults.

This. Is the area I'm most interested in the post the use in humans. When. CRISPR, case 9 was, came. Out and when when it became clear in, the couple of years following its discovery the. Implications. Of how versatile, it was and how what it could be used to do it was, really, heavily covered in the media so, I am sure that most. Of you have heard of CRISPR even if you don't know what it exactly is. It, was on the cover of all sorts, of magazines, and as, you. Can see the headlines, were fairly dramatic. No. Hunger no pollution no disease, which sounds good and the end of life as we know it so that was one unwired. Its. Implications. For use in humans and particularly, and reproductive, contents, was lost on nobody, and these. Are two headlines, covers. From magazines, from 2015. And 16, showing. That people are already thinking how, might we use this in humans. Here. Is a paper that really starts to get at the direction I want to take my remarks in today which. Is this question about whether or now that we can potentially make changes, in future generations, we might have some kind of obligation to. Do so I. Want. To say a little bit about why, I focus. Here I want to focus on parenting. I think. It's an inherently, important, area. And. I also think it's overlooked, so. This. Is not the first technology. That will have implications, for families. But. It is one of the first that could allow directed it's the first that could allow directed, changes, to be made to, sperm. Eggs embryos or. Children. And. The areas of research in which I works are in high field my. Colleagues, and I spend. A lot of time thinking about what. It might mean for those, future, children who have been created. With the aid of CRISPR. But. I want to shift today and not focus, so much on the, eventual, children, and whom this might be used but the parents or prospective, parents, who, would. Sort will soon be asked to consider consenting. To this use of this technology and their children, these. Parents, and prospective parents, are not usually, understood, to be the direct subjects, of a technology, right this it's they are not the persons, whose, genes would be changed. But. They, will be asked to make decisions. For others in the context of one of the most significant, in intimate, relationships, that humans experience. The. American parents, who will be the first to be offered gene editing of their gametes, embryos, fetuses, or children may be in this room today. They. Or you will, be called upon to make decisions, that I did not have to make when I was a prospective, parent and that I have not had to make since, my child was born as a, result their. Experience, of parenting may be different, while. Not the ones on him whom the genetic technology, will be used there, nonetheless impacted. And they, preps, could even be changed by it it is. This ability of for gene editing to impact parents, in prospective parents, that I will focus on today in particular, I'm, interested in how new. Kinds of genetic technologies. Like this interact, with ideas, about what good parenting, requires I. Will. Focus today on the new gene editing tools of course because. They're the most dramatic, cutting-edge. Genetic, technology. But. Versions, of my analysis, can be applied to parental choices, about whether to use a wide variety of genomic, technologies, including. Many that are available today and that the young people in this room will certainly be offered from. Carrier, screening to genetic testing of, embryos, to prenatal genetic testing to the sequencing, of newborns, in children. The. Other reason I want to look at parenting, in this role in the gene editing debate is that I think it's a good proxy for some, of the ethical or, moral issues, raised. By uses, of the same technology, outside the, reproductive, context, when. People say that using something like CRISPR, in adults or in, non-human, animals and insects, or implants, is playing. God or against. Nature, there's. Sometimes making, an explicitly, religious, argument, but. Often, they're expressing. A discomfort, with, the degree of control, that such a technology gives us over the lives of others and they, just don't have other words, to express it it's. Not that humans are always uncomfortable, controlling. Other creatures, in the natural environment we do that all the time but. We've also come to understand, that it can come with downsides, and can leave us feeling that we have become responsible, for a fix, whose magnitude, we never could have imagined, I'm interested.

In Their kind of concern, about, control. And I find the parenting, context a fruitful place for exploring, that larger question. Because. I'm going to be a bit negative in, this talk I, need. To begin my argument by noting, that genomic, technologies, including, gene editing can. Bring real benefits, to future children they. Could offer parents, and clinicians, new ways to improve, children's health, and well-being the. Cause of some mysterious diseases. Or disorders might finally be understood, some. Conditions, might be cured or better treated parents. May be better able to anticipate and, address their. Children's educational, and behavioral challenges. Although. Many scientists, researchers, and commentators, remain cautious, about the possible use of gene editing technology, and gametes. Embryos and fetuses early. Research in this area emphasizes. The benefit, of eliminating, serious, disease from families and perhaps, from the human gene pool altogether. To. Probe this possible, use some research groups have been you gene-editing, technology. Is crisper in human, embryos in the lab to. Repair genes associated, with, beta thalassemia a heart disorder called hypertrophic, cardiomyopathy in. Marfan. Syndrome which, are all lifelong, and in some cases lethal, conditions. While. None of the, embryos, in those, experiments, were ever transferred, to a woman's body for gestation, and birth a, scientist. Named hee Jun cui and China recently did just that. You. May have heard it you, may have heard of him, he. Used CRISPR gene editing, technologies. To make changes, to the genes of single, cell embryos, right after, fertilization with. The aim of making them resistant, to HIV infection. This. Top, photo is a screenshot. From. He. When he would you and he dr., he in. A series of videos, that he made in, order to announce his discovery, to the world you can find them on YouTube he. Was actually scooped. By a newspaper, or a journal. MIT Technology, Review two.

Days Before he was due to make the announcement. We've. Known for a long time, that people work for a while that people with a particular genetic, mutation. Are highly. Resistant, to HIV infection it's. On the ccr5, gene and, this, Chinese experiment. Don't that he sought to give human embryos that same genetic difference, so, that the resultant, babies would be unlikely to ever contract, the virus. Here. He is talking. About his work at an international summit, that happened two days after, the story broke about his experiment. He. Called his study a kind of genetic surgery, or genetic, vaccine, much. To his surprise when. The study was announced, in November, last year, the. Work was actually roundly, condemned, as being both premature, and irresponsible. Now. There's a lot that we could say about, this work, and I'll be really happy to talk about it in the Q&A for, now though I just want to note that this experiment, for, all its problems, was. Proof of principle, that editing of human embryos can be done and babies, can be born as a result, whether. The Chinese experiment. Or any other possible, use of Jeannie, be shown to be safe and effective remains, to be seen however if. Safety. Can be addressed in some scientists, are confident, that it can gene. Editing technologies, could one day be applied so that the future child is never at risk for genetic diseases so. That their risk is greatly reduced or so that they would be expected to be slightly taller. Of slightly, higher intelligence. More. Athletic, than they would have been had their genes not being edited, if, genetic. Technologies, in general and gene editing technologies, in particular can, really offer those benefits, it. Will be very tempting I think to welcome, them as new ways to promote, the welfare and social advantage, of children as providing. Exciting, options, for reducing suffering, and advancing, flourishing, as wonderful. New choices for parents and prospective parents committed to the welfare and future, of their - of their children and future children after. All what could be more constituent. Of good parenting than. Promoting, your child's health and chances, of success, even. If that child does not yet exist I. Want. To back up here for a second and explain why I think that at least some prospective parents, perhaps, people in this room today are likely to have this choice to use gene editing and their. Future children despite. The experiment, that occurred in China these, genetics, editing technologies, are actually not available to prospective parents, here or anywhere else in the world in fact, because. Altering, the genes of an egg sperm or embryo would result in a genetic change that, is heritable, that. Is that a genetic change that is able to be passed down generation. After generation, this. Kind, of use of gene editing technologies, is currently against the law in dozens, of countries including. The UK Canada. Brazil, Australia many, European, nations and it's against national guidelines and many others here. In the US, lawmakers. Have adopted a rather unusual, but not unprecedented way, of dealing with this possibility, rather. Than having a law directly, prohibiting. Heritable, gene editing which. Is what a lot of countries have done the US has since, 2015. Passed. Something, called a budget writer this. Is a, small, section. Inside, a gigantic. Budget. Bill and in. This case it includes the following provision.

If. You can see that from there, when. I this, is an at 101, word budget, writer and, in its current iteration. It's in a I, think, a hundred and fifty thousand, word bill piece. Of legislation, so, it's, not super easy to find, what. This law does is it prohibits, the FDA, from considering, any application. To do a clinical study in which a human embryo has, been intentionally created. Or modified to. Include a heritable, genetic modification. And the. Reason that works, as a ban, on jamp germline gene, editing is that the FDA has. Asserted authority. Over any experiment. In the United States in which, genetically, altered cells are used in a human being, meaning. That anyone who wants to do that kind of work has to go to the FDA for approval and, as, a result of this budget writer the. FDA, is prevented, from concert', even considering, even responding, to that, kind of application if, it would involve making a heritable change to, a human embryo today. No US researcher, can transfer, for gestation, an embryo made. Using, a gene edited gamete or an embryo that itself has been altered using gene editing technology, so that's the law as it stands and this, budget writer has now been passed four times. My. Prediction, however is that if techniques, show significant. Promise, determined. And well resourced, parents, will work around these controls, just as, they already do in order to access certain kinds of assistive reproductive, services that. Are not available in their countries they often, come to the u.s. because the u.s. allows a lot of reproductive, services that, other countries, don't and, if. Gene editing specifically. Is shown to be safe and effective even, if only for one or two serious, diseases, then this kind of blanket prohibition in, restriction. Will, not stand. Jurisdictions. Including the US, will. Face compelling, requests from scientists and clinicians and families to revisit, these laws so that families, carrying genes for serious diseases can. Use the technology. Even. Or maybe actually precisely, because the. Changes, they make will, be passed on to future generations. Then. The decision about whether and in what ways to alter the genes of future children will. Very likely risk, not with members of Congress but. With parents, and prospective parents. Which. Raises the question how. Will they decide what to do of. Course no two decisions, will be the same in its likely, that many and varied considerations. And influences, will, shape the decisions, of individual, parents, I know that everybody is different, yet. If patterns of decision-making about the use of other genetic, technologies, and similar contexts are any indication, among. Those considerations, will, be ideas. About what a good parent would do I, say. This because research, on parental decision-making with existing genetic technologies. Like prenatal, testing and genome sequencing, already. Show us that the idea, of the good parent, is at play in decisions, about genomics, and there, as parents, currently understand, this idea being, a good parent requires, them to maximize their, use of the technology for the good of their children, or future, children in, one.

Such Study. I've. Shown up here for people who need the citation. Researchers. At the Hospital, for Sick Children, in Toronto offered. Parents, full, genome, sequencing, of their children, the, children had. Specific, health problems and they've been referred for genetic testing to the clinic and at. That time they were offered, the option of instead of having ordinary genetic, testing to have the whole genome sequenced, if the, parents agreed to this they. Would receive not, only results about the child's condition about, whatever it is that sent them to the clinic in the first place but, also results, associated with other kinds of childhood, disorders, and. If. The parents wanted, the, parents, could elect to also find out whether their child carried genes associated with, conditions that, would only occur, decades, from now in adulthood. This. Would include things like the Brecker. One and two genes which. Are associated, with high, risk for ovarian and, breast cancer. In adulthood. Where. The study got interesting. Is that even if parents, didn't want to know that kind of information about. Themselves because their art they were also sequenced, in the study most. Chose, to learn it about, their children. Researchers. Who interviewed their, parents about their decisions reported, that many parents, expressed, ambivalence, about learning. This kind of information about their child's, risk for diseases, that may not come, for 50 years because. They realized that while this information might be theoretically. Able to help them prepare their, child for them dealing with this condition later, in life when the parents may be gone it might. Be difficult for the parents to make sense of these genetic findings, and they, realize that it could cause them significant, worry industries. So. The parents, knew that finding out this kind of thing about their children could have downsides, for them yet. They almost all, agreed, to receive these additional results because they felt they ought to no. Matter how unpleasant as the. Research has put it faced with this opportunity this, opportunity, to receive to child risk for adult, genetic, conditions, parents. Felt they had no choice. This. Version of the good parent where parents ought to know all they can about their child or future child's genome is in, the interests of the genetic testing companies, of. Course and indeed, it is already their message. This. Is Anne Wojcicki the CEO, of 23andme. In. 2016. She told the new the Observer newspaper and the UK I tested. My son is as he, was born as soon as he was born and I tested my daughters em the otic fluid, genetic. Testing is a responsibility. If you're having children a. Construction. Of good parenting as requiring, maximal. Use of genomic technology, is also consistent, with the rhetoric of some very prominent scientists. Whose the universal, use of genome, sequencing at, least as a, welcomed, fait accompli. You. May know Francis, Collins he's an American geneticist, who led the human genome project and who's, currently director, of the National Institutes of Health and in, 2010. He wrote this he, has repeated, it in, slightly, different format, more recently he, said I'm. Almost certain that whole genome sequencing, will become part of newborn, screening in the next few years it's, likely that within a few decades people, will look back on the current circumstances. With a sense of disbelief that we screened for so few conditions. He. Surely doesn't, plan to force, sequencing. On parents, but, the benefits, of it are so clear to him that he assumes that sequencing, is something that all good parents would, want.

Now. We may or may not agree, with Collins's. Prediction, but, what I want us to notice here is that, this idea, that, good parents, choose to use genetic technologies, to the maximum, extent. That. If that, that idea plus the technology that really could offer a child a miracle benefit, if it, works well so there's a lot of us there. Idea. Could. Rather quickly. Reach the point where utilizing. This technology is, not simply a choice or an opportunity for. Parents and prospective parents not, merely something that good parents can do to benefit their children but, a new responsibility, of parenting, something, their parents ought, to do, I'm. Not suggesting that it will be required by law at least not initially but. It might be required by at least some prospective parents, culture or social group it could become a norm of parenting, these. Parents and prospective parents might feel is the Toronto parents dead that they have no real choice about whether to agree to using, genomic technologies, because. Using them will be synonymous with good parenting I. Want. To point out an important, problem with thinking about these technologies, in this way, while. Gene editing may well benefit, future children and needs to succeed that notion for now it. Might not be an out-and-out, boom for parents and prospective parents, and I'm going to spend a little time now thinking, through some of the burdens that a technology, like this might place on parents. At. Least. In its earliest, iterations. It's likely, to be physically, burdensome, to, women in particular. Right. Now if you require it would require prospective. Parents to refrain, from procreating. The old-fashioned, way and to. Instead, in vitro fertilization, which involves medical testing, medically-induced. Super. Ovulation in, surgical, egg extraction before embryos, can be created, in a lab tested. Edited. And then transferred, to the woman's uterus for gestation, if. Frequency is not achieved or does not lead to a healthy birth the process, may need to be repeated. Significant. Physical discomfort, in some health risks accompany, IV if we know this already, yet. The need for this process, is really discussed, in coverage of germline gene editing in China, that all of those. Embryos. Were created, using IVF, and all. Of the cup that eight couples that were in this experiment, all had to undergo the women all had to undergo IVF treatment, as part of the study but you never hear about their. Use. Of gene editing might, also come with a time burden, oh. Sorry. IVF. Takes many months if you, just compare this to how we many. People procreate, today, IVF. Takes months from, initiation. Of testing through egg development and retrieval, embryo creation, and testing and embryo transfer, in addition. It. Can remain uncertain, sorry. In addition. That. Genomics. Behind. It will. Remain uncertain and complex for a long time to come is one. Genome scientists, recently remarked, it's misleading, to equate advances, in big data in genomic tools with similar, strides in understanding how, genetic, differences, impact, health so. Clinicians, who are dealing with patients going through IVF before doing gene editing will need to take a lot of time to, discuss sequencing, results in gene editing options, and the implications, of various choices, with respect of parents. Understanding. This complexity, in making gene editing choices will likely be cognitively. Burdensome, for clinicians, in prospective parents, alike to. Study your genome, geneticists. Compare it to what are called reference genomes or databases in. 2015. Which in the context of genomics is a long time ago. Without, the thousand genomes projects. Reported, that a typical genome, differs differs, from the Prinze human genome at 4.1. Million to 5 million sites, and contains. An estimated. 2,100, to 2,500. Structural, variants, affecting, about 20 million bases, of sequence this. Is just a really highly, technical, way of saying that. While some disorders, and diseases have. Clear genetic causes many. Are far more complex than that and much, is still unknown. Utilizing. That results, of genome sequencing deciding. What to edit and what not to edit which risk to take and which to seek to avoid could also be emotionally.

Burdensome, We. Already know from. Multiple, studies of decision making around prenatal, testing that the presence of genetic, markers especially, those that would have an uncertain, impact on the future child can, generate significant, worry and prospective parents, now. If gene editing could repair those genes it, might alleviate the worry you would think but. The same research in the prenatal context, indicates that, wory can continue, even after the all-clear is given we. Just continue, to think that something, might be wrong even. If a healthy child is born and we. Continue, to watch. That child, more closely than, if we had never had these genetic interventions, in the first place, we. Also know from research on prenatal testing, that prospective parents. Can be distressed, by the information, they learn about themselves and their partners in the process of testing their pregnancies. Sometimes. They find out that they carry variants, associated, with autism or cancer, or schizophrenia. Or early onset Alzheimer's things. That many adults actually choose not to find out about themselves, gene. Editing would require, sequencing. That's how it would begin and it. Would turn up these same kinds of potentially, unwanted, or unexpected. Information. It. Would also be financially. Burdensome. Yet. Be something that, parents feel they ought to pay for, costs. Would exceed the twelve to fifteen thousand. Dollars associated with a single cycle of IVF because. You would have to do the IVF and then the editing on top of that and like, IVF, we would we should expect significant, variation, even within the US about when, access, to technology, will be covered by insurance and when it will fall to individuals, to pay. Well. Paying for gene-editing the unexpected part of the cost of childbearing, much. Like the cost of child care in college education, will, people go into debt to pay for it as they already do to cover IVF, and other reproductive technologies. Finally. And I think this is where, things get pretty interesting, some. Or all uses, of gene editing technology, in the reproductive, context or work will require parents, to consider, acting. Against, their values or deeply held beliefs in a. Study by UK, researcher, Jackie leach Scully that's actually discussed. In our book some. Parents, have argued that it is wrong for a parent, to seek significant. Control over their future child precisely.

Because, Too. Much control, risks, compromising. A fundamental, feature of parenthood one. Their parents benefit, from as much as the future child. What. She's saying I think is that. Users. Like this and reproductive genetics. Can, cause parents, to have to act in ways that are. Deeply. Distressing, to them, and. In. This concern, about reproductive, genetics. I see a parent, focused, argument, that dovetails, with, the one I'm trying to make today there points, out that parents and prospective parents might themselves be, harmed. Or compromised, by the kinds of choices they have to make about their future children if they're using gene editing, one. Such values conflicts could Center on the nature of disability. A prospective. Parent who sees some if not all disabilities, is thoroughly consistent. With living a good life could. View the choice to edit a gene associated, with a particular disability. As the. Displays, the adoption, of a discriminatory or misguided view, to. This parent, choosing, for example, to eliminate, a gene and their embryos for deafness or autism. Might. On the one hand benefit, the future child but, on the other directly, conflict, with their parents, understanding. Of those conditions, as differences, to, be embraced not. Disorders, or faults, to be repaired. And parents. Finding themselves in their kind of moral. Dilemma could. Fight could feel deeply, distressed. Reproductive. Use of gene editing could also conflict, with a prospective parents, understanding. Of the nature of parenting, for. Such a parent, and I actually, count, myself amongst, this group the. Parenting, role importantly. Involves. Having to balance, acceptance. With. Control. These. Kinds of parents might be reluctant to, use gene, editing technologies. To its fullest extent because, being a parent who knows that, much about in exercises, that much control over the appearance genes could. Conflict, with the kind of person they want to be in the kind of parenting experience they are committed to having they. Just might not see themselves as always, needing to be the maker or the fixer, of their children, although, this, is the exact role that the technology, seems, to put them in. These. Burdens, on parents, which are seldom acknowledged, will not be experienced, by all parents there are people who don't, care about any of this and for whom none of this is a problem and they. Won't weight equally, on all who encounter, them but. They will be very real for some people they, could fall disproportionately on, women, especially the physical, burden associated with. IVF. And that embryo, testing, and editing, and. They. Would also be especially difficult for the poor they're. Disabled. Those were the history of genetic disease and their families and those with particular religious. Moral, or political commitments. The.

Reality, Of these burdens, means that while using gene editing and other kinds of genetic technologies. Might arguably, benefit, children in future children doing. So could also negatively. Impact, the health and well-being of parents. Does. That matter. Does. The potential clash between the, best interests, of future, children and the flourishing, of prospective, parents, Mehta, in. Particular. Does it matter for our understanding of good parenting if, we. Think that a good parents, sole obligation. Is to further the best interests, of the children, then no it. Doesn't matter, but. If we think as I want to persuade you their parents. Flourishing. Matters, to that. Good parents, also need to take their own interests, as persons. Into account in their decisions, then. Yes the burdens on parents are relevant to our understanding, of good parenting in an age of gene-editing. The. Problem, is police, in the circles I move in that, this idea, that parents interests. Are part of the equation is not, widely, accepted, or even discussed. I'm. Certainly, not the first person to ask whether prospective, parents, should seek to control the genetic makeup of their future children but. I am one of the first to suggest that parents own interests, belong in the equation. Of that dilemma. Arguments. For and against parents, and prospective parents, seeking this kind of genetic control they've actually been made by a huge variety of scholars and philosophy, religious, studies bioethics, and other disciplines, and fields and amongst. Those scholars, there's not agreement about whether or not or, how much parents. Should use genetic, technologies, but. There's near total agreement that the best interests, of the child alone, are constituent. 'iv of the obligations, of parents, and prospective parents good. Parents, act in the best interests. Of their child or their prospective child and the disagreement is about. Whether. Using, genetic, technologies, as the best way to do this so here are a few examples I. Think. This. Is Robert Greene, he's. At Dartmouth and he's, argued. That parents, should strive, to give our, children lives, unimpaired, by serious, genetic or congenital disorders, and we should take reasonable care to avoid doing so by, inadvertence on, a glit so. Here he's coming out in favor of using genetic, technologies, to try to benefit. Children. While. He doesn't believe, that this obligation, stretches, beyond serious, genetic disease, the, philosopher, Julian Savalas COO shown. Here. Goes. Through that arguing, that for, a principle, that he calls procreative. Beneficence. Which, he says requires, parents, to select, the child of the possible children they could have who is expected, to have the best life so. You make a lot of embryos, we have them tested and you select the ones that, are expected to have the best possible life an obligation. That he now extends, to the use of gene editing technologies. Baked. Into these arguments of several iscoe and Greene is, the idea, that parents use of genetic technology should be guided by whether their use could significantly reduce. The, future, child suffering, or promote the future child's flourishing, the, flourishing, of parents is not discussed. Similarly. And perhaps more surprisingly, scholars, who've raised concerns, about parents, use of genetic technology, are also focused. On the well-being of children, the. German philosopher Jurgen. Habermas who's. A real critic I think of genetic, technology, fears. That a child's, freedom could be damaged by the use of genetic, technologies, as could. The nature of that child's relationship, to their parent and the. U.s. political, scientist, Michael, Sandel and ethicist Adrian Ashe both, urged parents to reject genetic. Technologies. Here. They are. This Adrian. Who. Says said that the norms of good parenting include fostering, and supporting, the uniqueness of individual, children with all their mix of talents, personalities. Strengths. And problems, here's. Send out saying, a similar thing to appreciate children, as gifts is to accept them as they come not as objects of our design or products, of our world or instruments, of our ambitions, so these are two people who. Are skeptical, very deeply, skeptical if not opposed to the kind of selection and control, that genetic technologies, promise parents.

On. They're. Different but consonant, views good. Parenting, real parenting, is about acceptance, and openness virtues. That ensure, the well-being of the individual, child who will be born again. It's a focus on the child's best interests, now, I don't dispute, the importance, of the best interests of children and our understandings. Of good parenting I think. It's probably an accurate focus, it reflects how parents, actually make many key decisions, and it, will often be an appropriate, rule of thumb it's reasonable. To, imagine their parents are acting and the Beast enters their children but. Notice in all of this parental well-being, is completely, missing from these understandings. Of what it means to be a good parent, indeed. On these constructions, it might be selfish, and therefore, completely inconsistent. With good parenting to even consider let. Alone on occasion privilege the, well-being, or flourishing, of parents, this. Characterization. Of the obligations, of parents, is just, not realistic, or fair. While. I recognize, that the flourishing, of parents in the flourishing, of children, are frequently. Inseparable. Asking. Parents to attend only to their child or children's, interests, to the exclusion. Of their own, establishes. A limitless, responsibility. That the vast majority of people will fail to discharge. Further. It is simply, not fair to define the role of parent in such a way that individuals, taking up that role must give up attending to their own interests and values or, must always prioritize, the interests of their child if there's a conflict between the two asking. Parents to adopt such a demanding, understanding, of good parenting is akin. To saying to them when. You become, a parent you must cease to understand, yourself as a person, with interests, and a life story. What. Might a more, accommodating. Reasonable. Understanding, of, good parenting mean, for, our use of genetic, technologies, like. Gene editing. One. Result, would be, that. We that both the choice to use in the choice not to use gene editing technologies, could. Be consistent. With being a good parent depending. Not only on what the technology could do for the future child but, on the burdens or demands it might place on the parents, this. Understanding. My legitimize, a parent's decision not. Only to find out and seek to control some aspects of their child's genome but, also to place, certain, limits around how far they are willing to go to. Allow them to leave some, things to chance. Practically. This, approach means that prospective parents. And parents. Need real choice about. Whether and how to use genetic technologies. Which, means that Rutten is a of genetic technologies, in ways that obviate, choice as well, as social pressure to use the technologies, we'll both need to be avoided. Because. The idea that parenting, is only about the child's best interests, or their child's flourishing, is deeply, ingrained, in Western culture, along, with the idea that considering, parental, interests, or well-being is selfish in an appropriate, an attempt. To broaden the concept of the good parent in the way that I'm advocating will. Require some work some. Of that work can be undertaken by social institutions, including, schools colleges and universities, the. Media and the arts can, and already do play, a significant. Role in testing. Our assumptions, about the relationship, between technology, and human. Flourishing and this is an issue that they also address. Individual. Prospective. Parents, may also need help to. Reflect on their own values, and interests including. What they care about and why and to consider what a decision to edit or not to edit might, mean for who they are as responsible actors, with their own life stories. Clinicians. Clergy. Teachers, counselors, family. And friends can, encourage, this kind of nuanced, self-examination. Finally. We need of course supportive, loyals policies, and practices, that make, it possible for people to really choose how, to use the technologies, if, you. Live in a culture, that. Punishes. People for having brown skin or. Some kind of disability then. Your choice about whether to use genetic technologies, will be deeply, shaped by. The lack, of supportive laws policies and practices, and your culture. This, is the bit where I put up a picture of myself I. Hope. I have persuaded you, or at least opened, up the possibility, in your, minds that good prospective, parents, have, responsibilities. To future children, but, also to themselves, and. That, the burdens a technology, that like gene-editing could place on them including.

Pressures To Eskew their own values, and act in ways that are inconsistent with their flourishing that. Those pressures, are relevant. Durations, in both individual, decisions, about whether and how to use the technology as well, as policies, and norms shaping those choices, it's. Incumbent, on us I think to recognize the, burdens on parents, associated. With this kind of intervention, and to, be open to supporting parents who act to protect their own flourishing. Only. With this richer, understanding of. The nature and responsibilities. Of parenting, can, we adopt technologies. Like gene editing in ways, that benefit, parents, children, and generations, to come, and. With. That I would like to open the floor to your questions. This. Is me with my child. Who, definitely, has taught me some of these lessons the hard way. There's. A microbe there are two microphones so it's helpful, to use them it thanks. So much um so. As I understand it you're really thinking about the. The, responsibilities. Of the parent to children, and to themselves I'm curious what you would say or what others in the field would say about the responsibilities, of a good parent to the community, that, is what what is parental responsibility, when. It, involves. Participating, in us in something, that will certainly, perpetuate. And expand, inequality, mm-hmm, so. Um. In. Me. Some. Of the people I I previewed. You. Know very, briefly. Care. A lot about. That. Question I think in the way that you mean it so by, saying that what I mean is they care a lot about. Adopting. Technologies. That perpetuate, inequality, or make an equality worse and that, could happen if a beneficial, technology, so if gene-editing turns out to be helpful for providing, social advantage. That. They, would be concerned if that were only available to wealthy people okay. But. There's another version of your question. Which. Is, that, there are also people who argue that it is an obligation, of you of parents, to think about the burdens, that their child might place on society, if they, don't either, genetic. Do, prenatal, testing or embryo selection or, you, know one day gene editing so. So. Julie and savelist go in particular. Frames. His procreate of beneficence, is an, obligation, that a parent, has or. A future parent has to. Well. That's the thing he's never really entirely clear about who the obligation, is owed to the. Way it's framed implies, that it's owed to the future child. But. You can't help but feel in his discussion, that he's also concerned. About. Improving. The overall sort. Of genetic. Fitness. Of. Society. Or, a country, and. There. That. He. Feels that we have an obligation to, each other to sort of have the best possible, child by, some, set of, sort. Of optimization. Standards. That he has in mind so it's, both in their really different ways of thinking about what justice, requires, of us with. Really I think almost. Incompatible. Outcomes. Hello. Can, you expand, a little bit on the idea of editing. And adult streets and how that would affect parents, who are much older since this individuals, already an adult yeah so. Right. Now in, disco for, the longest time including, now in discussion. Of this kind of making changes in people's, genes because there were other tools to do it they just didn't really work that well before. The. Discussion has distinguished, between what. Are. Called somatic changes so. Changes. In cells that are not. Passed. On to future generations so basically if you make a change in the genome of an adult like taking, it like you take some bladder they're body change their, genes and that blood and then put it back in. We. Don't think that it will end up in your. Eggs or sperm and it won't be passed on to any children you might go on to have so if you had a problematic gene and your that was causing you to have a disease and you got treated with a gene editing to therapy. That. Would not prevent you from passing, that gene on to your children and so. There's this distinction, between what are called somatic changes and, what are called germline changes. There. Is a little gray area in there because, there are some interventions. That you could do in utero for instance that could. Look, like somatic. Changes but they could end up at least partially, in the germline so and. It. Hasn't we haven't done it enough to be totally, sure but the theory is that these are separable, so. There. Actually are already. Clinical. Trials of CRISPR. And other. Gene.

Editing Technologies, and adults with genetic, diseases just. A few and, on. Cancer, to, end those. Are assumed. To be somatic. Editing, studies. Where there would be no way. That that, changes. Could be passed on does. That make sense. Thank. You and thanks. So much for your talk I. Was, I was. Wondering and. I'm really, sympathetic, to what you have to say but I became. A little bit puzzled, about, whether, and. Parental. Interests. Were completely, separable. From. The child's. Interest so you're you know worries about parental, interests. And makes. Sense and the separation, between the parent parents interests and the child's interests makes sense if you're talking about specific, individuals so, like of course, you know I. Can benefit, from, something individually, that my son doesn't benefit from and vice versa but. When it comes to broad, changes in the culture or broad, policies. I'm wondering. If we can maintain that separable. 'ti of interest because of course the, typical child grows, up to be the typical parent and so. If worried, about right. So if we're worried about you, know, burdening. Parents. Like a policy. Or a cultural change that burdens, parents or changes. Things for parents that stresses, them out or makes life worse, well. We would also, be talking. About burdening. The children in that way given. That they'll probably grow up to have children unless. You. Think that you can make some of these changes in a single generation. So. If your. Idea is like well we could do genetic, changes, on one generation, so. That they then would have these extra, good genomes that would be passed on then they wouldn't need to do gene, editing for, their future children, I. Mean okay but the. So. That's, really just a, almost, weirdly. Technical. Answer to your freedom I think. That the philosophical, point, that I I'm not sure if you were gonna say we're, saying but that I think about is that I've constructed this argument as if there is the separation between their interests of parents and children and I understand. And actually agree that like that, separation. There's pretty artificial most, of the time. It's. Just that. It's. Very easy for, that. Fact. That we never notice. The. Ways in which these, technologies, impact, women and in, particular, and.

Parents In general so. If. You assume that the. Parents. Have and their children's interests are intimately connected and you then talk primarily about children's. Interests, it's. Very easy to forget that, all. The people in here junk we study the, women all had to do IVF no one talks about it or. That. Be. Offering somebody, a gene editing technology, to get. Rid of deafness, and their family, could. Actually cause, the parent, to have to decide. Something that they find to be deeply offensive so. And, one of the reasons that I've because, I'm sort of. This. Procreative, beneficent idea. Could. Make. You you could. Be an argument for for, instance only having boys. Because. Most, cultures, it's better to be male maybe not I don't know but in some cultures it is right so just. Post straight up so. There you could say well that means that everybody then if you lived in that culture and you really wanted to give you a child at the best possible life you would make sure they were event male, or. You know if you have brown skin you can make sure that they don't and, that. Would, involve you having, to do something that could feel like the exact opposite of everything you stand for, so. That's the tension that I'm interested in and some. And to discuss it I almost have to artificially separate the interests of children and parents I see. But. It's not that I think they are a completely separate because I was thinking of that as like a way as like a like, a way to kind of another, way to convince, people who were only talking about children that they should. Know. That, the children themselves will become parents when are they to it yeah yeah, I mean I don't. Know what other, people here think but my. Feeling. Of. My. Feeling about the American. Standard for being a good parent but there's, sort of being an adequate parent but then this thing like a really excellent parent, is that it's it, tremely expensive, so, it's coming from another country to the United States and. Then having a child here I was sort of shocked at like what I got, heard, were the sorts, of financial. Resources that I'm supposed, to accumulate. For her. For. College and also apparently her wedding which. Where I come from you pay for yourself, and. I. Just couldn't imagine how I could possibly save one hundred and fifty thousand dollars like, in the course of her lifetime and. And. Yet, that seems to be feeling widely accepted even though the majority of Americans can't do it. So, I was also a little bit spurred, to start thinking about this tension because, I just felt like when, you go to another culture you really notice the things that have sort of baked into their cultures assumptions, it's not like there aren't those assumptions in New Zealand about different things I just didn't know what you know then I was obvious to me.

So. Those also were kind of on my mind oh. And. Then there's someone at the back after the jinhwan, and the purple. So. One, of the things that you talked about was, of course expense, and another thing that you talked about was the uncertainty. Of if, we make a change here what, other effects could this potentially have so, if we were finding the technology, say a hundred or a thousand, years down the line to, where we can be a hundred percent certain, that an edit here will have no secondary. Impacts. On the child which could potentially be negative and we can also share ensure, that it's so affordable that any, parent, regardless, of socioeconomic status. Can afford to make these changes would. You then say that a parent would have an obligation to, prevent. Something such as say, autism. In their child so. Um I. Let's. Say so a lot of the burdens on my list could you know as you're saying potentially, be alleviated, including, the OVF one actually because there's this idea that we could make sperm, and egg from skin, cells and, then create like a hundred or a thousand embryos and test them all and then make, the ones that the. Best even better so, you know it would be no big deal and would be really cheap apparently. So all of that if that thought experiment, it's a thought experiment because it's absolutely not, the case, still. Leaves for me this other question, about. Those. Conditions. About which I could be sure, it. Would be better to not have and those, ones where I, think. It's unclear, so, has. You, know we have a bit of a bad history for. Thinking, that certain, things are diseases. Disabilities. Or differences, that are. Bad. Being. Homosexual, was in the DSM. Psychiatric. Manual, for, a long time and it was considered to just be understood, that it was a disease and it was a bad thing and I don't think that people in the United States necessarily, think that anymore so I do have, this and. I think similarly something, like deafness, or we. Were just talking today about Greta. Her. Last name their, Swedish young Swedish activist with Asperger's, who is his. CV you know that she thinks that her. Condition. Actually, makes. Her a better activist. So, all they want is us, to recognize, that there will be things that we agree are really bad like nobody's, gonna argue that a sex is a great thing that you know you should have and you should just suck it up but, there are lots of disabilities. In the middle where it's very difficult to, say and I.

Think Parents, ultimately should make those choices for themselves but, I want us to, alleviate. Those. Two D burden those decisions, as much as possible so they can really do make a choice that's consistent, with their values so you and I might disagree. About. Maybe. Not really severe autism I don't know but maybe some conditions, on the high-functioning. End, of the spectrum I'm not sure. But. I think that we should be encouraged to think hard about a, decision. Like whether or not that would be the kind of thing where you would want to eat it out and I'm. Concerned, about social, pressure to make the choice in one direction or the other thank. You. Yeah. And I can repeat the question. Species. Centric. Only. For Homo sapiens, in ears boxes, should, we be applying it to Christopher. Technologies. For animals, that we control, and. There's. A sort. Of envisioning, the parental. Aspects. Of those species. And then, thinking about the future as, Homo. Sapiens, maybe start to break apart does. It only stick, with Homo sapiens, and doesn't, stick with the, sort of byproducts. Of genetic, controls that you could create additional. Maybe a homo CRISPR, is soaring as, we see other source. Species, in. So. The question is whether or not my argument only applies to the current version of Homo Sapien or applies. To other animals, or other future, versions, of us. So. I definitely, do. Not. Think. That I or, many people are able to make a, any. Kind of moral argument that transcends. The development, of the human self. I already. Know that the argument I'm making is not, supported, by transhumanists. Who haven't managed to change themselves into a different species but would like to be able to do so and they just don't agree with, me that there might be some limits that people ought to be allowed well I guess they might think it's fine if some people don't want to join into the transhumanist phase, but they think it's misguided right, it's the wrong decision. But. Your, question about other species. Made. Me go, back to something I said at the beginning that, I think, the parenting context is an. Interesting playground. For. Thinking, about some of the same, kinds of questions about control, and acceptance, in the role of humans in the, world in.

Other Contexts right so. Well. Whether we would want. To be similarly. Cautious. About making. Changes, to non-human. Animals. That. Seems to me like a good. And that there might be values. Aside, from safety. And efficacy that, would guide that, work. So. I've done a little bit of thinking about the playing God argument, because that comes up outside, of in reproductive, context but also just like you know with mosquitoes and things like that too. And as I see it in my remarks it's often, considered a quasi-religious. Concern and sort of dismiss is like nonsensical. Or not belonging in public debate or in policy, but I, think, it often codes for something else. We, don't just. By the nature of our society. Western, society, in particular we. Don't have a good language for, moral. Concerns, that doesn't often sound like it's come, during on religion, and then, what. You end up with in is a, sort, of public debate, system that can only tolerate. Arguments. About. You. Know sort of GDP. And. Population. Growth and things that can be measured so that's the by a political, critique right of the current our, current way of thinking and it. Means, that if you say something like I think this is playing guide that people just say you don't know what talking about and it's nothing, to do here where, they might be saying something not about God specifically. But about their, discomfort, with. Being. The ones in, the. World who are the controller's, of it right, that the role feels. If. Not. Like some kind of sacred. Transgression. Just. Like a role that. They. Wish that they don't, want to have right, so not everybody wants. To be responsible. For. The. Lives of a whole variety. Of, new new organisms, or altered organisms. That's. A huge responsibility, and it's a particular way, o

2019-09-28 19:17